“How We Marched through Georgia” — A Union Soldier’s Tale of the Civil War

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the May 20, 1961, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

Robert Hale Strong was just 19 when he marched off to the Civil War with the 105th Illinois Union Volunteer Infantry and lived through grim fighting in the Georgia-Carolinas cam- paign. In his letters home, he told with brutal realism but unflagging good humor of humanity under fire and American courage of both sides. The following article is excerpted from that manuscript, later published under the title A Yankee Private’s Civil War.

* * *

We were under fire every day for about a month between Buzzard Roost and Atlanta, Georgia. I don’t mean that we were in a big battle every day, but were in a fight or skirmish on the picket line, always firing at one another. All the way to Atlanta was a series of fights. We did not always have it our own way; the Rebs were as stubborn as mules.

One time the enemy’s range was extra good, I remember, and their shells and bullets kept us dodging busily. You must understand that it was no real use to dodge, as the balls would either hit or pass us quicker than we could dodge. Old Col. Dustin saw the boys dodging, and he sung out, “Stop that dodging. Stop it, I say!” Just then along came a shell pretty close to his head. He was on horseback, and he bowed his head almost to the saddlebow. The boys laughed, whooped, and yelled. The colonel straightened up and said, “Well, d—n it, dodge a little, then.”

That same day, it seems to me, we experienced the heaviest musketry and artillery fire that we had all through the war. We fought them all day. They were on an elevation, and it is a fact that after we were relieved and started to the rear we could see round shot roll along the ground with enough force to tear off a man’s foot, as one negro discovered who tried to stop one with his foot. About then I found I had lost my knife and my pocketbook. I started to go back to the rail fence where we had been, to look for them. When I got nearly there, I found the Rebs had taken possession, and I lost all desire to recover my property.

The second day of the fight, we had been advanced to- ward the enemy in the shape of an upside-down V, with our troops at the point and Rebs on each side and in front. We were in timber. Across an open field we could see the Rebs massing about 80 rods away for a charge. The 102nd Illinois, armed with Spencer rifles, seven-shooters, were deployed in front of us as skirmishers. As the Rebs would advance, the 102nd boys would open on them with their seven-shooters and pretty soon, back they would go, only to rally and try again. We could hear their officers cursing them for cowards to run from nothing more than a thin line of skirmishers.

Shortly after they quit coming for us, Gen. Joe Hooker rode up, looked around and asked, “Who has command of these troops?”

Brig. Gen. William T. Ward said, “I have, sir.”

“D—n you, sir,” says Hooker, “don’t you know you have got these boys in a trap? The enemy are on three sides of them and prepared to charge on each side. Recall everybody but skirmishers and tell them to fall back quietly — don’t let a tin cup rattle to tell the Rebs that we are moving.” So we got out of that, but it was a close call.

During the first part of the Atlanta Campaign, I messed with Matthias Stephens and Ernst Hymen, both good, quiet, religious boys. One night, after advancing and driving the enemy all day, my mess had gone to our pup tents, and we were talking about the probability of a battle on the morrow. I used some strong language about the enemy and about our having to work so hard on short rations. Stephens checked me, saying, “Don’t talk so. Some of us will be killed tomorrow in the fight.”

Well, early the next morning we began a running fight, with the enemy falling back slowly. In advancing, we took advantage of all the shelter we could get, behind logs or stumps. My position was on the right of the company, being one of the tallest boys, but of course in that kind of advance ranks are not kept very true. It got to be a pretty hot fight. I heard someone call out, “Strong — Bob Strong!”

Before I could answer, someone else says, “The man call- ing you is out there in front of the line.” I saw the hit man shudder and lay his head down on his arm. I knew he undoubtedly was killed, for if only wounded he would have called further for help.

The Rebels refused to be driven any farther for hours. It was nearly sundown when they pulled out and we advanced. Our boys all gathered around the fallen man in our immediate front. Sure enough, it was one of my messmates, Ernst Hymen. He was shot directly through the top of his head and probably never knew what hurt him. Our orders were to push on after the enemy, but a few of us remained, dug a pit and wrapped Ernst in a blanket in his lonely grave.

One day during a battle our brigade was ordered from center around to the right of the enemy. We marched just behind entrenchments filled with Yankees and across a field where we could see the enemies’ breastworks. We watched them working their artillery, with their shell and shot whistling over and among us. At the rear of the regiment were the major and Dr. Potter, brigade surgeon. If we saw a shell coming low, the men in line with it would lie down. One came along, striking the ground and rebounding. Dr. Potter with others was directly in line. Some lay down. Dr. Potter laughed at the boys. The shell struck the ground just in front of him, rebounded and took the top of his head off. As it hit him, a little puff went up from his head, and he fell dead. Then the shell struck the ground a few feet beyond him and stopped, with the fuse hissing. One of our boys ran to it and poured water from his canteen onto the fuse, putting it out and thereby probably saving many lives at the risk of his own.

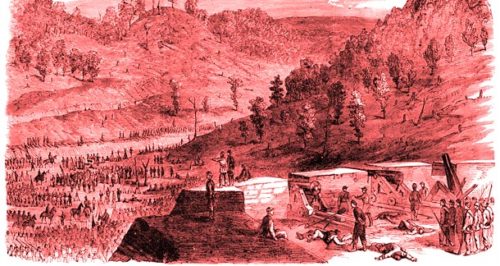

At that point we were ordered to support a battery. As we came in sight of the battery, the Rebs, in three lines, They were about as near it as we were. We went on the run to save it. How those gunners did work those guns! At every discharge we could see holes open in the Johnnies’ ranks, but they closed up and kept on coming. When we reached our place behind the guns, the Rebs were not more than 100 feet away. Even in our hurry and great danger we handled our rifles as if on drill. Every man reached his place, pointed toward the enemy, and began firing. The Rebs were not more than 60 feet away. They went down like a boy shooting into a flock of blackbirds. It checked the charge, and the Rebs fell back. Our boys sent up a big cheer, then the battery boys had to shake hands with such of us as they could reach.

The enemy infantry having pulled back, their artillery began firing at us. Our battery returned the fire. We of the infantry lay down so as not to catch any more of the shot and shell than we could help. It was said there were 700 dead and wounded in our front. I know it looked as if we could walk over men without putting foot to the ground.

After our battery opened on them, the enemy scattered. Then we were ordered to do a thing that I thought then, and think now, was a foolish, foolhardy thing. Our music struck up, and with arms at “shoulder” we marched in a solid square out into that open field, the bands playing Be- hold the Conquering Hero Comes. There we stood at “rest,” supposing all the time that the Rebs would open fire, as we were in plain view of them.

We lay down, expecting we were now safe for the rest of the day. Scott was marching up and down in front of us, declaiming some funny piece to amuse us, when the Rebs began to shell us. Scott kept on declaiming, and the boys kept on laughing. Then, with a heavy shock, a big shell struck within ten feet in front of our company and buried itself in the ground. We just held our breaths, expect- ing it to explode. Scott threw himself on the ground. I flattened myself out on the ground, until I seemed to have made a hole in it. May- be you can imagine what the suspense was, waiting for some of us to be killed. Of course, all this happened quicker than you can read it. After perhaps a minute Mark Naper lifted his head, his eyes big as saucers, and said, “Why don’t the — thing bust?” That made us laugh. As far as I know, the shell never did explode.

We became so used to noise — the firing of guns and can- non, the yelling and cursing of teamsters and artillerymen, and the blaring of bugles — that when permitted we would lay down and go to sleep amid it all and only our brigade bugle call would rouse us.

On the famous march from Atlanta to the sea we traveled light. Three days’ rations were issued to each man. Fifteen days’ rations for each man was put into wagons. We were ordered to form forage squads and to live off the country or go hungry. We did both at times, often having nothing to eat for 24 hours. Commonly our rations consisted of sowbelly — fat salt pork — and hardtack. We got four large hardtacks — crackers so dry as to resist all action of the weather — as a day’s ration. We had coffee, too, and sometimes sugar. At times we would draw what was called desiccated vegetables, a mixture of peas, beans, cabbage, turnips, carrots, onions, and beets, with grass to hold everything together, and dried and pressed. A piece an inch square would swell and swell into all the soup a man could eat. It was not to be despised. Our coffee generally was parched. Sometimes we would boil the berries whole, save and dry them later and trade them to the natives for corn bread, milk or butter. It was a fair exchange for some of the pies we got. Nobody but a soldier or an ostrich could digest them.

During this time we could draw no clothing, and ours was nearly worn out and did not pretend to cover our nakedness. I have foraged women’s shoes and stockings and worn them too. The mountain women had good-sized feet and wore heavy calf shoes, so I did not do so bad.

Our orders, while out foraging, were to capture all Confederate soldiers, seize all horses, burn all cotton and all Rebel government stores, but not to molest any citizens who remained at home and to respect all private property except for horses, mules and forage for man and beast. As far as I know, the order was respected.

Many times in Georgia we and the Rebs — after skirmishing and shooting at each other all day — arranged our own private truces. Once we stripped off, swam to a sand bar in the middle of a little river and traded our coffee for their tobacco. When we lay for a time along the Chattahoochee River, we agreed not to fire at each other except by officers’ orders and, if such orders were given, to notify the other side before firing. We told each other across the river, about 20 or 30 rods wide, that if we did kill a man once in a while it would have no effect on the war as a whole, that it was all nonsense.

One evening just before sundown, as both sides were taking it easy, a Rebel officer galloped up on his horse and began cursing and swearing at his men for not shooting the d—n Yankees. “Talking with them, are you?” he yelled. “Begin firing and shoot the hell out of them.”

We could hear everything he said and took up our guns. The Rebs yelled, “Hunt your holes.”

Little Charley Hapgood of our regiment, a splendid shot, says, “I’ll fix him.” We all stood watching as Charley fired. The Rebel officer threw up his arms and fell dead.

We cheered and cheered and called, “Say, Johnny, is it time to hunt our holes yet?” and they said, “No, he was a damn fool anyway and deserved what he got.”

Later on I also had some trouble with one of our own officers, a general, no less. In our corps, the Twentieth, one division consisted in part of Eastern troops under Maj. Gen. John W. Geary of Pennsylvania. Geary was a martinet, much stiffer with his boys than we of the West could stand. He frequently threatened to arrest us while foraging and confiscate our forage. He was cruel, too, in exacting full discipline of his men. I have many times on the march passed his camp and seen men with a cord tied around their thumbs, standing on tiptoe with their arms stretched above their heads and their thumbs tied to the limb of a tree. It was an ugly sight, and more than once our boys cut the men down.

My run-in with Geary came one morning when I was walking back from the advance guard with a message. About halfway, Geary and his adjutant rode up. I saluted and stepped aside to let them pass. Halting his horse, he asked, “What in hell and damnation are you doing here?” I told him. “You’re a damned liar, you are skulking,” he replied. “About face and go with us until we meet your command.” I told him that he was mistaken, that I was obeying orders already and could not obey him. He swore he would cut me down and drew his sword. His adjutant moved to draw a pistol.

I cocked my gun and said, “Sew, or I’ll kill you both where you are.” I then repeated my story and begged their pardon for my conduct.

Geary remarked to the adjutant, “I expect we were too fast,” and to me, “I believe you, and I am sorry for my anger.” He went one way, and I went the other.

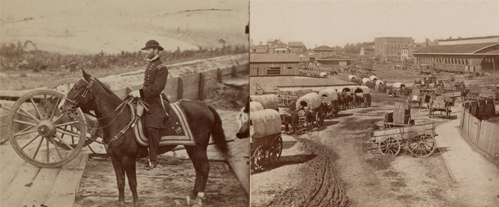

Picket or guard duty was fun for the boys, for they not only got away from camp but had a chance to catch up officers. One time I stood sentry close to the enemy lines. Oh, how it rained! The mud was half knee-deep. Just as the morning began to get gray, I saw out in front of us a man slipping along from tree to tree, followed by several more. He passed post after post until he came to mine. He had on an old slouch hat, pulled well down over his face to keep the rain off, and a rubber blanket, high boots with spurs and a sword at his side. Well, I says to myself, it is Sherman, but he must come in like anybody else.

As he got in front of me, I called to halt him. At first he paid no attention, so I cocked my gun and says, “Halt! Come in or I’ll fire.”

Sherman and his staff put their hands up and came up to me, all of them. Sherman shook hands and said this was the only post but one to halt him, and that other posts let him go as soon as they knew him. I said, “Our orders were to halt everything that moved in our front.”

He said, “You did right,” and said he was out examining the lines. When he left, I saluted him, and he and his companions returned the salute. He was a nice general. Wherever he went, the boys would give three cheers for “Old Tecump” or for “Billy T,” and he would grin and wave his hat to us. He could joke too. There were lots of foreigners — Germans, Irish and others — among our troops. Once when the Rebs stopped us near Atlanta, I heard that Sher- man shouted command-like, “Attention, creation! Forward by nations and flank them!”

While marching through the public square at Smithfield, North Carolina, we saw Sherman seated on a big block. Behind him was an elevated platform with a rail, and in the center of it a tall and stout post with rings and cords attached. The platform was the auctioneer’s stand where he knocked off slaves to the highest bidder. The post was the whipping post. Just as we came up to Sherman, he cast his eyes toward this platform and waved his hand toward it. In just one minute, we had it torn down. Someone struck a match, and the whipping post was no more.

As we hurried by him, we asked, “How’s that, general?”

He grinned and said, “Good job.”

In Richmond a large section had been burned, and for blocks and blocks the weeds and grass were growing where houses had been and between paving stones. It was a picture of desolation and ruin. The country beyond Richmond was so bare that orders were very strict against foraging, but the boys had innumerable excuses when found with a pig, goose, or chicken. The goose tried to bite, so had to be killed. The chickens crowed to the tune of Dixie, so had their necks wrung. Pigs squealed for Jeff Davis, and soldiers could not stand that!

Then we marched for hours across the field of the Battle of the Wilderness, which lasted for days. We could tell by the graves how far charges went, and where Rebels and Yankees had stood. The dead were barely buried. It seems terrible to think of it now, but the boys would kick a skull out of the way as indifferently as if it had been a stone. Some would pick up a skull with a bullet hole in it and speculate about it.

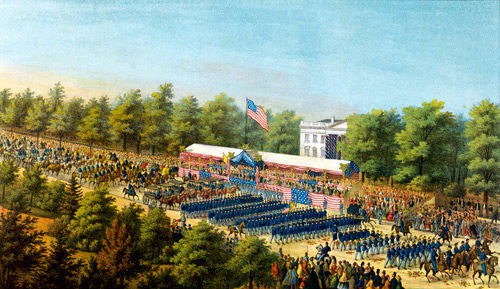

At the end of it all the Army of the Potomac, in white gloves and collars, with new uniforms, with their buckles and eagles bright as stars, paraded through Washington past the grandstand which contained President Johnson, generals Grant and Sherman and many others. The next day we of the West had our parade. We had been ordered to draw new uniforms. At the last moment our regiment packed them away. Instead of smart knapsacks, we had our blankets rolled up and hanging over our shoulders. We were so tanned we looked almost black, with worn uniforms and all kinds of hats, but our guns were always clean and bright. There was not a collar or pair of white gloves among a thousand men. There was as great a contrast between us and the “feather-bed soldiers” as possible. But when we halted in front of the reviewing stand, everybody cheered like mad. We stood there, as indifferent as an old maid to the voice of flattery.

“How We Marched Through Georgia,” May 20, 1961