Civil War Hospital Sketches from Louisa May Alcott

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

American novelist Louisa May Alcott wrote about her experiences as a Sanitary Commission nurse in a series of letters for the abolitionist Boston Commonwealth. The letters, published as Hosptial Sketches in 1863, earned Alcott her first public attention as an author and praise for her sensitivity and wit.

The Post published excerpts from Hospital Sketches, a few weeks after Gettysburg, when Union hospitals were overflowing with casualties from the battle. On these pages, Alcott describes caring for soldiers from Fredericksburg in December 1862.

* * *

They’ve come! they’ve come! Hurry up, ladies — you’re wanted.”

“Who have come? The Rebels?”

This sudden summons in the gray dawn was some- what startling to a three days’ nurse like myself, and, as the thundering knock came at our door, I sprang up in my bed, prepared “To gird my woman’s form, And on the ramparts die,” if necessary; but my room- mate took it more coolly, and, as she began a rapid toilet, answered my bewildered question, — (“Bless you, no child; it’s the wounded from Fredericksburg; forty ambulances are at the door, and we shall have our hands full in 15 minutes.”)

The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty.

I chanced to light on a withered old Irishman, wounded in the head. He was so overpowered by the honor of having a lady wash him, as he expressed it, that he did nothing but roll up his eyes, and bless me, in an irresistible style which was too much for my sense of the ludicrous; so we laughed together, and when I knelt down to take off his shoes, he wouldn’t hear of my touching “them dirty crayters”.

Some of them took the performance like sleepy children, leaning their tired heads against me as I worked, others looked grimly scandalized, and several of the roughest col- ored like bashful girls. One wore a soiled little bag about his neck, and, as I moved it, to bathe his wounded breast, I said,

“Your talisman didn’t save you, did it?”

“Well, I reckon it did, ma’am, for that shot would a gone a couple a inches deeper but for my old mammy’s camphor bag,” answered the cheerful philosopher.

Another, with a gun-shot wound through the cheek, asked for a looking-glass. When I brought one, regarded his swollen face with a dolorous expression, as he muttered —

“I vow to gosh, that’s too bad! I warn’t a bad looking chap before, and now I’m done for; won’t there be a thunderin’ scar? and what on earth will Josephine Skinner say?”

He looked up at me with his one eye so appealingly, that I assured him that if Josephine was a girl of sense, she would admire the honorable scar.

The next scrubbee was a nice-looking lad, with a a bud- ding trace of gingerbread over the lip, which he called his beard, and defended stoutly, when the barber jocosely sug- gested its immolation. He lay on a bed, with one leg gone, and the right arm so shattered that it must evidently fol- low: yet the little Sergeant was as merry as if his afflictions were not worth lamenting over; and when a drop or two of salt water mingled with my suds at the sight of this strong young body, so marred and maimed, the boy looked up, with a brave smile, though there was a little quiver of the lips, as he said,

“Now don’t you fret yourself about me, miss; I’m first rate here, for it’s nuts to lie still on this bed, after knocking about in those confounded ambulances that shake what there is left of a fellow to jelly. I never was in one of these places before, and think this cleaning up a jolly thing for us, though I’m afraid it isn’t for you ladies.”

“Is this your first battle, Sergeant?”

“No, miss; I’ve been in six scrimmages, and never got a scratch till this last one; but it’s done the business pretty thoroughly for me, I should say. Lord! What a scramble there’ll be for arms and legs, when we old boys come out of our graves, on the Judgment Day: wonder if we shall get our own again? If we do, my leg will have to tramp from Fredericksburg, my arm from here, I suppose, and meet my body, wherever it may be.”

The fancy seemed to tickle him mightily.

Donation notes to Soldiers

Alcott volunteered with the Sanitary Commission, created in 1861 to help organize donations and volunteers. Throughout the war, the Post published Commission news, including the excerpt below.

— Originally published March 26, 1864 —

Some of the marks on the items sent to the sanitary Commission show the thought and feeling at home:

On a homespun blanket, worn, but washed as clean as snow, was pinned a bit of paper which said: “This blanket was carried by Milly Aldrich (who is ninety-three years old) down hill and up hill, one and a half miles, to be given to some soldier.”

On a bed quilt was pinned a card, saying: “My son is in the army. Whoever is made warm by this quilt, which i have worked on for six days and most all of six nights, let him remember his own mother’s love.”

On another blanket was this: “This blanket was used by a soldier in the war of 1812 — may it keep some soldier warm in this war against Traitors.”

On a pillow was written: “This pillow belonged to my little boy, who died resting on it; it is a precious treasure to me, but i give it for the soldiers.”

On a pair of woolen socks was written: “These stockings were knit by a little girl five years old, and she is going to knit some more, for Mother says it will help some poor soldier.”

On a bundle containing bandages was written: “This is a poor gift, but it is all i had: i have given my husband and my boy, and only wish i had more to give, but i haven’t.”

