The Great War: November 28, 1914

In the November 28, 1914, issue: German army cooks scoop up war medals and journalists fight censorship and military officers for the truth.

Three Generals and a Cook

By Irvin S. Cobb

Still observing the war from the German side, Cobb spent a week socializing with high-ranking officers in the Kaiser’s army. He was particularly impressed by a common soldier who had earned the Iron Cross decoration. Cobb was even more surprised that the medal had been awarded to a cook.

“While the officer rattled the steel lids the cook himself stood rigidly alongside, with his fingers touching the seams of his trousers. Seen by the glare of his own fire he seemed a clod, fit only to make soups and feed a fire box. But by that same flickery light I saw … on the breast of his grease-spattered gray blouse … a black-and-white ribbon with a black-and-white Maltese cross fastened to it. I marveled that a company cook should wear the Iron Cross of the second class and I asked the captain about it. He laughed at the wonder that was evident in my tones.

“‘If you will look more closely,’ he said, ‘you will see that a good many of our cooks already have won the Iron Cross since this war began, and a good many others will yet win it — if they live. We have no braver men in our army than these fellows. They go into the trenches at least twice a day, under the hottest fire sometimes, to carry hot coffee and hot food to the soldiers who fight. A good many of them have already been killed.

“‘Only the other day … two of our cooks at daybreak went so far forward with their wagon that they were almost inside the enemy’s lines. Sixteen bewildered Frenchmen who had got separated from their company … thought the cook wagon with its short smoke funnel and its steel fire box was a new kind of machine gun, and they threw down their guns and surrendered. The two cooks brought their 16 prisoners back to our lines too, but first one of them stood guard over the Frenchmen while the other carried the breakfast coffee to the men who had been all night in the trenches. They are good men, those cooks!’”

“I am in doubt as to which of two men most fitly typifies the spirit of the German Army in this war — the general feeding his men by thousands into the maw of destruction because it is an order, or the pot-wrestling private soldier, the camp cook, going to death with a coffee boiler in his hands — because it is an order.”

The Private War

By Samuel G. Blythe

In modern times, we expect wars to generate a steady stream of new reports from the front lines. But 100 years ago, the military reduced the news stream to a trickle. Every reporter’s dispatch was rigorously censored to remove any information that might aid the enemy or make the military command look bad. And, as Blythe reports, the British and French armies devised several diversions to prevent reporters from reaching the front.

“[British Field Marshall] Kitchener does not recognize any right the public may have to information. … It is Kitchener’s unshakable opinion that all the news the British need; or should have, concerning the war is comprised in the line: Your King and Your Country Need You! And that is all the British people would get if he could put it over. However, powerful as he is, he is not powerful enough for that; and a few words have occasionally leaked out that were not contained in the official bulletins. The output has been small, however, considering the tremendous size of the conflict. …

“Greatly to the astonishment of the British War Office, it was learned that General Joffre, in command of the French troops, strenuously objected to the presence of the English correspondents. It was all very astonishing and very perplexing and very embarrassing. …

“[Some of the more impatient correspondents asked General Joffre about his objections.] ‘Objections?’ was the polite reply. ‘Why, there are no objections on our part, save as we object out of courtesy to, our ally, Great Britain. France will be very happy to have these correspondents with the army; but naturally, if the British authorities think it wiser not to allow them at the front we can do nothing but bow to that decision.’”

“Whereupon the situation became reasonably clear. The British War Office was using the French as the obstacle, and the French were doing the same thing with the British. It was a simple and efficacious case of passing the buck.

“And so it goes. The Press Bureau is press-bureauing; the censors are censoring; and Kitchener, on the British side, and Joffre, on the French side, are seeing to it that not a word is printed about this war which they do not desire to have printed.”

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

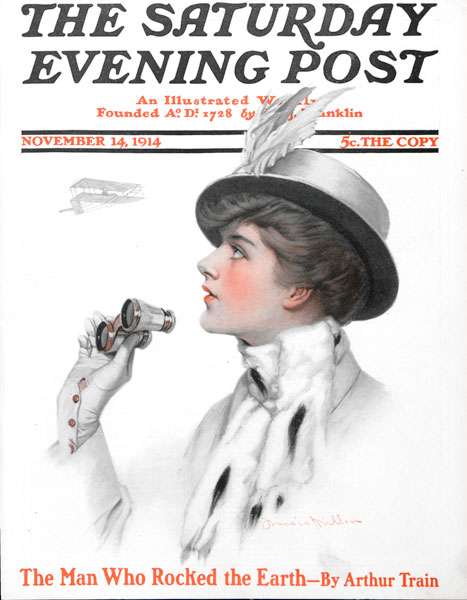

The Great War: November 14, 1914

In the November 14, 1914, issue: Canada goes to war, Great Britain looks for a new theme song, and a journalist downplays the atrocities of a nation invaded.

Booked Through for the Empire

By Maude Redford Warren

Over in Canada, the war enjoyed just as much support as in England, according to Warren. She wrote about the men she saw in an Ottawa parade of Canadian recruits. Their faces, she wrote, clearly showed“love for the Empire, the loyal urge that makes even a cheap soul worth while and that books their bodies through to the end, whatever it be, so it be for the good of the empire.”

But it wasn’t all flag-waving and happy parade. The author spoke with an elderly woman who had been walking alongside the recruits, among [whom/them] was her grandson. The woman spoke of the price she had paid to uphold the British Empire, and all the wars that were supposed to be the last.

“‘It seems to me now that that’s been my whole life — watching men march away. For when I was a little girl in Kingston I saw my father go to the Crimea and I had no more sense than to laugh and clap at the music and the flags. He never came back, and the comfort they offered my mother was that there never would be another war.

“‘My husband went with Gordon to Khartoum when I was a young bride, and though he came back to me he was never a well man. When I had to do his work and mine — not that I wasn’t willing, but it’s hard when a woman has children — the comfort he gave me was that the world was too wise now to have any more wars, except maybe in savage places.

“‘My youngest son went to South Africa, but I wouldn’t go to see him off; he never came back, and they said then that one proof that war was dying out was that England was so ill-prepared to carry through that one.

“Now my eldest son’s only son has gone with the artillery — the only one that could carry on our name. He is sailing down the St. Lawrence now, and maybe it’s true this time that this will be the last war, and maybe it’s not.’

“‘You didn’t try to hold them back?’ one ventures.

“‘No, though I’d never have asked them to go. If a man sees his duty to his country in that way it’s a woman’s place to do her share for the country too. I’m glad I’m a British subject, but there is surely no harm in saying that any woman is lucky who belongs to a country that doesn’t ask her for the lives of her men.’”

Vox Populi

By Samuel G. Blythe

The Briton spirit was just as determined and confident as the German, Blythe reported.

“There is no doubt that Great Britain is loyally and patriotically and unitedly in this enterprise, albeit there is a vast British population that does not yet appreciate the graveness of the dangers that threaten their land. Those who understand are loyal, and those who understand but partially are loyal also, so far as their understanding goes.

