Your Weekly Checkup: Medical Device Malfunction or Degeneration

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

Now that I’ve reached the ripe old age when I can leave my shoes on while traversing airport security screening, the TSA agent always asks before I enter the metal scanner, “Any device implants?” Thankfully, I am able to say no: all my body parts are still original.

According to a recent article, that’s not true for about 32 million Americans (1 in 10) who have at least one medical device implanted. Inserts range from simple items like eye lenses or birth control devices, to complex objects such as cardiac stents, pacemakers, defibrillators, and heart valves.

Creating an implant that can weather the body’s hostile internal environment over a long time period is a major challenge. Manufacturers must replicate the years of toxic impact the body exerts on an implant to be certain the device performs as it should, often for many decades. Even minor changes to a “tried and true” implant can sometimes be disastrous.

Hip implants are a case in point. Degeneration of the hip bone and joint from arthritis or injury can lead to pain, stiffness, and difficulty walking, often requiring total hip replacement. One type of implant is metal-on-metal in which the ball and socket of the device are both made of metal. Walking or running causes the metal components to rub against each other, eventually eroding the surfaces and causing tiny metal pieces to implant in the neighboring tissues. Some of the metal ions can enter the bloodstream to elevate cobalt, nickel, or chromium levels.

Patients often respond to these changes differently. Some experience no symptoms while others have an adverse reaction to the metal debris damaging the soft tissue surrounding the implant; they experience pain, loosening of the implant, and eventual device failure. The changes can impact general health, affecting nerves, heart, kidneys and thyroid. Some companies have recalled specific types of devices. The FDA states that, “All hip implants will need to be replaced eventually, and implant longevity is influenced by a patient’s age, sex, weight, diagnosis, activity level, condition of the surgery, and the type of implant.”

The purpose of this column is to call attention to implants that may not be functioning as optimally as they did after insertion. Patients experiencing new symptoms should not just “tough it out,” but should contact their health care professional promptly for evaluation. The problem may be trivial, requiring a minor adjustment, or significant, requiring device replacement.

If you are that patient, do not put off your checkup.

Do You Really Want to Live to 100?

A man asks his doctor how to live to be 100.

The doctor asked the man, “Do you smoke or drink?”

“No,” he replied. “Never.”

“Do you gamble, drive fast cars, or fool around with women?” inquired the doctor.

“No, I’ve never done any of those things either.”

“Well, then,” said the doctor, “why do you want to live to be 100?”

It was a question that might have occurred to pollster George Gallup as he concluded his 1959 study “The Secrets of a Long Life,” for The Saturday Evening Post. (Read the full story here.) For the report, the Gallup Organization had spent months interviewing 402 Americans from across the country who had all lived 95 years or longer.

When all the data was collected, Gallup drew two surprising conclusions.

First, if you wanted to live to a very ripe old age, it didn’t matter what you ate or drank or how much you exercised.

Second, you’ll live a lot longer if your life is dull.

Nothing helped the human body reach a ripe old age better than an unexciting life of regular habits, little variation, and low stress. The interview subjects weren’t motivated by driving ambitions. They hadn’t even tried to achieve a long life. (Only 9 percent of the group had ever expected to reach their 90s.) “For many,” Gallup wrote, “their only outstanding accomplishment is that they have lived longer than most other humans. … Living to be old is probably the most exciting thing that ever happened to these people.”

They were admirable people, Gallup argued: honest, hardworking, law-abiding citizens and parents. But these elderly men and women had shaped their lives for contentment, not achievement. They were not risk-takers. When the great tide of migration swept westward, they remained where they had been born—usually in a small town.

In their lifetimes, stress wasn’t the buzz word it is today. They might have talked instead of discomfort, worry, nerves—whatever the word used, these subjects had figured out how to avoid it.

“If this still sounds dull,” Gallup concluded, “the chances are that you’ll never make 90.”

Gallup had commenced his research by asking subjects if they could attribute their long lives to any one factor. Fully one-third of the subjects said, “I don’t know.”

Others offered these explanation:

• God’s will (22 percent)

• Adaptability and a good sense of humor (17 percent)

• Hard work (16 percent)

• Good genes—parents or siblings who lived into their 90s (11 percent)

• Keeping regular habits (9 percent)

It shouldn’t surprise you to learn that most of the interview subjects lived lives of moderation—they didn’t eat or drink to excess, and they didn’t smoke. But a significant minority broke these rules.

In 1959, William Perry, 106, of San Francisco had ham and eggs, beans, fried fish, and coffee for breakfast.

Take the issue of drinking, for example. Over half of the people interviewed had never touched liquor in their lives, which might seem like an argument for abstinence. And yet, there was 115-year-old Uncle Charley Washington who, throughout his life, had drank “as much whiskey as he (could) afford.” Also, there was the testimony of 101-year-old Mrs. Marie Renier. For 80 years, she had drunk a quart of whiskey, and in many decades, as much as a gallon of beer a day.

As for food, there’s no consistent answer, either. Some ate lean, others ate richly. Meals tended to be heavy on the starch and protein. If a vegetable made it to their table, it was usually overcooked. Half of them had eaten fried food regularly all their lives.

Overall, there was enough contradiction among the subjects’ answers, aside from the uniform dullness, to rule out any other “secrets” for extending lifespan.

Even adopting a healthy pattern of living—regular hours, healthy diet, regular exercise, etc.—was no guarantee. As Gallup noted, “the only apparent value of their testimony is to give some sort of comfort to those of us who do not conform to the pattern and who covet long life.”

In other words, no matter what rules you lived by, you still had a chance at long life. And if you had followed all the generally accepted rules for good health, you still had no guarantees you’d make it to 100.

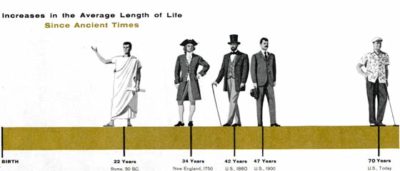

Americans today have a one-in-6,000 chance of living 100 years, which is probably why there are more centenarians living in America than any other country. We of the modern age still believe we can improve our odds with a better diet and more exercise. But if the real secret is living a life that is horribly, painfully dull, would any of us truly want to live to 100?

when the Gallup articles were published in 1959

and 78.5 in 2012.

Rockwell in Hollywood

His scenes of everyday life have become a symbol for Americana at its best, but Norman Rockwell was a portrait artist as well. He painted both sides of the fence politically: Nixon, LBJ, Goldwater, Humphrey, Eisenhower and Kennedy. But we found some portraits of Hollywood names you might enjoy.

The March 2, 1963, cover was of comedian Jack Benny at the ripe old age of (what else?) 39. Rockwell later noted that he was tempted to ask the famous “miser” if he really kept his money in a basement vault.

Rockwell illustrated for other publications as well, such as Country Gentleman magazine, owned by the same publisher as the Post. This magazine’s Summer 1976 issue boasted a Rockwell portrait of John Wayne, whose “rocklike visage challenges the great faces on Mt. Rushmore,” according to the editors, who added, “but he gets around more.”

The May 24, 1930, cover is not exactly a portrait, but the cowboy the makeup artist is working on is none other than Gary Cooper. “He posed for me in Hollywood for three days and worked as conscientiously as any model I ever had,” Rockwell said, “everybody at the lot was crazy about him, and I could see why.”

The fun and mischievous personality of Bob Hope shines through in the February 13, 1954 cover. Hard to believe Hope agreed to pose the very day he returned from a trip to Europe. Most of us would look drained and dull-eyed after an exhausting journey. Can’t you just hear him quipping, “I just flew in from Europe and boy, are my arms tired!”

Norman Rockwell

March 3, 1963

Norman Rockwell

Summer 1976

Norman Rockwell

May 24, 1930

Norman Rockwell

February 13, 1954