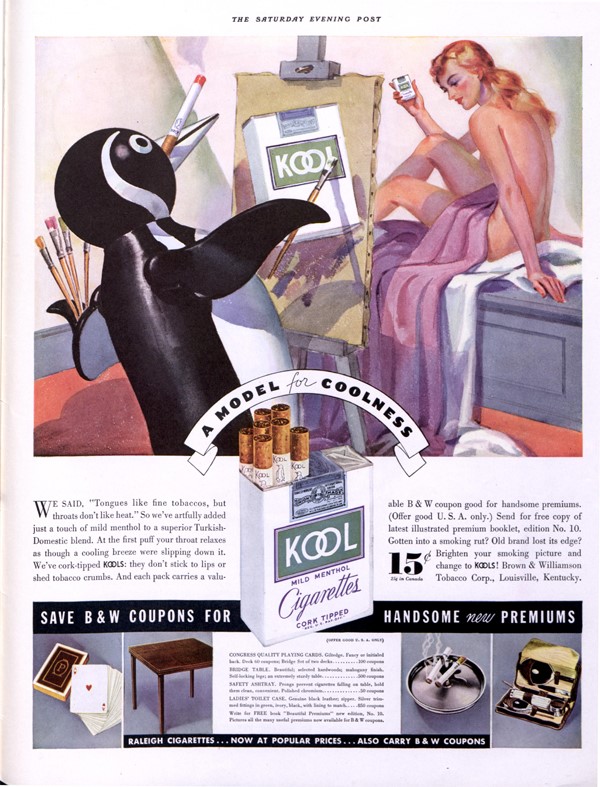

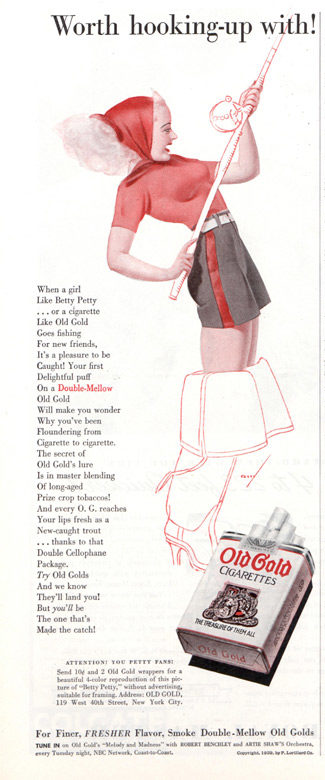

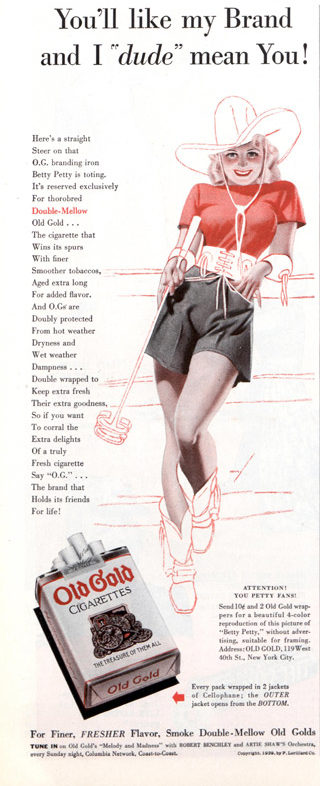

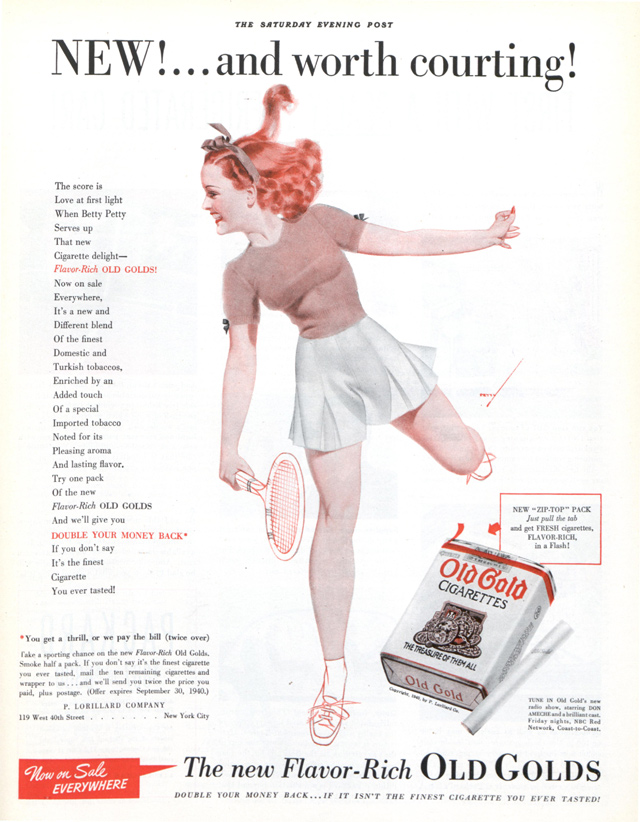

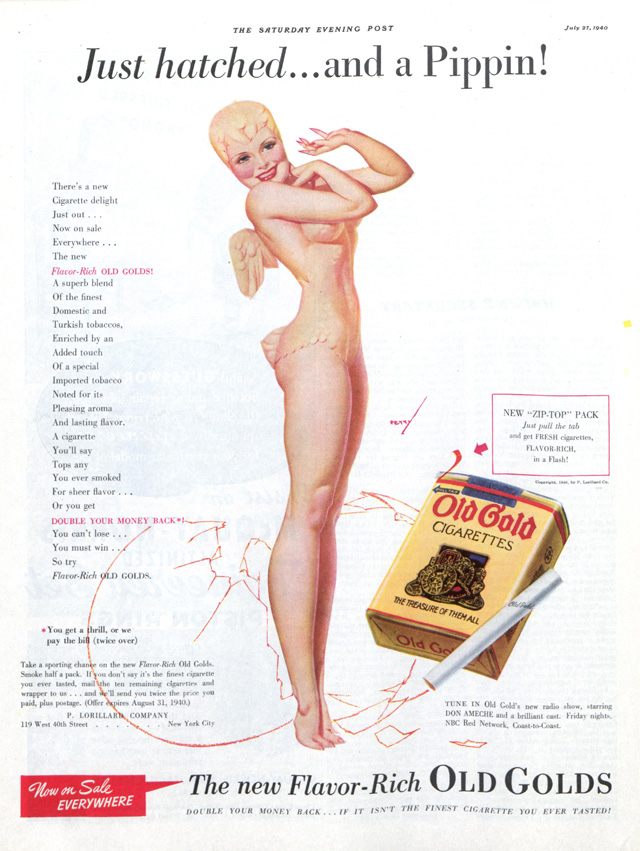

Vintage Ads: Selling Cigarettes with Sex

Sex sells. Desirable women, rugged men, and suggestive slogans have all been a part of advertising for more than a century. This collection of vintage cigarette ads reveals some of the ways tobacco companies used sexual themes and risqué imagery to sell cigarettes.

The tobacco industry began using such tactics in the 1880s when they began printing pictures of women in costumes on the piece of cardstock used to hold the shape of the cigarette pack — a precursor to baseball cards.

Duke, Sons & Co. was the leading cigarette brand in the 1880s and early 1900s. The cardstock images they included in their packages became collectors’ items.

Headlines in tobacco ads were often double entendres, inviting readers to decide whether they were talking about their product or the person pictured in the ad.

Tobacco companies often chose attractive women to star in their ads to attract the male audience. Although sexual references primarily targeted men, they also lured women.

According to studies done in 2007 by Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising (SRITA), women were manipulated to believe that if they smoked cigarettes, they would be sexier and more attractive to men.

SRITA also found that if tobacco companies used slim women with fashionable clothes, women would be enticed to smoke.

Research shows that sexual imagery tends to grab consumers’ attention more quickly than a non-sexual ad and holds their attention longer. A study done by the University of Georgia (UGA) concluded that sex really does sell.

A UGA researcher explains that “people succumb to the ‘buy this, get this’ imagery used in ads.” They subconsciously believe that buying the product will make them as attractive as the people portrayed in the ads.

So what exactly were tobacco companies selling? An image, a fantasy, sex. And maybe a cigarette or two.

Is the Sexual Revolution Over Yet?

The sexual revolution — or at least some version of it — was televised.

In the 1970 film Zabriskie Point, Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni attempted to capture the collective U.S. sex drive in a series of striking and surreal images: young people engaging in an orgy in the Death Valley dust, explosions of branded domestic items set to Pink Floyd. The film was an utter failure, but it gained cult status and a recent DVD re-release. In hindsight, Zabriskie Point rendered the countercultural zeitgeist of the ’60s boldly and accurately, or, at least, how many have come to imagine the “free love” mythology of the period.

Whether or not dazed hippies frequently made love on mountainsides might be immaterial, because, as it turned out, the revolutionary part was just getting started.

At the time, it seemed as though the whole country might become a bastion of free love and the Pill, with stoned coeds and university feminists declaring a new age (the Age of Aquarius?) in which — perhaps — writhing naked bodies would cover the land from sea to shining sea. But the sexual revolution wasn’t a one-way magic bus ticket to the orgiastic bacchanal portrayed in pop culture and feared by mid-century pearl clutchers. Its effects were actually much more profound.

“The revolutionary part wasn’t necessarily the frequency of sex, but that the factors undergirding sexual activity changed.”

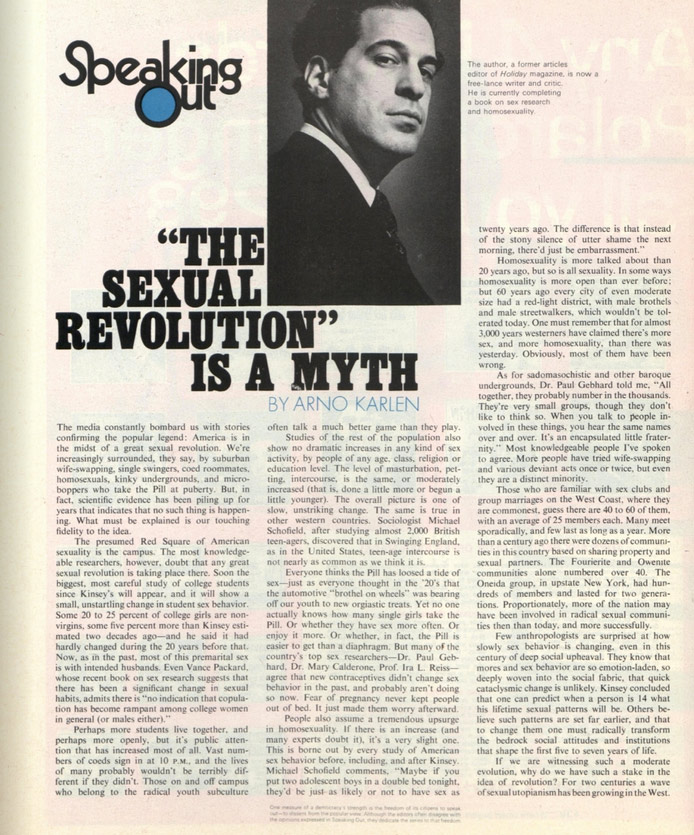

Anyone who was conscious during the ’60s would tell you that the times were a-changin’. The new availability of birth control, reshaping of gender roles, and a burgeoning gay rights movement gave many Americans the idea that the term “revolution,” preceded by the qualifier “sexual,” was an apt characterization of what they saw around them, for better or worse. But it was never about everyone having sex all the time. If that was your goal, then the revolution fell short. At least that’s what future Penthouse editor Arno Karlen thought.

In December of 1968, Karlen took to the pages of The Saturday Evening Post to voice his incredulity of the so-called sexual revolution. Karlen claimed that mounting scientific evidence refuted the existence of a grand American sexual awakening, and he backed it up with studies and statistics.

Karlen’s argument centered on the idea that “four-letter words and mini-skirts don’t mean people act very differently in bed.” In his 1968 article “‘The Sexual Revolution’ Is a Myth,” he cites the humble rise in sexual activity during the sixties (some five percent more of college women were non-virgins), and he poo-poos the effect of the birth control pill, stating that “new contraceptives didn’t change sexual behavior in the past and probably aren’t doing so now.” He also speculates on the unchanging nature of homosexual activity and non-monogamy, or swinging. “I object not to the idea of sexual revolution but to the illusion it has taken place,” Karlen writes. “We need one badly — a real one that will allow people to live healthy, expressive sexual lives without legal penalties and social obstacle courses.”