“‘This war,’ said [Home Secretary Reginald] McKenna, ‘was not of our seeking, but became our duty. Our case is clear, clean and perfect. It will be so held in the eyes of the world and so recorded in history. Therefore, we must win; and we shall win! There is no doubt of that.’

“‘We didn’t want to go to war,’ said the gardener at Sidcup, ‘but we had to go. Being Britons, we couldn’t do anything else. Now that we have gone to war, we’ll win!’

“Of all the men I talked to that Sunday afternoon there was not one who grumbled over the war, complained about it, bewailed his own hard luck — most of them had been hit one way or another — or expressed any but the most absolute conviction that Great Britain will win the war, and that the German Empire is to be eliminated. I did not find any whiners or any grumblers, or anything but a sort of stolid, philosophical view.”

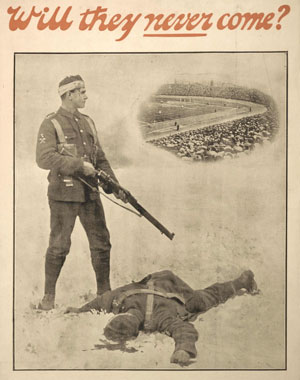

One of the most discouraging war songs ever written appeared in Great Britain during these months. It was titled, “Your King and Country Need You!”

“This is sung nightly in every music hall and moving-picture show, and is more of a wail than an inciter to gallant deeds of arms.Here is the chorus, which is in slow march time, as the music says, and which the audience are invited to chant slowly with soloists:

“Oh, we don’t want to lose you, but we think you ought to go,

For your King and country both need you so.

We shall want you miss you; but with all our might and main,

We shall cheer you, thank you, kiss you, when you come back again.

“In order that the proprieties may be observed the author supplies a footnote, starred on the word kiss, which says: ‘When used by male voices substitute the word bless for kiss.’

Listen to “Your King and Country Need You!”, recorded by Helen Clark in 1914

Punitives Versus Primitives

By Irvin S. Cobb

Two weeks earlier, Cobb had brought up the topic of wartime atrocities: Germans slaughtering Belgians, and Belgians ambushing, poisoning, and torturing Germans. In this issue he reported on his investigation into the truth behind the rumors.

“From Belgian, from French, and from English sources I have had hundreds of tales of barbarities by Germans. From German sources I have had hundreds of tales of barbarities by Belgians, Russians, French and British — but particularly by Belgians. My deliberate personal opinion is that 80 percent of the stories are absolutely untrue.”

Cobb was, at the time of his writing, visiting the German side of the Western Front as a guest of the German army. For this reason, perhaps, he seems to have been quite sympathetic to their claims of innocence.

“I have found extended areas in Belgium through which hundreds of thousands of German soldiers had passed without signs of wanton damage of any sort — districts where the houses were all intact, the crops untrampled, and the fruit left hanging on the trees, and not so much as a window smashed or a haystack toppled over.”

He even seems to accept, with a regretful shrug, the Germans’ execution of a young Belgian woman. He heard the story from a German doctor in the border town of Aachen.

“During the investment and bombardment of the Liege defenses, a battery of German siege guns was mounted in the village of Dolhain. … From the accuracy with which shots from the Liege forts fell among them the Germans speedily became convinced that someone in the village was secretly communicating with the defending fortresses, telling the gunners there when a shell overshot the German lines or fell short. …

“A young girl, the daughter of a well-to-do citizen, was using a telephone that through some oversight the Germans had failed to destroy. From the window of her father’s house she watched the effect of the Belgian shells, and after each discharge she would call the fort in Liege and direct the batteries there how to aim the next time.

“For days she had been risking her life to do this service for her country. She was detected, tried by court-martial, convicted of violating the articles of warfare by giving aid to the enemy, and condemned to be shot. Next morning this girl, blindfolded and with her arms bound behind her, faced a firing squad. As I conceive it, no more heroic figure will be produced in this war than that Belgian girl, whose name the world may never know.

“‘I do not know how the American people will view the execution of military law on that brave young woman,’

said my informant. ‘I do know that the officers who tried her sorely regretted that, under their oaths to do their duty without being influenced by sentiment or by their natural sympathies, they sentenced her to death. They could do nothing else. She had been instrumental in causing the killing and wounding of many of our men. By the rules of war she had risked her life, and she lost it. Our troops … had no right and no power to spare the girl who, over the telephone, directed the fire of our enemies. But if I were a Belgian I would give my last cent to rear a monument to her memory.’”

Cobb never seems to think it outrageous that a young woman helping her country defend itself against an invading army should be executed as a spy or traitor. Yes, the monument idea was a nice touch, but it was a romantic gesture that saved no one’s life. There would be many more before the war ended.

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

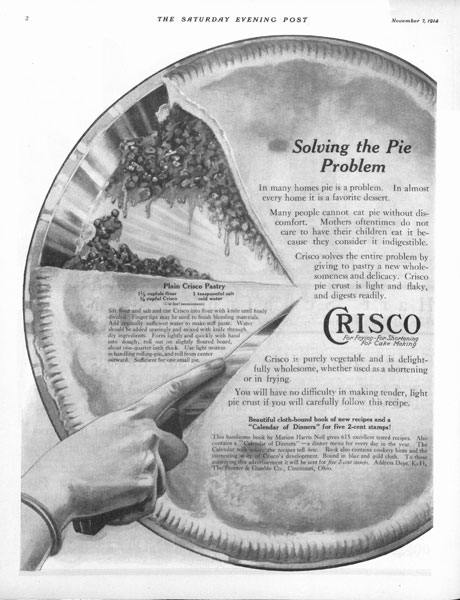

The Great War: November 7, 1914

In the November 7, 1914, issue: U-boats put an end to British chivalry, and the Germans offer up some shockingly bad predictions of the war’s end.

The Toll

By Samuel G. Blythe

Four months into the conflict, there were signs that this war was going to be different. Modern technology enabled armies to cause more destruction than ever before. The belief that this would be the ultimate, decisive war encouraged them to use the technology with little regard for restraint. As Blythe noted, German U-boats were already making chivalry a fatal indulgence.

“Perhaps you remember that order made by the British Admiralty a day or so after the three British cruisers were sunk by a German submarine or submarines. …

“When the first of the three ships … was hit by a torpedo and began to sink, the two other ships closed in to help her and to pick up her men who were struggling in the water. They were torpedoed and they sank too.

“Some days after the news came the Admiralty published an order to all ships in the British Navy. …They were instructed that … the commanders of all ships are to look out for their own ships and for their own men, and let the other ships do the same. … When a ship, lying near other ships, is torpedoed, that ship must sink, and that must be the end of it. Because two other captains rushed in to help another ship, three ships were lost instead of one. The humaneness of it amounts to nothing. The heroism of it is nil.”

The Grapes of Wrath

By Irvin S. Cobb

Despite signs that there would be less humane, more deadly war than any before, there was no shortage of enthusiasm for the fight. In Germany, Cobb found only eagerness for battle and confidence in victory. He illustrated the popular spirit with an anecdote that sounds like the set-up to a joke. Three Germans walk into a café — a business man, a scientist, and an army officer — and strike up a conversation about the war with Cobb.

“The business man says, ‘In six weeks from now we shall have beaten France; in six months we shall have driven Russia to cover. For England it will take a year — perhaps longer. And then, as in all games, big and little, the losers will pay. France will be made to pay an indemnity from which she will never recover. Of Belgium I think we shall take a slice of seacoast. … Russia will be so crippled that no longer will the Muscovite peril threaten Europe. Great Britain we shall crush utterly. She shall be shorn of her navy and she shall lose her colonies. … She will become a third-class power and she will stay a third-class power.’

“The scientist spoke next … ‘This war was inevitable. Germany had to expand or be suffocated. And out of this war good will come for all the world, especially for Europe. We Germans are the most industrious, the most earnest, and the best-educated race on this side of the ocean. Under German influence illiteracy will disappear. … And after this war — if we Germans win it — there will never be another universal war.

“The soldier spoke last … ‘War was forced on us by these other powers. … But when war came we were ready and they were not. … Our army will win because it deserves to win through being ready and being complete and being efficient. Don’t discount the efficiency of our navy either. Remember, we Germans have the name of being thorough. When our fleet meets the British fleet I think you will find that we have a few Krupp surprises for them.’”

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

The Great War: October 17, 1914

By this week 100 years ago, the war had stopped moving.

After just two months of fighting, the Western Front was locked in a stalemate. For the next four years, there would be no significant movement across a battle line that extended from neutral Switzerland to the coast of the North Sea.

No one had expected this in 1914. Germany had launched its campaign with a bold assault across Belgium. For weeks they pushed back every Allied army in front of them — the Belgian, the French, and the English. The plan called for the German armies to sweep down into France, surround the remaining Allies, and capture Paris.

It might have worked, but a fresh French assault on the right side of the German line caused a split to form between the German armies. The French and British troops rushed into the gap. The German advance halted, then fell back to the Aisne River.

Both sides realized the way ahead was completely blocked, but there was still a chance to move around the enemy. The Germans began rushing to slip around the left side of the British army, while the British tried to slip around the right flank of the Germans. Both armies began racing north, trying to outflank each other. But they only succeeded in extending the battle line all the way across Belgium to the coast.

For the next four years, the Western Front would change very little. (The Eastern Front, between Russia and the Central Powers, would change quite a bit.) At no point would any army be able to shift the front lines more than a few miles, though both sacrificed thousands of men to break the enemy’s line.

Sherman Said It; Looking for War in a Taxicab — and Finding It

By Irvin S. Cobb

Irvin Cobb grabbed a taxicab in Brussels and said, in essence, “Follow that war.” When the driver would go no father, Cobb and his companions continued on foot into a small Belgian town.

“A minute later … we had gone perhaps 50 feet beyond the mouth of this alley when two men, one on horseback and one on a bicycle, rode slowly and sedately out of another alley, parallel to the first one, and swung about with their backs to us. I imagine we had watched the newcomers for probably 50 seconds before it dawned on any of us that they wore gray helmets and gray coats, and carried arms — and were Germans! Precisely at that moment they both turned so that they faced us; and the man on horseback lifted a carbine from a holster and half swung it in our direction.

“Realization came to us that here we were, pocketed. There were armed Belgians in an alley behind us and armed Germans in the street before us; and we were nicely in between. If shooting started the enemies might miss each other, but they could not very well miss us. Two of our party found a courtyard and ran through it. The third wedged himself in a recess in a wall behind a town pump; and I made for the half-open door of a shop.

“Just as I reached it a woman on the inside slammed it in my face and locked it.

“Then a troop of uhlans [cavalry] came, with nodding lances, following close behind the guns; and at sight of them a few men and women, clustered at the door of a little wine shop calling itself the Belgian Lion, began to hiss and mutter, for among these people, as we knew already, the uhlans had a hard name.

“At that a noncommissioned officer — a big, broad man with a neck like a bullock and a red, broad, menacing face — turned in his saddle and dropped the muzzle of his black automatic revolver on them. They sucked their hisses back down their frightened gullets so swiftly that the exertion well-nigh choked them, and shrank flat against the wall; and, for all the sound that came from them until he had holstered his gun and trotted on, they might have been dead men and women.”

Liberty—a Statement of the British Case

By Arnold Bennett

Most First World War historians avoid placing responsibility for the conflict with any one government. In fact, historians are now so careful not to ascribe guilt to any country, it seems the war was nobody’s idea. It just happened, apparently.

During the war, though, there was none of this hesitation. Everybody knew who started the war — “the other side.” Here, Englishman Arnold Bennett, author of 30 novels, states in no uncertain terms that Germany and Austria were to blame. What the Post didn’t know when it printed Bennett’s article, was that he was working for the British War Propaganda Bureau.

“The German military caste is thorough. On the one hand it organizes its transcendently efficient transport, if sends its armies into the field with both gravediggers and postmen, it breaks treaties, it spreads lies through the press, it lays floating mines, it levies indemnities, it forces foreign time to correspond to its own, and foreign news-papers to appear in the German language; and on the other hand it fires from the shelter of the white flag and the Red Cross flag, it kills wounded, even its own, and shoots its own drowning sailors in the water, it hides behind women and children, it tortures its captives, and when it gets really excited it destroys irreplaceable beauty. …

“If Germany triumphs, her ideal — the word is seldom off her lips — will envelop the earth, and every race will have to kneel and whimper to her: ‘Please may I exist?’ And slavery will be reborn; for under the German ideal every male citizen is a private soldier, and every private soldier is an abject slave — and the caste already owns 5 million of them. We have a silly, sentimental objection to being enslaved. We reckon liberty — the right of every individual to call his soul his own — as the most glorious end. It is for liberty we are fighting. We have lived in alarm, and liberty has been jeopardized too long.”

Hoping to make an ally out of the United States, Bennett was careful to mention a book that had recently surfaced, written by a member of the German army’s staff. In “Operations Upon the Sea”, Franz Frieherr von Edelsheim proposed an eventual assault on America.

“Von Edelsheim … begins by stating that Germany cannot meekly submit to ‘the attacks of the United States’ forever, and that she must ask herself how she can ‘impose her will.’ He proves that a combined action of army and navy will be required for this purpose, and that about four weeks after the commencement of hostilities German transports could begin to land large bodies of troops at different points simultaneously. Then, “by interrupting their communications, by destroying all buildings serving the state, commerce and defense, by taking away all material for war and transport, and lastly by levying heavy contributions, we should be able to inflict damage on the United States.” Thus in New York the new City Hall, the Metropolitan Museum and the Pennsylvania railway station, not to mention the Metropolitan Tower, would go the way of Louvain [a Belgian town where Germans burned, looted, and shot civilians], while New York business men would gather in Wall Street humbly to hand over the dollars amid the delightful strains of ‘The Watch on the Rhine.’ [A rousing German song from the 1850s, which asserted that the Rhine river must always remain German. It became an unofficial theme song for militant German nationalists during both world wars.]”

