Review: Jimmy Carter: Rock and Roll President — Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

Jimmy Carter: Rock and Roll President

⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐

Director: Mary Wharton

Stars: Jimmy Carter, Garth Brooks, Jimmy Buffett, Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Larry Gatlin

In theaters and virtual theater video on demand

Bill Clinton may have been the first U.S. President born after World War II, but as this tuneful, nostalgic documentary reminds us, it was Jimmy Carter who first harnessed the energy of rock and roll to catapult himself to the highest office in the land.

James Earl Carter, born in 1924, went to war to the music of Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey — but he was a Georgia boy whose childhood soundtrack was dominated by the gospel tunes he sang in church and the barn dance music that crackled through the air from the Grand Ole Opry.

By the time he ran for President in 1976, Carter’s musical tastes had already morphed into a love of country-tinged rock and roll, and he brought that sensibility to his campaign.

In fact, if not for his rockabilly roots, the film suggests that Carter might not have become president at all. Director Mary Wharton — a long-time producer/director for PBS’s American Masters series — explores how, in the early days of his campaign, the candidate would come up with desperately needed cash simply by calling on the likes of The Marshall Tucker Band or the Allman Brothers to drop what they were doing to mount a fundraising concert.

“We’d have a concert on Saturday,” a former campaign worker recalls, “and use that money to buy advertising on Wednesday.”

As Carter himself tells Wharton, “It was the Allman Brothers who put me in the White House.”

The film makes clear that Carter was no simple opportunist; his love of music infused every aspect of his life, from the spiritual to the political. Bob Dylan marvels that on their first meeting in the White House, Carter recited many of the songwriter’s lyrics, weaving them into a personal and religious testimony.

“I realized my songs had reached into the establishment world,” Dylan tells the camera. “It made me a little uneasy.”

After his arrival in the White House, Carter filled those historic halls with music of all sorts: giants of classical, rock, gospel, and jazz all took their turns on the stage. One of the film’s most disarming passages involves trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie coaxing the prez, who famously got his start as a peanut farmer, into sort-of singing an awkward rendition of “Hot Peanuts.” Carter hosted the likes of Herbie Hancock, Diana Ross, Dolly Parton, Cher (who drank from her finger bowl) and Willie Nelson (who came to D.C. straight from incarceration after a drug bust in Jamaica).

If music enlivened Carter’s White House years, it also saw him through his darkest hours as president: At the height of the Iran hostage crisis he closed himself into his office and listened to Willie Nelson sing gospel songs.

In the end, the Carter/music connection was not enough to save his presidency. Still, there’s the sense here that it is music that continues to feed his soul — and has helped him become our greatest ex-president.

“I think music is the best proof,” Carter concludes, “that people have (at least) one thing in common, no matter where they live, no matter what language they speak.”

Featured image: Jimmy Carter with Willie Nelson, 1980 (Credit: Courtesy The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

AC/DC Made a Comeback in Black 40 Years Ago

Putting a band together can be an incredibly difficult proposition. The proper chemistry results in combustible creativity, explosive live performances, and a mostly stable mixture of personalities. When all of the elements successfully combine, any change can undo that balance. In that spirit, it’s extremely difficult, but not quite impossible, for a popular band to replace a lead singer for any reason. It’s been done by the likes of Genesis, Black Sabbath, and Van Halen, but it’s also failed for any number of groups. In the case of AC/DC, when lead singer Bon Scott died suddenly in 1980, they faced the daunting prospect of soldiering on with a new vocalist. Not only did the new ingredient fit, it added an accelerant that propelled the band to stratospheric success with one of the best-selling albums in history. 40 years ago this week, AC/DC came Back in Black.

Alex, George, Angus, and Malcolm Young were born in Scotland, and most of the family moved to Australia in 1963. George took up the guitar and joined The Easybeats in 1964, which would become an immensely popular band with an international hit to their credit by 1966. Alex remained in the U.K. and joined the band Grapefruit. Malcolm and Angus, both guitar players, formed their own band in Australia in 1973; from the beginning, Angus wore a costume styled like a schoolboy’s outfit on stage. Their sister Margaret suggested the name AC/DC (which stands for alternating current/direct current) after seeing it on a sewing machine.

