Everything We Thought We Knew About Salt and Health Was Right

Unlike sugar and trans fats, we might accept salt in our food as a human necessity, an ancient mineral that conveniently boosts flavors in bland fare.

But we’ve been fed a line about sodium chloride. That’s what Dr. Michael F. Jacobson claims in his new book Salt Wars: The Battle Over the Biggest Killer in the American Diet.

For decades, Jacobson has worked with the Center for Science in the Public Interest — a group he helped found — to advocate for tighter health regulations on American food, writing a heap of books along the way advising on the science behind nutrition.

It might seem as though scientists just can’t make up their minds about the health effects of a salt-heavy diet, but Jacobson says the conflicting messages are a mix of junk science and industry deception. He argues that science has long confirmed that we consume too much salt, leading to unnecessarily high rates of cardiovascular disease, and his book tracks the half-century-long fight between “Big Salt” and health advocates — like himself — seeking to reduce the stuff in our food. Jacobson says it’s finally time to cut the salt in our food by one-third and act on the facts we’ve known all along.

The Saturday Evening Post: How do you defend the science you put forth in your book? Is there a scientific consensus that sodium consumption is too high?

Michael F. Jacobson: There has long been a consensus that we should reduce sodium intake to reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes. The consensus is reflected in statements from organizations like the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the World Health Organization, and the American Heart Association. These are not organizations that take risky positions or base their statements on flimsy evidence. Typically, in fact, they wait far too long to tell the public to do one thing or another.

In contrast, the “opposing side” — if you want to put it that way — has a comparative handful of studies that have been criticized for basic flaws from the day they were published. At this point, I hope that the debate over salt has ended. Last year the National Academy of Sciences issued a report that summarily dismissed those contrarian studies as being basically flawed. They dismissed them with a sentence, citing the other evidence that has long been mainstream.

SEP: You write about the “J-shaped curve” — the finding that lower salt intake also results in a high risk of cardiovascular disease — as the basis of a lot of these “contrarian” theories around salt. What do you make of the science behind it?

Jacobson: It’s junk. The PURE studies [Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology], which have been the most widely publicized as showing that consuming less salt could be harmful, are based on taking one urine sample from a number of participants at the beginning of the study. One sample. It’s not even a 24-hour collection, which is the standard for measuring sodium intake. The next assumption they make is that one sample is representative of a person’s lifetime consumption, but it’s not. Maybe that person ate out that day, or maybe they had cancer and were barely eating. People have long criticized that research, but in the last few years two studies completely debunked it.

Last year, the NAS did a report on sodium and cardiovascular disease. They did a meta-analysis of the best studies that involve 24-hour urine collections and found the expected linear relationship. They dismissed the PURE studies and others that found the J-shaped curve, as fatally flawed. I hope that ends the controversy.

A few years ago, Congress said the government shouldn’t take action to reduce sodium until the NAS did a study to look at sodium’s direct relationship to cardiovascular disease. Well, now they have done that study, concluding that lowering sodium is beneficial and not harmful.

SEP: How would you say that news media figures into the controversy around diet science like this?

Jacobson: I don’t understand why health journalists have given unwarranted credence to the PURE studies and their predecessors, because they’re so contrary to what the bulk of the research says. I think they, starting with The Washington Post and The New York Times, have been really irresponsible. Maybe it is an example of “man bites dog” to some extent. I bet editors love those stories that publicize the contrarian view, especially when the researchers are at respected institutions.

In the case of the PURE studies, they’re not tainted with industry funding. Rhetorically, it’s easier to shoot down studies that are funded by the snack food industry or something. But I’m really puzzled, and many other people in the field of hypertension and cardiovascular disease are shocked that those [PURE] researchers continue to get funding for that kind of research, and that respected publishers — like the Lancet or British Medical Journal — accept these studies. They certainly confuse the public.

The same phenomenon has taken place on a whole range of public health issues of great importance. With the lead industry — defending lead in gasoline — it goes back 100 years. Typically, it’s industry either sponsoring the research, or, if the research is independent, then ballyhooing the research that supports their views, saying, now government can’t act until we do studies that may be impossible to do.

With salt, there’s been a “moving of the goalposts.” Thirty years ago, the evidence was clear that increasing sodium intake increased blood pressure, and increased blood pressure then increased the risk of cardiovascular disease. Almost every researcher agreed then that raising salt increased the risk of cardiovascular disease, but after a couple of studies contrarians said that those conclusions couldn’t be coupled, that we had to prove directly, with randomized controlled studies, that raising sodium increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. Those studies are almost impossible to do. A few studies (I mention them in Salt Wars) provide some evidence, but they’re all limited in one way or another. But the American Heart Association and the WHO and others say that that research is totally unnecessary, they are certainly not funding the research, and we have far more evidence than we need to call for policies to reduce salt in the food supply and diet.

The thrust of the bulk of the field is to say, let’s reduce sodium throughout the food supply to “make the healthy choice the easy choice.” There are studies showing that if you start with lower-sodium foods and add salt, you’ll generally end up with less salt than what we see in most of our foods now.

SEP: You’ve been involved in health advocacy for many decades. What have you seen change in industry and policy as far as the American diet is concerned?

Jacobson: With salt, the policy battles began in 1969 when the White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health said that sodium in the food supply should be lowered. At that time, and currently, the Food and Drug Administration considers salt to be “generally recognized as safe,” and could be used in any amount. But on the basis of the existing research back in 1978, we [Center for Science in the Public Interest] petitioned the FDA to adopt regulations to lower sodium, and top researchers supported the petitions.

A few years later, the FDA in the Reagan administration was headed by a hypertension expert, and he said that we should lower sodium by taking a voluntary approach and that if industry didn’t lower sodium, he would mandate it. That commissioner left the agency after two years, and meanwhile industry did next to nothing. Then, CSPI focused on getting sodium labeling on all foods, and we helped get the nutrition labeling law passed, which mandated labeling like the Nutrition Facts labels that list sodium on all packaged foods. So we waited to see whether labeling would reduce sodium intakes, and when I looked at it 10 years later I saw that, no, it didn’t seem to have any effect. Sodium consumption stayed the same. So in 2005 we re-sued the FDA and filed a new petition. By then, the evidence was far greater that sodium boosted blood pressure. But the government did nothing. So we then succeeded in getting Congress to fund the NAS to do a study on how to lower sodium intakes.

In 2010, the NAS published a landmark report saying the FDA should mandate lower sodium levels in the food supply, but the FDA commissioner immediately said they would push again for voluntary reductions. It took a while — six years in fact — for the FDA to come up with voluntary targets for lowering sodium in packaged foods. That was in June 2016, just months before the Obama administration left office, so clearly there was not enough time to finalize those targets.

Four years later, the Trump administration still has done nothing. Absolutely nothing. Although, two years ago, the FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb — who’s been in the news about COVID-19 — said that reducing sodium is probably the single most important thing the FDA could do in the nutrition world. Unfortunately, he left office a few months later and the FDA did nothing.

It’s been 10 and a half years since the NAS called for mandatory reductions in sodium, and the last time that the CDC looked, in 2016, there had been no change in sodium intake in 30 years. At this point, I think the most we can hope for is the implementation of those voluntary targets. The FDA chose targets that would lower sodium to recommended levels — if all food manufacturers complied, which they won’t — in 10 years. In 10 years, a lot of people are going to be dying unnecessarily.

SEP: What was the Salt Institute? Would you characterize it in the same way that people think of the tobacco lobby or the oil lobby?

Jacobson: Steven Colbert said that the Salt Institute shouldn’t be confused with the Salk Institute, because the Salk Institute cures polio while the Salt Institute cures hams. That got a laugh from the audience [when Jacobson was a guest on Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report in 2010]. The Salt Institute was long a lobbying group set up by salt manufacturers, like Morton Salt and Cargill.

In the book I call it “the mouse that roared.” It was a small organization — five or six staff members and an annual budget of about three million dollars — but they were real tigers when it came to defending salt. Any time people criticized sodium levels in the food supply and recommended changes, the Salt Institute would be out there with vitriolic statements, pamphlets, interviews. They generated a large amount of press that I think contributed significantly to muddying the waters. They made much of that J-shaped curve theory, that reducing sodium dramatically could actually increase the risk of heart disease. But in March of 2019, they abruptly went out of business, and no one, to my knowledge has explained why.

SEP: Since the Salt Institute has disbanded, do you see an opening for salt regulation?

Jacobson: Well, the Salt Institute was never the real powerhouse. The major player was the mainstream food industry, including Kellogg’s, General Mills, McDonald’s — all the big companies, through their trade associations, and especially the Grocery Manufacturers Association. The industry kind of begrudgingly went along with voluntary reduction, but when the FDA proposed action, they nitpicked almost every single number in the FDA’s proposal. The butter and cheese industries wanted their products entirely dropped from the plan. Surprisingly, at the beginning of 2020, the Grocery Manufacturers changed its name [to Consumer Brands Association], changed its focus away from nutrition labeling and nutrition issues in general. The two main lobbying groups essentially withdrew from the playing field.

That certainly should make it easier for the government to take stronger action on sodium. But will it? I don’t know. Many of those big companies will lobby on their own. The snack food industry has SNAC, frozen food companies have the Frozen Food Institute, pickle makers have Pickle Packers International, restaurants are defended by the National Restaurant Association, and the meat industry has the North American Meat Institute. It’s hard to know how the disappearance of those two groups will affect things but making progress won’t be a cakewalk.

Between voluntary and mandatory approaches, the voluntary approach rewards companies that don’t do anything. I talked to one official at Kraft Foods, and he said that Kraft has tried to reduce sodium, but its competitors didn’t, so Kraft felt it had to go back and restore the salt. The advantage of mandatory regulation is that it provides a level playing field for companies that want to do the right thing.

SEP: Looking at the whole scope of the last 50 years or so, what would you say makes it so difficult for the U.S. to make and pass policy regarding dietary health?

Jacobson: It’s the power of industry. But also, much of the public sees a smaller role for government compared to countries in Europe, for example. Here, we have a culture of “rugged individualism.” There’s a feeling that people can lower their sodium intake if they want, a much more voluntary, individual approach.

In contrast, the British government, in the mid-2000s, adopted recommendations to lower sodium and backed that up with a pretty aggressive public education campaign. Then they used the bully pulpit to press industry to lower sodium. Within five years, the UK achieved a 10 to 15 percent reduction in sodium intake, compared to a goal of 33 percent reduction. But after a change in government, the new government lost interest.

Chile, Mexico, Israel, and a couple of other countries have passed laws requiring warning notices on packaging when foods are high in calories, saturated fat, sodium, or sugar. These are put on front labels and are very noticeable. In Chile, the law has been in place long enough to measure some results. There have been a significant number of products that have lower sodium, sugar, or fat content to escape those warning labels. That has been the most effective policy I know of to lower the sodium content in foods and presumably to lower sodium intake.

SEP: Have we seen better health outcomes in Chile as well?

Jacobson: It’s too early to know. Something like cardiovascular disease takes so long to show up. There are also so many other things going on in Chile that come into play.

SEP: Do we see sodium affecting communities differently in the U.S.? For instance, African-American communities?

Jacobson: African Americans seem to be more salt-sensitive than whites. They also have higher rates of hypertension. African-American women have much higher rates of obesity. So, when you couple obesity with hypertension, that’s a formula for cardiovascular disease. But every subgroup of the population ends up with hypertension. By the time Americans are in their 70s and older, 80 to 90 percent have hypertension. That’s why people should lower their sodium intake, lose weight, and avoid too much alcohol, to avoid gradually increasing blood pressure.

SEP: What would a lower sodium diet look like for a lot of people?

Jacobson: Packaged foods and restaurant foods would be lower in sodium. At restaurants, portions would even be smaller. There would be little effect on taste. Let me remind you that no one is saying that industry should eliminate all salt. Rather, it’s lowering salt as much as possible without destroying the taste of the food, and maybe replacing some of the salt with flavorful ingredients.

Using less salt is the cheapest, easiest thing to do. Another way is to replace salt with potassium salt. It doesn’t taste as salty, but it helps counteract the blood pressure-raising effect of a high-sodium diet. Companies can also add more real ingredients and herbs and spices. For home chefs, McCormick, Chef Paul Prudhomme, and Mrs. Dash sell salt-free seasonings. The classic study is the DASH-sodium study. It’s a randomized controlled study — the best you can do — done by researchers at Harvard, Johns Hopkins, and elsewhere. They lowered sodium by one third, from 3,400 mg, the current average daily intake, to 2,300 mg, the recommended intake, and they found that people consuming the 2,300-mg level of sodium liked the food even more than the higher level! So, I think concerns about taste are completely overblown. People quickly get accustomed to less-salty foods.

SEP: What are some personal decisions that people can make to decrease their sodium intake?

Jacobson: Sodium levels in the food supply will not drop to healthy levels instantly, no matter what the FDA does. In the meantime, consumers have to protect their health. When you’re eating processed foods, you should compare labels, because there is wide variation among different brands of the same or similar foods. Swiss cheese has one-fifth or less of the sodium in American cheese, and you can make a perfectly good sandwich with Swiss cheese. For that sandwich, you can also choose a lower-sodium bread. Bread, because we consume so much of it, turns out to be one of the major sources of sodium. You can make lots of modest changes to achieve major reductions in sodium.

We should also be cooking more natural ingredients from scratch. That invariably results in lower-sodium foods, because we’re controlling the salt. The third thing is to eat out less often. Restaurant foods have huge amounts of sodium, especially table-service restaurants like IHOP or Chili’s. That’s partly because the portions are enormous. The more food you eat, the more sodium you consume. From a chef’s point of view, the two magical ingredients are salt and butter. And it’s not just chain restaurants. Chefs have generally not been trained to lower sodium. The best thing you could do is to cook at home from scratch using lower-sodium recipes.

I mentioned how some companies are using potassium salt, and consumers can use it too. Look for “lite salt” at the supermarket. Morton and other companies sell this, and half of the table salt has been replaced by potassium salt, so you automatically cut back when you’re cooking or sprinkle it on your meal.

SEP: Looking back at the last year of presidential debates, moderators always ask a question about the biggest issue facing Americans, and I’ve never heard a candidate say that it’s salt. So, what would you say to people who think we have bigger problems and salt just isn’t that important?

Jacobson: We do have other pressing problems. Tobacco is killing a lot more people than salt. But high-sodium diets are killing tens of thousands of people each year. Health economists and epidemiologists estimate that if we can cut our sodium intake by one-third to one-half, that would prevent 50,000 to 100,000 premature deaths every year. We’re seeing the same thing around the world, where high-sodium diets are causing more than one million deaths a year. I see salty diets as the cause of a pandemic.

We have to deal with COVID-19, that’s the immediate pandemic. High-sodium diets are harmful over a longer time frame. But our society really needs to take these problems seriously even though the deaths are not immediately linked to the cause. An airplane crash kills 300 people and that gets a lot of attention, and it should. But with public health crises, where deaths are less easily associated with the cause, solving the problem is easily postponed, especially when industry stands to gain by not solving the problem. High-salt diets are absolutely something that political leaders need to address.

Featured image: © 2020 The MIT Press, Photo by Chris Kleponis

How Salt Made Our IQs Go Up

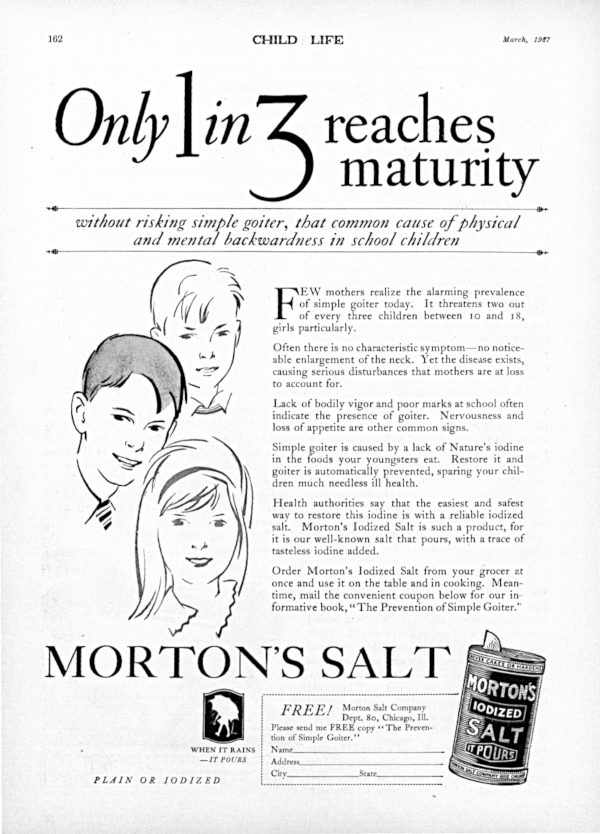

Morton Salt has long been known for its famous logo featuring the iconic “umbrella girl” — dressed all in yellow and walking in the rain as salt pours freely from a container of Morton’s — over the phrase “When It Rains, It Pours.”

She first appeared in 1914, in the days when table salt tended to clump up when exposed to humidity. The problem was solved by the Morton Salt Company when it added magnesium carbonate, an absorbing agent, to its product. The new salt would flow freely in even the most humid weather.

But Morton introduced a more important innovation in 1924. Scientists had discovered that common thyroid disorders could be remedied with iodine. People in the Great Lakes region and the Pacific Northwest, which had too little iodine in the ecosystem, were prone to developing enlarged thyroids, or goiters. Iodine shortage also affected the brain, leading to difficulty in learning or remembering.

Readers might have thought the 1927 ad was overstating the benefits of iodized salt. But the incidence of goiters dropped significantly after iodization, and the average IQ rose 15 points in areas where iodized salt had been introduced, and 3.5 points nationally.

This article is featured in the May/June 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Your Weekly Checkup: A New Study on Salt and Health

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

I don’t use a lot salt, either in cooking or on my food. My one exception is steak. A prime New York strip medium rare without salt to me is like a rose without a smell or a soda pop without a fizz. The salt makes a good taste even better.

The World Health Organization contends that most people consume too much salt, on average 9-12 grams per day or around twice the recommended maximum level of 5 grams per day. They estimate that 2.5 million deaths could be prevented annually if global salt consumption were reduced to the recommended level. They assume the salt reduction would lower blood pressure which in turn would reduce cardiovascular risk. They state that high sodium consumption ( greater than 2 grams of sodium per day, equivalent to about 5 grams of salt per day) and insufficient potassium intake (less than 3.5 grams per day) contribute to high blood pressure and increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Is this true? Should I switch to a low salt diet, deny myself the pleasures of a salted steak, to lower my risk of heart attack or stroke? After all salt (sodium) is an essential dietary nutrient.

Based on data from a recent study, the answer is no.

These investigators decided to test the WHO unproven assumption in the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study of 95,767 participants (aged 35 – 70 years) in 369 communities across 18 countries whose blood pressure was analyzed. They also analyzed cardiovascular events in 82,544 participants in 255 communities. They collected a morning fasting midstream urine sample to calculate 24-hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion, and these values were used as surrogates of intake. Participants were followed at 3, 6, and 9 years (median, 8.1 years).

The mean sodium intake (sodium, not salt; the latter would be about double that value) across all 369 communities was 4.77 grams per day, higher in China than in other countries (5.58 grams per day vs 4.45 grams per day). Blood pressure increased with greater sodium intake and was associated with an increased stroke rate in China compared to other countries. Heart attacks and mortality did not increase and in fact, higher sodium intake was actually associated with lower rates of heart attack and total mortality.

PURE noted that higher potassium intake found in fruit, vegetables, dairy products and nuts was associated with reduced risk of stroke and heart attack mortality and could counter potential harmful effects of excess salt intake.

The take home message from this observational study is that that both blood pressure and stroke increase with greater salt intake, but heart attack and mortality do not. If your blood pressure is normal, there seems little reason to restrict salt intake (but don’t go crazy) as an isolated public health change and that the current salt intake in the U.S. population seems acceptable. However, if your blood pressure is high, and not brought down to normal levels by appropriate medications, salt intake should be restricted. High quality foods with increased potassium content appear to be protective and such intake should be encouraged, especially for those with elevated blood pressure.

I will continue to salt my steak and maybe my morning scrambled eggs as well.

How to Cook a Muskrat and Other Wild Dishes from 1938

Squirrel potpie? Old news according to 1938 Country Gentleman author Jim Emmett, who was on the hunt for more unusual home-cooked fare. Stuffed raccoon, parboiled porcupine, and opossum roasting over an open fire were just a few of his tasty finds. Plus, a tip for foraged edibles: Fried or drizzled, wild greens go down best with butter.

A note to the 21st-century chef: Take these dishes with a grain of salt. Food safety has changed some in the 80 years since these recipes were published. To know what’s safe to eat — and, more importantly, what isn’t — in your area, seek out local wildlife and foraging experts.

Savory Dishes from the Wild

Originally published in The Country Gentleman, March 1938

Your ancestors, or mine, may not have endured Plymouth winters, trekked Midwest plains, or even been born in this country; still, there is a good bit of the pioneer in the make-up of most Americans. A joint of venison sent to the house is eagerly enthused over, we cook precious wild ducks and upland game birds with fear in our hearts that they may be spoiled in the oven, and even prepare potpies of squirrel or rabbit more carefully than we do expensive cuts of meat.

The eating of only certain wild animals is a habit passed down from days not so far back when a farmer stepped outside his door to shoot a deer nibbling apples from the tree he cared for so carefully. Naturally, with game so plentiful nothing but the best graced his table. Fat bear and young deer not only butchered quickly but yielded a large supply of good meat at the expense of a single charge of expensive powder and precious ball. Canvasbacks and mallards were preferred when the waters of every inland pond blackened at dusk with southbound birds, and trout from the pasture brook which appeared on the breakfast table then would be entered in fish contests now.

This preference for certain wild game seems also to be a matter of location. For instance, in the North, muskrat haunches are considered a delicacy by most French-Canadian families, and in the South, opossum is enthused over on the plantation owner’s table. Frog legs are preferred to chicken drumsticks in the Adirondacks, while on many a Tidewater-Maryland farm eels are a greater favorite than the oysters, crabs, and fish lying off the wharf for the taking.

How to Pluck a Possum

The possum is more than an animal in the South; he is a distinctly American institution, and there the term opossum is considered an affectation. Many Northerners think of the possum as being eaten only by the plantation help. But those fortunate enough to sample the famed hospitality of the South, as it flourishes in rural regions, find that possum and sweet potatoes is also big-house fare. The chief difference is that the white folk bake theirs in an oven, while rural African Americans so often cook on the hearth with an open fire, suspending the possum on a wet string before a high bed of hickory coals. The twisting and untwisting string rotates the meat which is basted with a sauce of red pepper, salt, and vinegar. After having eaten possum cooked both ways, I prefer the open-fire method.

There are two golden rules to possum cooking: First, he is good only in freezing weather; secondly, do not serve without sweet potatoes. Preparation is not difficult, but like all wild things must fit the particular animal. Stick the possum and hang overnight to bleed. Next morning fill a tub with hot water, not quite scalding, and drop the possum in, holding tight to his tail for a short time so the hair will strip. It is then an easy matter to lay him on a plank and pull out all the hairs somewhat as one would pluck a chicken. After drawing, he should be hung up to freeze for two or three nights.

As a preliminary to cooking, place him in a five-gallon kettle of cold water into which has been thrown a couple of red-pepper pods, if you have them, otherwise a quantity of ground pepper. Remove after an hour of parboiling in this pepper water, throw water out, and refill kettle with fresh water, in which he should be boiled another hour.

While all this is going on, the sweet potatoes should be sliced and steamed. Take the possum out of the water, place in a large covered baking pan, sprinkle with black pepper, salt, and sage, and pack the sweet potatoes lovingly about him. Pour a pint of water in the pan, put the cover on, and bake slowly until brown and crisp. Serve hot, with plenty of brown gravy.

Haunch of Muskrat with Watercress

Muskrat haunches, usually with watercress, grace the French-Canadian farmer’s table often enough to guarantee their value as a worthwhile game dish.

Muskrats must be skinned carefully in order not to rupture the musk or gall sacks; those offered for sale on city markets are a trapper’s byproduct; often indifferent skinning spoils them for cooking. French-Canadians use only the hind legs or saddle, four animals for two servings. After a careful washing, they are placed in a pot with some water, a little julienne or fresh vegetables, some pepper and salt, and possibly a few slices of bacon or pork. After simmering slowly until half done, they are removed to a covered baking pan, the water from the pot is put in with them and baking continued with frequent basting until done.

In Maryland and Virginia, the muskrat is known as marsh rabbit and valued highly as a game dish. Cooks there use the entire animal, soaking it in water a day and night before cooking. Then follows 15 minutes’ parboiling, after which the animal is cut up and the water changed. An onion is added, with red pepper and salt to taste, and a small quantity of fat meat. Just enough water is used to keep from burning, thickening added to make gravy, and cooking continued until very tender.

Trade Thanksgiving Turkey for Roasted and Stuffed Raccoon

Coon is excellent eating if caught in cold weather. In skinning, be careful to remove the kernels or scent glands, not only under each front leg but also on either side of the spine in the small of the back. All fat should be stripped off. Wash in cold water, then parboil in one or two waters; the latter if age warrants. Roasting should continue to a delicate brown. Serve fried sweet potatoes with the meat. The coon, with its reputation of washing even its vegetable diet before eating, is one of our cleanest animals; he will not fail you as a cold-weather game dish if you observe the skinning precaution.

Parboiled Porcupine

In the North Woods the porcupine is a lost hunter’s stand-by, his emergency food supply. But unlike most emergency rations this inoffensive little animal is excellent eating, especially if young, when his flesh is as juicy and as fine flavored as spring lamb. The secret of skinning is to commence at the belly, which is free of quills; start the skin there and it pulls off as easily as that of a rabbit. Parboil for 30 minutes, after which roast to a rich brown or quarter for frying or stewing.

Fowl Cooking

The lower grades of ducks are acceptable eating if correctly prepared for cooking. All waterfowl, even the better ducks, have two large oil glands in their tail, put there by Nature to dress the bird’s feathers; these should always be removed before cooking.

The breasts of coot, rail, and young bittern are always worth serving. Cut slits in the removed breasts and in these stick slices of fat salt pork, then cook in a dripping pan in a hot oven. The rank taste of even fish ducks can be neutralized, unless very strong, by baking an onion inside and using plenty of pepper inside and out.

The meat fibers of all game birds and animals are fine grained, containing very little fat, even though the muscles themselves may be encased in it. For this reason most game recipes mention larding. This consists of laying strips of fat pork or bacon not only on top of the meat, but inserting them in slits cut in the flesh itself to prevent dryness. As a rule, dark-meated game should be cooked rare, so red juices, not blood, flow in carving. White-meated game should be thoroughly cooked. Animals and birds, tough or old, should be parboiled first; such meats are better stewed.

The Way with Turtles

Aquatic turtles are good eating at any time, old guides claiming their flesh has medicinal value. The common snapper is excellent, and preparing is not difficult. Aside from any humanitarian feeling, I do not like the method of dropping the live turtle into a tub of scalding hot water; I prefer to get that wicked head off as quickly as possible. One must carry the brute by its stocky tail well away from flapping trousers. Another man with an ax in one hand and a stick in the other extends the stick atop a convenient log. Hold the turtle near and snap go its jaws over the stick with a grip which never fails to make one realize what it would do to a foot or hand. With its neck extended, down comes the ax. One need have no qualms of pity when dealing with this enemy to wildlife.

After letting the turtle bleed, drop in scalding water, when the outside of the shell will drop right off and the skin can be easily removed. Then cut the supports of the flat undershell and remove it entirely, so the turtle can be easily cleaned. To save cutting the meat out, boil in its cleaned shell a short time, when the meat will drop off. Cut up, boil slowly three hours with chopped onion, or stew with diced salt pork and vegetables.

Freshwater Finds: Catfish, Carp, Eels, and Frogs

Proper preparation makes even our so-called coarse fish good eating. To skin bullheads or catfish, cut off the ends of sharp spines, split the skin behind and around the head, and from this point along back to the tail, cutting around back fin. Then peel two corners of the skin well down, cut backbone and hold skin in one hand while the other pulls the body free.

Carp should be carefully skinned rather than scalded. There is a layer of fat or mud between two skins and only with this removed will the fish be found good eating. Many people condemn catfish and carp as being soft fleshed; which they are if taken from too warm water. But every fish is better caught out of cold water.

Eels can be easily skinned by nailing through the tail at a convenient height. Cut the skin around the body, just forward of the tail, work edges loose, then pull down to strip off the entire skin. To broil, clean well with salt to remove slime, slit down back and take out bone, then cut in 2-inch pieces. Rub these with egg, roll in cracker crumbs or corn meal, season with salt and pepper and broil to a nice brown. To stew, cut in pieces after removing the bone, cover with water in a stewpan, and add a teaspoon of vinegar. Cover the pan and boil half an hour, then remove, pour off water and drain, add fresh water and vinegar as before and stew until tender. Finally drain again, add cream for a stew, season with salt and pepper only, and boil a few minutes to serve hot.

Smothered catfish is beloved [in the South], utilize this ugly but sweet-fleshed fish to advantage. Place a large skinned catfish in the baking pan and slice onions to put on top along with strips of bacon. Sift flour lightly over all, salt and pepper, and place in a heated oven 15 minutes.

Frog’s legs are a delicacy from the first spring days until freeze-up time. The northwoods hunting-camp cook soaks the hind legs an hour in cold water, to which vinegar has been added, as a preliminary to cooking. He then drains, wipes dry, and places them in a skillet of bubbling hot cooking oil. Some Southern tidewater shooting-camp cooks use the entire frog, other than the head; others grill the legs only. A preparation is made of three tablespoons of melted butter, half a teaspoon of salt, and a pinch of pepper. The body or the legs are dipped in this, rolled in crumbs and broiled three minutes each side.

Foraging Plants from Field and Woods

Not to be outdone, our early spring pastures and fields offer many edible greens free for the gathering. Dandelion greens, with a piece of bacon, are still regarded by many as a sure sign of spring. Milkweed shoots, wild mustard, dandelions, dock, and sorrel should be dried immediately after washing, then boiled with salt pork, bacon, or other meat. If on the old side, parboil first in water to which a little soda has been added, then drain before boiling again in plain salted water.

Perhaps you have cooked these wild things and not been satisfied with the results. Try chopping the boiled greens fine, then putting in a hot frying pan with butter, pepper, and salt, and stirring until thoroughly heated.

The tender stems of young brake or bracken [fern], cooked same as asparagus, are equally as good as that much-sought-after vegetable. The plants should not be over 4 inches high when they will show but a few tufts of leaves at the top; if much older they are unwholesome. Wash the stalks, scrape, and lay in cold water for an hour. Then tie loosely in bundles and put in a kettle of boiling water to boil three quarters of an hour, when they should be tender. Drained, laid on buttered toast, dusted with pepper and salt, and covered with melted butter they are as good as asparagus, some claim even better.

Wilted dandelion greens call for a peck of fresh tops and half a dozen strips of bacon. Fry the bacon until crisp, then crack into small pieces and pour with drippings over the washed leaves.

Botanists tell us over a hundred edible plants grow wild in our fields and woods. While we may find it easier to raise cultivated vegetables than to gather wild things, it is good to know we live where Nature offers this wholesome fare.