New Factors in War

By Samuel G. Blythe

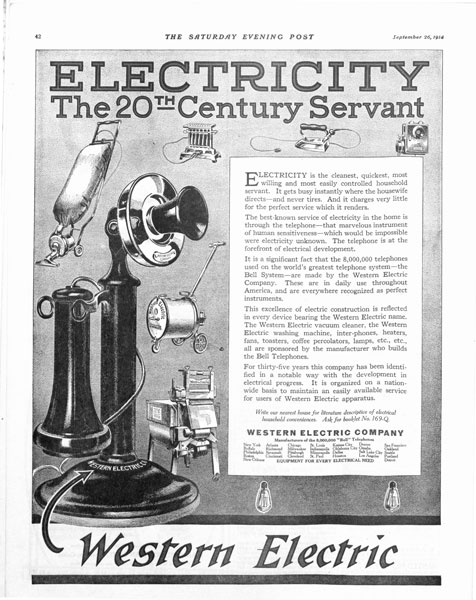

In this report, Blythe observed several developing trends in the ancient art of war. Not only was the horse being replaced but soon airships would be bombing Paris and London. Even more ominous were the reports that France had developed a lethal gas for use on the battlefield. (The first poison gas attack on the Western Front was launched by the Germans in January 1915).

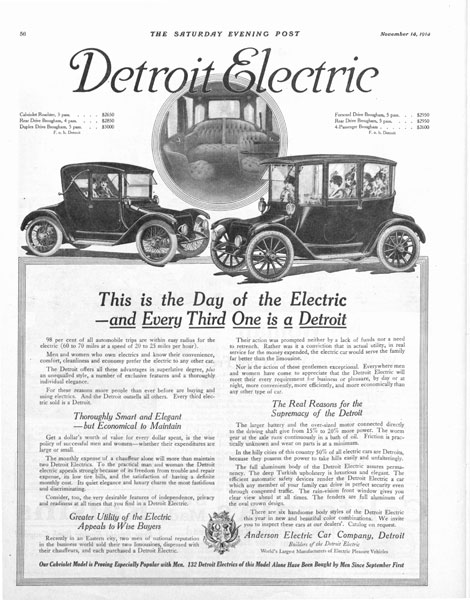

“It has been an axiom of war since wars began that an army travels on its belly. This war, which is the greatest of all wars, has made it necessary to revise that statement. As it now is, an army travels on its gasoline.

“Food, next to men, is the oldest factor in war, and gasoline is one of the newest. Of the two, gasoline—or petrol, as they call it over here — is the more important, because, as modern armies are organized and used, as well as from the sheer size of them, there would be little food for the soldiers if there were no gasoline.

“No staff officer goes anywhere on a horse. He uses an automobile. More than that, the Germans, and presumably the French, have taken auto delivery trucks of the heavier type and mounted field guns on them. These can be moved in any direction almost instantly. They constitute the most mobile artillery the world has ever known. In other wars artillery was shifted by horse or by hand. In this war some of the lighter guns are automobile guns, and they can be transferred from one point to another while horses are being brought up.

“I was told that a Frenchman had invented [a] identical gas that the imaginations of various novelists have invented for use in war fiction — a gas that is so frightful in its effect that when it is liberated all human beings and all living things within a large radius are instantly asphyxiated.

“I was told further that the French Government had the secret of the composition of this gas; that it had been proved out on sheep and cattle — that, at about the time I heard of it, a shell containing it was dropped two hundred feet from a flock of sheep, and that the sheep died instantly when the gas reached them.”

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

The Great War: October 10, 1914

From pages of the Post, October 10,1914: A forgotten American humorist turns war reporter, the war finds an unofficial theme song, and a doctor’s optimistic prediction of death is proved false.

A Little Town Called Montignies St. Christophe

By Irvin S. Cobb

You probably wouldn’t know the name Irvin S. Cobb unless, like me, you haunt the dustier shelves in used bookstores. Far in the back, usually in the humor section, I’ll find at least one of his books; he published over 60 titles between the 1900s and the 1940s.

Back in those years, Americans apparently couldn’t get enough of him. He was America’s highest paid short story writer. He also wrote movie scripts, appeared in motion pictures and on radio, traveled the lecture circuit, and hosted the 1935 Academy Awards. And he produced a mountain of work for the Post: [180 articles and stories between 1909 and 1922].

In 1914, Cobb decided to join the long line of American humorists who went to Europe to write a travel book. His series, titled “An American Vandal,” ran in the Post from March through June that year. No sooner had he returned to the States than the war started in Europe. Although he’d made his reputation as a humorist and storyteller, Cobb was still a journalist at heart. He jumped at the chance to report a war. He set off for the frontlines and, just across the French border, came across “A Little Town Called Montignies St. Christophe.”

It was a sleepy Belgian village when Cobb passed through it in the spring, but now he was giving the village a second, serious look.

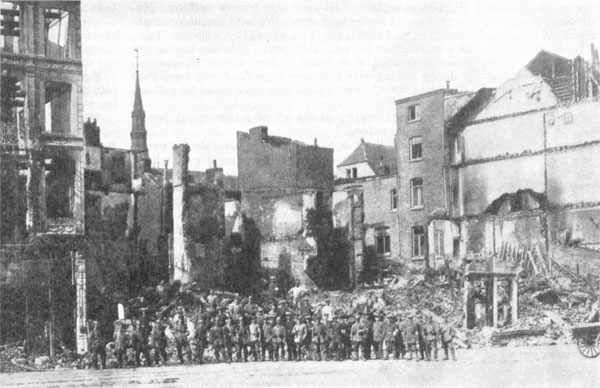

“Something has happened to Montignies St. Christophe to lift it out of the dun, dull sameness that made it as one with so many other unimportant villages in this upper left-hand corner of the map of Europe. The war has come this way; and, coming so, has dealt it a side-slap.

“A six-armed signboard at a crossroads told us its name — a rather impressive name ordinarily for a place of perhaps twenty houses, all told. But now tragedy had given it distinction; had painted that straggling frontier hamlet over with such colors that the picture of it is going to live in my memory as long as I do live.

“Every house in sight had been hit again, and again, and again. One house would have its whole front blown in, so that we could look right back to the rear walls and see the pans on the kitchen shelves. Another house would lack a roof to it, and the tidy tiles that had made the roof were now red and yellow rubbish, piled like broken shards outside a potter’s door. The doors stood open, and the windows, with the windowpanes all gone and in some instances the sashes as well, leered emptily at us like eye-sockets without eyes.

“Until now we had seen, in all the silent, ruined village, no human being. The place fairly ached with emptiness. Cats sat on the doorsteps or in the windows, and presently from a barn we heard imprisoned beasts lowing dismally; but there were no dogs. We had already remarked this fact — that in every desolated village cats were thick enough; but invariably the sharp-nosed, wolfish-looking Belgian dogs had disappeared along with their masters. And it was so in Montignies St. Christophe.

“On a roadside barricade of stones, chinked with sods of turf … I counted three cats, seated side by side. It was just after we had gone by the barricade that, in a shed behind the riddled shell of a house, which was almost the last house of the town, one of our party saw an old, a very old woman, who peered out at us through a break in the wall. He called out to her in French, but she never answered — only continued to watch him from behind her shelter. He started toward her and she disappeared noiselessly, without having spoken a word. She was the only living person we saw in that town.”