“Highway to Hell” with Bon Scott on vocals (Uploaded to YouTube by AC/DC)

The band’s debut album, High Voltage, hit in 1975; the line-up was Malcolm and Angus, with Phil Rudd on drums, Mark Evans on bass, and Bon Scott on lead vocals. Their popularity grew quickly in Australia, and they released a second album, T.N.T., before 1975 was out. The next year, they signed with Atlantic Records for international distribution. In 1977, Mark Evans was fired and Cliff Williams joined on bass (a position he would hold until his 2016 retirement). AC/DC built their American presence through constant touring, opening for U.S. acts like Kiss, Cheap Trick, Aerosmith, and Styx. They also made albums on a steady basis, turning out six by 1979. The sixth, Highway to Hell, finally established them as a chart act in the States; with assured production by Robert John “Mutt” Lange, the record went to #17 and created an indelible anthem with the title track.

Then, disaster struck. Bon Scott died at 33, with the official cause cited as acute alcohol poisoning. The rest of AC/DC considered disbanding, but Scott’s parents urged the band to continue. Much of the next album, Back in Black, had already been written by Malcolm and Angus, and they’d be teaming again with producer Lange. When the time came to find a new vocalist, Lange suggested the former lead singer of the band Geordie, Brian Johnson. In an eerie coincidence, Scott himself had once told the rest of the band about seeing Johnson live and how much he appreciated his style. Johnson came in to audition, and was quickly offered the spot.

“Hells Bells” (Uploaded to YouTube by AC/DC)

Lange, the band, and engineer Tony Platt assembled in the Bahamas to work on the record at Compass Point Studios. With the area bombarded by storms for a few days, Johnson wrote the hurricane-laden lyrics to what would become “Hells Bells.” The band called their management to find a bell that would make the proper sound they wanted on the track; they ended up commissioning a foundry to make a bell to achieve the sound they were after. With the record done, the band went back and forth with the label over the cover. The band wanted an entirely black cover to represent mourning for Scott; they finally agreed to black cover with simple grey lettering.

“You Shook Me All Night Long” (Uploaded to YouTube by AC/DC)

Back in Black hit stores on July 25, 1980. The album was an instant international hit. It went to #1 in the U.K. and #4 in the States; it stuck around the U.S. Top Ten for five months. David Fricke from Rolling Stone praised it highly, writing that record was “not only the best of AC/DC’s six American albums . . . the apex of heavy-metal art: the first LP since Led Zeppelin II that captures all the blood, sweat and arrogance of the genre.” The song line-up included a murderer’s row of anthems. In addition to “Hells Bells” and the title track, stand-outs included “You Shook Me All Night Long,” “Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution,” and “Shoot to Thrill.” “You Shook Me All Night Long” was released as the lead single, and it cracked the Top 40 in the U.S.; to date, the song has sold over three million copies in America; the album sold a reported 25 million copies. While solid numbers remain in dispute due to different certification and ranking systems, multiple sources put the record as firmly in the Top Ten for all-time sales in the States, and behind only Michael Jackson’s Thriller for worldwide sales of a single album.

In the years since, the band has weathered the ups and downs associated with any long-running act. They’ve had tremendous successes like 1990’s The Razor’s Edge album, and the band stayed on the road as a top-selling touring act for decades. In 2003, they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The band also got an ongoing boost from the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The Iron Man 2 soundtrack in 2010 was a compilation of songs from the band, and “Shoot to Thrill” became Iron Man’s theme song across other films, recurring at a crucial moment in 2012’s The Avengers. “Back in Black” also appears in a scene in Spider-Man: Far from Home, wherein Peter Parker humorously misidentifies the band as Led Zeppelin. Unfortunately, Malcolm Young was forced to depart the band in 2014 as he battled dementia; he passed in 2017. In 2016, Brian Johnson was also forced to leave to deal with hearing problems; Guns ‘N’ Roses lead singer Axl Rose joined the band to sing lead on the group’s remaining 2016 dates. At the end of the tour, bassist Cliff Williams retired.

If rock and roll has taught us anything, it’s that no classic band will stay down forever. Rumors have swirled since 2018 that Angus was pulling together songs using guitar tracks that he and Malcolm had laid down prior to his brother’s death. By 2019, rumors had picked up that Angus would be rejoined by Johnson, Rudd, and Williams on a new album and forthcoming tour. If it’s true that one of the most popular bands of all time is about to return to rock, then we salute them.

