The Leopold and Loeb Murder Trial, 90 years later

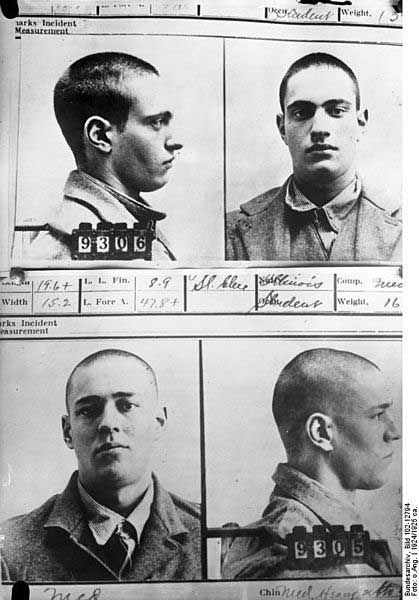

Source: German Federal Archives, Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-00652 / CC-BY-SA

The recent news of a bungled execution has again stirred debate over capital punishment, emotions running high between advocates and opponents of state executions.

So it is interesting that this week marks the 90th anniversary of a horrific crime and a defense that, remarkably, spared the lives of two killers. If any criminals were worthy candidates for execution, they would have been Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb.

In 1924, they pled guilty in a Chicago courtroom for a crime with a shocking motive. The two teenagers—wealthy and highly intelligent—had murdered a fourteen-year-old boy to prove their ability to live beyond traditional ideas of good and evil and to demonstrate their intellectual superiority.

They began with petty crimes in 1923: theft, arson, and vandalism, but then set their sights on committing the perfect crime.

On May 21, 1924, Leopold and Loeb rented a car and drove to a school in the Kenwood area of Chicago, where they would find their intended victim: Robert Franks. Loeb was able to convince the boy to get into the car with them because Franks was his cousin, and he had played tennis at the Loeb house often.

With the boy inside, the car sped off. The moment the car turned the corner, one of the young men—it could never be established whether it was Loeb or Leopold—dragged Franks into the back seat and killed him by repeated blows to the head with a chisel.

The young men wrapped the boy’s body in a robe and drove south to the Illinois/Indiana border. Their destination was Wolf Lake, a stretch of open industrial land beyond the Chicago limits where Leopold had frequently gone bird-watching. There, they dumped the body in a railroad culvert and returned home. That night, Leopold called Bobby Franks’ mother to tell her that her son had been kidnapped. The next day, they mailed a ransom demand, which had been written on a stolen typewriter.

Even before any ransom could be delivered, however, a worker discovered the body of young Franks. Leopold and Loeb decided to abandon the kidnapping, a ruse only intended to distract the police. They destroyed the typewriter and the robe they had used to wrapped the body, and then went on with their lives, convinced that the crime would never be traced back to them.

Leopold simply ignored the outcry in the newspapers, but Loeb couldn’t stay away from the investigation. He followed the police and reporters covering the case, and struck up conversations with them so he could offer some misleading theories about the crime.

While searching the area where the body had been discovered, a detective found a pair of glasses with a unique hinge design. He learned that only three pairs of glasses such as these had been sold in Chicago, one of them to Nathan Leopold. When questioned, Leopold told the police that, as an avid birdwatcher, he often visited the marshes around Wolf Lake, and that he must have dropped the glasses in the marsh on a similar expedition.

Source: German Federal Archives, Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-12794 / CC-BY-SA

The police now treated Leopold and his friend Loeb as suspects. When they were brought in for questioning, both young men claimed they spent the night in the family car, cruising around Chicago, looking for girls. But the Leopold family chauffeur later told police he had been working on the family car all that night.

Confronted with this inconsistency, Leopold broke down and confessed. Loeb soon admitted his guilt as well.

The trial that followed grabbed headlines across the country. Loeb’s family, fearing their son would be executed for the murder, hired Clarence Darrow, the famous defense attorney and well known opponent of capital punishment.

Following Darrow’s orders, the young men pled guilty to the charge, which meant they would be tried without a jury. Darrow believed he could get leniency more easily from the judge than from a jury.

With the question of guilt answered, America’s newspapers now focused on the question of whether or not Leopold and Loeb would hang.

As the trial closed, Darrow summed up his defense before the judge in an argument that ran for 12 hours. He made the usual argument that capital punishment did not prevent other crimes. Murderers simply did not think of being caught and executed at the moment they killed.

He asked the judge to consider the age of the defendants: Leopold was 19 and Loeb, 18. He added that hanging the young men would also mean a life-long sentence of bereavement for their families.

But in his summing up, Darrow addressed the larger issue of public vengeance and disrespect for life. From time to time, he said, a blood hunger had risen up in society. When Americans were consumed with a desire to punish others or defend themselves, they would “place a cheap value on human life.”

He had seen it in 1917, when the country had been consumed with war fever. Young men were encouraged to see killing as a solution. “The tales of death were in their homes, their playgrounds, their schools; they were in the newspapers that they read; it was a part of the common frenzy—what was a life?” he asked. “It was nothing. It was the least sacred thing in existence and these boys were trained to this cruelty.”

After the war, he argued, the homicide rates had risen. A generation had grown inured to killing, often seeing it as a solution to problems.

America, Darrow argued, needed to return to the level of civilization it had enjoyed before it contracted war fever. “More and more fathers and mothers, the humane, the kind and the hopeful… ask that the shedding of blood be stopped, and that the normal feelings of man resume their sway… I am pleading that we overcome cruelty with kindness and hatred with love.”

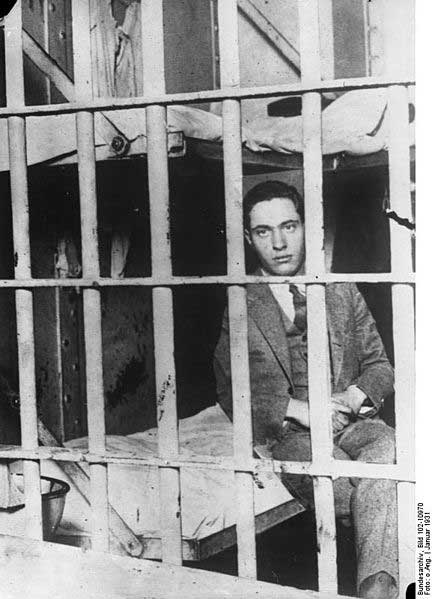

Source: German Federal Archives, Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-10970 / CC-BY-SA

“I know the future is on my side,” Darrow said. “Your Honor stands between the past and the future. You may hang these boys; you may hang them by the neck until they are dead. But in doing it you will turn your face toward the past.”

In the end, the judge sentenced both Leopold and Loeb to life imprisonment plus 99 years for the kidnapping.

It is interesting to note that Darrow did not argue that Leopold or Loeb would reform if spared a death sentence. He knew they were “not fit” to be loose in society. “I believe they will not be, until they pass through the next stage of life, at forty-five or fifty,” he admitted. “Whether they will then, I cannot tell…”

“When life and age have changed their bodies, as they do, and have changed their emotions, as they do—that they may once more return to life. I would be the last person on earth to close the door of hope to any human being that lives, and least of all to my clients. But what have they to look forward to? Nothing.”

Loeb was killed by an inmate after twelve years in prison, but Leopold lived long enough to be paroled and was released in 1958, having serving 33 years. He had kept his sanity by teaching classes for other inmates, learning over two dozen languages, organizing libraries in the prison, and participating in medical research.

Upon his release, he moved to Puerto Rico where he had been hired by the Church of the Brethren. For the remaining 11 years of his life, he worked among the poor as a hospital technician.

He had often been asked in prison if he had reformed. As a Post article reported in 1955, he would reply that he was “quite a different person today. Even physically there is not a cell in my body that was there in 1924.”

Despite all the years that had passed since his vicious crime, he still could not understand or explain his own actions. The Post quoted him as saying,

“I am in no different positions today than I was twenty-nine years ago. I can’t give you a motive that makes sense. It was just a damn-fool stunt done by a child, a child without any judgment. It seems absurd to me today, as it must to you and all other people. I am in no better position today to give you a motive than I was then.”