Sidelights on the War

By Samuel G. Blythe

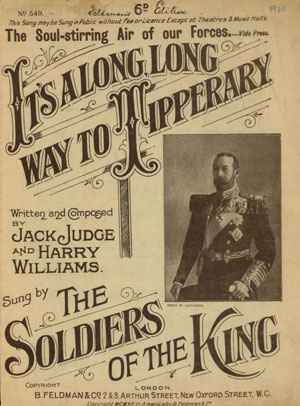

Just two months old and the war already had an unofficial theme song. Its brisk march tempo captured the spirit of the time so well that even today, when so much has been forgotten about the war, many will still recognize it as one of the signature songs of the conflict.

“The marching song and the fighting song of the British soldiers and the British sailors is not ‘God Save the King!’ or ‘Rule Britannia!’ or any other classic. The marching song and the fighting song of the British soldiers and the British sailors is: ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary!’ And that song is an inconsequential music-hall ditty, just as was ‘A Hot Time in the Old Town!’ And this is how the chorus goes:

It’s a long way to Tipperary,

It’s a long way to go;

It’s a long way to Tipperary—

To the sweetest girl I know !

Good-by, Piccadilly !

Farewell, Leicester Square !

It’s a long, long way to Tipperary;

But my heart’s right there!

“This is the song that the British soldiers and sailors sang when they went to France and to sea, which they sang in the fighting all along the line, and which they are still singing, and will sing to the end of the war. … It roars and rolls over the barracks and the camps; and even the French have re-constructed it as ‘Le Chemin a Teeperaire,’ and are singing it too.”

Listen to “It’s a Long Way To Tipperary” by the great Irish tenor John McCormack.

Read the entire article “Sidelights on the War” by Samuel G. Blythe from the pages of the Post

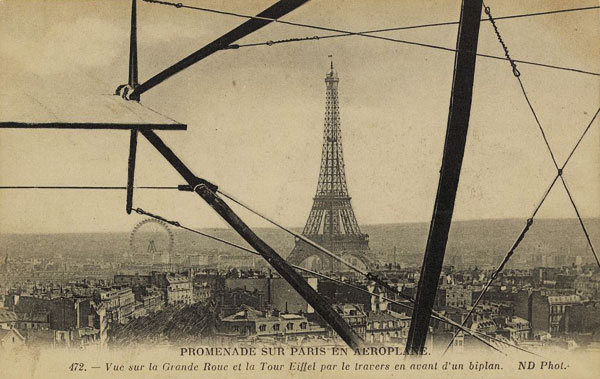

The Hour of Aëroplanes

By F.S. Bigelow

Ah, the French esprit. Here is an amusing example of the bright, happy spirit of the French in the early days of the war, before thousands of deaths darkened the country’s mood.

“In a single week this became a veritable institution. At half past four, or perhaps at five, the planes began to appear. Suddenly the streets swarmed with people who wanted to see them. The Place de l’Opéra may fairly be said to be the center of Parisian sidewalk life. Every afternoon this square was closely packed with eager sightseers. When a plane was sighted the crowd in the square set up a shout and the people at the café tables rushed into the street to get a better view. Much of the talk was of bombs, planes, and Zeppelins.

“By no means were all the aircraft that passed over the city hostile. Indeed, most of them were French scouts; still, it took two looks to distinguish friend from foe. … The simplest rule is that friends fly low and foes remain aloft out of danger.

“There is no doubt the first bomb-dropping foray made the city nervous; but Paris made a fête of it, nevertheless. Army officers sitting at sidewalk café tables rushed into the streets and discharged their revolvers at the aerial enemy, quite regard-less of the fact that he was far out of range. Still, the shooting was fun and it added to the excitement. The higher military authorities, not to be outdone, mounted ma-chine guns on the public buildings and took futile pot shots at the gun-shy strangers.

“Before a week had passed the Hour of Aëroplanes had become such an institution that old men, bearing hand bags full of opera glasses, were wending their way among the sidewalk tables, renting their glasses to those who wished a better view.

“When a plane was sighted it was almost a point of café etiquette to warn your companion to raise her lilac parasol to keep off the bombs. If your careless neighbor, rising hastily, overturned your little table and sent a carafe of water or a siphon of soda crashing to the sidewalk, the delighted crowd exclaimed, ‘A bomb ! A bomb!’ and showed every sign of glee while the waiter was sweeping up the broken glass.”

The Wreck of a Continent

By Samuel G. Blythe

Europe’s collision with war reminded Blythe of the days that followed the Titanic’s collision with an iceberg. Now, as England began shaking off its shock and disbelief, it was handing unprecedented powers over to its wartime government.

“I sat in the visitors’ gallery of the House of Commons a few afternoons ago and heard the legislators there passing law after law of the most sumptuary character, without sword of debate, without question, without a protest of any kind. Measure after measure came up and was hurried through on that afternoon, and on other afternoons, placing the control of the people of England — the absolute control — in the hands of the Privy Council and the military and the naval authorities, which are the state; for by the passing of these acts the Parliament voted itself subordinate to the men who are thus empowered to act. Parliament abrogated many of its own functions, recognized the emergency, and placed itself in un-questioning obedience to the supreme power.”

The Unemotional Frenchman: A Wartime Trip Through the Southern Provinces

By Homer Saint-Gaudens

Homer Saint-Gaudens, son of the famous American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, found himself stranded in a French town also named Saint Gaudens when the war broke out. His two-part article showed the French quietly resigning themselves to war.

“Here had been a perfect opportunity for flags, confusion, illogical demands on the government, irresponsible moves by the government, extras, scareheads, and patriotic drunkenness. Yet none of these appeared. When the call came each man heaved a sigh of regret, laid down his tools and stood ready. The government was of his choosing. It had prepared the country for the crisis before it. He had infinite faith that all measures had been taken for the national safety. What these were he did not know. Were he to know everybody would know, the country’s enemies would know. His task was to obey the call to arms. He did not complain or criticize.

“The roads we found deserted of teams, the fields deserted of laborers. In the doorways stood women. Toward the railroad station moved a young man and a girl. The man had a bundle in one hand, the other was on the girl’s shoulder. From the station came three girls walking quickly up the road, hand in hand, crying. Only women came from the stations. One and all were dressed in black—most of them had been weeping. More and more we became the unwilling witnesses of other persons’ domestic tragedies.

“We had seen recruits before, mostly huddled together like cattle driven to the slaughter. We had heard the Marseillaise sung before, especially in that maudlin fashion in Saint-Gaudens. These men were neither cattle nor maudlin. They were unkempt and they perspired. They were dirty. They smelled of garlic and their bundles were awry. But they were sober, and they were proud as they passed up the hot, sunlit street; and they sang the song of their land and marched it as their fathers must have marched and sung it when first it was written.”

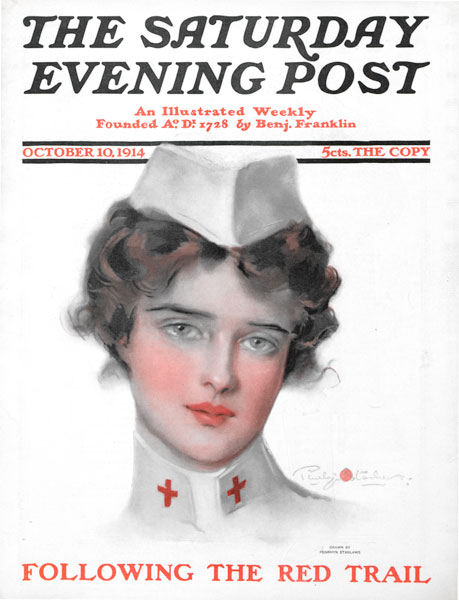

Following the Red Trail: The Real Perils of War

By Woods Hutchinson

A professor of clinical medicine and a medical writer, Hutchinson was optimistic that modern medicine would help control the casualty numbers of the war. Combat deaths declined in every successive war, he noted, and he expected they would remain low in the coming months.

“The cheerful pastime of slaughtering our fellow men has, in the most recent wars, been carried on with smaller loss of life and less suffering and hardship, both to the actual combatants and to the noncombatants in whose territories the war is waged.

“The average death rate of the first three great wars of the past century — the Napoleonic, the Mexican, and Crimean — was 12.5 percent a year; that of the last three wars — the Spanish-American, the Boer, and Russo-Japanese — was 4.8 percent.

“By the time the Napoleonic wars were reached, the mortality from deaths in war, from all causes, had fallen to about 125,000 a year, or about 12 percent.

“In our own Civil War, it fell to 10 percent.

“The Sedan campaign cost the German army only 8 percent of its three-quarters of a million men; while our Spanish-American and England’s Boer War reached the low-water mark, with barely 3 and 4 percent of loss respectively.

“As to the cause of this gratifying reduction in war fatalities, several influences have been at work. One of the most obvious has been that the invention of gunpowder and the improvements of rifles and artillery, with such enormous increase in their range of death dealing, has steadily forced more and more of the fighting to be carried on at long range.

“The net result of this has been that not nearly so many men are actually hit as in the days of old point-blank firing by platoons; that as a battle becomes a long-range duel … its fate is decided more and more by maneuvers such as surrounding a force or cutting it off from its base than by actual sacrifice of life, or by weight of numbers in a bayonet charge.

“The other most important change … was that in the old days, when battles were decided by hand-to-hand fighting, the victors were literally right on top of the vanquished the moment the tide turned and the retreat began; and only superior fleetness of foot or length of wind could save a very large percentage of the beaten troops from slaughter, maiming, or slavery.”

Despite Hutchinson’s predictions, the First World War quickly surpassed single-digit casualty rates. The percentage of casualties in Great Britain’s forces was 36 percent. It was 65 percent for Germany, 76 percent for Russia, and 90 percent for Austria-Hungary. (The casualty rate for American forces, which were engaged for only 17 months, was 7percent.)

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

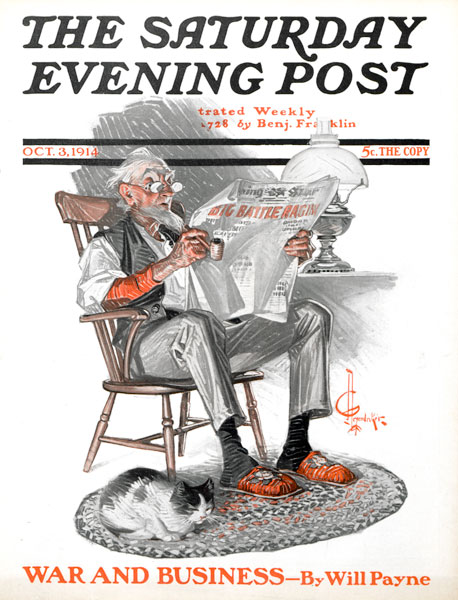

The Great War: October 3, 1914

From the Post October 3, 1914: A Post author gets swept up with Belgian refugees fleeing the advancing German army, Americans become desperate to get home, and tragedy jars the British awake.

The Refugees: A Night Among the Peasant Fugitives at Ostend

By Reginald Wright Kauffman

By October, many Americans caught in Europe when the war began had finally secured passage home. Among the eyewitness contributors in this week’s issue was the American author Reginald Wright Kauffman who painted a vivid picture of a Belgian resort town crowded with war refugees.

“When I left it, Ostend looked like the lakefront of Chicago must have looked during the great fire.

“Picture to yourself Atlantic City [with] three times its accustomed population … crowd them along all the pavements of all the streets, up the Boardwalk and down; toss them on to the beach — women, children and old men, some wounded, more ill, all robbed of their material possessions, and many robbed of the lives of those they loved best on earth!

“Do this, and you have Ostend as I saw it.

“I was in the midst of the refugees; and from that moment, wherever I went about the town, I remained surrounded by them. … I saw one young woman in a bedraggled wedding dress and was told that, her fiancé having been called to the front on the day before that set for their wedding, she had gone mad and insisted on wearing her wedding dress when she fled with her mother from the oncoming Germans.

I saw two graybeards with great crêpe rosettes on their hats, and they explained to me that they were mourners at a funeral in their village when the [cavalry] suddenly appeared; the coffin was hastily lowered into the grave and the entire funeral party took to their heels.

“I talked with a tottering woman of 25 whose husband had been called to the colors and killed in the first day’s fighting about Liege. She had with her a son of 5, who was staggering under the weight of his 18-month-old sister; another sister carried a basket as large as herself, and the mother had in her arms an infant that she vowed had been born to her on the roadside only 36 hours before.

“‘What will you do?’ I helplessly asked her.

“She made the sign of the cross.

“‘What the good God wishes,’ she answered.

A few yards behind her a girl, who might have been 18 years old, was lying where she had fallen a minute before. She was beautiful, with black hair and a creamy skin; and her face was very calm. A wound, some one explained, had reopened — a wound inflicted by a stray shot some days since. I bent over to speak to her; she was dead!

England Wakes Up

By Samuel G. Blythe

Meanwhile, Samuel G. Blythe, still in England, reported on how the news of the first major engagement of the war struck the British.

“At three o’clock on the afternoon of August twenty-fifth—three weeks after England’s actual declaration of war—the newsmen came up the street with red [placards], and the Londoners looked at them and saw, yelling at them in the biggest possible type:

‘Two Thousand British Casualties—Official!’

The men had fallen at the Battle of Mons, in Belgium, where the British army had vainly tried to stop the German advance toward France. The official casualty figure has been calculated as 1,600, which is still a staggering figure of dead and wounded. Much, much higher figures were to come in the months ahead.

On the day before there had been a dispatch saying that a few English soldiers, including an earl, had been wounded; but that was nothing. Of course, as the Londoners and the provincials viewed it, a few men, more or less, must be hurt in an enterprise of this kind. That was to be expected.

