Too Old to Be President?

Age has been a big factor in this election.

For the first time, two candidates in their 70s are running for the nation’s highest office. And as you’d expect, both parties are claiming the other’s candidate is feeble, disoriented, and making no sense — i.e., too old for the job.

But 70 years doesn’t mean decrepitude as it once did. “Threescore and ten” years was the lifespan the Bible allotted to a human, but today’s 70-year-olds are different. They’re generally healthier, more active, and less mentally impaired than their parents or grandparents were at that age (if they even reached that age). Can an older candidate be less competent because of age? Certainly. But incompetence can be found in candidates of any age.

Perhaps the concern with age issue is really a concern over health: can a 70-year-old endure the stress that comes with the Oval Office?

The chances are good for either candidate because presidents appear to be unusually hardy.

For example, the Republican Party tried to recruit Dwight Eisenhower to be their presidential candidate in 1948. He turned them down, concluding he would be unelectable. They expected Thomas Dewey — the candidate they chose instead — to serve two terms. Which would make Eisenhower 66 years old if he chose to serve in 1956, and the country wouldn’t want someone that old.

But Eisenhower ran in 1951 and won. Three years later, he had a heart attack, but entered the race again in 1955, and won again. After he left the White House, he continued to play a dominant role in the Republican party until he passed away at 78.

Gerald Ford was 61 when he assumed the presidency upon Nixon’s resignation in 1974. He lived 29 years more. Ronald Reagan, aged 69 years at his 1981 inauguration, served two terms and lived 16 years beyond that. George H.W. Bush was 64 when he entered the Oval Office in 1989. He lived another 29 years.

And of course, there’s Jimmy Carter, who was elected at the tender age of 52. Thirty-nine years later, he’s still with us, building homes for Habitat for Humanity.

It’s significant that, of the six presidents who have celebrated their 90th birthday, four — Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush — served in the past 50 years.

But the number of decades is just one way to consider age. We can also judge a president’s age relative to the average lifespan of his time.

Up to the 1930s, Americans could think themselves lucky if they reached their 65th birthday. But our lifespan has continually lengthened; since 1920, the average American has gained 25 years of life.

Historians have estimated that, in the centuries preceding the 1800s, the average human lived just 35 years. The number is surprisingly low because it is calculated from the ages of all deaths within a year. Nearly half of these deaths (46 percent) were among children under the age of five, which lowered the average age of mortality for adults.

One researcher has concluded that a more realistic average lifespan of a 20-year-old American in 1800 was 47 years — still not a long life. Which is what makes John Adams so exceptional. Adams became president at the age of 61 — fourteen years beyond his expected lifetime. And he lived 25 years beyond his presidency!

Adams’s son, President John Quincy Adams, lived to 80. Thomas Jefferson reached 83, and James Madison saw his 85th birthday.

Today, the average American lives 78.54 years. But an American male who reaches the age of 65, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, has a good chance of living another 19 years.

Which means either candidate might be likely to live to the age of 84 – or beyond.

It’s possible that presidents in their 70s will be looked on more favorably as the proportion of elders in the population increases. By 2060, a quarter of the U.S. population will be over 65 years and old, and the average American lifespan will have risen from 74 to 85 years.

Children today may live to hear candidates someday complain that their 100-year-old opponents are too old to be president.

Featured image: John Adams, Dwight Eisenhower, and Andrew Jackson, three of the older presidents when they assumed office (Adams: National Gallery of Art; Eisenhower: Wikimedia Commons; Jackson: whitehousehistory.org)

When Actors Become Politicians

Today, actor Cynthia Nixon declared that she was running for governor of the state of New York. Celebrities running for – and winning – public office has become practically commonplace. We’ve seen Arnold Schwarzenegger, Al Franken, Jesse Ventura, Clint Eastwood, Sonny Bono, and Donald Trump all win political races.

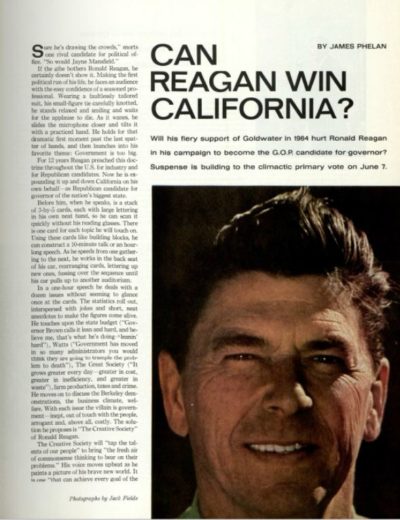

The best known actor-turned-politician was undoubtedly Ronald Reagan. In 1966, he was making his first run for office, as governor of California. The Saturday Evening Post ran a cover story on the handsome and charismatic actor when he was facing off against George Christopher in the Republican primary.

Reagan certainly had his detractors. One former officeholder commented, “He has done nothing but demean the processes of government, without a day of experience.” Three Republican legislators wrote an open letter, begging Reagan to drop out the primary because a win there would surely mean a loss in the general election. Another politician was disdainful of Reagan’s ability to draw crowds, snorting, “So would Jayne Mansfield.”

The primary turned out pretty well for Reagan, as did a few other subsequent elections.

And for those who find the ex-Sex and the City star’s chances for the governorship unlikely, keep in mind Reagan’s response to a reporter who asked him how an actor could run for president: “How can a president not be an actor?”

Allegation Nation: A Brief History of Presidents and Special Prosecutors

With lingering questions about Russian influence in the last U.S. presidential election, some legislators and citizens have called for a special prosecutor. Just how common is the use of a special prosecutor, and when have they been appointed in the past?

The federal government has been using special prosecutors since 1875. In 1978, after Watergate, Congress passed the Ethics in Government Act, which established formal rules for appointing a special prosecutor. Starting in 1983, these investigators were referred to as an independent counsel. The Ethics in Government Act expired in 1999, and the only person who can currently appoint a special prosecutor is the attorney general. Regulations are in place that limit the authority of the attorney general over a special prosecutor, but without a law in place, the enforceability of these regulations in unproven. Congress can’t independently appoint a special prosecutor without first passing a new law allowing them to do so. Before becoming law, the bill must, of course, be signed by the president.

Here’s a table of the men and women who have served as special prosecutor or independent counsel, the issue that each investigated, and the outcome. Special prosecutors have been appointed 29 times. President Clinton leads with 12 separate inquiries; President Reagan is a distant second with six.

History of Special Prosecutors and Independent Counsels

| Year | President | Special Prosecutor / Independent Counsel | Issue | Outcome |

| 1875 | Ulysses Grant | John Henderson | Politicians, whiskey producers, and government employees stealing alcohol tax revenues | There were 110 convictions, $3 million in recovered taxes, and an abiding air of corruption attached to the Grant administration. |

| 1881 | James Garfield | William Cook | Post Office officials taking bribes to award highly lucrative postal delivery routes | The “Star Route” scheme was shut down, but there were few convictions. |

| 1903 | Theodore Roosevelt | Judge Holmes Conrad, Charles Bonaparte | Bribery in the Department of the Post Office | Three hundred post office officials and private contractors were convicted. |

| 1905 | Theodore Roosevelt | Francis Heney | A railroad’s use of fraud to obtain resources on federal land | Over a thousand indictments were issued, but Heney narrowed prosecution to 35 people, including a senator and two congressmen, who all eventually escaped punishment. |

| 1921 | Calvin Coolidge | Atlee Pomerene, Owen Roberts | The sale to corporations of oil held in reserve for the U.S. Navy, most notably at Teapot Dome, WY | Teapot Dome led to the first conviction and imprisonment of a former Cabinet officer. |

| 1952 | Harry Truman | Newbold Morris | Corruption within the IRS | Attorney General Howard McGrath fired Morris. Truman fired McGrath. Over 160 IRS employees were fired. |

| 1973 | Richard Nixon | Archibald Cox | The burglary of the democratic headquarters at the Watergate office complex, and its subsequent cover-up | Nixon, unwilling to cooperate with Cox, ordered AG Elliot Richardson, then Deputy AG William Ruckelshaus, to fire Cox. They resigned instead. Solicitor General Robert Bork stepped in to dismiss Cox. The next year, the House Judiciary Committee filed the first impeachment charge. Nixon resigned two weeks later.

|

| 1978 | Jimmy Carter | Arthur Hill Christy | Accusations that Carter’s chief of staff had used cocaine | No one was indicted. |

| 1980 | Jimmy Carter | Gerald Gallinghouse | Accusations that Carter’s campaign manager had used drugs | No one was indicted. |

| 1981 | Ronald Reagan | Leon Silverman | Organized crime connections of Labor Secretary Ray Donovan | No one was indicted. |

| 1984 | Ronald Reagan | Jacob Stein | Accusations of AG Edwin Meese’s preferential treatment of a defense contractor | No one was indicted, but Meese resigned when Stein’s report was submitted. |

| 1986 | Ronald Reagan | Alexia Morrison | Obstruction of justice by Theodore Olsen, legal counsel to the president | No one was indicted.

|

| 1986 | Ronald Reagan | Lawrence Walsh | Charges that administration officials had secretly sold arms to Iran despite an arms embargo against that country | At least 12 individuals were indicted, including the Secretary of Defense and the National Security Advisor, and many were convicted, but all were pardoned, granted immunity, or given probation. |

| 1987 | Ronald Reagan | James McKay | Charges that former White House aide Lyn Nofziger engaged in improper lobbying after leaving office | No one was indicted. |

| 1987 | Ronald Reagan | James Harper | Charges of income tax evasion by Assistant AG Lawrence Wallace | No one was indicted.

|

| 1990 | George Bush | Arlin Adams | Charges that Samuel Pierce, HUD Secretary, had sold his influence while serving in Reagan’s cabinet | Several of Pierce’s aides were convicted on felony charges of favoritism, but Pierce was never charged.

|

| 1992 | Bill Clinton | Joseph diGenova | Possible illegal search of the passport files of President Clinton by officials of the former Bush administration | No one was indicted. |

| 1993 | Bill Clinton | Kenneth Starr | Accusations that Bill and Hillary Clinton had fired employees of the White House Travel Office to give the jobs to their friends | Neither Bill nor Hillary Clinton were indicted. |

| 1994 | Bill Clinton | Kenneth Starr | Charges of improper behavior by Clinton in the sale of property from the Whitewater Development Corporation | Neither Bill nor Hillary Clinton were indicted, but some of their former business partners were, and 15 of them were convicted. |

| 1994 | Bill Clinton | Donald Smaltz | Charges that Agriculture Secretary Mike Espy had accepted improper gifts | Espy was indicted, but later acquitted, of all 30 criminal charges. |

| 1994 | Bill Clinton | Kenneth Starr, Robert Ray | Death of White House Counsel Vincent W. Foster | No one was indicted. |

| 1995 | Bill Clinton | David Barrett | Charges that Henry Cisneros, Clinton’s HUD Secretary, had lied to the FBI during background checks | Cisneros was indicted on 18 counts of conspiracy and obstructing justice, but later pardoned by Clinton.

|

| 1995 | Bill Clinton | Daniel Pearson | Charges that Commerce Secretary Ron Brown had sold seats on U.S. federal planes on an international trade mission | No one was indicted. |

| 1996 | Bill Clinton | Curt Von Kann | Accusations that Eli Segal, former Clinton chief of staff, had violated conflict of interest rules while fundraising | No one was indicted.

|

| 1996 | Bill Clinton | Kenneth Starr | Charges of improper review of confidential FBI files of members of previous administrations | No one was indicted. |

| 1998 | Bill Clinton | Carol Elder Bruce | Charges that Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt improperly intervened in an American Indian tribe’s application to open a casino | No one was indicted. |

| 1998 | Bill Clinton | Ralph Lancaster | Charges of influence-peddling and solicitation of illegal campaign contributions by Labor Secretary Alexis Herman | No one was indicted. |

| 1998 | Bill Clinton | Kenneth Starr | Charges that Clinton perjured himself when questioned about sexual relations with Monica Lewinsky | Clinton was impeached but later acquitted by the Senate. |

| 2005 | George W. Bush | Patrick Fitzgerald | Suspicions that members of the State Department had leaked the identity of a covert CIA officer for political ends | No one was indicted for the leak, but I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby was convicted on four felony counts of making false statement, perjury, and obstruction of justice. |

Featured image: Shutterstock