Featured image: (Quetzalcoatl1 / Shutterstock.com)

Elton John Makes It in America

The history of music can be a tricky thing, especially when it comes to when and how an artist from one country breaks in another country. Some performers, like Canadian country singer Shania Twain, have such stratospheric success that people forget she had an album before The Woman in Me. Def Leppard broke huge in the United States long before they were a hit in their native U.K. And there are a fair amount of people who don’t even know that Rick Springfield is from Australia. In the case of Elton John, he exploded onto the U.S. charts 50 years ago with a self-titled album that Americans assumed was his debut. While his real first album wouldn’t make it to the States for another five years, Elton John cemented the Madman from Across the Water as one of the biggest new stars of the 1970s.

Elton John performing “Your Song” on Top of the Pops (Video uploaded to YouTube by Elton John)

Born Reginald Dwight in England in 1947, he began using the stage name Elton John by 1967; that same year, he began his lifelong songwriting partnership with Bernie Taupin; primarily, Taupin did lyrics and John did melodies. Originally writing for other artists, the duo soon focused on writing for John and put together the songs for Empty Sky, John’s U.K. debut. The most well-known track from the disc is “Skyline Pigeon,” which got U.K. airplay without the benefit of a single release. The next album was lined up to be released in April 1970, but they also secured distribution in the States from Uni Records, then a division of MCA.

Elton John performing “Take Me to the Pilot” (Video uploaded to YouTube by Elton John / UMG (on behalf of Virgin EMI))

Released in the U.S. on April 10, the album’s first single, “Border Song” cracked the Hot 100. John started playing shows in America and opened for acts like Three Dog Night. The band covered John’s “Your Song” from Elton John, but decided not to release it as a single so that John could have a chance with it. That was a stroke of good luck. John had lined up “Take Me to the Pilot” as his next single, with “Your Song” on the B-side, but American DJs started playing “Your Song” more, leading to it being promoted as the A-side. “Your Song” would hit #8 in America and #7 in the U.K. with the album going Gold and earning a Grammy nomination for Album of the Year. As of 2003, Rolling Stone included Elton John in the list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, and the disc is enshrined in the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Elton John and Taron Egerton, who played John in Rocketman, performing in 2019 (Video uploaded to YouTube by Elton John)

As for John himself, he went on to have one of the greatest careers in the history of popular music. He’s sold more than 300 million albums and notched more than 50 hit singles in both the U.K. and the States. “Candle in the Wind 1997,” the rewrite of his original hit in honor of Princess Diana, is the best-selling single in the history of both the U.S. and U.K. charts. An inductee of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, John counts among his other accolades five Grammys, two Oscars, two Golden Globes, and a Tony Award. Queen Elizabeth II knighted him in 1998 for his charity work and contributions to the arts. John plans to retire soon from live performing, though his three-year Farewell Tour has been disrupted as of late due to the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless, John has assembled one of the fondest followings in music. An aggressive advocate and fund-raiser in the battle against AIDS and an inspiration for countless musicians, it’s fair to put down in words how wonderful life is with John in the world.

Featured image: JStone / Shutterstock.com

When Elvis Flopped in Vegas

In a town addicted to building things, blowing them up, and then building them all over again, the New Frontier Hotel in 1955 was a fine example of Las Vegas progress. It was originally built in 1942 and called the Last Frontier, the second resort to open on what would become known as the Las Vegas Strip. Like its predecessor, El Rancho Vegas, the Last Frontier was a luxury resort in old Western garb — “The Early West in Modern Splendor,” as its promotional slogan put it.

But as ever more modern and luxurious hotels opened along the Strip, the Last Frontier decided it was time for an update, and in early 1955 the hotel closed down, gave itself a makeover, and reopened as the New Frontier. The old Western-themed showroom was transformed into the spiffy new thousand-seat Venus Room, with five tiered rows of booths and an expansive stage, “with sides running to such length that the whole thing looks like a gigantic cinemascope screen,” in the words of one awed reporter.

The hotel’s grand reopening in April 1955 was something of a disaster. Mario Lanza, the internationally renowned opera singer and movie star, was booked as the opening headliner, but he suffered a meltdown before the show — an attack of stage fright compounded by drinking — and never set foot onstage. After an hour’s delay, the hotel announced that Lanza had laryngitis, and Jimmy Durante appeared as a last-minute replacement. (Too last-minute for Las Vegas Sun columnist Ralph Pearl, who filed his review early to make his deadline and raved about Lanza’s phantom performance. “Seldom in the history of this town,” he wrote, “has a star done a greater show or received a greater standing ovation.”)

One year later the New Frontier played host to the Las Vegas debut of another, very different performer. He was nervous, too, but he did show up — though many in the audience were probably mystified as to what he was doing there. On April 23, 1956, Elvis Presley came to town.

The 21-year-old rockabilly sensation from Memphis was in the midst of his phenomenal breakthrough year. Elvis Aron Presley recorded his first RCA single, “Heartbreak Hotel,” in January. By April he had the No. 1 record in America; his gyrating TV appearances, on Tommy Dorsey’s variety show and The Milton Berle Show, were the talk of the country; and Paramount Pictures had signed him to a movie contract.

“No check is any good,” said Elvis’s manager Colonel Tom Parker. “They’re testing an atom bomb out there in the desert. What if someone pushed the wrong button?”

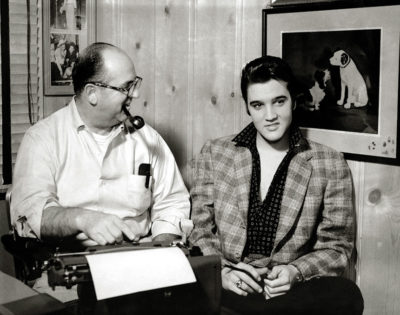

Elvis appearing in Vegas was his manager Colonel Tom Parker’s idea, and not a very good one. Elvis’s frenetic rock ’n’ roll performances, which were causing such a sensation in the rest of the country, were hardly geared for a crowd of middle-aged Vegas showgoers. Yet there he was at the New Frontier, touted as “The Atomic-Powered Singer” (in a town where people could watch real atomic tests taking place in the Nevada desert nearby), the “extra added attraction” on a bill headed by Freddy Martin’s orchestra and comedian Shecky Greene. Elvis got paid $15,000 for the two-week gig, and the Colonel asked for it in cash. “No check is any good,” he said. “They’re testing an atom bomb out there in the desert. What if someone pushed the wrong button?”

The audience at the New Frontier must have thought someone had pushed the wrong button. Freddy Martin, whose “sweet music” orchestra was known for its pop versions of classics like Tchaikovsky’s Concerto in B-flat, opened the show with several of his instrumental hits and a medley of songs from the musical Oklahoma! Next came Shecky Greene, a Chicago-born comedian just gaining notoriety for his raucous Vegas lounge act. Elvis was the closing act. Backed by his three-piece rhythm group — guitarist Scotty Moore, bassist Bill Black, and drummer D.J. Fontana — Elvis performed four songs and was onstage for just 12 minutes. The response was polite at best. One high roller sitting at ringside, according to a witness, got up midway through the show, cried “What is all this yelling and noise?” and fled to the casino. The critics weren’t much kinder. “Elvis Presley, coming in on a wing of advance hoopla, doesn’t hit the mark here,” wrote Bill Willard in Variety. “The loud braying of the tunes which rocketed him to the big time is wearing, and the applause comes back edged with a polite sound. For the teenagers, he’s a whiz; for the average Vegas spender, a fizz.” Newsweek said the young rock ’n’ roller was “like a jug of corn liquor at a champagne party.”

For Elvis and his backup group, accustomed to the pandemonium they were causing in concerts across the country, the response was sobering. “For the first time in months we could hear ourselves when we played out of tune,” said Bill Black. “They weren’t my kind of audience,” Elvis would say later. “It was strictly an adult audience. The first night especially I was absolutely scared stiff.”

Shecky Greene got friendly with Elvis during the run and could see that the kid was out of his element — unable to relate to the audience and lacking the stage experience to win them over. He didn’t even dress right. “He came out in a dirty baseball jacket, just shit,” Greene recalled. “I went to Parker and I said, you can’t let him come out on the stage like that.” The Colonel apparently took Greene’s advice; for the rest of the engagement, Elvis and his band wore neat sport jackets, slacks, and bow ties. But after the first night, they no longer closed the show. Shecky Greene did.

By happy chance, a recording of Elvis’s 1956 Vegas show exists — taped by an audience member on the last night of the two-week engagement. Freddy Martin makes a polite, if rather patronizing, introduction, noting that it’s Elvis’s last performance: “We hate to see him go; he’s a fine young lad and a fine talent.” Elvis opens his set with “Heartbreak Hotel” — slower and bluesier than the recorded version, with Elvis playfully changing the lyric to “Heartburn Motel” in the last verse. His patter with the audience is disarmingly modest; Elvis is acutely aware that he’s a fish out of water. “We’ve got a few little songs we’d like to do for you,” he says at the outset, “in our style of singing — if you want to call it singing.” He alludes to the difficulties he’s been having in the engagement: “It’s really been a pleasure being in Las Vegas. We had a pretty hard time — uh, a pretty good time. …” He makes a few awkward, country-boy jokes, asking the orchestra at one point if they know his next song, “Get Out of the Stables, Grandma, You’re Too Old to Be Horsin’ Around.” After three more numbers — “Long Tall Sally,” “Blue Suede Shoes,” and “Money Honey” — it’s over.

Elvis’s only chance to connect with his real audience came on a special Saturday matinee, scheduled by the hotel expressly for the teenagers who weren’t allowed into the casino for the evening shows. For a $1 admission (the proceeds donated to a local Little League baseball program), the kids got a free soft drink and a chance to shower Elvis with the kind of screaming adulation he was getting almost everywhere but in Las Vegas.

“The carnage was terrific,” reported Bob Johnson in the Memphis Press-Scimitar. “They pushed and shoved to get into the 1,000-seat room and several hundred thwarted youngsters buzzed like angry hornets outside. After the show, bedlam! A laughing, shouting, idolatrous mob swarmed him; he fled to the insufficient sanctuary of his suite. The door wouldn’t hold them out. They got his shirt, shredded it. A triumphant girl seized a button, clutched it as though it were a diamond. A squadron of police had to be called in to clear the area.”

The door wouldn’t hold them out. They got his shirt, shredded it. A triumphant girl seized a button, clutched it as though it were a diamond.

A few of the old-timers in Vegas tried to get hip to the new music phenom. “This cat, Presley, is neat, well gassed and has the heart,” wrote Ed Jameson in a tongue-in-cheek column for the Las Vegas Sun titled “A Cat Talks Back.” “His vocal is real and he has yet to go for an open field. He is hep to the motion of sound with a retort that is tremendous. These squares who like to detract their imagined misvalues can only size a note creeping upstairs after dark. This cat can throw ’em downstairs or even out the window. He has it.”

Though it was a tough engagement for him, Elvis enjoyed Las Vegas. He didn’t gamble much, but he checked out other entertainers in town (among them Johnny Ray, the Four Aces, and Liberace), went to the movies, and rode the bumper cars at the Last Frontier Village next door. He kept company with Judy Spreckels, a sugarcane heiress from Los Angeles, and Vampira, the campy TV horror-show host who was appearing in Liberace’s show at the Riviera. An Elvis fan from Albuquerque, Nancy Kozikowski, was on a vacation in Las Vegas with her parents and ran into Elvis several times during her stay — in the hotel lobby, at the restaurant, and one afternoon when he was wandering alone at the Last Frontier Village. “He recognized me and was very nice,” she recalled. “We took pictures in the 25-cent picture booth together and alone. We also made a very funny talking record together. … Elvis was very nice, very gentle, a perfect gentleman.”

Elvis’s first visit to Las Vegas had one unexpected by-product. Among the lounge acts Elvis went to see was Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, a sextet from Philadelphia that did a kind of slicked-up, finger-snapping, nightclub-friendly version of early rock ’n’ roll. (The group had a bit role in the movie Rock Around the Clock, which had just opened in theaters.) One of the highlights of their show was an up-tempo version of “Hound Dog,” a blues number that had been a hit in 1953 for Willie Mae (“Big Mama”) Thornton. Elvis was so taken with Bell’s performance that he began doing the song in his own act and recorded it later that summer. “Hound Dog” became Elvis’s fastest-selling record yet, and his signature hit.

His 1956 Las Vegas engagement is regarded by most Elvis chroniclers as a rare misstep in a year of meteoric success, otherwise orchestrated to perfection by Colonel Parker, the onetime carny promoter and manager of country star Eddy Arnold who became Elvis’s manager and career guru early that year. The Colonel would later defend the booking, saying it gave Elvis a chance to reach a new audience and pointing out that the New Frontier couldn’t have been too disappointed, since the hotel asked him back for a return engagement.

Shecky Greene — who thought Elvis was a “wonderful kid” but turned down an offer from Colonel Parker to tour with Elvis as his opening act, finding the prospect faintly absurd — never quite understood what all the fuss was about. One day he ran into Bing Crosby, who was in Vegas during Elvis’s engagement. “What is the thing about this kid?” Shecky asked the elder statesman of American pop singing. “He’s a nice kid, but …”

“Shecky,” Bing replied, “he’ll be the biggest star in show business.”

Excerpted from Elvis in Vegas: How the King Reinvented the Las Vegas Show by Richard Zoglin. Copyright © 2019 by Richard Zoglin. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Featured image: ScreenProd / Photononstop / Alamy Stock Photo