The news that two thousand British soldiers had been wounded, perhaps killed—casualties is an all-embracing word—fell on London like a bomb dropped from the sky. It shocked, surprised and stunned…

“They began to wake up. Two thousand British casualties! Why, it was only a day or two before that they had known that the British troops had been sent to the Continent.”

Taking the Cure: The Treatment of Americans for Europitis

By Corinne Lowe

Writer Corinne Lowe seemed to relish the sight of panicked Americans desperate to get a ship’s berth out of war-torn Europe. Her scorn for Americans seeking culture in the Old World was shared by the Post editors. In the coming months, they ran several articles and editorials that mocked Americans who had snubbed their homeland to pursue Europe’s quaint, continental charms.

Writer Corinne Lowe seemed to relish the sight of panicked Americans desperate to get a ship’s berth out of war-torn Europe. Her scorn for Americans seeking culture in the Old World was shared by the Post editors. In the coming months, they ran several articles and editorials that mocked Americans who had snubbed their homeland to pursue Europe’s quaint, continental charms.

“Picturesqueness! There is the Pied Piper who has led us children of the Western Hemisphere out of our cool verandas and comfortable homes, who has made us turn from the Grand Canyon in order to sit at a smelly café where we could see a Franciscan monk or a booted and spurred officer. …

“Undoubtedly the principal factor in this life of Europe was constituted by the officers. What strange compensating joy there has been, for the most of us, in the sight of a handsome Austrian colonel crunching his morning roll at an outdoor café ! One glance at those fawn-colored ‘panties,’ at that tidy little green coat, and those fierce mustaches, and I have seen a little New Jersey school-teacher crumple up in a rapturous colic. ‘Isn’t it too lovely!’ I have heard her babble. ‘That’s what we do miss in America — the color of it all.’

“In our bondage to this foreign ‘atmosphere’ we have gradually lapsed into the belief that the militarism of Europe has been carried on for the special refreshment of the American public.”

War and Business

By Will Payne

While the Post reported on the political and social aspects of Europe’s war, it never lost of sight of the impact it would have on American business. Will Payne explained why the outbreak of fighting 3,000 miles away had caused America to close trading on July 31, 1914 it wouldn’t reopen until November 28.

“In the United States the first violent effect of the war was the closing of the New York Stock Exchange. It is clear now that this step was inevitable; yet so little were people prepared for war — so little were the effects of war on modern business conditions really understood in advance — that 10 minutes before the Exchange closed many persons of ordinarily good judgment believed it would remain open.

“The most conservative estimate puts the amount of American securities held in Europe at four billion dollars. If the Stock Exchange remained open we should have to face the possibility of buying immediately, say, a billion dollars of foreign-held securities and paying for them, not in credits, but in gold. We could not possibly do it, [and frankly acknowledged the fact by closing the Exchange]. With no market to sell in, foreigners would have to hold our paper whether they wanted to or not.

“You may have heard somebody mention that this is the richest country in the world. So it is; yet its total fund that is practicably available for the purchase of foreign-held securities under conditions of July 31 is really very small.”

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

The Great War: September 26, 1914

On September 26, 1914, the Post published an introduction to aerial combat and the new fighting “aeroplanes” of the war and a look inside wartime in Paris.

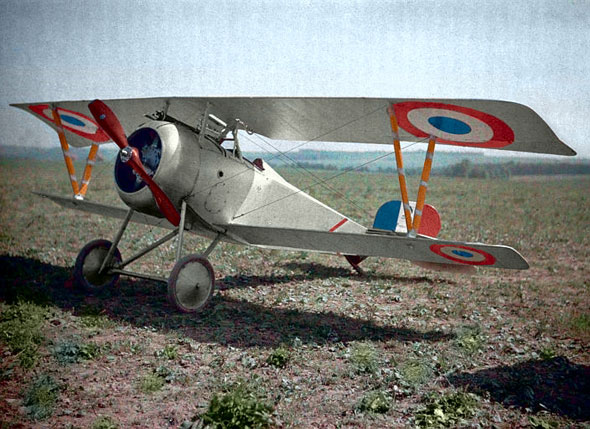

The Air Fleets

By Glenn Curtiss

The Post’s very first article on air combat was written by aviation pioneer Glenn H. Curtiss. Not only was he familiar with the various styles of planes being used by combatants, he could also anticipate the terrors that pilots would face in dogfights long before any had taken place.

“The awfulness of this combat can be imagined by those only who, through personal experience in the upper air, have come to realize the insignificance of objects or individuals in this practically limitless space. Away up there, in machines speeding at the rate of nearly two miles a minute, men need in the clearest weather be but three or four minutes apart to be hopelessly lost from sight of one another; in hazy or cloudy weather an enemy may be within easy striking distance before he is either seen or heard.”

“England is at present the acknowledged leader in the development of [reconnaissance planes] The business of these machines is just what the name suggests. Fast enough in horizontal speed to escape any antagonist seen in reasonable time, they will sail leisurely over the enemy’s lines, while the observers … make accurate records of the disposition of the enemy’s forces. The observer is armed with a quick-firing rifle … though as most of them are tractors, the observer cannot fire at machines directly in front of him, but would have to shoot from above, below or nearly broadside.”

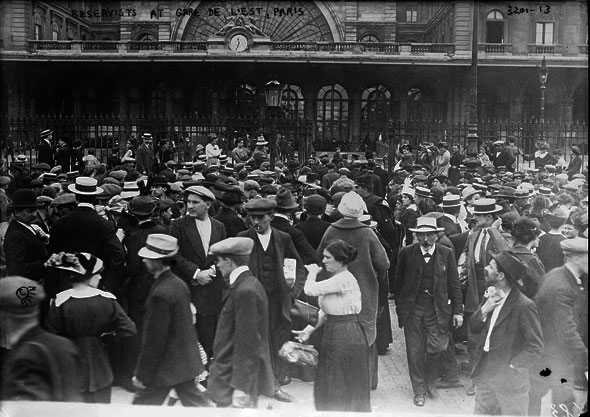

Paris When the War Broke

By Samuel G. Blythe

A week after publishing his account of wartime London, the Post printed Blythe’s report on Paris. He was surprised to see the demonstrative French respond to the war crisis with calm, almost grim determination.

“With the soldiers marched their wives or their sweethearts, or ahead of them, or behind them, cheering their husbands or their lovers on to war. One woman, going to the railway station with her husband, threw their baby into the soldier’s arms just as the train left. ‘Leave him with the station master at the first stop,’ she cried. ‘You may never see him again, and I’ll go and get him.’

“… It is at night that the greatest change is noticed in Paris. The city is silent and deserted after 9 o’clock. The streetlights are maintained, but the streets seem darker than usual, because electric lights are forbidden in shops and cafés after 9 o’clock. All residents of Paris are supposed to be in their homes at that time. The street cafés, that customarily are open always, are closed at 9. In the first days the tables outside the café were forbidden, but now the Parisians are allowed to sit at the little marble-topped tables during the day and sip their grenadine and discuss the war. Most of the harsh-voiced news-venders have gone to war, and the papers are cried by boys, by old men with squeaky voices or by women.”

“All night long the great searchlights play over the dark and silent city, illuminating every alley and every open spot and sweeping the sky in search of German dirigibles and German airships. The territory round Paris is bathed in light constantly for fear there may be some approach. The spy danger is ever present, and the reservoirs and railroad stations and crossings and bridges are closely guarded. The fortifications are filled with men. The trenches are manned. The city calmly waits the event.”

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.

1914: London Goes To War

(Courtesy of The Library of Congress)

This series begins with a surprising eyewitness account of London by Samuel G. Blythe, published in our September 19, 1914, issue. It’s surprising because Blythe’s article contradicts the traditional account of Great Britain’s entry into the war.

Popular histories and movies would give you the impression that the warring nations sent their soldiers off to war amid scenes of frenzied, jubilant crowds. Documentaries such as PBS’ The Great War and the upcoming exhibit at the National World War I Museum assert that there was a general expectation that the war would be over by Christmas.

Doubtless there were people who were excited and pleased by the thought of war and believed it would end quickly, decisively, and victoriously. But the Londoners Blythe saw were far from exuberant. According to his article “London in War Time,” they “watch their soldiers silently — almost stolidly. Whatever emotions they may have are held in check. … The crowds have stood silently alongside the curbs, saying nothing — not cheering — not shouting — just watching.”

(Courtesy of The Library of Congress)

Furthermore, contrary to the myth that the British expected a quick, easy victory, “the great papers are issuing daily and solemn warnings that the war is likely to be long and bloody.”

Most surprising to me is Blythe’s realization, from the war’s first week, that the coming conflict would have a vast impact. “It will change the map of Europe. It will leave its impress on the destinies of the entire civilized world for years and years to come. No person at a distance can comprehend what it all means. No person can comprehend that even here, at one of the centers of activities, or in Paris or Berlin. The impressions bulk too hugely. The mind does not grasp it all. No mind can.

“A world is being overturned. There is to be slaughter unparalleled in history. There is to be sorrow and woe and distress and ruin. There is to be mourning and weeping. There is to be the glory of arms and the grave of ambition and lust for power. Kings may lose their thrones. Republics may arise where monarchies now prevail.”

Many historians argue that the governments and people of Europe had no idea the war would overturn their world. Well, at least one reporter saw fairly clearly where it was heading, right from the start.

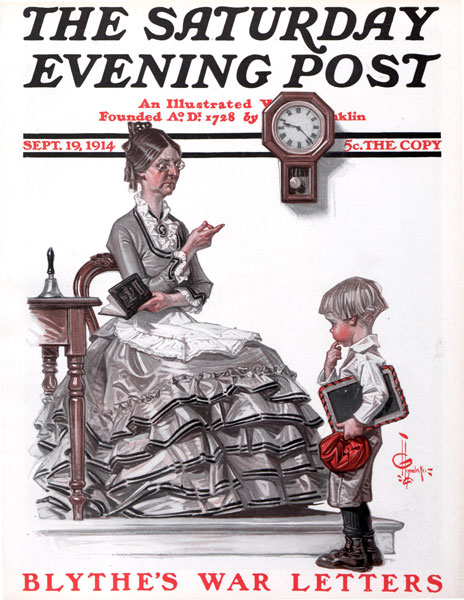

The Saturday Evening Post

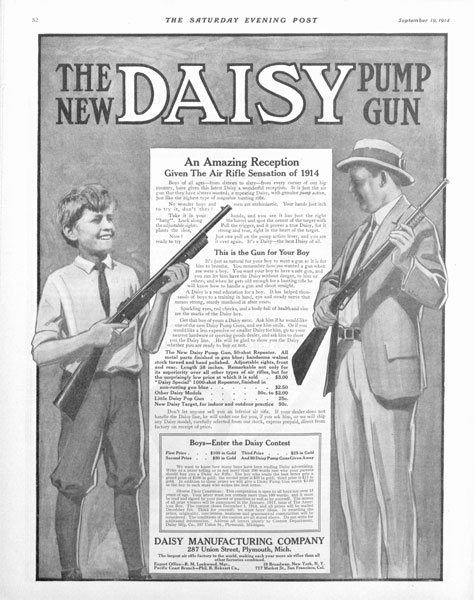

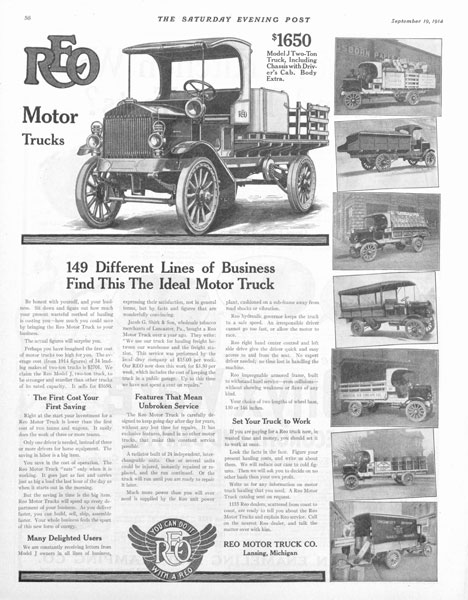

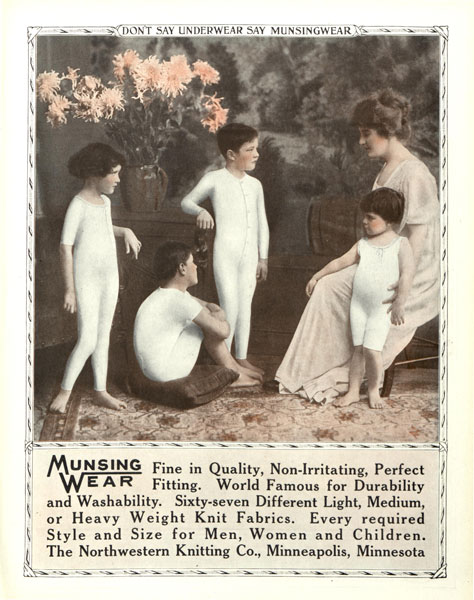

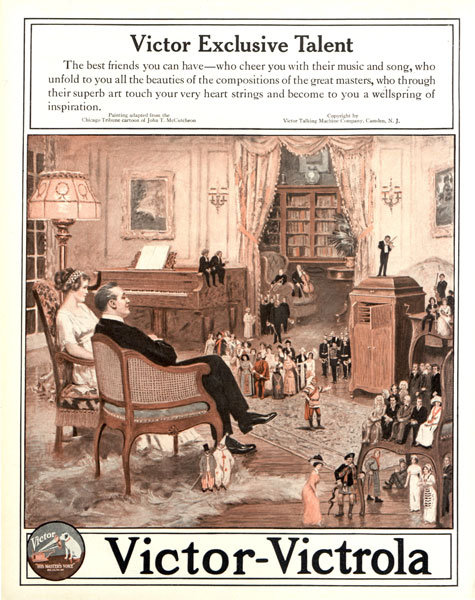

September 19, 1914

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago: