‘I Saw Lee Surrender’

Seth M. Flint, an 18-year-old bugler with the Union Army, was present at the truce ending the Civil War. In 1940, Flint, the last living witness, wrote his recollections for the Post, highlights of which are excerpted here:

Grant calmly receives a historic letter from Lee:

Grant handed the paper to a staff officer, who hurriedly scanned the words. Evidently the staff officers construed this to be assurance of surrender, for every last man of them burst into cheers. The only one who took no part in the impromptu celebration was General Grant, who merely looked on with bland amusement.

A party of Union soldiers rides to meet Lee:

It was not difficult to recognize the famous commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. It was the face beneath the gray felt hat and hair that made the deepest impression on me; I say this because I can still recall it vividly. … Despite its sternness on that day of long ago, I would still call his expression benign. And yet, I remember well that there was something else about him that aroused my deep pity that so great a warrior should be acknowledging defeat.

Grant arrives at the house of Alexander McLean:

Grant looked an old and battered campaigner as he rode into the yard. His single-breasted blouse of blue flannel was unbuttoned at the throat and underneath it could be seen his shirt. His top boots were spattered with mud, and splotches of mud were on his trousers. Unlike Lee, he wore neither sword nor sash, and the only marks of his rank were his shoulder straps.

The day was very warm for early April. Spring was with us at last, and the trees were putting on a tinge of green, the buds showing plentifully on the branches. It was good to be alive on April 9, 1865, and it would be better still if this was the end of four years’ war. … The Sabbath stillness brooded over the land, a welcome relief from the din and hustle and carnage of recent fighting.

That night when I sounded taps, that sweetest of all bugle calls, the notes had scarcely died away when from the distance — it must have been from General Lee’s headquarters — came, silvery clear, the same call; and, despite the sadness of the hour to the boys on the other side, I have a notion that they, like the Yanks, welcomed the end of hostilities and the coming of peace.

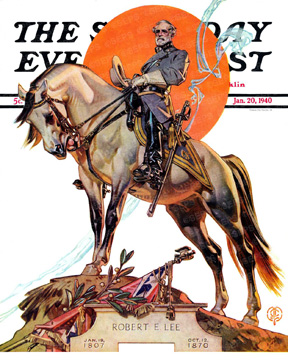

Robert E. Lee on Traveler

J.C. Leyendecker

January 20, 1940

A day later, Union horsemen mingle casually with officers in gray:

I remember how amazed I was as I saw that strange company; and when I learned that among them were Longstreet, Pickett and Gordon — well, it certainly seemed impossible.

Perhaps you can imagine my reaction to the spectacle, after three years of desperate fighting, to see three of the most famous Southern leaders, within 24 hours of Lee’s surrender, shaking hands with Grant and chatting like long-absent neighbors with him and other Federal generals.

How Abe Lincoln would have enjoyed that confab! Like Grant, he would have grasped the hands of those soldiers in Confederate gray and welcomed them back home. Had he been spared, there would have been no Reconstruction.

Soldiers don’t carry hatred; they leave that to the stay-at-homes. We learned that in the next 20 years.