‘Coming Generations Will Call You Blessed’

This is the last installment of our six-part series on the Civil War, marking the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. To recap: In part one, “The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move,” we described how the Post reported the initial news of the invasion. In part two, “Scrambling for Soldiers,” we looked at the renewed attention to the draft. In part three, “Americans United to Support the Civil War Troops,” we covered the Sanitary Commission, an organization of Union women volunteers whose fight against disease helped save thousands of soldiers’ lives. In part four, “Where the Civil War was Won,” we looked at the Post’s war coverage from the battlefield. And in part five, “Little Women Among the Causalities,” we shared a harrowing description of Louisa May Alcott’s work as a Civil War nurse.

courtesy of the Library of Congress.

One week after the Battle of Gettysburg, the Post’s “Sanitary Commission Department,” a column that reported on the group’s extraordinary work, printed Dr. W. H. Bowman’s moving testimonial to the commission.

The letter is especially impressive because Bowman, a surgeon in the 27th Illinois Infantry, started out with a prejudice common among military doctors against civilian volunteers in their hospitals. But after seeing how much his patients benefitted from the commission’s services, his resentment changed to gratitude.

Bowman saw the Sanitary Commission as a sign of a civilization’s progress and a reflection of a unified spirit that could not be defeated.

Bowman’s idea that mankind had entered a new epoch because of this new effort by volunteers may seem extreme. Yet he had a valid point. Americans were no longer content to let their soldiers struggle and suffer alone on the battlefield. Thousands of volunteers committed themselves to “mitigate the horrors of war” by supporting their fighting men directly. It was the beginning of a 150-year-old tradition, continued by countless organizations today.

Camp Shaeffer, on Stone River

Tenn.

April 30, 1863Dr. A.L. Casleman—

Dear Sir;

Having had some practical acquaintance with the working of the Western Branch of the Sanitary Commission for nearly twenty months, I deem it my duty as a surgeon in the army to express the high appreciation I feel of the efficient and benevolence of your organization.I was, I confess, considerably prejudiced against the operation of the Commission at the start.

In the autumn of 1861, the approach of cold weather, coupled with the fact that my supply of bed clothing was entirely insufficient to keep my sick comfortable, led me to look around anxiously for the means to meet the emergency. Government supplies were not available. At this time your Commission, co-operating with the good ladies of our state, stepped in and supplied the want, which Government, with the immense demand on its energies and resources, had not been able to meet.

Our shivering sick were made comfortable, and I was relieved of a heavy care. I have never ceased to be grateful.

This spring when scurvy appeared in our commands, your Commission furnished us the first and most efficient means for combating it, viz: fresh vegetables. Government is doing its best now but red tape tangles the feet of benevolence.

The many home comforts which, through you, have so promptly reached the sick and wounded in the field, and which could not have been otherwise supplied, have made us feel that patriotic benevolence is a power in the land, and the Sanitary Commission its legitimate mode of expression in the army. You have encountered immense obstacles in your progress, and nobly surmounted them.

Much benevolent, self-denying contributions, doubtless have been wasted in the commencement, owing to want of knowledge of what was most needed and the best way to apply the means. Sometimes it may have been unfaithfully used by unprincipled surgeons. But I think the instances are much more rare than has been imagined.

Our profession has been much slandered in the army. Mean, unprincipled men do sometimes get into our hospitals as patients. When their appetites are held in restraint by the judicious surgeon he is often doubtless maliciously charged with using for himself what he prevents them from unwisely or selfishly consuming.

In the providence of God, good and evil seem to go side by side, that mankind may see and learn the beauty of the one and the hideousness of the other. Your Commission, noble and pure as are its objects and labors, seems to be no exception to this general law.

History will note the advent of your organization as an epoch marking the advance of mankind to a higher civilization and coming generations will call you blessed.

It is the first systematic organized national effort, by voluntary agencies and contributions, to mitigate the horrors of war that the world has ever witnessed. A nation with such an interior life cannot be destroyed. The world cannot do it. God, the Infinitely Just and Loving, will protect such a people.

Go on then in your good work. The time will come when those who have refused to assist, will be ashamed to have it know that they stood aloof. The self-denying contributions to the relief of the brave defenders of the nation’s life will enjoy abundant recompense in the appropriation of the good, and conscious of having acted in harmony with the noblest impulse of humanity

W.H. Bowman

Surg, 27th Ill

and Brigade Surgeon

3rd Div 20th Army Corps

Americans United to Support the Civil War Troops

This is the third installment of our six-part series on the lead up to Gettysburg. To recap: In part one of this series, “The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move,” we described how the Post covered the initial news of the invasion. In part two, “Scrambling for Soldiers,” we looked at the renewed attention to the draft.

Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

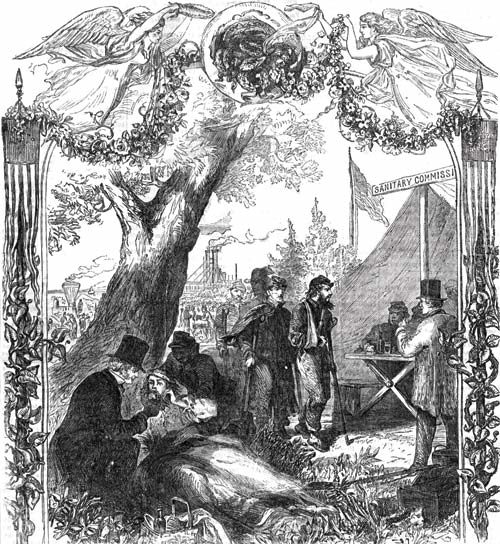

By late June of 1863, three forces were converging on the region around Gettysburg: the Confederate Army, the Union Army, and the United States Sanitary Commission.

