“The Peculiar Treasure of Kings” by Marjory Stoneman Douglas

Florida journalist and activist Marjory Stoneman Douglas was a fierce advocate for the preservation of the Everglades. In addition to her stories on the environment, Douglas wrote fiction for the Post that won the O. Henry Prize. One such story is “The Peculiar Treasure of Kings,” a yarn about an aged sailor who finds himself on a bark with a captain who is at once a stranger and close family.

Published on November 26, 1927

Whenever old Johnny Mathew had to rest his face from its enforced habit of cheerfulness he came and sat alone on his favorite bench in the little park at Charlotte Amalie, where his mild seaman’s eye could look out over the shimmering translucence of the bay, where the ships lay lightly. Over him and over the statue of some forgotten Danish prince in a cast-iron Prince Albert coat, a flagstaff pushed a bright American flag up into the steady wind from the Caribbean. It was a comfort to let his face sag and his eyes show their weariness that was often very like desperation, here where no one could notice him, among the raw red croton bushes and the tall upcurving coconuts. Today even his shoulders sagged under his worn cotton coat, and his neatly trimmed gray head drooped to his chest. Old Johnny had had a shock. He had seen his son.

He was on that bark out there in the harbor, the bark Mary Parsons, which three days ago, to his excitement, had moved beautifully under her own canvas to an anchorage among the coal steamers, stately as a lady and splendid as new hope. She was that to him. She meant that he might be able to get a berth on her, any sort of job, to escape from this fear he had of being sent back to the States by the authorities, shamefully, as a pauper. The small wad of money he had left after being discharged from the hospital here would not last another month, and his hopes of getting anything to do on any of these casual steamers that stopped for an hour or two were dwindling with it.

He knew steamships well enough. But like the old sailing man that he was, secretly he had a contempt for them — for steamships that battered and reeked their dirty way among the boom and slide of clean oceans which only sails, to his old-fashioned way of thinking, were fit to serve. The Mary Parsons was bound to Rio with lumber, he found out; but off St. Thomas her captain had been taken dangerously ill and she had put in here so that he could be operated on at the hospital while she communicated with her owners. She was waiting now for orders. And John Mathew’s own son, the son that Annie had made him promise never to hunt up or try to know, was the Mary Parsons’ second mate.

He had noticed the boy for the first time yesterday morning, when he had had himself rowed out to the ship to speak to the mate about a berth. The feel of the ship under him, after these sickly months of earth, the orderly lift of her cordage over his head, had made him happy, although the mate had not been encouraging. He was genial enough about it, to be sure, with a surly sense of power already in the swing of his thick shoulders and his thick hands, and old Johnny had lingered to promote the general friendliness with one or two of those sprightly yarns he carried under his tongue, which often won him dinners from the men from the ships.

The mate, with the command of the Mary Parsons so nearly in his grasp, was ripe for friendliness. Old Johnny was a seaman and no beach comber, he could feel him thinking. As a result, old Johnny spoke as an expert of the chicken at Yellow Charlie’s and of Yellow Charlie’s admirable habit of slipping a little very old Jamaica rum to the elbow of anyone he knew was right. That fixed everything. The mate promptly wanted to be shown.

So old Johnny had started for the ladder, feeling fairly cheery and looking thoroughly sprightly, when he saw the second mate. The thing that startled him was nothing he could put his finger on. It was just a whiff of something familiar in the look of that lean brown youth coming silently down the deck, with a still gray eye and a shut look to his mouth, as if something hot and dogged in him pulled tight at his lips, which might have been more restless than he cared to show. The older, smaller man stood for a moment at the ladder top, caught by that look of something that he had known. The second passed him with a cool glance full in the eye, not bold so much as measuring, and the image of him stuck in old Johnny’s mind in spite of his deeper concern.

He met the mate at the boat landing as the dark slid down the mountainside, and he saw that the second had come along in the boat too. Old Johnny talked easily as he led them up the cobbles, under the wooden galleries, past open doors and windows where lamplight splashed across the murmurous dark. They climbed among the heavy scent of jasmine and frangipani, and the tropic night hummed like Africa below the firm sound of their boots. Old Johnny hardly noticed what his tongue was saying because of the way his disturbed mind darted about the silent young figure at his shoulder. What was it about the boy?

Then over a table with the lamp on it, in the bare second-floor room at Yellow Charlie’s, with the night wind bulging the flowered cotton curtain and the sound of feet shuffling by on the stones below, he had heard the mate say, “Mat Brandon here’s our second, Mr. Mathew. I don’t know’s I told you.” And in the moment in which the boy had stretched a hand, silently, to his, he had seen that scar in the left eyebrow.

It was only a thin white line that cut it sharply in two and went up the forehead an inch — an old scar, almost unnoticeable. But at the sight of that, old Johnny’s body shivered with an unforgotten chill. He had caused that scar himself. It was a memory that turned him sick, even now, in his bed nights. The baby had slipped through his fingers as he held him high one time he had come home a little drunk. He remembered how he had been snatched from a jovial mist by the sight of the little thing bleeding where his forehead had struck the edge of a table. Nothing of anything that he had done, all his life, had been so bitter, so remorseful, so remorseless, as memory of that. His forehead was wet now, suddenly thinking of it.

It was his son, right enough — Mathew Brandon; a son a man could cotton to who had that empty place in him for something to be proud of. When a man’s given up his house and his family, and the place where he grew up and the right to his memories and his name, he has that empty place in him. John Mathew, who had been John Mathew Brandon, thought of that, looking at that scar. Then he rapped on the table smartly to let Yellow Charlie know he had brought him some more customers.

The mate found the chicken good and the old Jamaica rum much to his liking, and his red face turned a slow purple as old Johnny, who did not let himself drink much, kept up the talk that seemed always to be expected of him. The second mate, that young Mat Brandon, who from across the table grew to look more and more like his own grandfather but for the mouth and chin that were his mother’s, did not drink much either. Old Johnny could not decide what that chin on the boy might mean. But he did see that he was like his mother in one thing. Under that quiet he was high-strung. The stillness of his body was almost rigidity. His nerves were tight as fiddle strings under a waiting restraint.

The mate was drinking heavily and boasting now — boasting about the captain’s illness and his own chance at the command. Drunk, he was a sloppy brute. Old Johnny saw that he would be blind drunk and helpless in another fifteen minutes. There was no use in his staying. He said so to Mat Brandon, who nodded carelessly, his gray eyes intent, dark in his waiting face.

Old Johnny’s knees were a little shaky, going slowly down the twisty cobbled street, in the soft vast and blackness of the night. He had a clean bare room in an old Danish house and he was glad to get there, worn out with all this unexpectedness. But the important thing was still that he should get away on that ship. If the captain did die, there would have to be changes. He wouldn’t like that mate for captain, but that was not the point. And whatever promises he had made Annie about not ever seeing the son, whom she considered he had disgraced by his drinking, his lightness, his habit of slipping off to sea without her permission, his being undependable and uproarious, had nothing to do with his own necessity now. Poor Annie. She was such a hard-working, righteous woman. She had that dreadful habit of denying to a man even his last scant measure of self-respect.

He was thinking about that still, sitting on the bench among the crotons, staring out at the bark Mary Parsons, full in the diamond radiance of the light. Or rather, he was not so much thinking about his self-respect as feeling it there in him, the very center of himself. He had been uproarious and undependable, as Annie had said. He had got drunk and wasted money and had disreputable friends. He had had a habit of letting responsibility slip out of his grasp, and the morning sea with the sun on it and men’s laughter and the moving sails of ships had set a wild gayety burning in him — burning in his veins with the conviction that life was nothing to get so solemn about. Even now that he was nearly old, he felt that way still, often, all by himself in the sunshine.

But nobody would give command of a ship to a small man and a laugher. He knew he worked better for someone else. As a mate he wasn’t bad. He could handle men well enough. He could stow a cargo cunningly to favor the nature of the ship. It had been Annie’s chief complaint against him that he had no ambition, no drive — that he was soft.

Well, he had certainly been soft to promise what she wanted of him, to give up the house to her, and his name — and the boy. But on the other hand, it was the least he could do for her if she felt like that. What difference did it make? He knew that in this world he was too proud to explain himself or ask favors or hoard bitterness for things long done. Maybe men did not succeed like that. But any other was simply not the way he thought, that was all.

Abruptly now he looked up and saw his son striding intently along one of the paths, even as he was thinking about him. He walked frowning at the ground. A good tall boy, old Johnny thought with a throb of pleasure, broad-shouldered for all his slenderness. He wished that he knew what the thoughts were behind the narrowed eyes, and what the tight mouth would become in an emergency.

As he looked the other saw him and strode up. “There you are,” he said quickly. “I was just wondering how I could get a hold of you. We’ll need you on the Mary Parsons. Captain Caddogan died this morning — and the mate’s disappeared. He was so drunk I had to leave him there. I cabled the owners and they told me to take the ship out at once, as captain.”

The older man stared up at the narrowed gray eyes, a little darker than his own, which looked down at him unwinkingly. There was a fixity about the boy’s face, as if he was more excited, secretly, than he would let appear. What he said had so surprised old Johnny that he stared up, unwinking, too, with something of that same fixity. It was as if the boy shared some secret knowledge with him, but for the life of him old Johnny did not know what that could be. All he could say was, “You’re — captain?”

“I’ve had my master’s papers for a year,” the other said firmly. “The owners knew that. They knew I was looking to better myself if the chance came. The mate should have known, the thick fool. They want the captain’s body shipped back to his wife. So we’re taking the ship out at five this afternoon.”

“You’ve got a berth for me on her?” old Johnny said slowly, to be certain, in all this welter of thoughts.

“That’s what I’m telling you — first mate,” young Mat said impatiently. “It’s a good thing for you and it’s not a bad thing for me to find you here. The papers are ready to be signed at the port office, as soon as you can, Mr. — er — I forget — ”

“Mathew,” old Johnny said, with his jaw out and his eyes bright — “John Mathew. I can be ready in half an hour.”

“Then get aboard as soon as you can, Mr. Mathew,” his son said, and turned on his heel. “We’ve lost time enough as it is.”

That was how John Mathew came to be standing at last by the lee rail of the Mary Parsons in the late afternoon, with the water of the open sea growing indigo ahead. The ship moved leisurely as she came out from between the sun-scorched headlands of the harbor, with the tug beside her, out until her spread sails, saffron with sunset, filled with the plumping steady force of the trades.

The new captain stood by the weather rail, casting his intent gray glance aloft with the swelling canvas and forward to the sea roughening to sapphire beyond the lifting bowsprit. Old Johnny observed him so, and the men forward who had brought the anchor up smartly under the ring of his own voice, lusty with old power and new relief, and were now coiling down the ropes for running — observed the whole ship with a heart so light it was positively giddy. He told himself that a man escaped from hanging could feel no more thankful than he did. It ran from his warmed heart over his elderly, wiry body, down to his heels, like the stirrings of youth.

With the work of getting the ship clear of the land well done, he could pause for a minute, like this, standing silently by the lee rail, to feel that foolish young jig and giggle in his breast. He dared swear to himself at that moment that he felt gayer and lighter-hearted than that surprising son of his, looking solemn over by the weather rail.

Now that he had time to think of this, free of anxiety, the situation was ridiculous. It tickled that easy sense of the ridiculous in him, the light ability for laughter, which poor Annie had found so hateful. He had to call his own son “Sir” whom he’d seen in diapers. It was good as a circus, when you came to think of it. Maybe about the hardest thing he’d have to do would be to keep his face straight.

And to think, besides, that he had never once had a smell at a command, not once in his life, and this young whippersnapper had calmly walked up and had one tossed in his hat. But then, of course, young bub there had probably his mother’s gift of wanting things fiercely. That was one good way of getting them, if you happen to want them. Old John admitted to himself cheerfully that he was not made that way. A first mate’s berth now, with somebody to take the worst of the responsibility, a good ship like this one under his heels, a crew like that one forward that the other first mate had put the fear of God into, and that wasn’t so bad, as crews went — well, he wouldn’t ask much more than that. And it was decidedly something interesting — more than interesting — that his son was captain here. It gave him a feeling — he hardly knew what it was, except that it was pleasurable. Poor Annie! How she would hate it if she knew he was here, like this, with the heels of his heart jigging and life once more running warmly in his veins.

The ship listed slightly and surged forward, having left all sounds of land behind her and filling her decks with the pleasantly prophetic murmur of full sails and taut cordage and a long wake curving and whitening behind to the already half-forgotten purple bulk of St. Thomas. Old Johnny gave no more than that one backward glance of his eye along the wake at those months of desperation behind him. It was not his way to clutter up his mind with old worries. He was more absorbed in the joy of his deliverance, which grew lustier with every blue wave that went under the forefoot, as if now for the first time he could see how he had snatched his very heel out of the sprung trap of poverty and sickness and old age. It might close on him yet, later. But it had not got him this time, by ginger, and it would be a long time before it had another chance!

The young captain walked his place on the deck and the elderly mate walked his, with their eyes occasionally up and always forward and their faces showing no more than the firm sound of their own boot heels on the planks what thoughts were turning and turning in their heads. Old Johnny went below presently to his supper, on the table that was like so many ship’s tables, under the skylight that was like so many that he had known, and he was served by a steward who might have been any one from a number of ships he could remember, looking back down the long alley of his years. The steward, more specifically, was Greek, with a flabby fat face smudged with a shaven beard like charcoal dust on his jowls, and flabby fat hands. The food was nothing to boast of, but old Johnny would not have it changed for Yellow Charlie’s finest chicken, for anything in the world. He slept heavily later, in the berth that had belonged to the red-faced mate, heavy as a runner exhausted with victory.

He woke easily, as his habit was, to take his watch at midnight, and went on deck lively as a cricket. Yet now that he had slept on his happiness and his sense of escape, he found his thoughts moving, as they had in their sleep, with a kind of deep concern about the figure of his son. On deck, the night was soft and huge and quiet, with the ship moving like a lighted shadow below the great shadows that were sails against the stars, and he could speak quietly to the man at the helm and see to the course and recognize with a quick glance the set of the sails and the quiet figures of his watch forward, even while his deeper thoughts went on.

It was certainly strange to think of having a son, a grown son, a son who followed the water and was the captain of a ship at his age — twenty-four, was it, or twenty-five? It was strange to have a human being near him linked by the cobweb ties of old memories, pain and dreariness and forgotten gleams of delight. It was not so much the thoughts of the past disturbed him, walking slowly and observantly by the weather rail, as that he found himself absorbed, more deeply than he had ever remembered being, in a sort of concern about his son. It was like a slow insatiable curiosity.

What sort of man was he? — that was the whole question. What things did he have in him, in the tough woven fiber of his own individuality, that he had had from his father or from his mother? What was there of his own, besides the unknown fusion of his grandfathers and his great-grandfathers? Would he, in a temper, go screaming mad the way his mother did, or like his Great-uncle Joshua on the Brandon side, who used to get sick to his stomach when he fought? Would he stand up to things and endure them without a word, like his grandfather on his mother’s side, or would he give way under the stress of sober burdens, like his own father?

Old Johnny brought himself up against the rail with the force of that. No, by ginger, he wouldn’t want his son to be the sort of man he was! No! No, by heaven! He saw himself at that moment too clearly. He was what he was, and he would stand for anything that came to him as a result of it — stand and not murmur and not regret. But he did not want his son to be like him. There would be no pride for him in learning that his son was like him. But if he were better, if he could prove himself better, better able to meet life on its own terms, more complete, more master of himself, more of a — well, of a man — ah, there would be pride for you!

Old Johnny threw his head back, and his shoulders, as a little shudder of revelation struck him, thinking what it would be like to be as proud as that. If what Annie was, that difficult, righteous, high-strung woman, and what he was could fuse somehow into the body and being of this son so that he could be a new being, made of them both and of all their shadowy trails of forbears, but a better one than either — great jumping Jupiter Amon, old Johnny saw blindingly, that would be — why, that would be — along with food and work to do that you could do, on a good ship — well, that would be about all a man could ask for!

It was a damn sight more than he had ever thought to ask for, he told himself soberly, watching the stars wheel and giving an ear to the creak of cordage and the rushing sound of water under the driven bows, slow deep rollers foaming along timber, that answered to the same deep chord in him who had heard it so almost all the years of his life.

When the new second mate of the Mary Parsons, who had been the boatswain, a Swede, a thin chap with a long bony head and knobby hard hands, awkward on the end of stringy arms, came up to relieve him, with the light from the binnacle flashing up on his long gold eyeteeth and his tow-colored eyebrows as he glanced down to read the card, old Johnny went below to his berth, sobered with the weight of so much thinking. The last thing he thought of, rolling over in his bunk, was that he hoped to God he wasn’t going to turn sentimental. At his age that would be hard to bear.

The dazzling morning brightness splashed through the open skylight on the cups and plates that the steward was laying for breakfast. Old Johnny glanced up through the opening at the piled white of the canvas and at the compass swinging over the captain’s place, assuring himself that nothing much of importance about the ship had been changed while he slept. The wind was holding well. The young captain dropped down the stairs from the after deck, where he had been having a look around for an hour or two, in his pajamas and nodded at his first mate, standing quietly by his chair.

“Fine morning, sir,” old Johnny said, repressing violently the muscle in the corner of his mouth that would twitch. “I see the wind’s holding.”

“Good wind, all right,” his son replied absently, sitting down. “Hey, steward, what’s the idea? The bacon’s burned and my knife’s not clean. Is that coffee hot, Mr. Mate? No, I thought not. Take back this dishwater, steward, and tell the cook to pull himself together. Perhaps you both think you can get by with this as you did when the other captain was sick. I’m giving you fair warning now. I’m not going to have anything dirty or slovenly on my ship. If you can’t scour the knives, there’s plenty men forrard who’d be glad of your place. I want this whole place swept up and the finger marks washed off the door paint. At eleven I shall inspect your pantry and you can warn the cook I shall look into the galley. Send the carpenter aft and have him fix that loose hinge on my door. Snap into it now!” His mouth shut and he sugared his oatmeal deliberately, and old Johnny dipped into his, still checking his wild desire to laugh.

That was Annie’s very housecleaning eye the boy had on him. She used to be death on finger marks on the door paint. But it was a good thing in a ship captain. No sense to letting things go slovenly. That red-faced mate, who had thought himself so sure of this command, would hardly have noticed if the knives had never been washed.

What had happened to that mate, by the way, old Johnny thought suddenly, as the subdued steward brought him a smoking cup of coffee. Drunk and disappeared! What did the boy mean by “disappeared?” Surely he couldn’t mean done away with! Old Johnny glanced slowly at the young captain silently inspecting the new platter of bacon, and studied that tight mouth and that jaw. Was it a jaw that would not stop at anything when there was something he wanted?

Old Johnny had hardly thought of that before because he had had so much else to think of. Men had got drunk and men had disappeared, to his knowledge, before this. But he had seen this boy’s face that night, watching the red-faced man turn swinish and sodden, and the memory of that look on it — that intent, high-strung, very nearly dangerous look — struck him now with a light chill. There was the same face at the head of the table, still intent, still silent, but now it had a ruddy color under the brown, and the mouth had smiled at him.

The boy was wearing the first day of his command with an unmistakable joyousness under the restraint of his position. Yet what had he done to bring him to it? It troubled old Johnny more than he liked to confess. Was he growing squeamish as well as sentimental in his old age? What difference did it make to him? He was here, wasn’t he?

It was pleasant to be on deck in the broad brilliance of the morning, with the ship racing forward splendidly over a sea of ridged and dazzling indigo. The intent face of the captain was there by the weather rail. And presently he was ordering more sail crowded on. Old Johnny snapped with vigor into his work, letting his head blow clear of thoughts. The jib boom thrashed steadily at the southward horizon. The deck bustled.

When the work of spreading the additional canvas was done the captain ordered the standing rigging overhauled, replaced and repaired, and told old Johnny privately that if that didn’t keep the men busy enough he could have out the chipping hammers and get at the cable. Old Johnny saw that there was something working at the boy behind his tight mouth and his narrowed eyes — something that drove him as he was driving the men and the ship.

Well, that was all right, the mate thought mildly, getting into the stride of his job. The boy seemed to know his stuff. He had ambition. If it was work he wanted old Johnny could supply it for him. It was good to get at it again after all these months. In no time at all he had the decks humming with orderly activity. The men weren’t a bad sort. He let them have a joke or two now and then along with orders and liked the way they took to it. He was getting to know the members of the crew as individuals, recognizing an old hand and a good worker here and there, recognizing which ones would shirk in a pinch and which ones could be depended on.

There was a little red-headed feller in his own watch who made him laugh, he was so like a monkey. Restless like a monkey and always on the grin. But a smart hand, none better. He knew well that what often seemed like freshness and impudence from a man like this was only a kind of nervous energy. Give a feller like that a pace to set the others and he’d have them all looking lively. That kind would work harder on a joke at the right minute than for a dozen belaying pins ready up the sleeve. Not that old Johnny wouldn’t be there with a blackjack anytime he had to. But he never liked that way.

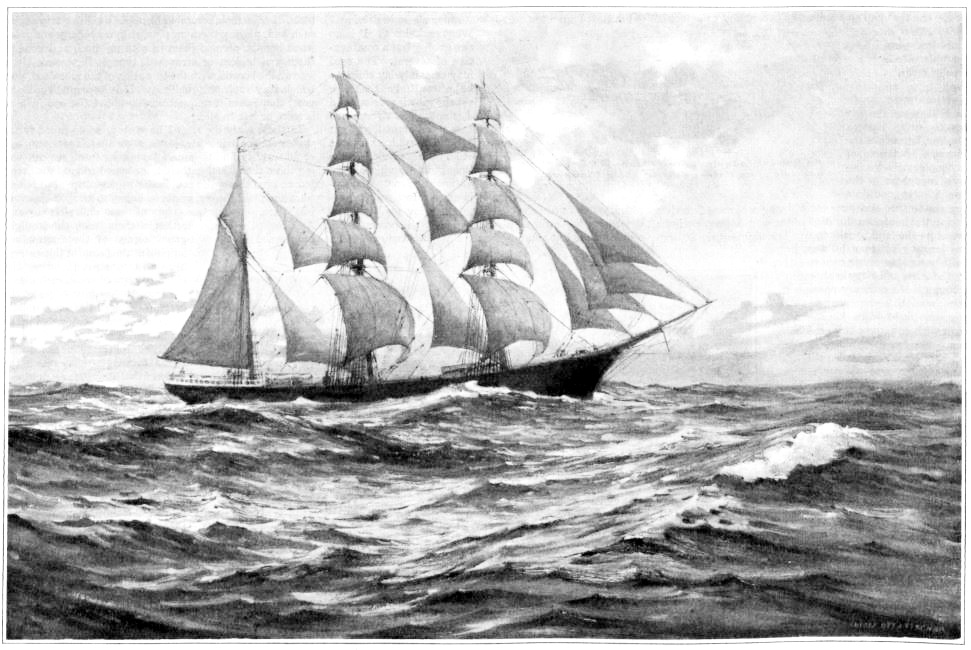

The captain was certainly driving that ship. Morning after morning the mate found him crowding on every thread she could bear. Day after day she went booming down the latitudes with a bone in her teeth and a white wake boiling astern. And day after day the small elderly mate, caught up into the accustomed routine of a ship, the orderly sequence of watches, the work of the day and the work of the night, found himself accustomed to the hidden things which worked in his mind, about the captain, who was strangely also his son.

He knew little more about him than he had learned at first. He had turned no more pages in what was practically a book closed and locked to him. The boy was there, intent on his work, vigilant, unsparing of himself, a capable master. His driving force might often seem like a force that was driven. His mouth never was allowed to slip into restlessness. What he thought — by the captain’s rail in the captain’s watches, shut in his own room nights, pacing the deck in some tranquil hour of loneliness before sundown, when the sea was roughened lightly by the good following winds — old Johnny could not guess.

But one thing the mate did know, and that was that in spite of himself he was growing proud of that boy. Day by day the warmth of that lifted in that empty place in him — lifted until the elderly man thought often he must be all lighted up with it like a church on fire. It caught him unexpectedly, in a long night watch or moving among the men or swapping yarns with the second mate. It crept over him suddenly like day out of the sea, and there he would be, in a breathless moment, blazing with pride.

He was proud of the ship, too, and the way the men were working, but he could talk about that pride. They were all proud of that ship, and they talked about it — the watch off duty forward, and the mates aft, having another cup of coffee after supper, with their elbows on the table and their eyes turning automatically now and then through the open skylight to the high piled sails, ruddy with the dregs of a great tropic sun. But the other pride was a secret thing, a thing he had all to himself, to hoard and hug to himself, rolled up in his bunk or walking silently by the helmsman, in the long nights or the blue, amazing afternoons.

Then the northeast trades, blowing fitfully over a sea smooth as bright hot pewter, failed. The ship rolled a little on the long polished swells, her yards creaking, her empty sails slatting. The sky was stainless; an infinity of blue burned a fierce white at the zenith, where the bare sun smoked. The ship’s rails were scorching to the hand. Her shadow lay short under her bows, blue fire, through which the dolphins arched their backs. Only smudges of light airs darkened idly the immense platter of the sea. The lowered careless voices of the crew at work in whatever shade they could find sounded loud in the dazzling stillness.

Young Captain Mat Brandon stood and clutched the poop railing with stiffened fingers. His forehead was ridged under his visor. The mate, with that quick old glance of his that always included the figure of the young captain in his observation of the ship, saw that the dark gray eyes glittered. From time to time he strode to the rail to see if in some vagrant air the ship had steerage way. But she lay heavily, with the swells hissing up and down her sides, as if she were anchored.

“The Old Man’s taking it hard,” the second mate muttered to the first, meeting him below the poop.

Old Johnny had no temptation to smile now at the humor in calling the captain that. He was used to it by now. He only frowned a little himself and changed the subject uneasily. He was uneasy, not so much at the hot calm itself — he’d lived through dozens — but at the mounting tension he felt in the boy. He could read every inflection of his, every muscle twitch, every suppressed, smoldering gesture. Annie had been like that. He had always been able to read the storm signs days before. Old Johnny would turn from his involuntary study of the young face with a half sigh. It wouldn’t do for him to be too much like his mother.

It was a long day before the captain would acknowledge that the wind had failed. He could not believe it — he would not at first. It was only a temporary lull. No wind could flat out so completely. The mate saw the growing bitterness in the boy, as if the weather were a personal injustice. Yet the steely hours wore on, burning and absorbed. The sun glared to westward slowly, with the round metal of the ship’s bells hurrying after. Behind the captain’s back, the man at the helm, one hand upon the unmoving wheel, whistled idly and long drawn out for the wind which did not come.

That night there was a moon — a great hot lopsided thing, slitting the hot black circle of the sea to lay its incandescence on the unwrinkling water and upon the ship. Her decks were bleached bone white with it, and the sails hung white and the shadow of the rigging lay across the decks, black barred like iron. The ship moved and dipped to the unseen milky swells alongside and all her sails slatted dismally. The watch off duty gathered on the fore hatch and men sang in a straggling chorus to the gasp of an accordion someone had brought on deck. The glaring white of the moon fell upon huddled naked shoulders and sprawling legs, and old Johnny could make out colors in the luminance, the dull blue of dungarees, the red of a mopping bandanna.

The captain’s boot heels sounded loud upon the planks. He stopped by the rail and spoke suddenly, gnawing his lip: “Damn that accordion! I always hate the things. I suppose that red-headed idiot’s playing it. That’s him yowling off key. I’d like to see his jaw knocked shut for once.”

“He’s a good hand enough,” old Johnny said mildly after a pause. It was the undertones of the boy’s voice he hated — too ragged, too much like Annie’s — not like the master of a ship.

“Of course you’d put in your oar for him,” young Mat said violently. “You and he are as thick as thieves. It’s the grinning way he acts I can’t stand. Smart Aleck. I’d like to smash that blasted accordion.”

“Got no call to interfere with a man off duty,” old Johnny insisted stoutly.

The captain said vehemently, “Aw, you’re an old — ” and stopped himself abruptly. “Listen!” he said. “Is that wind?”

There were no sounds except of the slack sails and the men’s voices forward. Around the horizon, below the blistering radiance of the moon, the stars burned steadily, like the lights of far-off ships. There was no wind. The captain ground his teeth on his burst of talk. The old mate kept silent. The captain resumed his dogged walk.

An hour or two later he stopped abruptly and said,” I shan’t go below much until the wind comes.”

He was on deck a long time. Old Johnny, coming up after the deep refreshment of his sleep, washed and sprightly, saw him having his morning coffee under the awning, his eyes reddened slightly with sleeplessness, his hair on end. The crew were cheerfully washing down the deck with a great splash and glitter of water from the brimming buckets. The redhead made some sort of joke behind his hand to the man next him and glanced aft at the captain, and the old mate hoped that Mat had not noticed it. The man was harmless enough and his joking was even valuable. Old Johnny had seen before this what heat and calm and inactivity could do to the raw nerves of men. He tried to keep them healthily busy.

He wished with all his heart he could do the same thing for the boy there, eating his heart out for wind for his first ship.

But all day there was no wind, and the next, and the next. Not a hatful, not a capful, not even a decent handful of air, to stir the heat which quivered up from the decks, where the glue between the planks melted and bubbled slowly. The men, stripped to their waists, went about their work with the sweat shining on their brown muscles, yawning in the widening or narrowing shadows of the sails. On the unstirring plate of the sea the shadows of the topmasts, like blades of a sundial, lengthened and wheeled and shortened under the sun.

The maddening futility of the dead calm was drawing the crew into silent and uncertain tempers, as old Johnny had known would happen. Tension seemed to spread to them from the gaunt young figure of the captain, his somber face drawn and blackened by the breathless sun. He would stare with blistered eyes at the blazing surface of the ocean, standing by the rail so long and so rigidly that the crew glanced up at him more often than ever, and whispered among themselves. Sometimes he paced doggedly, sometimes he dashed below for a mouthful of water or a bite of food taken hastily, glancing up through the skylight to see if the wind had come in his absence from the deck.

Among the crew bad feeling bred, and endless small explosions of wrath. Old Johnny played endless games of double solitaire with the second in the breathless nights, feeling the heat as nothing beside the mounting tension on the ship. His bright observant eye saw everything. In a low voice, so that it would not annoy the captain, he spun long picturesque yarns that kept the second mate’s blue eye bulging and drew the cook and the steward to the pantry threshold, with their eyes eager and their mouths grinning. He loved to hold them like that by the color and cunning of his words. It kept them good-natured — and him too.

But he could do nothing for the captain. That was about what it meant to be captain of a ship. Nobody could do anything for you. It was all on your shoulders. The fact of that was an isolation. That was why old John had never had any hankering after a command. He liked to be closer to people than that. But now, without any interest or desire on his part, it was almost as if he shared the feelings of command through the nerves and body of his son. It was a curious feeling of double existence, and it made it worse that he could not substitute for the younger tension his own older stability and understanding. He grinned often at the irony of it. But there it was, and it got worse.

The captain was taking his balked will out on the crew in irritating and — or so it seemed to the mate — unreasonable orders. He lashed at them unexpectedly for almost invisible faults. And the small red-headed man was his particular victim. He kept him down painting the sail locker by the light of a lantern all one stifling day, from which the mate later had to haul the man, nearly all in, on a pretext. The uncertain tempers of the crew flamed at what they considered persecution, and furious looks and mutterings were turned aft toward the figure of the captain. The mate walked steadily among the men at work, with his voice steady and his eye cool, and that night at supper took without a word a burst of anger from the captain. He did not mind the anger. He was only deeply worried that the boy should have himself so little in hand.

Three days more — four days, and no wind but a light current of air which carried them southward for an hour and dropped them in the same center of the same brazen, unchanging circle, that went white with sun or purple black with the sun’s passing, like a slow shutter turned on and off. Tension ran like a red-hot wire through the men cooped forward between the blistering bulwarks. One corner of the captain’s mouth slipped from its tightness and he gnawed it endlessly.

That night, in the middle of his own watch, when the captain had been below for an hour trying to get some sleep, old Johnny had a sudden impulse to go below also. Or perhaps he only wanted to reassure himself that the captain was asleep. The second mate’s snores were vibrant from his own room. But in the dim stifling light of the cabin, with the lowered lantern and the starlight streaming in, the old mate stopped abruptly and felt his knees tremble.

The door of the captain’s room was open. There was a dim light in there also. The captain was standing with his back to the doorway and he was pouring something out of a long bottle into a glass.

Right then old Johnny knew how badly the boy wanted that drink, because he wanted one himself with every fiber of his old body. He had never needed a drink so badly in his life. He could have snatched the bottle from the hand and drunk from it with the sudden hot force of the desire that burned him. Yet that familiar pose, the tiny sound of liquid pouring, was like acid eating into him — because it might be that in this the boy was like him. If he were like him, old Johnny knew, and clenched his hand on the table edge to realize, that one drink was not going to be enough. The warm relaxing that would work along the fingers, the blurring of the painful edges of reality, the delicious approach of oblivion along jangling nerves — old Johnny knew all that. He ached for it at that moment. But it meant drunkenness. His old fist slammed on the table. Not drunkenness for the captain of a ship!

The sound startled the tall young figure. He turned around, the bottle in one hand, the brimming glass in the other. In the half-light, his eyes met the fixed gaze of the old man with a desperate glassiness.

The older man said slowly, “I wouldn’t, sir, if I were you. It’s tough on you. I can see that. And a drink would go good. I’ll say that myself. But I wouldn’t if I were you.”

The glassy eyes held his as he spoke with nothing in his face or voice but quietness — no tension, no accusation. He thought for a moment the boy would raise the glass to his lips and drink anyway, from the spasm that contracted the face suddenly.

But presently he dropped his eyes to the glass as if he had not seen it before and said huskily, “What’ll I — do with it, then?”

“Throw it out the porthole,” old Johnny said evenly. “And the bottle with it. There’ll be better bottles in Rio, when we’re off the ship.”

They listened to the small splashes in the dark sea outside there and the old man ached a little at the face young Mat turned to him. There were deep lines of sleeplessness in it, but the eyes were not the hot ones of a thwarted drunkard so much as the bewildered ones of a little boy.

“Come up on deck, sir,” old Johnny said, and if his voice was tender he couldn’t help it. “It’s stifling down here. I’ll have your canvas chair brought up. You’ve got to let yourself go a little, you know. This calm won’t last forever.”

The night was at least quiet, up there — so quiet it seemed they could hear the dew dripping from the sails. The air was lukewarm, like half-cooled tea, but at least it could be breathed. Men forward, sleeping half naked on the fore hatch, moved arms or legs uneasily and the watch about the deck were listless drooping shadows.

Old Johnny had the captain’s canvas chair set in the deep shadow of the rail. But for a while the boy stood with his elbows on the broad rail, and old Johnny put his elbows on it and leaned beside him. Down in the milky gray of the sea alongside phosphorus stirred with little stirrings of the surface, soft brightness licking along the still timbers. Old Johnny wrenched his mind hastily from his thought that that rum bottle might be floating down there, bobbing about, where it could be picked up with a bucket on a line. The boy’s shoulders were beside his.

Old Johnny found himself fumbling in his mind for the most gorgeous, the longest-winded yarn he knew, and slowly found it, glittering, in the depths of his memory. He began to pay it out gently, every word in its right place, the suspense built up with little pauses. Under the stir of its events laughter ran like a healing flame. It was the best tale he knew, and he told it of himself and Bill Broadhead — a tale of a ship derelict and haunted in tropic seas, an old stocking full of pearls, an island of hidden temples and birds like blazing emeralds, and Bill Broadhead fighting with a cutlass up ruined stairs in moonlight, that led to women’s laughter and a huge escape. He knew, as the young head beside his was held rigid in the glamour he cast cunningly, like a net, that he had never told the tale better in all his life. He knew he had never told it with so serious an intent.

When it was over and the hour was gone he stayed silent until the boy beside him moved with a half sigh, moved and stretched and grinned.

“That was one swell yarn,” he said lightly, and his face was easy in the glow of the starboard lantern — “one swell yarn. A stockingful of pearls, eh? I bet that feels nice in the hand. Wow! I guess I must be sleepy.” The canvas chair creaked a little under his weight. Old Johnny did not move from the rail. The idle sails slatted a little with the movement of the ship. Presently he turned around and looked over at the long figure in the chair. It was still, and a hand was heavy on the deck. The captain was asleep. Old Johnny stood there, not moving a finger, staring down. Deeper than the awakened desire for drink an ache moved in him. There was something about those young bony knees that broke his heart. It was as physical as that, as if something clutched and tore his heart wide open. The worst of it was, he could do nothing to help him — not one thing.

The actual pain of that astonished him. He would not have believed he could feel like that about anyone. It drove him back to his need for a drink. He felt as he had used to, coming off a long dry voyage, burning up with thirst. Well, he’d just have to go thirsty, that was all. He’d thrown away his chance, he told himself with grim humor, and it wouldn’t do for the mate to be seen fishing off the poop with a bucket. He’d have to drink water, and like it, and pray for wind. He did, at that.

The next night there was a fight forward, sudden as the breaking of a stretched wire. Old Johnny had been expecting it. The men came tumbling from the forecastle to form a muttering rampart about the locked dark figures swaying and grunting and grappling in the shadow. The captain watched with a furious face, but old Johnny strolled forward. The men were not too intent to make way for him, and he stood there watchful and alert.

They were not fighting with knives, he was glad to see. There was the thud of bare feet on the deck and the smack of honest blows on bare flesh. The circle of the men shifted with the shifting of the fighters. And in a gasping bit of silence, when the slippery bodies clinched and fumbled, old Johnny raised a remark or two, the heavy broad wit men liked, and listened appraisingly to their sudden roar of laughter. Presently, in another pause, amid more laughter, the men were separated and helped off to wash. Old Johnny strolled aft again, with the relaxed voices of the crew behind him, drowsy as bees after a swarm.

The captain’s eye was a dark coal as he went up the ladder. “I won’t have fighting aboard my ship,” he snapped. “Another time you can have them clapped in irons. I won’t have it, I tell you!”

“Just a scuffle,” the old man said easily. “Ought to have boxing gloves aboard — take the edge off them.”

“I begin to think you’ve a poor idea of discipline, Mr. Mate,” the captain said furiously. “How’d you expect me to run this ship with a soft crew that isn’t taught a proper respect for their officers?”

The old man looked him mildly in the eye. “They’ll work all right,” he said. The captain snorted and walked away. Old Johnny looked after him reflectively. Now the boy’s mother, after that, wouldn’t have spoken to him for three days.

But he had not to wait that long. For that afternoon the sea darkened fitfully in long widening fans, and wind moved, ruffling and undependable, about the ship. The sails filled slowly to a fresher breeze that presently blew west by south, blowing away the stifling exhalation that hung about her. The ship answered the helm. The watch sprang smartly to trim the yards, and the captain, hearing the shouts of the mate, the thud of feet and the creaking of tackle, let all the tension slip from his face in one long grin. But no sooner was the ship an hour or two upon her course than the wind drooped and died, and the ship lay again becalmed. In another hour a breeze sprang from a totally different quarter, so swiftly that the ship was almost taken aback. The yards were squared. The ship heeled slightly on another course. And in four hours more, in a glassy moment of twilight, the breeze left them altogether.

So it went for five days of variable, inconstant, heartbreaking airs. The captain chewed his lips over his charts and at his sights, and his face was drawn and dark. The men dropped into their bunks after duty, worn out mentally as well as physically by the constant fret of labor that did no good. And the old mate began to know that he was old. There were twinges in his back after a long watch, such as he had never felt in his life before, and when he went below to his bunk his legs felt a thousand years in them. His vigilance, his spring, was outwardly as good as the younger man’s. But inside him it was as if a bell had been struck. Yet with all the force of his inherent pride he fought all that off, aches and slowing up and sleeplessness and an unresting, burning desire for a drink. His jaw was tight and his eye was keen. The captain did not call him easy now.

At last, after a night of dead calm, the ship began to move steadily forward. The light was pearly, the greenish waves edged with slate. As the day gathered under slow gold swords striking upward behind low clouds and across a long sea, the breeze freshened and the foresail filled. The captain and both mates stood on deck to watch the ship go forward in the new clean light and it was as if a tight band had snapped from about their chests. They were out of the doldrums at last.

“It will hold,” the captain said, with sleeplessness bleary on his eyelids. “Call me if it doesn’t.” And he went below.

After four hours the captain came on deck again. The wind was fresh and strong. The cordage hummed. On the yards the great spread of canvas held stiff overseas foaming in sapphire, touched with frothing vivacious lines of white. The captain’s face was scrubbed and jubilant, but the driving force, new-lighted, blazed in his eyes.

Now the Mary Parsons moved steady as a steamer under the roaring glorious south trades, and old Johnny gloried to see her go, never once relaxing that cautious grip he had upon himself. It would not be two weeks to Rio in this wind.

There was a week left — five days — four days. The crew were tidying up the ship for port, scraping teak, polishing brass, painting interminably. A pleasant sense of journey’s end ran about them. Only the captain did not relax in it. He was still feverish to make time, to get the voyage done.

What happened thereafter happened like a clap of thunder on a clear day. There were only three days left before making port and already the wind was shifting a little, tainted with the land. To westward a sullen bank of mist lay low like dirt-colored mountains.

Old Johnny came on deck in the middle of his watch below the next morning, drawn by the changed color of the light and the abrupt motions of the ship. It was racing and bucking against a sea of fretted heaving milk under the damp blast of a sullen southwest wind. The helmsman stood stiffly, his anxious eyes on the sails, fighting the jerked rudder. But the captain had not shortened sail. The watch forward were gazing at the sea and at the sails, and then aft, as if awaiting an order. The captain stood like an iron post by the rail and his face was iron.

Old Johnny hurried up with the wind in his blinking eyes. “What about shortening sail?” he shouted. “I don’t like the look of that. It feels like a pampero.”

“Pampero your eye!” the captain snapped. “You’re getting old, Mathew. You’re losing your grip. Want me to run before every little squall, do you?”

“But look!” The mate clutched the younger arm.

The bank of dirt-colored cloud was climbing the sky fiercely. Through it lightning spread in seams and below it the sea went the color of dirt. The ship plunged and pitched in the damp uncertain air that pushed the men in the face. The captain tightened his jaw and shook off the hand impatiently, turning his back to the wind.

Then — pandemonium. Old Johnny was aware of a vast force which fell like a stone upon him and upon the ship — a force demoniac and shrieking before which the ship reeled violently. Above in the screaming murk a sail blew out like a shot from a cannon. In the constant ghastly flicker of lightning he saw it flash whitely once down the wind. He was struggling to turn his body about and open his eyes and shout an order. But his voice was crammed back into his lungs. The slant of the deck before him was a high hill, racing with stinging rain.

The ship righted herself with a long shudder and the wind caught her, and forward there were crashings and poundings and a boil of sea over the weather rail. As he stared wildly through half-opened eyes he saw the fore-top gallant sheet give way. The gallant sail straightened out like a plank, straining the mast until it quivered and bent. In the instant the fore-royal and gallant yards broke off with a shrieked crashing, toppling down on the streaming deck among the hissing flight and tangle of ropes. One man was knocked down like a belaying pin and rolled into the lee scuppers. The others scattered where they could. The debris hung half over the lee rail, bumping dangerously, and the ship listed to it under the ghastly foam pouring over the lee rail.

The captain’s voice, that strained the blood vessels on his forehead, lifted faintly across the wind. “All hands! Leggo main royal and gallant halyards! Lively! Another blow — ”

The men swarmed to the order, slipping and struggling and catching at the fife rail as the ship reeled, shuddering, and the roused sea struck viciously.

“Axes!” the captain bellowed through cupped hands. “Axes — wreckage — adrift!” And with the old mate at his heels he raced down the ladder.

They were immediately above their knees in the sea that shipped regularly over both rails. Old Johnny gasped with the cold of it and the wrenching blows of it on his body. The murky light was lifting and now it seemed that the wind struck with less force, but it was a back-breaking job to swing axes and keep footing. Old Johnny heaved his with the packed force of every muscle and his son’s heaving shoulders were beside him, in the tail of his eye.

The wind screamed suddenly and behind the captain’s head a huge sea lifted a dirty edge over the rail. It crashed inboard, shaking the ship. Old Johnny had dropped his ax and clutched the rail, but almost as it toppled he looked for his son, letting go his clutch to leap toward him, yelling, “Mat, look out!”

He felt a terrible wrenching heave and under the ton of cold water that fell on him something that might have been a rope caught him about the knees. The world heaved violently, whirling, and became a seething drop into darker water, bottomless. He gulped wet bitter salt, whirling and staring into boiling dark depths. Something crashed into his ribs and the pain sent him dizzy, even as he had a flashed glimpse of the ship to windward, and a gulp of air. He clawed the air with a dripping hand and shouted. “Mat — Mat!” he yelled, and yelled again, before he was knocked into blackness and oblivion.

When he came back into the world, it was slowly, among mists of weakness that were curiously delicious. His body was a vagueness in which he floated and in his fogged glance grew slowly the familiar white-painted planks with bolts in them above his head. He recognized that the ship was moving easily, even as he knew the handles of the chest of drawers built across the wall at his feet. Oblivion caught at him from time to time, and he sank back into it gratefully, among thronging hints of dream. But clearer and more persistent than those were the drawer handles and the white-painted bolts and something round and whitish that slowly became the steward’s face, before it changed to the face of his son, the captain of the ship.

He was broad awake then and his body was a battered thing between immovable tightness, but he could look about him with clear eyes and a clear head and see his own gnarled old hands on the blanket and the buttons on his son’s coat. He grinned slowly.

“It feels as if I got run through a meat grinder,” he said. “How’s the ship?”

“Booming along in,” Mat Brandon said cheerfully.

The old man took a long slow look into the boy’s face. There was an untidy bristle of beard on it, and it was white and lined deeply with fatigue. But the locked look was gone from the mouth and there was no fever in the gray eyes that met his calmly. New warmth ran through old Johnny as staunch as his own heart’s beats. He liked the released look on that face — by ginger, he liked it!

“You’ve got a couple of busted ribs on you,” the captain of the ship was saying. “The steward and I fixed them up as well as we could according to the book, but I’ll be glad to get you ashore to a doctor. We’ll be in tomorrow sometime. How do you feel?”

“Comfortable, ’s a matter of fact,” old Johnny said. He was discovering that he must not breathe too deeply. An arrow of pain lay there, as if in waiting. And he was growing aware of many aches. “How’d I get aboard?”

“That red-headed feller,” Mat said. “He jumped after you like chain lightning and we slung him a rope. His collar bone’s broken. You know I — it’s funny, but I’ve been wishing right along, since then, that I had gone over for you myself.”

“Crazy,” old Johnny said slowly, trying to stiffen his lips against a grin. He was watching the boy’s unconscious face through half-shut eyes. “That’d been a fine thing to do, and you the master of a ship!”

“Yeah,” the boy said slowly. His elbows were on his knees and his eyes were on his loosely clasped fists. “Of course I knew that. But you know I’ve been thinking — it was my fault we got overtaken that way. I was wild not to lose any more time.”

“Aw, those pamperos — you can’t ever tell about them. You’ll have to remember you got to keep your eye peeled along this coast. And you’re right about being wild. You’ve been kinda too strung up tight all this trip. You better not be like that another time.”

“I know,” Mat said shamefacedly. “I don’t know what got into me. But I guess I got to worrying about that mate. I’d sort of like to tell you about the mate.”

“No need to if you don’t want to,” old Johnny said briefly, with his eyes screwed tight and his heart thumping.

“I been wanting to all along. It kinda got into my head that you thought I murdered him — or something. And then I got to worrying about what the owners would do if they heard about it. That’s why I was so wild when the wind failed, and afterward, when there was a chance to make up the time. You see — the mate got himself drunk. You remember. You were there. But then I got him drunker than that and I had him hidden. That Yellow Charlie had him taken to a shack out in the jungle somewhere. I paid him. He wasn’t hurt any. You see, I wanted the ship more than he ever did. It was a rotten trick, of course. But I’m not sorry.”

“What you going to do about it?” old Johnny said suddenly, opening his eyes.

“Nothing yet,” he said, meeting the old man’s eye firmly. “There’s nothing sensible yet to be done about it, except going up and telling the owners just how it was when I get the ship back to New York. Maybe the mate’s made a howl by this time. I don’t care. I’m going to prove to them I can handle the ship for them better than he could. And I want to say — I’ve got a lot to thank you for. You’ve taught me an awful lot.”

“Aw, shucks!” old Johnny said weakly, shuffling his hands on the blanket. “You were only a stiff kid. Man’s got to grow some to be a captain. I followed the water and learned the different ways of captains before you were born. And you’ve grown. I can see that. You’ll be a good one. It’s like you had good seagoing blood in you and a will to do things well and smartly. Only you don’t need to take things so high-strung.”

“I’ll tell the world you get steadied,” Mat said absently. “I feel years older. I wish you were going to be along on the voyage back.”

The old man looked steadily at a bolt over his head. That’s right. He’d be in hospital again. And after that — The slow pain dug into him at his deeper breath. Oh, well, why worry?

“Maybe you’ll drop me a card from New York,” he said. “I’ll be curious about — the ship.”

“I’m going to do that,” Mat said slowly. “I’m sure going to do that. And you’ll write me when you get well, whether you get another berth or not. It might be — we might ship together sometime again.”

“I won’t be holding many more mate’s jobs,” old Johnny said calmly. “I’m pleased to know you’d like to, though.”

“Well, you’ll let me know,” Mat said, getting up. “I’d kind of like to know. I’ll tell the steward to bring you some soup.” In the door, he stood a moment and turned back. “You’ve never said” — he spoke slowly — “whether you’ve got any folks or not that you could go to. I’ve wondered. Haven’t you got somebody — a son — somewhere?”

The grin that spread over old Johnny’s face at that could not by any force of his be repressed. His eyes leered a little in sheer delight at the joke of it as he looked up into the other’s concerned face. Poor Annie, how she’d hate it if she knew how her son stood there, looking down at him with anxiety and — yes, there was no doubt of it — with affection. How she’d hate to know that her worthless husband was actually being cared for by her son. Well, he’d keep his promise to her.

“No,” he lied cheerfully, “I haven’t got any son.”

After Mat had gone out he lay there, wrapped in comfort, his mouth still twitching at the thought of it with something very like a giggle. Deep down in the place where his pride lived, that would not let him explain or regret or ask quarter from his world, the increased flame of it lifted in a great warming glow.

He’d been weak and mistaken and foolish in his time. He’d been proud, without having much of anything to be proud of. But now, he thought, a king couldn’t be any prouder than he was or had the right to be. Now, by Jupiter, he was the father of a man!

Featured image: Illustrated by Anton Otto Fischer.

“One of Us Must Die” by Edmund Gilligan

Edmund Gilligan wrote for the The American Magazine, Cosmopolitan, Argosy, and the Post between 1956-1962. His short story “One of Us Must Die” covers the enthralling tale of a crew battling the sleet-chilled Atlantic waters while at sea.

Published on September 8, 1962

By lamp-lighting time alongshore, the Medea of Gloucester lay sound asleep at the herring wharf in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, where the Roseway River empties into the Atlantic. The schooner had hurried across the Bay of Fundy under a whole mainsail because she had never gone fishing so late in the year, and her people wished to find shelter to size things up. There had been signs of bad weather far behind her. Off Cape Sable, her landfall, she had found more reasons to hurry. The westerly wind had become curiously dry, and the barometer had risen. Later she had sighted hurricane rollers rising out of a very long swell. When she swept along the western edge of Roseway Bank, the squally halo around the first quarter moon had vanished, and the barometer had fallen to “Fair.” So she slept in peace, the uneasy peace of November.

Huddled under the eaves of the icehouse, three dark-clad men gazed at the Medea as she lightly rose and fell to bow line and stern line, her iron gear atinkling. By moonlight and starlight the Medea displayed her old-time beauties: bottle green hull, cherry-stained bulwarks, white crosstrees and her name in gold, mildly gleaming under skeins of frost. Those men knew the Medea well enough, and they knew why she lay there: to buy their herring in the morning to make bait for the halibut on far Banquereau, which was her workshop. Herring they had in plenty on ice, and the sale meant much to them, coming so late in the season. They would have a little more Christmas money. They understood that the Medea had dared to make a November voyage for the same purpose. There had not been much money earned that fall on the Grand Banks; the price of halibut had been too low at Boston. Now it had risen.

Talking of these matters, they crossed the wharf, took a kindly look at her mooring lines and walked up the lane, praising the fatness of their herring and declaring the Medea’s skipper surely would be pleased when he ran his testing thumb down the herring bellies and found them fresh.

In the galley of the Medea, aft of her forecastle where eighteen of her dorymen slept in their tiered bunks, one man stayed merrily awake. He was her cook, known to the Grand Bankers as “Long Tom” because his handsome head, well silvered now, lay so far from his feet. The dorymen asserted that in any kind of fog he couldn’t see his boots. He answered that his boots weren’t worth such a difficult glance anyway.

Tom had finished his ordinary chores. Mugs and dishes were washed and put away, his pans scoured. He had just taken twenty loaves of bread out of his great oven. In there now his apple pies were already adding a cinnamon bouquet to the other delicious fragrances. He had yet to brush the top crusts with a gull’s feather dipped in butter. The feather and butter were at hand.

At the moment, Long Tom was resisting temptation of the worst kind — one offered by himself. He was a cook who enjoyed his own cooking. In fifty years of labor in that one galley he had never tasted a dish which he could not praise. And he tasted all that he made. Even when he hard-boiled fifty eggs for the shack locker, where dorymen coming off watch could “mug up” on tea and cookies, he always ate one or two to make sure. His chocolate cake had made the Medea the envy of the Gloucester fleet. Such cakes bore fudge icing, and Long Tom couldn’t tolerate an icing less than half an inch thick.

His present temptation had a chocolate nature too: precisely, a yard-square tray of fudge cooling on a shelf under the half-open port. He had used the last of his Jersey cream for it, and he had put into it an array of excellent English walnuts. He had a benevolent purpose in mind, and he intended to carry it out when the fudge had hardened enough to be cut. He had to combat his desire to taste. To that resistance he carried all the force of his plumpness and of his agile mind.

At such a crisis Long Tom took refuge in the Bible, not exactly for instruction but chiefly to employ his mind. The Book of Job had served him well a thousand times. Long Tom had never quite settled the question of Job. “Patience of Job, do I hear you say? Why, he don’t strike me as being a model of patience. What answer did he make to his chum? ‘Wherefore do the wicked live, become old, yea, are mighty in power?’ And didn’t he come out all right in the end? Aye, there’s something of a sea lawyer about that man. Shouldn’t be surprised if he’d once been before the mast — and a poor cook in the galley.”

When he had beguiled his heart by thoughts of Job and Satan, he turned in a soberer mood to The New Testament, in which he always read much during the Christmas season. “Matthew, Mark, Luke or John?” He chose John, and for a time he sat enthralled, because these were saints whose hearts spoke well to his. He placed the Bible in its tin box and turned to the cutting of the fudge. He had all but finished when Satan whispered, “My dear Job — I mean, of course, my dear Tom — isn’t that a rather odd-looking piece over there south by east, a little east? I mean that one with a whole kernel in it.”

After he had eaten it and savored each crumb to the last, Tom looked behind him quickly and seemed surprised. “Well, now, I really didn’t have to do that. I knew it was good, very good.”

He filled three plates with fudge and climbed the companionway step by step, carefully. On the way aft he paused in the lee of the starboard nest of dories and measured the starry night. The Pole Star burned fierce as a bonfire, and he could make out even the faint stars of the Little Bear, so clearly they shone in the winter hovering aloft. He passed to the cabin and went below into its dusk. He put the plates down and rapped his knuckles against the great lamp, burning low in its gimbals. It was his duty to keep lamps trimmed and full.

In the starboard bunk Captain Matthew Duane lay asleep, his boots near at hand, ready, even in harbor, to be jumped into. Under the black curve of his moustache his lips shaped a stern word. He frowned and gently struck his mouth, just as if it had spoken of its own accord and had vexed him mightily in his dreams. “I’d give a lot to know what he said,” whispered Tom. He gave a plate of fudge. The skipper whispered again and began to turn over, his secret kept.

Long Tom stepped lightly to the port bunks. In the lower one lay Dick Rodney, the oldest hand in the Medea and the best sailing master ever she had. She liked him, that vessel did, and willingly performed things for him that she would not for others, especially when close-hauled and beating to windward to hit the lively Wednesday market at Boston. Neither chick nor child did that man have, as they used to say of bachelors in the bygone days. On the Medea’s tenth birthday he had come aboard, a greenhorn, and he had never left her even to lay off one trip. The sea and the oars and the hauling of halibut had shaped him into the Atlantic style: heavy-shouldered, lithe in the long legs and able, very able, in the many uses of the great frost-scarred hands calmly folded together in the grace of dreamless sleep. Dark hands they were, half again as large as the cook’s, and his were not a boy’s hands by any means.

“Happy birthday, Dick,” whispered Long Tom, although it wasn’t anybody’s birthday and he was just trying to entertain himself. “Happy birthday — and may you have another one very, very soon.” He placed Dick’s portion at the foot of his bunk, where his pipes lay in a rack of white porcelain, an ancient thing with odd English words on it that had been fished up one day on Sable Island Bank.

