A Black Champion’s Biggest Fight

The prize fight held on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada was hailed “the Fight of the Century.”

In fact, it was just part of a fight that has been as long as our country’s history.

On that date, African-American champion Jack Johnson was defending his title against Jim Jeffries, as well as defending his race against a racist opponent. His victory detonated America’s first national race riot.

Seven years earlier, Johnson had won the “Colored Heavyweight Championship of the World.” He then achieved what no black athlete had done before: secured a chance to take a championship title from a white athlete. He boxed and defeated Canadian Tommy Burns for the world heavyweight title.

Johnson’s win challenged the racial superiority assumed by many white Americans. Sports writers and white fans called out for a “great white hope,” a heavyweight boxer who would re-assert white supremacy in the ring. When former champion Jim Jeffries agreed to fight Johnson, he publicly said his intention was “to win the title back for the white race.” And “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.”

The need to beat Johnson was made even more urgent because of his personality. He was flamboyant, proud, lived lavishly, drove recklessly, and had affairs with white women. So when he climbed into the ring in Reno, Johnson could sense waves of resentment rising from the crowd of 22,000 spectators. Jeffries even refused to shake his hand before the match.

Jack Johnson vs James J. Jeffries (uploaded to YouTube by Classic Boxing Matches)

Twenty-five years later, in an article from the August 3, 1935, issue of the Post, Jeffries said he trained intensively for a year-and-a-half before the match. He got back into shape and dropped his weight from 285 to 220. But just days before the match, he caught a severe case of dysentery that kept him from putting up his best fight. But there was no talk of illness in the days following the match. Then, Jeffries said, “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in 1,000 years.”

White boxing fans who had made the match a contest of the black and white races felt humiliated and angry. They took the fight from the ring into the streets of American cities.

It was not a good year for race relations in America. At least 67 black Americans were lynched in 1910. The Keokuk, Iowa, newspaper that carried the news of Johnson’s victory also featured a front-page story about the black population of Charleston, MO, fleeing the city after two black men were lynched in the street by a gang of white men.

That same paper reported race riots broke out in 50 American cities following the news of Jeffries’ defeat. In New York, according to the Daily Gate City, 11 different racial brawls were reported on the night of the Fourth. Crowds, the paper reported, tried to burn tenements in black neighborhoods. African Americans were dragged from trolley cars in several locations by white rioters and beaten.

In Columbus, Ohio, white spectators repeatedly set upon 400 black men and women who were marching in a parade celebrating Johnson’s win.

A black man buying a newspaper was accosted by a mob, who demanded he tell them what he thought of the fight. “I am neutral,” the man replied. “Let’s kill the [racial epithet],” someone said and the gang approached him. He pulled a knife and held them off until the police arrived.

One reason for the attacks was the fear that African Americans would abandon the deference they were expected to show for the racial majority. A New York Times editorial written two months before the fight stated, “If the black man wins, thousands and thousands of his ignorant brothers will misinterpret his victory as justifying claims to much more than mere physical equality with their white neighbors.”

For some white fans, this championship bout ruined the sport. Eight years later, a humorous note in the October 6, 1923, Post observed, “The papers have been full of the news of prize fights. There must be some mistake about it. As nearly everybody knows, the boxing game in this country died when Jack Johnson whipped Jim Jeffries. It was repeatedly and authoritatively stated there never would be another prize fight.”

Five years later, Johnson was defeated by Jess Willard, a white boxer. Many white boxing fans were exultant. The book Jess Willard: Heavyweight Champion of the World described the aftermath: A sports writer for the St. Louis Times reported, “thousands and thousands of fight fans as well as thousands and thousands of ordinary citizens flooded the downtown streets waiting for the decision.” When they heard Willard had won, “they acted like crazy people.” According to the New York Tribune, the news prompted “respectable business men [to pound] their unknown neighbors on the back and [caper] about like children.”

In a May 8, 1915 editorial, the Post observed, “Critics seem quite unanimously of opinion that this event… is a thing of high importance to the white race. They seem, also, quite unanimously of opinion that Mr. Johnson would have beaten his white antagonist handily if he had not for some years followed an injudicious and deleterious mode of living. We are puzzled to discover a cause for racial pride in the circumstance that a white man was able to whip a black man only after the latter had impaired his constitution by dissipation.”

Three years before the match with Willard, while he was still champion, Johnson had been arrested and charged with violating the Mann Act for driving his white girlfriend “across state lines for immoral purposes.” Johnson fled the country to escape prosecution, which was why his fight was Willard was held in Havana, Cuba.

For years, the rumor persisted that Johnson threw the match, agreeing to take a fall in return for having the charges dropped. Johnson himself contributed to the stories, insisting that he had pretended to be knocked out as part of a deal with the government to drop its charges against him.

But writing for the Post in the April 4, 1925, issue, former heavyweight champion James J. Corbett said of the Johnson-Willard fight, “I was quite near the ringside and watched Johnson closely, and I am morally certain he would never have gone through twenty-six long rounds had the result been prearranged; he would have chosen an earlier round to flop in.” Agreeing with Corbett, Willard said, “If he was going to throw the fight, I wish he’d done it sooner. It was hotter than hell out there.”

But the rumor never stopped hounding Johnson. In the 1940s, having spent a year in jail for the Mann Act violation, he was reduced to boxing in private events. He then got the idea for another way to raise cash, and went to the editor of the boxing magazine Ring, Nat Fleischer.

Fleischer knew Johnson. He had been at ringside when Johnson fell. According to a March 16, 1946 Post interview with Fleischer, “Johnson went down under big Jess Willard’s blows in the twenty-sixth round, rolled over on his back and raised an arm to shield his eyes from the tropical sun as he was counted out.” The arm-raising incident was cited as proof that Johnson had gone into the tank for Willard. Fleischer, convinced that the bout was fought on its merits, always argued that even a semiconscious man would instinctively try to shield his eyes from the blinding rays of the sun.

Despite Fleischer’s certainty of Johnson’s integrity, the Post reported that, “Johnson came to Fleischer with a signed confession stating that he had ‘gone into the water’ for Willard. Nat paid him $250 for it, after the ex-champion had signed an agreement giving him the exclusive rights to publish the story. Fleischer put the document in his safe, where it has since gathered mildew. Fleischer says Johnson has since tried to buy back the ‘confession,’ because he can get a better price for it elsewhere.”

Nat refused to sell. He didn’t believe a word of it, and chose not to publish the confession to protect a boxer, and a sport, that he revered.

In 2018, 72 years after his death, Johnson finally received a presidential pardon for his violation of the Mann Act.

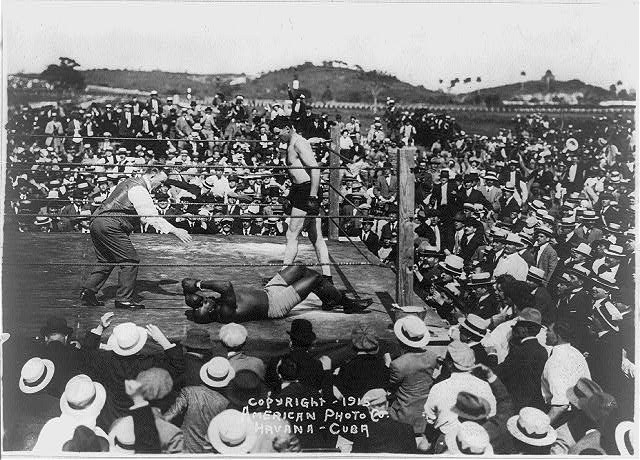

Featured image: Jack Johnson and James Jeffries in 1910 (Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress)