Destino: When Disney Met Dalí

Imagine unearthing a Picasso in the corner of your basement, perfectly preserved for decades before you finally uncover it. Roy E. Disney experienced this in 1999 when he stumbled across Destino, the 1946 collaboration between his uncle Walt Disney, the animation pioneer, and Salvador Dalí, Spain’s legendary surrealist painter. And his decision to revive the project left us one of the most interesting collaborations in animated film history.

How many stars had to align before Disney’s creativity and Dalí’s imagination finally came together? It turns out, all they really needed was a dinner party hosted by Jack Warner (of Warner Bros. Studios). Walt Disney had caught the surrealism “bug” while creating Fantasia, and with it came the desire to continue dabbling in projects that carried the same dreamy element. Similarly, Dalí had a newfound fascination with cinematography and was determined to become the first popular surrealist to invade the film industry.

The story of their initial meeting has been passed around like folklore. It could only be verified through John Hench’s recollections and Jack Warner’s guest list. As the legend goes, at Warner’s party, Dalí and Disney immediately connected, and an overjoyed Dalí accepted Disney’s proposal to collaborate on a surrealist animated short. Over the next eight months, they created more than 200 storyboard sketches set to a love ballad composed by Fantasia composer Armando Dominguez. Their paired ambition (along with John Hench’s tremendous draftsmanship) resulted in the story of a haunting romance between two star-crossed lovers: Dahlia, a mortal woman struggling to find love, and Chronos, an all-powerful titan and the personification of time itself.

Sadly, financial struggles after World War II forced the studio to place the project on an indefinite hiatus. Destino spent the next five decades hidden in the Disney archives.

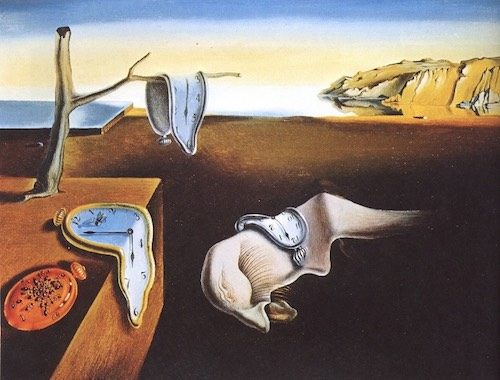

Destino was a project shared between two great artists at the peak of their powers. Dalí and Disney strove to bring people out of their daily tedium into what they considered better, more imaginative worlds. In their six-and-a-half-minute film, objects around Dahlia break or melt away as she dances her way through the scenery. She moves in and out of landscapes like a trapeze artist while her large, longing eyes scan the terrain for her lover. Her body undergoes drastic transformations — taking the shape of a bell tower, a dandelion, a ballerina, and a baseball — all in hopes of finding a form that can coincide with Chronos’s immortality. In turn, Chronos tries to meet her efforts by breaking free from his bonds.

But large towers prevent them from reaching each other. It takes a variety of surreal movements and shifting scenery before Dahlia’s bell tower appears in the hole in Chronos’s heart, signifying that the two have finally become one.

It took nearly 60 years for Destino to finally be completed — 37 years after Walt Disney’s death and 13 years after Dalí’s. By the time the artwork was rediscovered, nearly 50 original sketches had been lost or damaged due to poor preservation. Roy Disney re-recruited John Hench to help revive the project in 2002, and together, they stitched the remaining sketches into a single piece, keeping as close to the original storyboard as they could. Fans of Disney and Dalí will find that both artists’ styles are clearly evident throughout the film.

The final product was released on June 2, 2003, at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival. It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film and honored in multiple exhibitions. It won titles in the Chicago, Rhode Island, and Melbourne International Film Festivals and even inspired its own four-star resort in Talamanca, Spain.

Disney and Dalí got more than what they bargained for out of their partnership. The Destino collaboration led to a lifelong friendship between the man behind the mouse and the painter of melted clocks. It’s more than just a surrealist 1946 package film. It’s a melding of the styles of two of the 20th century’s most imaginative minds.

The Art of the Post: Rockwell Goes to War

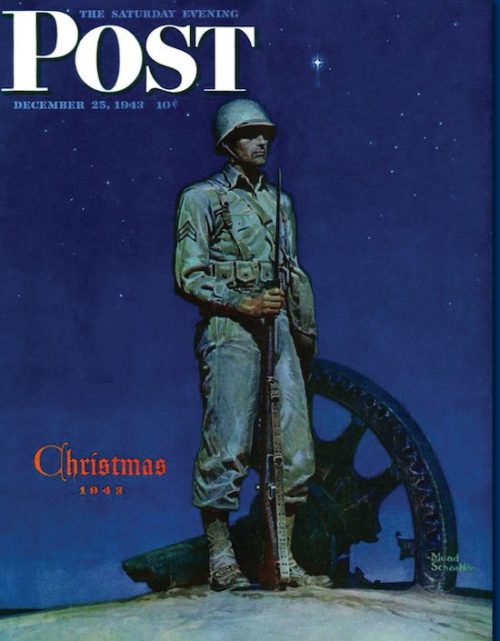

During World War II, two Saturday Evening Post illustrators, Norman Rockwell and Mead Schaeffer, wanted to aid their country’s war effort. They were too old to enlist, and neither one was physically suited to be a fighter, but they felt they might be able to help with their art.

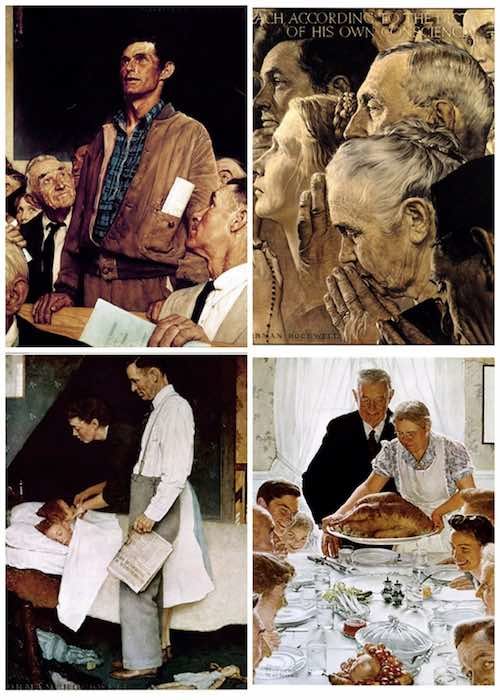

The two artists decided to paint patriotic pictures and offer them free to the Department of Defense for fundraising and enlistment campaigns. They worked hard developing their preliminary drawings; Rockwell decided to illustrate Franklin Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” while Schaeffer chose a series of military themes. When they finished mapping out their ideas, the two took the long train ride from their studios in Vermont to the U.S. Office of War Information in Washington, D.C. The illustrators excitedly showed their proposals but met a frosty reception.

The Assistant Director of the Office was Archibald MacLeish, a famed poet, future Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright, and proud intellectual who didn’t think much of illustration. Rockwell recalled being told, “The last war you illustrators did the posters. This war we’re going to use fine arts men, real artists.” MacLeish thought the military should use artists such as Salvador Dalí, Marc Chagall, and Stuart Davis to inspire the American public.

The Pentagon was not totally unsympathetic to Rockwell and Schaeffer. According to Rockwell’s autobiography, it offered them a consolation prize: “If you want to make a contribution to the war effort, you can do…pen-and-ink drawings for the Marine Corps calisthenics manual.”

Stung, the two illustrators took the long, depressing train ride home to Vermont. Schaeffer’s family recalls that when Schaeffer’s wife learned of the rejection, she spoke up: “To heck with the Army, why don’t you offer your pictures to the Post instead?”

The illustrators turned around and took the train back down to the Post’s offices in Philadelphia. There, editors reviewed the preliminary drawings and agreed to run Rockwell’s paintings as internal illustrations, followed by Schaeffer’s paintings in later issues.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms quickly became a national phenomenon. The Post received 60,000 letters about them. As editor Ben Hibbs later wrote:

The results astonished us all. … Requests to reprint flooded in from other publications. Various government agencies and private organizations made millions of reprints and distributed them not only in this country but all over the world. [Rockwell’s] four pictures quickly became the best known and most appreciated paintings of that era. They appeared right at a time when the war was going against us on the battle fronts, and the American people needed the inspirational message which they conveyed so forcefully and so beautifully.

It began to occur to government officials that they might have made a mistake rejecting the paintings. Belatedly, they tried to jump on the bandwagon. With Rockwell’s permission, the Treasury Department took the Four Freedoms on a tour of the nation as the centerpiece of a Post art show to sell war bonds. The paintings were viewed by 1,222,000 people in 16 cities and were instrumental in selling $132,992,539 worth of bonds.

The illustrations proved far more effective than anything else the government had planned. The Pentagon even sent a film crew to Vermont to stage a documentary about the illustrations, implying (falsely) that Rockwell and Schaeffer had been working at the behest of the government all along.

As for MacLeish, he did not last long in his job. Rarely has a misguided act of cultural arrogance been so promptly, resoundingly, and satisfyingly refuted.