In the upper bunk a man lay awake. Long Tom had no difficulty in standing face-to-face with him; he was tall enough for that. Such wakefulness surprised Tom not at all. He had expected it; in fact, this doryman — greenhorn, rather — was the reason for his night visit. He knew well enough what must be the thoughts of a youngster on his first trip to stormy Banquereau — and in November. He had known the lad’s father, Dennis Nolan, a good man in a vessel and, in a dory, the best of dorymates. Now he saw in the gazing eyes and the thick wheaten-colored shock of hair the father’s eyes and the father’s head. The young man’s forehead shone white in the dim lamplight because he had been living ashore. On the voyage across Fundy, Long Tom had watched the new hand with affectionate care and had helped Dick Rodney in the schooling of him, for Dick took charge of the greenhorns one by one through the Grand Banks seasons. This one now required something more than lessons in seamanship.

“You don’t sleep, young man?”

“No, sir, I don’t. I’ve been thinking — and it keeps me awake.”

“You’ve Dick Rodney for a dorymate, and he’s taught you well coming over, so you’ve no cause for worry, David.”

“You both been good to me, cook.”

“And I brought something for you right now.” He held out the plate. “Just you take some of this, David, for I know you’ve a sweet tooth, and a sweet tooth satisfied — ah! that puts a man asleep. So I guess you’ll be all right, young man, if now you take another piece and fall asleep and sort of work up an appetite for breakfast by the right kind of dreaming. Aye, the young need sleep. And so good night.”

In the afternoon, after her bait had been stowed in ice, the Medea took the tide that served her. Under headsails only, she passed through the harbor entrance and, once outside, laid on all her muslin and was soon running free to the chosen fishing grounds.

Now, standing among the other dorymen on her streaming deck, young Nolan learned to cut bait in the larger chunks required when a vessel is rigged for halibut. Dick Rodney stood by him and showed him how to thrust the chunks onto the big Norway hooks, hanging a fathom apart on shorter lines tied to the main line of the trawl. He taught him the skill of coiling the baited hooks on squares of canvas to be lashed into bundles called “skates.”

“And once a halibut has taken hold,” said Dick, “he ain’t hard to haul — not in winter, I mean — because we’ll be fishing in eighty fathoms maybe, and he’s dead beat by the time he tugs all that way. Now in summer, when you take fish in forty fathoms, they have a short fight coming up and come to the gaff strong and frolicsome. You understand me, my boy?”

“Yes, Mr. Rodney.”

“Ah, you must drop the ‘Mister’ now, David, though it’s real respectful like of you and all right in the beginning and shows your good breeding, but now you must learn to call me ‘Dick’ because we’re dorymates now and forever friends, the best of friends, depending entirely one upon the other in the dory. Besides, you may be calling out a warning sudden like, and ‘Dick’ is the quick word.”

“I’ll do so, Dick.”

Before sunset the westerly wind became very cold and a fine rain fell, almost a mist. Everything cleared up for a time, and the sunset took on a violet coloring. Before the sun really got down, a cloud bank under it changed to a purple hue. Squalls burst out of that bank and ripped along the horizon, making quite a rumpus over the tide rips. Despite the unsteady nature of the weather, the Medea plunged into the dark night and, without taking a reef or changing course, crossed the Sambro Banks and swung away until she changed course to go along the southern edge of Sable Island Bank.

During this sailing toward the Gully of Banquereau, where the gear must be put to work, Dick drilled his greenhorn hard until he knew the use and place for each tool of their trade: bailer and water jar, bucket and food tin, the gaff to hook fish and the gobstick to club big ones. He showed him the bottom plug of their dory, which is knocked out when the dory is hoisted aboard. “In this way, lad,” he said, holding up the plug in his right hand, “brine and blood can be hosed out through the plughole and — watch now! — in this way the plug is jammed into place before we lower again.”

“Dory away!”

Obedient to this order shouted by Captain Duane near the helm, Dick Rodney’s dory, No. I of the starboard nest, came swinging out, and the dorymates went down in it for the opening of a brisk campaign.

Young Nolan sat to the oars and took the direction of the set from the captain’s extended arm: southward. Dick sent down the first anchor to hold the trawl, and after it he flung the buoy carrying the dory’s flag. He took up his heaving stick, a willow wand cut in the marshes of home, and began the deft lifting and tossing of the baited hooks, coil after coil. The baits sank, score by score, down to the halibut roving along the hills and valleys of the ocean floor. With the first skate down, Dick tied on another string, and young Nolan rowed on, eagerly watching the clever hands, the great arms and shoulders bending, swaying at their tasks.

Meanwhile, the Medea, under jib and jumbo, glided northward, dropping the other dories. She came jogging back again, and at eight o’clock, when the sun was well up, she gave the fishing signal : two whirls of her horn crank.

“And now I’ll haul, lad.”

Wearing the white cotton gloves of his trade, Dick laid the trawl line over the wheel of a gurdy set near the bow, and he bent down to haul. The first few hooks came up untouched; the next one brought from him a cry of dismay.

“Dogfish! Drat ‘em!” He slatted the twisting fish against the gunwale and knocked it off. Over the quiet sea came the same slatting noise repeated in other dories, a dismal sound for all hands because it showed that the useless dogfish were swarming below. The shouts of anger soon ceased. The dogfish had fled before the voracious halibut.

“Greenhorn luck, lad! Here he comes!” Its eyeless side uppermost, a halibut five feet long slanted violently to the surface, its snout tugging hard against Dick’s strength. It thrashed in such force that a torrent of foam quite concealed its mottled, rust-hued length. For an instant it floated in an idling way and then turned over ponderously until the two eyes on its right side stared upward dully. Driven by a quick frenzy, it tried to dive. The tight line checked the halibut’s thrust, and at that moment Dick swung the gaff down into the space between the eyes. He hauled on the gaff with both hands until the fish came over the gunwale. Dick struck three times with his gobstick before the fish ceased to struggle.

For the next three days Dick and young Nolan labored from daybreak until moonrise over their trawls, and often they pitchforked their fish aboard the Medea by the light of oil torches on her deck. On the fourth day Dick let his dorymate make his first haul, and up the fish came, hook after hook. Each conquest excited young Nolan until he laughed aloud and struck the gaff so fiercely that Dick had to caution him to take it easy because the dory had almost a full load.

“Hey!” Young Nolan shouted in amazement at the repeated surge far below of a fish that drew the gunwale down. An immense halibut had taken the last bait, and the gashing steel drove it rampaging down and away, back and forth. “Ah, Dick, he’s thundering big!”

Foot by foot, fathom by fathom, the fish yielded to the unfaltering strain on the line. Despite the freezing wind, and the sleet-chilled water, young Nolan sweated over the gurdy. His breath blew vapor out and he gasped harshly. He bent far down to renew his hold on the line and heaved so strongly that the fish came swerving to the foam. Maddened by the hook, it flung its bulk grandly against the dory. In falling, the halibut struck a blow with its tail that actually drove the dory off in a sideways glide.

“Now then, David!”

At Dick’s signal young Nolan swung the gaff high and swung it down and into the massive head. This first blow stunned the fish. It lay sluggish, and thus young Nolan got his chance to club it three times with the gobstick. The fish shuddered its fathom length. Its tail sagged and its gills spurted water with an odd choking sound. The fish rolled on the surface, and they saw that it was by far the greatest yet taken by the Medea. No one man could haul such a fish over the gunwale. Dick lifted his own gaff, drove its blade into the thickest part of the tail, and hauled.

At that very instant, from far off, where the Medea sailed among the other dories, there came the wail of her horn, three times howling the danger signal: Cut! Cut all gear!

One upward glance revealed to Dick the onrush of a squall in which streams of sleet glittered. A November northwester had caught up with them at last. Out of blue water there had risen a black, whitecapped sea. A second comber bulged in its wide path. Both seas joined and doubled in a wave that exploded against the dory. Even such an assault could not overwhelm a Gloucester dory. Its high sides and solid gunwales had been designed, through the Grand Banks centuries, to withstand such shocks and to yield sturdily before them. So their dory slid off smoothly. Half-hidden in the welter of that sea, Dick shouted the Medea’s signal: “Cut! In the name of God! Cut your gear, David!”

Young Nolan had already obeyed the Medea. In a sweep of his bait knife he sliced the line that held the halibut. At this sudden end to the strain, the halibut’s head sank down with such force that the gaff sprang free and rose in David’s hand lightly into the darkening air. Carried high above the gunwale by the sea, the halibut strove hard for a diving thrust of its tail. This furious action had the effect of raising its head once more. In this position it thrashed its tail and head in a vaulting action out of the water and into the air. It fell, and its great mass struck full along the gunwale. The dory turned over.