The Vault: Anniversary of a Revolution

In 1917, the Post had correspondents in Moscow and St. Petersburg. At the beginning of the Russian Revolution, Americans hoped it would bring democracy and stability to the nation, but they soon saw their hopes dim for the nation and its people. Here is just a taste of how the Post reported on what it saw happening in Russia.

From “Liberty a la Russe” by William T. Ellis, February 23, 1918:

My sympathy with the revolution is real and unshakable. The peasant has a right to ask patient consideration from the world. In the deepest springs of his being he is after liberty and human rights.

[But] honesty compels the admission that Russian radicalism, up to date, is a failure. From the beginning of the revolution to the present hour, conditions throughout the land have gone from bad to worse. With food abundant in spots, people in other parts of Russia are today starving. While wood in immeasurable quantities is found at short distances from the great cities, people have perished of cold.

From “Despotism by the Dregs” by William Roscoe Thayer, May 4, 1918:

Neither by training nor experience, nor by mental endowment, were [Lenin and Trotsky] sufficiently equipped to run even a dairy; and yet the world beheld them directing the destiny of more than 150 million Russians.

Having wriggled themselves into power, the Bolsheviks bluntly announced that they would rule alone. They would not tolerate representatives of any other class to share in the government, or to speak in either the name of their class or of Russia; and this they called democracy!

Here, Princess Cantacuzene, Countess Speransky — formerly Julia Dent Grant, granddaughter of President Ulysses S. Grant — recalls the Bolsheviks’ rise to power in “The Russian Reign of Terror,” April 26, 1919:

By July 1917, the Bolshevik Party had gathered to itself all the discontented elements in the great cities and all the army’s rebellious spirits, and there was strength behind it enough to frighten [provisional leader] Kerensky and force him to give way.

Step by step they carried out a fixed program. [Russians] of the lower strata, who were so ignorant they could neither read nor write, naturally wanted all those things which were dangled before their blinking eyes, so immediately they fell an easy prey to Bolshevik machinations.

They who had gone through the terrific years of war, who were very needy — in the north, especially — of both fuel and food, believed at once the false prophets who offered them shining gold and provisions, and above all, vodka, of which they had not tasted for three long years. And then beyond all this, the newcomers promised there should be a paradise on Earth.

Anyone who disagreed with the new scheme of life must either flee the country or give way, unless he cared to be shot if noticed. Remaining alive meant making oneself as small as possible on all occasions or paying with one’s life for attracting undue attention.

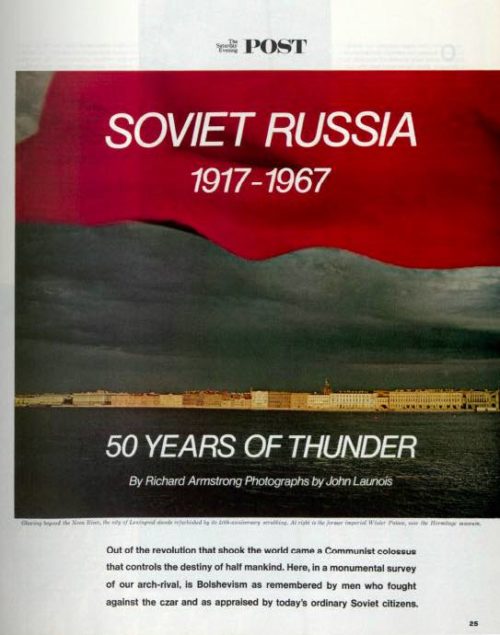

In the decades that followed the Russian Revolution, Post editors criticized the Soviet government for what it saw as its ruthless hold on power, its merciless treatment of Russians, and its export of violent revolution throughout the world. This excerpt from Richard Armstrong’s “Soviet Russia 1917–1967: 50 Years of Thunder,” published on November 4, 1967, is just one example:

On this 50th anniversary, there is a restless stirring in Russia. Not for “Land, Peace, and Bread,” the original Bolshevik slogan. The Russians have that by now. The stirring is for freedom — for freedom of the press most of all. The Soviets, under Khrushchev, took the lid off Soviet society. It is doubtful they will ever get it back on.

An abridged version of this article is featured in the November/December 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.