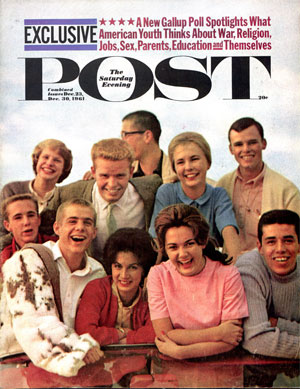

Was Young America Too Nice in 1961?

Probably every generation of American adults has been able to complete the following sentence: “The trouble with kids today is …” America’s grown-ups, it seems, are continually fretting over the next generation, which seems so rebellious, reckless, and impatient to give the world a complete makeover.

But in 1961, some youth-watchers worried about the exact opposite. The youngsters of that decade were unusually cautious, well behaved, and ready to compromise with the world. At least that was conclusion of a Gallup poll published in the Post that year.

Hoping to understand a “cross section of our future,” Dr. George Gallup and Evan Hill interviewed 3,000 people between the ages of 14 and 22. What they discovered had them worried. The rising generation, they concluded, were “bland… cautious, self-satisfied, secure, and unambitious… nice little boys and girls who are just what we asked them to be.”

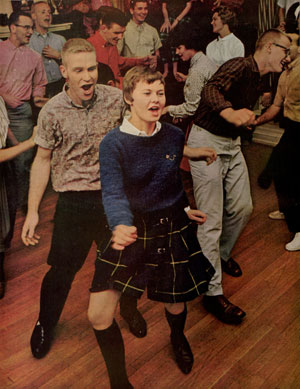

Born between 1939 and 1947, most of these young people fell into a group now called the Silent Generation (those born between 1925 and 1945). Having been raised by parents who endured the Depression and a world war, these youngsters valued stability and security. They were eager to fit into the status quo and protect their comfortable way of life. They were unlikely to rebel or get involved in crusades of any kind, wrote Gallup and Hill. They were generally satisfied with life and themselves. “Almost 90 percent are satisfied with the kind of person they have turned out to be (20 percent are ‘extremely satisfied’).”

With little interest in changing the country, over 80 percent had no intention of entering politics. Perhaps this is why there has been no president from the Silent Generation.

Risk-averse and conformist, the generation, as Forbes columnist Neil Howe describes, “tiptoed cautiously in a post-crisis social order that no one wanted to disturb.” The Silent Generation settled into adulthood quickly by marrying and having babies “younger, on average, than any other generation in American history.”

The hunger for security was also due to the likelihood of war with Russia. The young interviewees in 1960 told Gallup and Hill that they expected to see nuclear attacks in their lifetimes that would destroy entire populations. Living with such expectations, they kept their heads down and enjoyed what they could, while they could.

The typical young man of this generation, according to Gallup and Hill, had modest goals: “two or three children and a spouse who is ‘affectionate, sympathetic, considerate, and moral’; rarely does he want a mate with intelligence, curiosity or ambition. He wants a little ranch house, an inexpensive new car, a job with a large company, and a chance to watch TV each evening after the smiling children are asleep in bed.”

These young people believed in getting along. They were even willing to compromise with enemies rather than risk war. “If this country should become involved in another limited war, such as Korea,” the pollsters asked, “do you think we should try to end it on the basis of compromise, or should we fight it out even if this means getting into an all-out war?” The kids favored compromise: “More than three-fourths of the girls and almost 60 percent of the boys say they would be unwilling to risk war.”

What this generation wanted were good, steady jobs (only 10 percent of the youngsters said their life goal was to achieve fame, recognition, or wealth). Normally, such modest ambitions would yield modest returns. But the comparatively small number of children in this generation created a smaller work force when they entered the job market. With America’s economy booming in the postwar years, companies had to compete for workers, which drove up wages. As a result, the Silent Generation entered retirement more prosperous than any generation that has followed them.

The lack of ambition in these young Americans bothered Gallup and Hill. They worried that the future of the country, and the world, had been placed in the hands of “indifferent and distressingly bland” Americans who displayed “compromise, conformity, and intellectual poverty.”

In hindsight, their fears about the next generation seem wildly exaggerated. True, the Silent Generation never developed a rebellious streak, but their willingness to compromise never threatened our national security. They firmly supported America in its long cold war with the Soviet Union. And despite what they told the Gallup interviewers, they generally supported the war in Vietnam; hundreds of thousands of them even served in the military during that conflict. Moreover, this generation challenged traditional thinking about race in America and supported equal rights for black Americans.

Like each generation, the Silent Generation made its contributions to the country. And, like other generations, failed to live up to its critics’ worst fears.