Karlen believed the sexual revolution was a superficial, media-created non-event of nothing more than slutty outfits and dirty words. The problem is that Karlen came to the party just a bit too early. In 1968, the revolution was just getting started, and mini-skirts were just the beginning.

In his cultural analysis, Karlen might have benefitted from just a few more years of perspective. Six months after the article, the Stonewall riots took place in Greenwich Village. Then, the National Center for Health Statistics found that premarital sex among women had gone from 52 percent occurrence in the early sixties to 72 percent in the early seventies. By 2003, a public health report stated plainly that “Almost all Americans have sex before marrying.”

With a little more time, Karlen might have seen that the revolution did deliver — or at least the social obstacle course of sex before marriage was partly dismantled.

Harvard teacher and history scholar Dr. Nancy Cott says that it’s impossible to discuss the sexual revolution without noting its impact on the concept of marriage in American life. Cott, who has written extensively about issues around gender, relationships, and feminism, and remembers the sexual revolution firsthand, says, “The sexual revolution erased marriage as the bright line between sex that is okay and sex that isn’t okay. It did that legally and socially. That was a major change.”

In the mid-twentieth century, most people would not dare live with a partner out of wedlock. Today, such arrangements are much more common (if not always approved of). “Maybe it’s hard to see how important the presence of marriage was as a social institution, but it was,” Cott says. “Now, maybe you do or don’t marry, or you divorce, and that happens all of the time.” Just around half of U.S. adults are married in recent years, compared with 72 percent in 1960.

Ironically, the same revolution that freed some people from the shackles of marriage allowed other people to put them on for the first time. Dr. Cott wrote several amicus briefs for court cases regarding the same-sex marriage question in the 2000s. While many actors in the sexual revolution deemed the constraints of marriage to be oppressive, Cott says the marriage equality movement was more about civil rights: “You have to be able to opt in to say ‘I am opting out.’”

Another accomplishment of the sexual revolution, according to Cott, was reversing a set of Victorian beliefs that women were sexually dormant until they fell in love with a man who “awakened” their sex drive. “It’s striking to me how long-lasting and deep interpretations have been that women are not as sexually-driven as men.” she says.

Questions surrounding sexuality have long been the focus of Indiana University’s Kinsey Institute, where Dr. Justin Garcia works as an evolutionary biologist and sex researcher. He agrees that the sexual revolution changed the way people approach copulation, saying, “My guess is that more heterosexual couples today are having more conversations about mutual pleasure and consent than 60 years ago. The revolutionary part wasn’t necessarily the frequency of sex, but that the factors undergirding sexual activity changed.”

Garcia, who serves as an advisor to Match.com’s Singles in America study, says that more sex may or may not make people happier, but more consensual, safe, pleasurable sex does.

While we have widespread availability of birth control pills, tacit approval of sex before marriage, and the trend toward communication and mutual pleasure, confoundingly, people seem to be having less sex. Garcia, however, wouldn’t consider it a departure from the arc of the sexual revolution: “In a real sexual revolution, you would expect, perhaps, that sex will only happen when both partners desire it. You might even predict a decrease in frequency if other things are going on, like positive changes in gender egalitarianism,” he says.

The Kinsey Institute researcher claims that one could argue that we’re still in a sexual revolution, since issues around sexual and gender diversity, contraceptives, abortion, and women’s rights are still relevant. “There was a historical moment that we often refer to as the sexual revolution, but, in practical terms we’re still in one. We’re still looking at major shifts in how we understand issues around sexuality and people’s sexual lives and behaviors and how society deals with that,” Garcia says.

To get to the heart of what the sexual revolution means, we need look past the psychedelic-fueled mountainside ménage à trois and into the common sexual desires of everyday people. Non-monogamy and homosexuality existed in America long before the ’60s, and women did experience orgasms prior to the Vietnam War. Our willingness to allow “people to live healthy, expressive sexual lives” is an ongoing national project with unclear beginnings, yet decidedly evident results.

Featured image: Zabriskie Point (1970), Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer