Forester in Chief

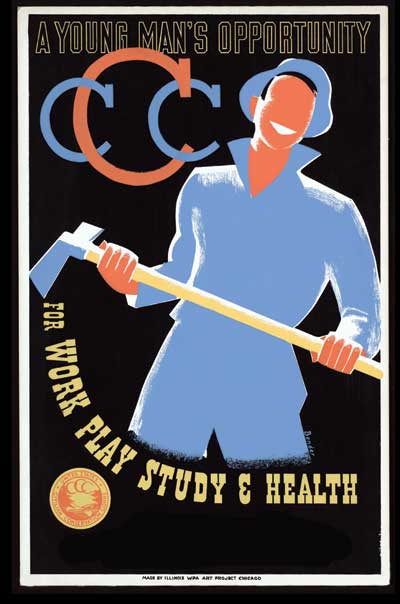

Editor’s note: We remember President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as a leader who took the reins of office in the depths of the Great Depression and, in a record-setting span of nearly four terms in office, steered a course back to prosperity. But few of us are aware just how much we owe FDR for his crusading efforts to save and improve America’s forests. “Think 3 billion trees planted, crucial landscapes saved, from the Okefenokee Swamp to the Olympic Mountains — and more acreage conserved than the size of California,” writes historian Nigel Hamilton.

Growing up in Hyde Park, New York, on a 600-acre family farm, FDR had learned at an early age how to manage land. When his father died while the future president was at Harvard, he took over the farm. “It was the beginning of FDR’s lifelong obsession with trees and the importance of trees to the environment,” Hamilton writes.

Just days after his inauguration, Roosevelt ordered that thousands of trees be planted in Hyde Park, New York.

That FDR, with the crushing weight of the Great Depression on his shoulders, found time for planting trees was tangible proof of his long-held conservationist convictions. “Forests, like people, must be constantly productive,” Roosevelt told the Forestry News Digest. “The problems of the future of both are interlocked. American forestry efforts must be consolidated, and advanced.” To that end he wanted to use forests to ease the economic crisis at hand.

On March 14, 1933, Roosevelt issued a memorandum for the secretaries of war, the interior, labor, and agriculture. “I am asking you to constitute yourselves an informal committee of the Cabinet to coordinate the plans for the proposed Civilian Conservation Corps [CCC]. These plans include the necessity of checking up on all kinds of suggestions that are coming in relating to public works of various kinds. I suggest that the Secretary of the Interior act as a kind of clearing house to digest the suggestions and to discuss them with the other three members of this informal committee.”

FDR convened the first meeting of the quartet of Cabinet members that March. The team was composed of George Dern, from War; Henry A. Wallace, from Agriculture; Harold Ickes, from Interior; and Frances Perkins, from Labor. During the meeting, Roosevelt nonchalantly sketched, on a scrap of paper, a flowchart of the CCC chain of command. As Perkins later explained, Roosevelt “put the dynamite” under his Cabinet members and let them “fumble for their own methods.” Roosevelt envisioned three types of camps: forestry (concentrated in national forest sites); soil (dedicated to combating erosion and implementing other soil conservation measures); and recreational (focused on developing parks and other scenic areas). From the get-go, Ickes was the New Deal’s taskmaster, with the impatience of a drill sergeant. In a symbolic gesture, Ickes ordered the doors to the Interior headquarters locked every morning at 9:01. Showing up late for work, by even a few minutes, meant instant dismissal. Throughout Roosevelt’s first term, Ickes promoted state and national parks with pluck and vigor, rebuffing right-wing senators who claimed the CCC was a Bolshevist threat to democracy.

Frances Perkins — the first female Cabinet officer in U.S. history and one of only two Cabinet secretaries to work for the entirety of Roosevelt’s tenure in the White House (the other being Ickes) — was tasked with coordinating the recruitment and selection of able-bodied CCC enrollees. Initially a quarter of a million unemployed, unmarried “boys” or juniors between ages 18 and 23 (later expanded to 28) were sought. The pool was later widened to include 25,000 veterans of World War I who had fallen on hard times; 25,000 “Local Experienced Men” (LEM) who worked as project leaders in the junior camps; 10,000 Native Americans, who would be assigned to improve reservations; and 5,000 residents of the territories of Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Perkins worried that Roosevelt was biting off more than he could chew. However, as the trees got planted, she soon became a believer.

What made the CCC more than just a dazzling work-relief program was the professional expertise the LEM brought to land reclamation. Skilled young physicians, architects, biologists, teachers, climatologists, and naturalists learned about conservation in a tangible, hands-on way. If not for the Great Depression, these workers would have found themselves engaged in upwardly mobile jobs. But by a twist of fate, as many of their diaries and letters home make clear, these LEM were indoctrinated in New Deal land stewardship principles. Later in life, after World War II, many became environmental warriors, challenging developers who polluted aquifers and unregulated factories that befouled the air.

Courtesy FDR Library

Having developed a working model for the CCC, Roosevelt delivered his plea to launch it with the passage of the Emergency Conservation Work Act, which would provide the authority to create, by statute, a “tree army” to provide employment (plus vocational training) and conserve and develop “the natural resources of the United States.” He sent his bill to Congress on March 21. Roosevelt made it very clear that reforestation projects wouldn’t interfere with “normal employment.” In a message to Congress, Roosevelt stated in part:

I propose to create a Civilian Conservation Corps to be used in simple work, not interfering with normal employment, and confining itself to forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control, and similar projects. …

More important, however, than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual value of such work. The overwhelming majority of unemployed Americans, who are now walking the streets and receiving private or public relief, would infinitely prefer to work. We can take a vast army of these unemployed out into healthful surroundings. We can eliminate to some extent at least the threat that enforced idleness brings to spiritual and moral stability.

Roosevelt did a marvelous job of selling the CCC, answering congressmen’s questions forcefully but politely. At six press conferences, he invoked public works and the CCC. After a round of debate, the 73rd Congress passed S. 598, Public Law No. 5 on March 31, creating the CCC as a temporary emergency work-relief program. Roosevelt’s unstated hope was that what the New Republic called his “tree army” would eventually become a permanent agency.

Roosevelt hired American Federation of Labor leader Robert Fechner as the first director of the CCC. Originally from Chattanooga, Tennessee, Fechner, born in poverty, left school at age 16 and moved to Georgia to become a “candy butcher” on trains. Mild-mannered and collaborative by nature, Fechner was an intrepid labor reformer. Because of his sterling reputation for fairness — as well as his union background — he proved an inspired choice.

By mid-April, the program was coming to life. According to Roosevelt’s estimation, an 11-man CCC crew could, weather permitting, plant 5,000 to 6,000 trees per day. Surrounded by maps of America, the president studied rivers and streams, deserts and forestlands. “I want,” Roosevelt declared, “to personally check the location and scope of the camps.”

Roosevelt’s “tree army” became a legend from the start, and he became a forester-in-chief hero to many conservation groups. As historian David M. Kennedy noted, the public quickly understood that Roosevelt had a “lover’s passion” for trees.

All over America, CCC tent cities popped up like Boy Scout camps; they were soon replaced with rustic barracks. Each company unit of 200 CCC “boys” was a temporary village in itself. All sorts of bylaws, pledges, and rules of engagement were announced. The “CCCers” received three full meals each day and were issued olive-drab uniforms, which included pants, a shirt, gloves, two pairs of underwear, a canteen, and a pair of heavy, steel-toed boots. In time, Roosevelt and Fechner changed the uniform to a spruce-green color for the coat, pants, overseas cap, and mackinaw (the shirt remained olive). “The issuance of a new uniform distinctive from other governmental services will improve the appearance of the corps,” Fechner noted. “It will also aid in building up and maintaining high morale in the camps.”

Unlike the army, there were no guard houses, drills, saluting, or court-martials. But morale was important from 6 a.m. reveille to taps at 10 p.m. At just $30 per month, these young men weren’t going to get rich: $22 to $25 of their pay was mandated to be sent home to their families; what remained was spent at the canteen, on haircuts and snacks, or at the local nickelodeon. Topnotchers were able to boost their salary by becoming technicians. A gag circulated among new enrollees — “Another day, another dollar; a million days, I’ll be a millionaire.”

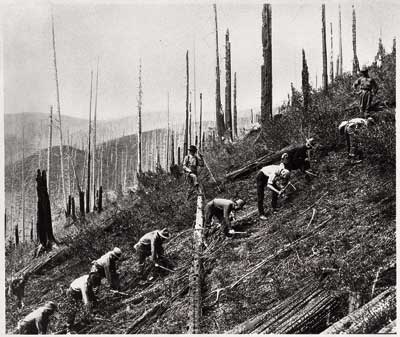

Uniformed enrollees started working at a breakneck pace to plant millions of trees, restore grass, build check dams, practice rodent control and kill invasive or destructive animals, prevent wildfires, and teach bankrupt farmers how to form soil conservation districts. Particularly concerned about California’s forests — which drought and arid conditions had made hyper-vulnerable to fire — Roosevelt instructed CCC crews to cut a 600-mile Ponderosa Way firebreak along the base of the Sierra Nevada in California, the longest such protective barrier in the nation. The CCC “boys” were also dispatched to do immediate battle in the drought-ravaged Great Plains and the soil-stricken American South. Even Puerto Rico had CCC camps, employing 2,400 men.

Roosevelt never meant the CCC to be a panacea for the systemic woes of the Great Depression, but it did save a vast number of young men from homelessness or, even worse, hopelessness. Roosevelt viewed his “boys” not merely as temporary relief workers, but as makers of a permanent, greener new America. Bursting with optimism, he believed the work-relief experience would transform the young recruits intellectually as well as physically. Teamwork and citizenship and conservation would all be learned in the CCC. Only 37 days after Roosevelt took office, the first CCC enrollee — Henry Rich of Virginia — was dispatched to Camp Roosevelt near Luray, Virginia, located in the 649,500-acre George Washington National Forest, the first camp to open. Six additional CCC camps soon followed in Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park, employing nearly a thousand men to thin overcrowded stands, remove dead chestnut trees, plant saplings, install water systems, build overlooks, and lay stone walls. Between 1933 and 1938, owing to New Deal care, state park acreage in America increased by 70 percent. When FDR became president, Virginia had only two state parks. Determined to rectify the recreation crisis, Roosevelt sent 107,000 CCC enrollees into the state, and within three years, six more parks would open.

Courtesy of The National Archives and Records Administration

Although the CCC actually started in Virginia, it was the trans-Mississippi West that the “boys” quickly occupied like an invading army. In the early and mid-1930s, perhaps the most notable CCC infrastructure work in the West was in Colorado, a state ideally suited for a youth corps. Only five states exceeded Colorado’s native forest acreage. Meanwhile, unemployment was at 25 percent. So in the summer of 1933, 29 CCC camps were established.

Many CCC recruits lived in the gateway town of Estes Park and rode red tourist buses (called “woodpeckers” by locals) up to the construction sites. It took six CCC companies, working on a dozen mountain peaks, to help turn FDR’s “Top of the World” road into a 48-mile reality. “A few months ago I was broke,” Charles Bartell Loomis wrote in Liberty magazine in 1934. “At this writing I am sitting on top of the world. Almost literally so, because National Park No. 1 CCC Camp near Estes Park … is 9,000 feet up. Instead of holding down a park bench or pounding the pavements looking for work, today I have work, plenty of good food, and a view of the sort that people pay money to see.”

In the state of New York, enlistment in the CCC began on April 7 and 8 with 1,800 young unemployed men, all carrying welfare agency certificates, showing up at the Army Building at 39 Whitehall Street in lower Manhattan. Cheers and renditions of “Happy Days Are Here Again” were heard. From the Wall Street area, these initial New York City recruits were bused to Fort Slocum in Westchester County, Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, and a segregated African-American CCC camp at Fort Dix in New Jersey.

Roosevelt ordered that half of New York’s 66 CCC camps were to be based in state parks. Four innovative New York CCC camps were erected on private land with the cooperation of the owners. Throughout the Adirondacks were numerous old dams, once installed for logging purposes but now collapsed, leaving flats overrun with sumps and bog vegetation. The CCC, by improving these old dams or building new ones, created nine new lakes.

Pennsylvania boasted the second-highest number of CCC camps of any state, trailing only California. Federally funded historical restoration projects took place at Fort Necessity and Valley Forge. Thirty-seven new fire observation towers were erected in state parks. Ickes, an ardent supporter of the NAACP, dispatched an African-American CCC company (led by black military officers) to landscape and renovate Gettysburg National Military Park with the hope that the experience would foster pride in the unit.

What Roosevelt hoped to do by employing youths, whether rural or urban, was to reduce juvenile delinquency. The New Republic went so far as to editorialize that the CCC was Roosevelt’s way to “prevent the nation’s male youth from becoming semi-criminal hitchhikers.” Education was a key component of the camps. Once the young men were officially enrolled, they would take classes in Forestry, Soil Conservation, and Conservation of Natural Resources. CCCers were further required only to do calisthenics, polish their shoes, brush their teeth clean, and maintain a sense of humor.

From inauguration day forward, Roosevelt ably projected the image of an open-hearted liberal who cared mightily about the downtrodden, struggling families, and the homeless. Increasing the size and scope of the federal government to alleviate suffering blindsided the GOP opposition. The CCC was part of this expansion. The public response was so favorable to the CCC that on October 1, 1933, Roosevelt instituted a second period of enrollment. Three months later, 300,000 CCCers were serving America. In 1935, Congress renewed the program, allowing participation to be over 350,000.

CCCers could initially sign up for only six-month stints. Later they could re-up for a total of 18 months, but after that time expired they had to leave the CCC for six months before they could reenlist.

When CCC acceptance letters arrived by mail or telegram or even word of mouth in Missouri, whoops and celebrations usually occurred. While there is no proper documentation of how precisely the CCC office in St. Louis selected the first 25,000 men from Missouri, a distinctive pattern emerged. Most Missouri CCCers were skinny as a rail, Caucasian, averaging an eighth-grade education, and lacking meaningful work experience. After passing a strict physical evaluation and receiving vaccinations, they were clay ready to be molded.

Within a year, over 4,000 CCCers, directed by the National Park Service, fanned out in 22 CCC camps and worked in 15 Missouri state parks, the majority in the Ozarks. A total of 342 examples of “rustic architecture” erected in these state parks by the CCC have been listed in the National Register of Historic Places as of 2015 — an astounding testimonial to the craftsmanship of the CCCers.

Tainting this fine record of achievement in Missouri, however, was the institutionalization of racial prejudice. Although Roosevelt had originally considered integrating the CCC, the program wasn’t sold to Congress as a civil rights crusade. Nor did he want to offend his Democratic political base in the South — which had been instrumental in his election — by attacking Jim Crow. Early on, the CCC created separate companies for African-American enrollees; 250,000 blacks enrolled in 150 “all-Negro” CCC companies throughout the nation from 1933 to 1942. The president’s uninspired “separate but equal” principle regarding the CCC infuriated civil rights groups.

Each Missouri camp had a company commander, a project superintendent, and an educational adviser. There were also chaplains, doctors, silviculturists (tree experts), agronomists, and engineers. At bugle call, the enrollees made their beds and scrubbed the barracks under the watchful eye of an Army foreman. Because the CCC had certain practices in common with the U.S. Army, it isn’t surprising that many military leaders, after initial skepticism, appreciated the CCC. Reserve officers were often in charge of a camp’s transportation needs, day-to-day management, and operational regulations. Part of the attraction of the CCC for many men was the seductive promise of three meals a day. Once the orange juice was downed and plates of eggs and sausage were consumed, the shovel-ax brigade climbed into the pickup trucks that drove them to work sites. At some sites, CCCers drove giant bulldozers and concrete mixers and wielded hydraulic rock-busters and electric saws. It’s been said that the CCC recruits in Missouri were more likely to stink of gasoline than smell of pine.

Not long after the CCC was established, the mushrooming camps each launched their own newspapers or mimeographed newsletters to chronicle daily life. Roosevelt asked Melvin Ryder — who had served on the staff of Stars and Stripes during World War I — to publish from Washington a nationally distributed weekly newspaper, Happy Days, which would feature propagandistic pieces on life in the CCC camps, sporting events, entertainment, and developments in conservation education. Happy Days sometimes printed entries for the best CCC motto. Many were funny, such as “They Came, They Saw(ed), They Conquered,” or bittersweet: “Farewell to Alms.” The New York Daily News approvingly quoted from Happy Days that the CCC motto was “They’ve Made the Good Earth Better.”

Even though the CCC was dissolved in 1942, the work of the “boys” remains visible from coast to coast. Over the course of its nine-year existence, the CCC conserved more than 118 million acres of national resources throughout America — more acreage than all of California. As the plaque at the School of Conservation in Branchville, New Jersey, reads: “These men participated in the world’s most famous conservation program. America will never be able to repay them. All that is great and good about conservation we owe to the CCC.”

From the Archive

Post Editorials Supported the CCC

The Post’s editorial board generally hewed to a conservative line. But when it came to the CCC, a program many on the right vilified as a socialist initiative, our support was wholehearted.

Better Than Welfare

All manner of schemes have been tried and very large sums have been spent for unemployment relief during the past three years. But no attack upon unemployment yet attempted has in it a greater element of hope and inspiration than the emergency conservation work of the Federal Government. This gives 250,000 men the opportunity of working for six months this summer in the nation’s parks and forests in return for food, clothing, medical attention, shelter and $30 a month, most of which the workers are expected to allot to their families at home.

Great numbers of young men have felt themselves a burden upon their families. Relief efforts in general have been directed to the unemployed married worker with dependents; the unmarried young men have been, until now, largely neglected. The forest camp work is aimed at these youths; its purpose is to redeem them from incipient social rebellion, to raise their depressed morale, to build up their health, to help their families with the allotments sent home, and incidentally to accomplish needed work in the forests and parks.

These young men will put in their six months under wholesome and uplifting conditions. They cannot fail to be better citizens for having spent that length of time in constructive manual labor in forests and parks. Nor can they fail to receive new hope and strength. After all, it is dreary business just to feed people and leave them in idleness. Details may prove thorny, but the idea is definitely promising and the attack upon the problem of idle youth is strategic and direct.

—“Hope for Young Men,” Editorial, June 17, 1933

Self-Respect, Confidence, and Fortitude

How might morality be strengthened in the individual? Above all, by strengthening courage; therefore, proximately, by developing hardiness and health; a fit and ready body is a sturdy prop to self-respect, confidence and fortitude. How admirable it would be if the Civilian Conservation Corps would raise its remuneration, widen its purposes, and draw every American youth for a year into its character-forming discipline, its wholesome friendship with forest, stream and sky!

—“Our Morals,” by Will Durant, January 26, 1935

Some Mistakes Were Made

Recent admissions that political influence has been a factor in selecting part of the CCC personnel are exceedingly distasteful to large numbers of fair-minded and unprejudiced people. … Surely, in the hasty finding of work projects for nearly half a million young men, it is more than likely that some mistakes were made. But the idea of putting hundreds of thousands of otherwise idle youths into wholesome outdoor work amid healthful and often beautiful and inspiring surroundings has appealed to everybody.

—“The Trail of the Politician,” Editorial, September 5, 1936

100 Years Ago: Fear of a Republican Spoiler

Contested conventions, a possible split in the party vote, a self-funded campaign, collaborating opponents, name-calling, border walls, and bathroom rights — many of the controversies that are part and parcel of this year’s presidential campaigns are unprecedented in U.S. history.

Many, but not all. Some of the party politics and controversy of this year’s presidential election echo concerns of the same election a century ago.

In 1916, Democrat Woodrow Wilson was running for reelection with the campaign slogan, “He kept us out of the war,” and his firm neutrality had earned him popular support across the country.

To unseat him, the Republicans nominated Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes, who resigned from the Court to run for office. They hoped Hughes, a moderate progressive, could bring the White House back to the Republicans.

They also hoped Teddy Roosevelt would stay away.

The Republicans had lost the 1912 presidential election when Teddy Roosevelt decided to challenge his former friend William H. Taft for the Republican nomination. Roosevelt was extremely popular, even after spending a term away from the White House. But Taft had worked hard to build support within the Republican Party.

When the Republican establishment gave the nomination to Taft, Roosevelt left the convention and formed his own Progressive Party (unofficially known as the Bull Moose Party). When the votes were tallied, Taft and Roosevelt had split the Republican vote, while the Democrats remained united behind Woodrow Wilson.

Four years later, Republicans worried that the unpredictable Roosevelt would return to divide the Republican vote again.

They needn’t have worried. Roosevelt turned down nomination by his Progressive Party, sending it into disarray. Instead, he came back to the Republican Party and threw his support behind Hughes, bringing many former Bull Moose supporters with him.

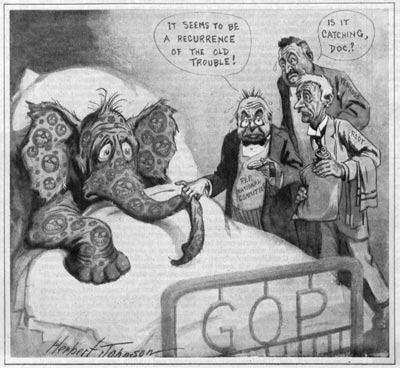

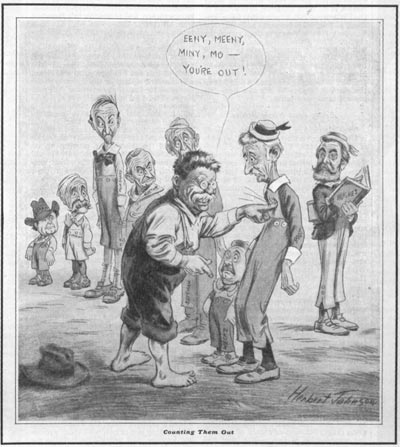

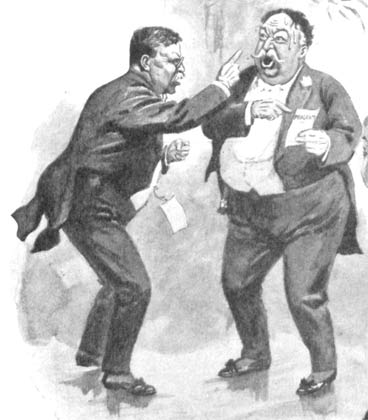

These cartoons reflect Republicans’ political uncertainty before Roosevelt stunned the Progressive Party by turning down its nomination.

February 5, 1916: Early in the election year, Republicans feared a pro-Roosevelt faction among their voters might break out at any moment. The fretful gentlemen with the “Republican National Committee” are Pennsylvania Senator Boies Penrose and New York Senator Elihu Root, who was considered a promising candidate at the time.

February 12, 1916: Imagining Roosevelt would run again, cartoonist Herbert Johnson showed him picking possible running mates. Here, Root has been ruled out, while others await the selection process: Sen. William Borah (ID), Sen. Albert Cummins (IA), Charles Fairbanks (Roosevelt’s former vice president), Paul Morton (former Secretary of the Navy), James Sherman (Taft’s vice president), and Rep. John Weeks (VT). Hughes observes from the sidelines.

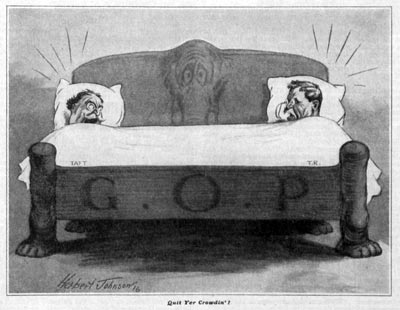

March 3, 1916: The Republican Party’s worst fears realized, though only in cartoon form.

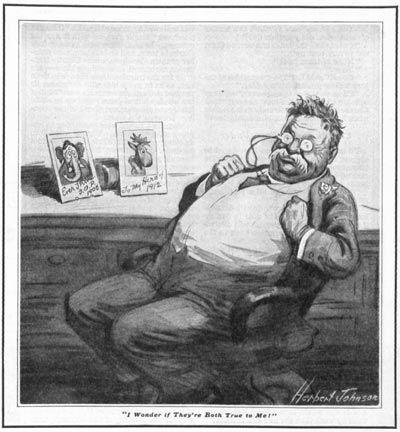

June 3, 1916: Published just before the Progressive Party convention, the cartoon reflects Teddy Roosevelt’s continued support from Republicans. The Republican elephant’s picture is signed, “Ever Thine, 1908,” referencing his presidential victory that year; the Bull Moose in the Progressive’s picture is signed, “To My Hero of 1912,” the year of Roosevelt’s unsuccessful run with that party.

August 12, 1916: By August, Roosevelt had thrown his support behind Hughes but still hadn’t healed his rift with former protégé Taft or his supporters.

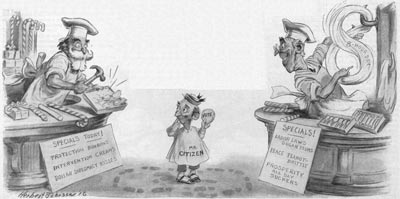

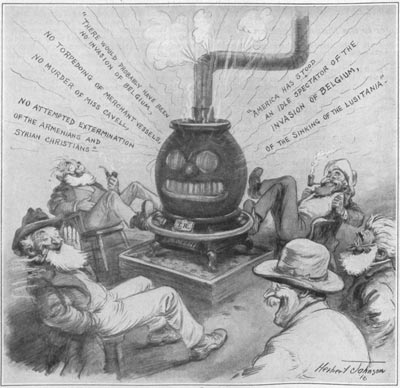

November 4, 1916: Just prior to election day, Johnson showed Hughes and Wilson displaying their wares to voters. Meanwhile, on the opposite page, the old T.R. stove keeps country voters warm with his talk of the need for America to intervene in the war.

Lastly, we include a curiosity from 1916 that presents a rare and informative look at Roosevelt’s record as a successful diplomat. This paid promotion shows Teddy not as a militant imperialist, but as one of the world’s most successful peace brokers.

“Why Roosevelt Would Be Our Best Guarantee of Peace” is highly unusual for several reasons. First, it is one of very few political ads to have appeared in the Post. Second, it is a lengthy (four-page) endorsement of a candidate who had, at this time, expressed no strong interest in running again. Third, it presents Roosevelt, who many considered to be strongly pro-war, as a strong peace candidate.

Only T.R., according to the Roosevelt Non-Partisan League, had the negotiating skills and reputation for fairness that could bring “an early and just settlement of the present European War, as he helped to bring about the termination of the Russo-Japanese War.”

In the end, even though Roosevelt’s return to the Republican Party and abandonment of his Progressive Party largely closed the rift he had cause in the 1912 election, it still was not enough to overshadow Woodrow Wilson’s popularity as the president who kept us out of the European War.

Why Roosevelt Would Be Our Best Guarantee of Peace

An Open Letter to Patriotic Americans

Originally published May 13, 1916

We believe that Theodore Roosevelt as our next President will be our country’s best guarantee of peace with the world.

That belief, based upon the actual character of the man, is absolutely proved by his own deeds when he was President. By the “character of the man,” we don’t mean mere professions. For, in July 1914, all the rulers of Europe that are now in war professed how much they wanted peace. So, professions of peace, unless they are backed up by the deeds that compel peace, are only froth.

By the “character of the man,” we do mean that character which is revealed by an unvarying, straight line of actions. In America, that is all that counts. Lincoln once said, “In lieu of a written platform, a man’s record is his platform.”

Some Obsolete Misconceptions

Theodore Roosevelt’s record for peace has been a sore disappointment to his enemies. Since the beginning of his career, they have predicted, again and again, that he was a “dangerous man who would lead the country into trouble.”

Because of his consistent doctrine that among nations weakness invites aggression, that unpreparedness invites attack, he has been called by his enemies “a menace to peace.”

Thus, when he was nominated for Governor of New York in 1898, three years before he became President, Carl Schurz wrote:

Roosevelt virtually asks us to endorse, by electing him, his kind of militant imperialism which has no bounds. According to him, we need a big navy, “a far larger regular army than we have now,” not for the purpose of keeping order at home, but for action abroad. I would not put him in a position, nor open to him the way to a position, in which he would exercise any influence upon the foreign policy of the Republic; for I candidly believe that he is very dangerously deficient in that patient prudence which is necessary for the peaceful conduct of international affairs.

I cannot support him when his election is generally admitted to be a stepping stone to a place in which his hot impulses and his extreme notions of militant imperialism might do the country more irreparable harm than anything I can think of.

That same year, 1898, The New York Times said, editorially:

Mr. Roosevelt presents himself as a great fighting man, a believer in keeping the flag wherever it has been planted, and in maintaining a big army and navy. … He is presented as a foe of closer relations for peace with our close kin across the sea, and as a man of notable dash.

In the presidential campaign of 1904, Col. Henry Watterson declared:

For the life of me I cannot see how any self-respecting mugwump can vote for Roosevelt. … Parker, the jurist, means peace with all nations, entangling alliances with none. Roosevelt, the warlord, means corruptions at home, complications abroad.

Three years later, in 1907, when Roosevelt sent the battleship fleet on its cruise around the world, the New York Sun said, in an editorial:

We are asked to believe that the expedition to the Pacific is a mere “practice cruise.” He must be a miracle of innocent credulity who believes it. What observant men perceive in this dangerous situation is a cataclysm, trained and bridled for Theodore Roosevelt to bestride and run amuck.

Right here, before going any further, the interesting aftermath of these predictions must be remarked:

Carl Schurz, seven years later, wrote congratulations to Roosevelt on his arrest of the Russo-Japanese War. The Times, after seeing his triumphant presidential record for arbitration, and for the promotion of closer friendship “across the sea,” heartily endorsed his staunchness for peace. The Sun, after longer observation of him, said, “When charged with responsibility, he is as cautious and canny as any doctor of philosophy.”

But the above sayings are samples of the many misconceptions regarding Roosevelt in former years. Many uninformed Americans still cherish them — so persistent is the memory of an old party-cry. These misconceptions are now revived and fostered by enemies who choose to forget the stainless record.

The Record of Facts

But what are the facts? They show a peace record that is 100 percent perfect.

During the seven and one-half years that he was President, he pursued one invariable and consistent foreign policy; a policy of international goodwill and consideration for the rights of others, and at the same time of steady preparedness.

During his seven and a half years in the White House, not an American rifle was fired in war.

Yet, there were no less than seven occasions when a presidential diplomacy just a shade less firm, just a word less friendly, just a thought less wise, might have produced war.

Seven critical occasions they were.

Today we see their full significance, and tremble at what we escaped. But at the time, each affair was handled so astutely by Roosevelt that the danger was scarcely realized outside his Cabinet. Indeed, the very means Roosevelt then employed to escape the danger were bitterly criticized by many who saw nothing of the menace, which, for the sake of peace, he kept out of public discussion.

Here is the record — a peace victory a year, won by astute diplomacy.

Great Britain

The first was with Great Britain. There was a bitter dispute about the boundary of Alaska. After the Klondike boom, the Canadians realized the value of the strip of coast running south. They revived a claimed ambiguity in the original treaty of 1825 between Russia and Great Britain, declaring that that coast should belong to Canada. The claim was absurd. Great Britain offered to arbitrate. Roosevelt refused because our title was so sound, and arbitrators like to compromise.

Here were the makings of trouble. If Roosevelt had let Congress and the press get into the discussion, it is easy to see how public anger would have blazed up, both here and in Great Britain, and the British would have had to humiliate themselves or else fight.

But instead, Roosevelt cleverly gave the British a chance to turn down their own claim and keep their pride. He proposed a Joint Commission, three Americans and three British, thus leaving the matter to the conscientious justice of both parties. At the same time, Roosevelt sent troops to occupy the disputed region.

When in 1903 the Joint Commission gave its decision, the Lord Chief Justice of England, who was one of the British members, had voted with the Americans — the two Canadian members sticking by their claim.

Thus Roosevelt avoided all peril of angry public discussion, with its hot and unforgivable words which would have raised the warlike issue of “national honor.” He averted the mischances of a third-party arbitration. He gave the British a noble chance to inspect and withdraw their claim.

He produced peace, fostered friendship — and kept the Alaskan strip.

Germany

The second occasion was with Germany.

Venezuela had defaulted its payments to German and other European creditors. Under Germany’s leadership, Venezuela was blockaded and a threat was made to bombard its ports and occupy its coast.

Roosevelt was watching, but not waiting too long. He announced our stand on the Monroe Doctrine: “We do not guarantee any state against punishment if it misconducts itself, provided the punishment does not take the form of the acquisition of territory by any non-American power.”

Germany professed she had no such intentions — at least no “permanent acquisition.” She felt free to make a “temporary” acquisition. But Roosevelt knew how temporary acquisitions by European powers soon become permanent. So he asked, through the German Ambassador, Dr. Holleben, the Emperor’s consent to arbitration. It was refused.

Finally, Roosevelt told the German Ambassador that if he didn’t receive the Emperor’s consent in 10 days, he would order Admiral Dewey, then south of Cuba, to take his fleet to Venezuela to prevent a foreign landing.

A week passed. The German Ambassador said no consent had come. He was sure none would come. Roosevelt remarked to him, pleasantly: “Then there’s no use in Dewey’s waiting the full 10 days. If the assurance doesn’t come in 48 hours, Dewey will sail.”

It came (in 36 hours), and Dewey didn’t sail. But the Emperor politely asked Roosevelt to become the arbitrator in the dispute with Venezuela. Roosevelt declined the honor, turning the business over to The Hague Court of Arbitration.

Roosevelt publicly applauded the Emperor’s magnanimity in the cause of peace; and for the sake of good feeling kept sagaciously silent about the inner facts. These were not known to the public till years afterwards when The Life of Secretary Hay was published.

At the time, Roosevelt simply announced to Congress that instead of accepting this courteous invitation to be the arbitrator, he had considered it “an admirable opportunity to advance the practice of a peaceful settlement of disputes between nations, and to secure for The Hague Tribunal a memorable increase of its practical importance.”

It was a masterly escape from war. Another kind of president would have kept sending notes till Germany had occupied and fortified the territory. Then to dislodge her, in defense of our Monroe Doctrine, we would have been in for an aggressive and dubious war. But instead of continuous correspondence, recorded and given to the press, Roosevelt sent one quiet, verbal, and private “Dewey-in-48-hours” ultimatum.

Japan

The third occasion was with Japan.

In 1906, California was ablaze against the Japanese. California excluded the Japanese children from her common schools. California demanded protection against Japanese coolie immigration.

But our treaty with Japan guaranteed these privileges to the Japanese.

Then Roosevelt showed his deepest skill.

In the name of the treaty with Japan, he brought legal suits to restore the school status of the Japanese children. The schools were again opened to them. (He had also quietly increased the Federal garrison in San Francisco.)

For the sake of California, he had informal negotiations with high Japanese officials who, by the way, preferred to keep their coolies at home. These were “conversations between gentlemen,” unpublished, and thus free from misconstruction by the public. The Japanese gracefully agreed not to issue passports for their coolies to come here.

Japanese rights and pride were fully protected. Californian protests were fully regarded. Japan was led to play the part of noblesse oblige, and was justly proud of her own largeness of mind.

The war menace, openly discussed in Japan, melted before our public was awake to it.

Battle Fleet

Yet, just then, lest any foreigners should fancy we were in fear, Roosevelt ordered our entire battle-ship fleet, fully equipped, to sail around the world, incidentally making a friendly call on Japan.

No other nation had ever sent its full fleet on a “round-the-world” cruise. Its physical possibility was doubted. In the press and even in Congress, the order was attacked, and the threat made to withhold funds.

But Roosevelt knew, and he persisted. The fleet was then, thanks to himself, at its highest efficiency. The world saw. Japan saw.

The happy ending of the threatening episode was due to Roosevelt’s fairness of judgment, to his firmness with California, to his adroitness with Japan — and to the big fleet.

Santo Domingo — Cuba — Colombia

Besides these three major occasions, with Great Britain, Germany, and Japan, there were three minor ones, with Santo Domingo, Cuba, and Colombia.

Santo Domingo, in perpetual revolutions, defaulted in her debts, and there was danger of European intervention, as in Venezuela. Roosevelt did an unprecedented thing. He diplomatically led the Santo Domingo Government to request an American official to finance her custom receipts. Roosevelt consented to send an American officer for that purpose who should set aside 55 percent for the debts and 45 percent for the Santo Domingans. Here not a shadow of force was shown, the natives were satisfied, the debts were paid, and Europe was kept off.

Cuba came to a deadlock in her own affairs. President Palma asked for United States forces to help him. But Roosevelt sent one man, Secretary Taft, to advise with the Cubans. When Palma resigned, Taft was there, and the Cubans wanted him to stay. Not till then did Roosevelt send American soldiers, according to the “Platt Amendment” provision, to maintain peace between the factions. As soon as the factions agreed, he withdrew our troops, with never a hostile shot, and the Cubans again realized our justness.

Panama was a case of different color. Colombian troops had sailed to fight the Panama Republic back to submission. But the American warships got there first. The Colombian general was told that fighting would endanger the lives of American citizens who were there, and he was advised to sail back again. Again, not a gun was fired. But Roosevelt was there in time, with wise advice — and with ships.

These celebrated cases are enough to prove Roosevelt’s resoluteness for peace, and his prompt practicality in producing peace.

But two other instances of his foreign diplomacy for peace, the most familiar and famous of all, must be recorded in this review.

“Perdicaris Alive or Raizuli Dead”

When one American citizen, Mr. Perdicaris, had been kidnapped for ransom by the bandit Raizuli in Morocco, Roosevelt had a case which suggests Mexico. The Sultan of Morocco was suspected of being “in with” the fierce rebel bandit. Also, a complicated game of European politics was being played in Morocco. Negotiations brought nothing to pass. Then arrived Roosevelt’s final message, through Secretary Hay, sent to the American Consul (with a war-ship in the harbor) — “Perdicaris alive or Raizuli dead.” Perdicaris was delivered the next day. A startled Europe realized that the United States had a President who was resolute to the minute when even one citizen was attacked.

Russo-Japanese Peace

Roosevelt’s greatest foreign fame rests on his promotion of the Treaty which ended the Russo-Japanese War. The credit fully belongs to him. He perceived the psychological moment for suggesting peace in that awful conflict. As a friend of both Japan and Russia, he plunged in.

He invited the Commissioners of Peace to sit in Portsmouth. When a deadlock arrived in that conference, Roosevelt dared to intrude as the pressing friend, and peace was signed.

The Nobel Peace Prize to Roosevelt

For this achievement he was endowed with the first Nobel Peace Prize, of $40,000 — (which he turned over at once to the Industrial Peace Commission). The whole civilized world warmly concurred in the sentiment expressed in that solemn award, that Roosevelt was the foremost producer of peace of this generation.

Another Peace Tribute to Roosevelt

He received, in 1906, a further foreign tribute, not only for his part in arresting the Russo-Japanese War, but also for his several forceful actions in promoting world peace by arbitration. This tribute meant even more than the Nobel Prize.

It was a spontaneous, volunteered testimonial, signed by 250 of the most powerful men of France. It was a “Recognition of the persistent and decisive initiative he has taken towards gradually substituting friendly and judicial for violent methods in cases of conflict between Nations”; and it declared that “the action of President Roosevelt has realized the most generous hopes to be found in history.”

This French appreciation is made still clearer by the personal tribute of the greatest of European pacifists, the Baron d’Estournelles de Constant, who said at that time:

President Roosevelt has already given four striking lessons to Europe — first, by having brought before the Arbitration Tribunal at The Hague the question between the United States and Mexico over the Pious Fund claims, while Europe was still scoffing at the Peace court it had created; second, in obliging Europe to settle pacifically the Venezuelan affair; third, in proposing a second Peace Conference at The Hague to complete the work of the first; and fourth, in now intervening to put an end to the hecatombs in the Far East.

Our Ablest Man Is Needed For Peace

Do not all these specifications prove, beyond the peradventure of a doubt, that as a resolute Producer of Peace, the practical, straight-seeing, prompt-acting Roosevelt towers above all those professional pacifists that belong to the class whom the Bible condemns for repeating the empty words, “Peace, peace, when there is no peace”?

For Roosevelt believes that “when there is no peace,” a strong, commonsense way must be found quickly to produce peace. He also believes that when a foreign aggressor menaces our peace, it is more surely preserved by a righteous course backed by courage, than by a vacillating course based on safety-first.

The above record, now known to all the world, is the answer to the pessimistic predictions of Roosevelt’s critics quoted at the beginning. The same old pessimism, with a fresh voice, is being uttered now by some other opponents who either are ignorant of Roosevelt’s history or are willfully blinded by prejudice. But history will repeat itself. If Roosevelt becomes President, these new voices, like the old voices, will in their turn applaud.

His attitude on peace and war is rooted in the deepest character of the man. Here is a personal declaration more convincing than idealistic oratory. He said on January 1, 1916:

Foolish people say that I want war. There is probably not in all this country a man who abhors war more and would dread more to see it come upon us. If this Nation should go to war I would go myself, and all my four sons would go, and certainly one and perhaps both of my sons-in-law; and my wife, my daughters, and the wives of my sons would suffer more than the men who went. No father or mother in this audience needs to be told of the sorrow that would be the lot of my wife and myself if we had to see our four sons go to war.

No declaration for peace uttered by any American rings with more manly sincerity. Grant said, “Let us have peace”; Sherman said, “War is hell.” With greater tenderness, Roosevelt utters the same love of peace, the same fearful dread of war. No pacifist has said words that so grip the loving family heart.

Therefore, based on a character that has been proved by deeds:

We believe that Roosevelt’s election as President would be a real guarantee of peace; for the world knows from past experience that he means what he says, and backs his professions of peace.

We believe that the Nations of Europe, remembering Roosevelt’s mighty works for peace, still rely on his fairness; and were he President today, he would be the one man to whom Europe would turn in this awful hour as a trusted counselor.

We believe, further, that if elected President, his unfailing diplomacy, high courage and wisdom, may yet aid in bringing about an early and just settlement of the present European War, as he helped to bring about the termination of the Russo-Japanese War.

We believe, finally, that, if Roosevelt were elected on the 7th of next November, on the following day every Government in the world would begin to shape its course by its abundant knowledge of Roosevelt’s past record in international affairs. But if a new man should be elected on the 7th, immediately all those Governments would say, “Here is another man we do not know; we will wait and try him out for a year or two to see what stuff he has in him.”

We urge all good citizens, of every party, to regard these momentous facts from the broad, patriotic standpoint of the Nation’s future peace, honor, and prosperity. In this crisis, or in any greater crisis that may later arise, America needs her safest man — her strongest man — her greatest man: She needs Theodore Roosevelt.

The article ends with this call for readers to join and donate to the Roosevelt Non-Partisan League.

1912: A Chaotic Presidential Election

Who remembers the men who lost the presidency?

After the winners are announced, the lawn signs yanked up, and life returns to normal, who cares about the politicians who came in second?

Oh, some ex-candidates may linger in the public memory if they make a good concession speech. And some may hang on as the semi-official critic of the new president. Generally, though, the would-be presidents, whose names were once plastered in giant letters across the country—John W. Davis, Alton B. Parker, and James G. Blaine for example—are quickly forgotten.

However, one candidate—William Howard Taft—deserves to be remembered. Not just for his one-term presidency, but because his unsuccessful run for a second term shaped the course of history for America and the world in the 20th century.

The year was 1912. He was the incumbent. However, former President Theodore Roosevelt also wanted to run as the Republican candidate.

Taft won the nomination— he was the sitting president after all. But Roosevelt, not one to be easily deterred from a goal, formed his own Progressive Party. Between them, they split the Republican vote and underdog Democrat Woodrow Wilson would easily win.

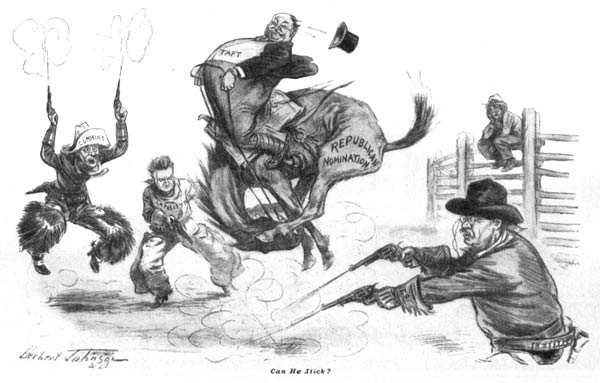

How did things come to such a pass? The field of candidates in the 1912 election was unusually crowded, as shown in this October 1912 Post cartoon (right).

Roosevelt had come to the end of his second term in 1908 with the desire to continue his progressive reforms. So he named Taft, then Secretary of War, as his successor. Roosevelt believed Taft would work just as hard to raise the living standards of American workers, curb the excesses of big business, and set aside land for conservation, public use, and more.

Taft didn’t want the presidency, but Roosevelt could be very persuasive. He was also Taft’s close friend. So Taft agreed to run. He duly won the Republican nomination, and then the 1908 election.

Once elected, though, it was clear that Taft was no Teddy. Where Roosevelt had been passionate and impulsive, ready to push the limits of the law to achieve reforms, Taft was cautious and methodical. Unlike his predecessor, he would compromise with his opponents, and he always worked well within any legal limits on his authority.

Roosevelt soon grew disenchanted with his heir as Taft withdrew support from progressive Republicans in Congress and from several of Roosevelt’s initiatives. The worst offense came in 1910 after Taft put some land marked for conservation back into the hands of private developers. Gifford Pinchot, head of the U.S. Forest Service, publicly criticized Taft’s action. Taft fired Pinchot, who went straight to Roosevelt to complain.

Now Roosevelt was furious. He believed Taft had betrayed him and sold out the Progressive movement. In an interview with the Post (“Why Roosevelt Opposes Taft,” May 4, 1912), Roosevelt explained why he was now opposing his protégé in the race for the Republican nomination.

Mr. Taft was nominated for president … because of his outspoken endorsement of progressive policies. Opposed to these policies … were the Reactionaries. … Without a single exception these men are supporting Mr. Taft today—supporting him openly and with every political trick at their command. They are entirely in accord with his record in the presidency. … Have the Reactionaries become Progressives or has Mr. Taft turned Reactionary? I leave it to the people to judge.

The present Administration has acted for special privilege whenever there was found the slightest authority in law … and has acted for the people in those cases only where it was explicitly commanded by statute. … I gave the people the benefit of the doubt. This Administration has given the benefit of the doubt against the people. [“Why Roosevelt Opposes Taft,” May 4, 1912. Read the full story here.]

It was a dark time for Taft. The man he once considered his best friend—the man who had talked him into running for president—had denounced him and was planning to kick him out of the White House. To make matters worse, Taft knew he had no talent for campaigning. He hadn’t even a glimmer of Roosevelt’s shining charisma. He was a poor public speaker, and he was ridiculously overweight (in the last two years of his presidency his weight had climbed to 345 pounds).

Yet the Republican party leaders wanted him, even if he had no chance of defeating Roosevelt. In a 1912 assessment of “The Republican Situation,” the Post reported that the Republicans would choose Taft despite all odds because the party would rather “face defeat with him rather than disown and discredit him … and themselves.” Assured of the party’s support, and determined to pursue his own style of progressivism, Taft decided to run.

Roosevelt launched his Progressive Party and campaigned hard—even giving a speech after being shot in the chest—and on Election Day, he received 15 percent more votes than Taft. But he was still 2 million votes short of Wilson.

Taft couldn’t have known that his decision to run would put Wilson into the White House at the beginning of a world war. Or that the new president would wait three years before bringing the U.S. into the war. Or that Wilson would be so focused on building a League of Nations, he allowed the Allies to take vengeance on Germany—an action that would ensure another, bigger war would be fought 20 years later. Nor could he know that, by splitting the progressive vote, he ended its power in the Republican party.

But what if Taft hadn’t stayed in the race? Teddy would have surely won. To read what might have happened if Teddy Roosevelt had been elected to a third (nonconsecutive) term, click here.