The Rubik’s Cube Turns (and Turns and Turns) 40

How do you build the perfect puzzle? In the case of one Ernő Rubik, it involved rubber bands, wood, and inspiration. In 1975, he applied for a patent for his “Magic Cube,” but it really broke through when the Ideal Toy Company took it international five years later. Hungary might have known the fiendishly clever device since 1977, but for the rest of the world, this is the day that the Rubik’s Cube turns 40.

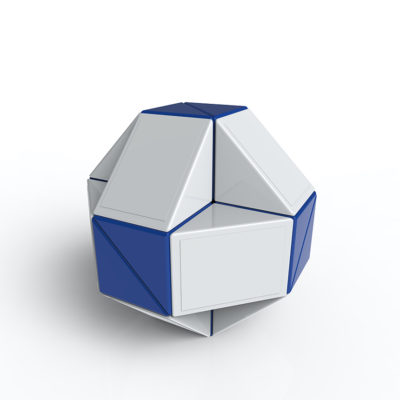

(Babak Mansouri [Public domain])

Rubik’s Cube commericals. (Uploaded to YouTube by Rubik’s)

Businessman Tibor Laczi took the Cube to the Nuremberg Toy Fair in 1979 to try to get the puzzle some attention outside of Hungary. It worked; the Cube caught the eye of Ideal Toys, who acquired the distribution rights and re-named the puzzle the Rubik’s Cube. The toy made its international debut 40 years ago today as it began hitting the Toy Fairs in London, Paris, Nuremberg, and New York. The Cube hit stores in America in May of 1980, and sales took off once TV advertising got behind the toy. 1981 was truly the Year of the Cube; in addition to millions of units being sold in the U.S., no less than three books about solving the Cube were bestsellers. The Cube was also named Toy of the Year in Germany, France, the UK, and the U.S. in 1980, and in Italy, Finland, and Sweden in 1981. One of the side effects of the craze was “speedcubing,” which was simply the practice of solving a Cube really, really fast. It sparked competitions everywhere from college campuses to pop culture conventions.

Rubik went on to create other popular mechanical puzzles, including the Rubik’s Magic and the Rubik’s Snake. With the advent of social media and video sharing platforms, the Cube and similar toys got a renewed boost in popularity; that newfound visibility also prompted the return of speedcubing The inventor himself has spent the last several years touring an exhibition called Beyond Rubik’s Cube, a STEM focused program. Rubik is something of a hero in his home country, having been honored numerous times for his contributions to culture, including the Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Stephen, which is the highest award that a Hungarian citizen can receive.

40 years later, the continued popularity and iconic nature of the Rubik’s Cube speaks volumes about the mind of its creator. It’s a fiendishly simple idea built on interesting principles of mechanics and design. It has both captivated and frustrated millions and maintains a reputation as one of the great toys of all time. No one can say for sure what the perfect puzzle is, but it’s possible that Ernő Rubik came closer than anyone to solving it.

Featured image: dnd_project / Shutterstock