Mr. Singer’s Money Machine

When one envisions the mid-20th-century working man, certain jobs come to mind: the ad executive, the steel worker, the auto maker. One often overlooked job of the mid-century was the salesman.

The end of the war spurred a burgeoning middle class and saw the development of lots of new time-saving household devices. But in a time before the internet and big box stores, how did consumers find out about amazing new gizmos they couldn’t live without? Manufacturers hired hard-working, pavement-pounding, door-knocking salesmen to get the word out. All you needed to do the job was a little confidence, a little gumption, and a lot of perseverance.

In the July 7, 1951, issue of The Saturday Evening Post, John Kobler wrote about the juggernaut that was the salesforce for the Singer Sewing Machine Company. At the time, it deployed 40,000 – 40,000! – “Salesmen-and-Collectors” to all corners of the globe to sell its machines. According to Kobler, the company spared no effort to do so.

During the century since Isaac Merritt Singer invented the machine which has sustained the world’s farthest-flung commercial empire, they have penetrated lands wilder than the Amazon region and survived perils deadlier than any braved by Mordecai Cobb. They have canvassed practically every inhabited spot on earth, from igloo settlements above the Arctic Circle to Pygmy kraals in Equatorial Africa. They have been buffeted by hurricane, earthquake and flood; plundered by bandits, beaten up by xenophobic mobs; jailed, amid revolutions and wars, as enemy aliens.

The article follows the exploits of one Singer salesman in particular: Omer Abu-Baker, who braves Bedouin raiders, rock-throwing baboons, and precipitous mountain trails to sell sewing machines in Yemen. Equipped with bedding, field rations, a first-aid kit, and two pistols, Omer makes his way around the country, patiently negotiating with imams, waiting for payment, and finding free agents to sell even more machines. Kobler writes that “At last reports, business there was extending nicely, and Omer has been recommended for a raise.”

Embedding salesmen globally was just one of Singer’s pioneering strategies. The company also led the way in the introduction of mass marketing and pioneered the use of installment plans and rent-to-own.

Financially, Singer was doing very well for itself. In 1950, Kobler reported that the stock was among the few securities selling at more than $300. Net profits that year were $18.8 million.

The company also innovated when it came to the machines themselves:

Singer also gets a good many suggestions for sewing-machine attachments which sound as though they had been conceived in delirium. They have included a “squatorganomotor,” a combination of harmonica and player piano, to soothe the seamstress with music as she sews; a fan to cool her; an atomizer to spray her with perfume; a fly exterminator; a shoe shiner; and, inevitably, a perpetual-motion apparatus.

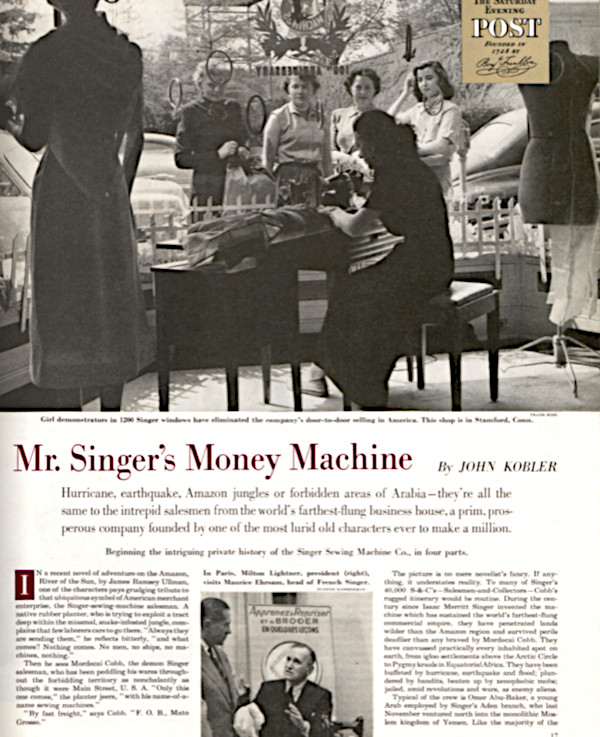

But in the U.S., the door-to-door salesman was already going the way of the buggy whip. After World War II, Singer ended house-to-house canvassing in America in favor of “sewing centers.” The rest of Singer’s story for the second half of the 20th century is a common one, filled with diversification, corporate raids, and mergers. Today, Singer is part of private company SVP Worldwide and still makes sewing machines. It has offices in Sweden, Switzerland, Italy, and the U.S. Its current sales presence in Yemen is unknown.

Featured image: Photo by Frank Ross (©SEPS)