The Sanitary Commission was the first large-scale volunteer organization, and it had come a long way in the two years since it was founded in response to widespread disease in Union Army camps. The living conditions in camps were so bad that, over the course of the war, two soldiers died from illness for every one soldier killed in combat.

The commission’s original goal was to keep army bases healthy and clean, and protect their drinking water from contamination. Later, it expanded the scope of its work and broadened its operation to 7,000 local chapters across the Northern states. The commission was based in the North and served the Union Army, but would also help wounded Confederate soldiers that had been captured.

Its army of women volunteers—numbering in the tens of thousands—gathered medical supplies, food, and clothing for the wounded soldiers, and sometimes provided aid to their families. Most important, perhaps, it began providing nursing services after the organization overcame the prejudice of the Army Medical Bureau.

When the commission heard the Confederate Army was marching north, it began gathering information from its agents with the Union Army, who reported the movement of troops and made estimates for the coming battle’s casualties. The Sanitary Commission’s general secretary, Frederick Law Olmsted, told Post readers that its officers used this information to estimate how big the upcoming battle would be and what supplies would be needed. The commission then began distributing supplies to sites in areas close to all the expected targets.

As soon as Olmsted knew the heavy fighting had begun at Gettysburg, he moved operations to a nearby railway junction near the town and obtained railroad cars to run medical supplies up to the front. The commission also sent supplies by wagon, which arrived just as Gen. James Longstreet began his attack on the Union left flank.

The wagons pulled up to the field hospital, just 500 yards from the shooting, where several hundred men were awaiting medical help. According to Olmsted’s account in the August 1 Post, “A surgeon was seen to throw up his arms, exclaiming ‘Thank God! Here comes the Sanitary Commission. Now we shall be able to do something.’ He had exhausted nearly all of his supplies; and the brandy, beef soup, sponges, chloroform, lint, and bandages, that were furnished him were undoubtedly the means of saving many lives.”

Later, wounded soldiers that could still walk made their way to an open field by the railway line and awaited transport to hospitals. They soon discovered the army had no provisions for sheltering them from the rain, or for feeding them as they waited for evacuation. The commission quickly put up tent shelters and set up a kitchen, which fed up to 2,000 wounded men each day.

Throughout 1863, a regular Post column called “Sanitary Commission Department” featured news about the work of the commission. It also included requests for help, like these excerpts from June and July 1863:

We have lately received a letter from Washington, saying that pickles and domestic wines are needed, and that their storehouses have none.

[We have received] the pattern of a ‘Ration Bag,’ with the following remarks as to its usefulness: ‘The idea is to furnish each solider with two bags (one for sugar and one for coffee), to put inside the haversack, so as to keep the two articles from being spoiled, either by being wet from rain or in crossing streams, or by coming in contact with the greasy pork and bacon …’

We have received a requisition for arm-slings, with the following directions for making them: ‘They should be made to fit on the underside of the arm, from the elbow to the hand, and at equal intervals should be furnished with several tapes …’

Occasionally, this department received testimonials, like this letter from a wounded soldier to the “noble ladies” of the Women’s Soldier’s Aid Society of Northern Ohio.

I want to thank you. I was wounded at Stone River on the last day of December 1862, and since then I have run the gauntlet of the hospitals from Murfreesboro to Cleveland. At every stage of my painful progress I was the grateful recipient of your priceless gifts. I owe the preservation of my life to a bottle of blackberry wine, sent to me by Mr. Atwater, Agent of the United States Sanitary Commission at Murfreesboro. It came to me a time when I had scarcely any vitality left. It restored my appetite, which I had lost to the too free use of Morphine. That wine could not have been bought with money; it was the priceless gift of some great-hearted countrywoman—God bless her!

The Sanitary Commission was unique; for the first time, American civilians operated a large-scale, volunteer effort that provided direct help for soldiers. Women living too far from hospitals to nurse the wounded still had a unique opportunity to help the war effort. As one volunteer expressed it, “It is difficult to connect gray flannel and blue yarn with the thought of a great historical movement; yet our work is really in such connection, and each stocking or shirt we make for the soldiers is portion of a story that has never had its counterpart.”

The resources of the Sanitary Commission would be heavily taxed in the coming battle, in which 14,000 Union soldiers were wounded. In the days following the battle, the commission’s agents also provided help to 5,000 rebel casualties who remained behind in 11 Confederate hospitals.

Some of the commission’s hospital workers felt that, even amid the suffering, some of the best traits of humanity—humility, gratitude, compassion—would emerge. As one correspondent wrote, “There is no hospital which could not furnish in volume incidents that would do honor to human nature.”

Coming Next: The Post Reports the Battle of Gettysburg