Vintage Ads: The Century-Long Search for a Good Night’s Sleep

For as long as insomnia has plagued our great nation, entrepreneurs have been hawking cures from pills to pillows. Today’s weighted blankets and ASMR were yesterday’s snore balls and Ovaltine. In spite of our best efforts, a report from the National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research estimates that overall sleep time in the U.S. has decreased by 20 percent in the last 100 years. Though our approaches to sleeplessness are ever-changing, the pages of the Post prove that, for more than a century, manufacturers have been thinking up new ways to woo people into slumber — or at least make a few bucks trying.

(Click to Enlarge)

(Click to Enlarge)

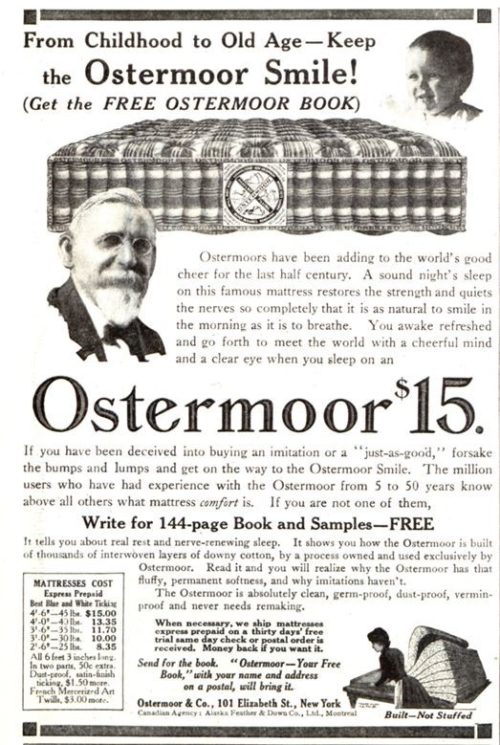

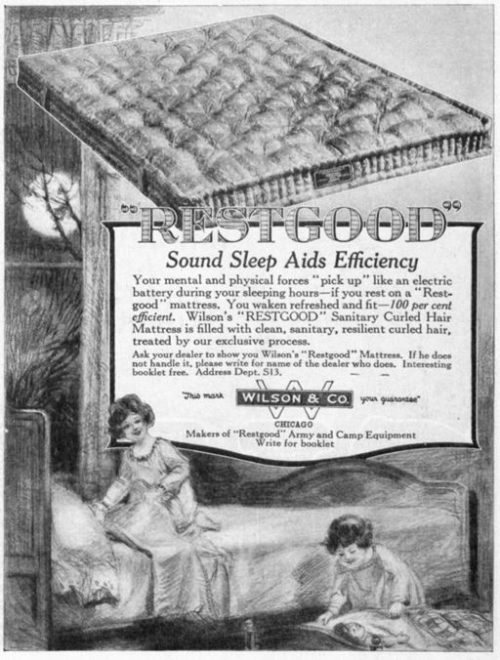

Before the mattress innovations of the 20th century, brands like Wilson & Co. and Ostermoor boasted their top-notch quality beds made from cotton and… “curled hair”? That’s right, the Restgood Sanitary Curled Hair Mattress — from the company that makes your tennis rackets — was stuffed with animal hair. The meatpacking man Thomas Wilson broadened his manufacturing focus in the early century to include sporting goods, luggage, violin strings, and mattresses. All of these products reduced waste from the slaughterhouses. Try not to let it keep you up at night.

(Click to Enlarge)

(Click to Enlarge)

(Click to Enlarge)

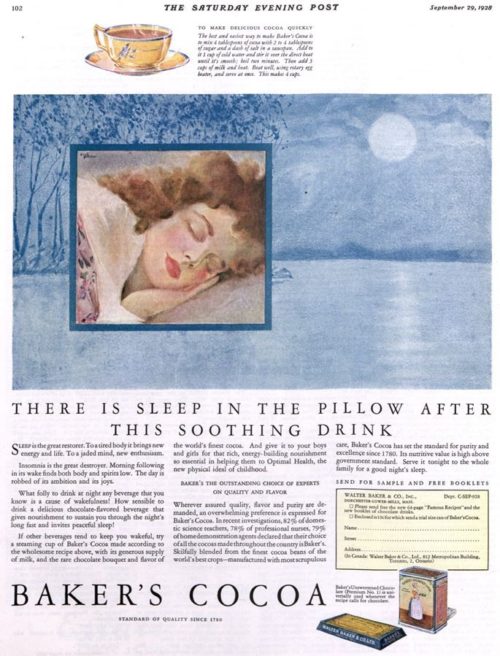

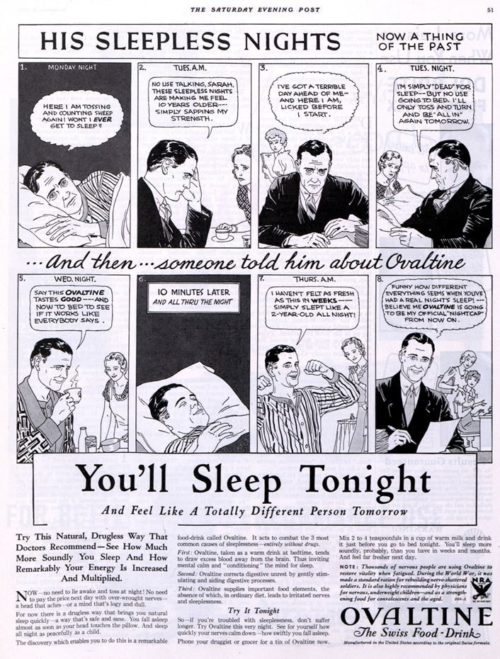

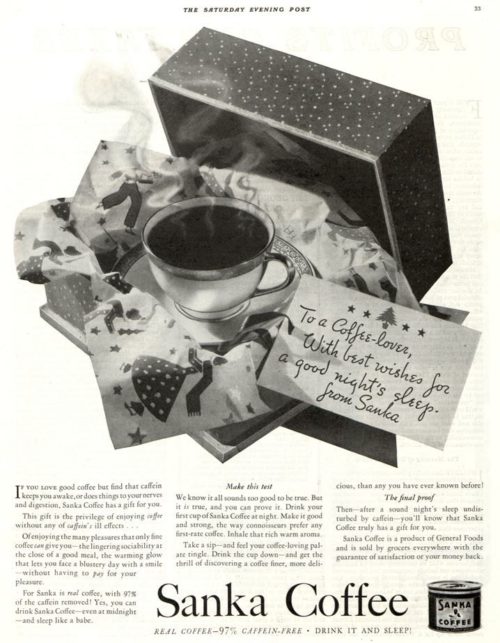

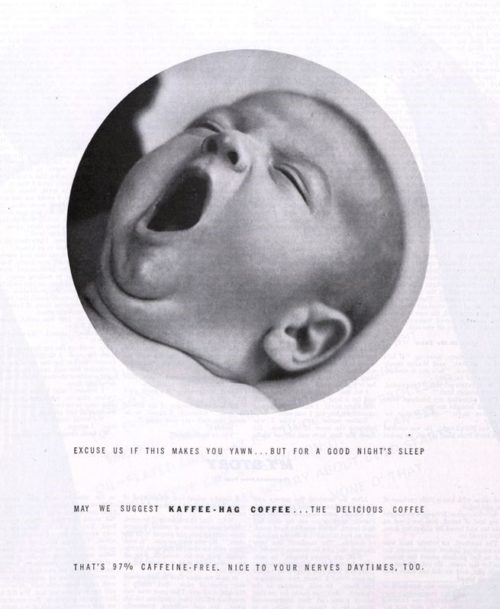

Insomnia was “the great destroyer,” and the remedy could be steaming hot beverage. Malted beverages, hot cocoa, and even (decaffeinated) coffee were promoted to calm the mind and aid in digestion, affording drinkers a restful night and nerveless morning. Comic advertisements like Ovaltine’s appeared often in the early century, reflecting common anxieties around city-living and careerism. Without fail, the product in question would allay maladies, like sleeplessness, that affected the man of the home and, in turn, the whole family.

(Click to Enlarge)

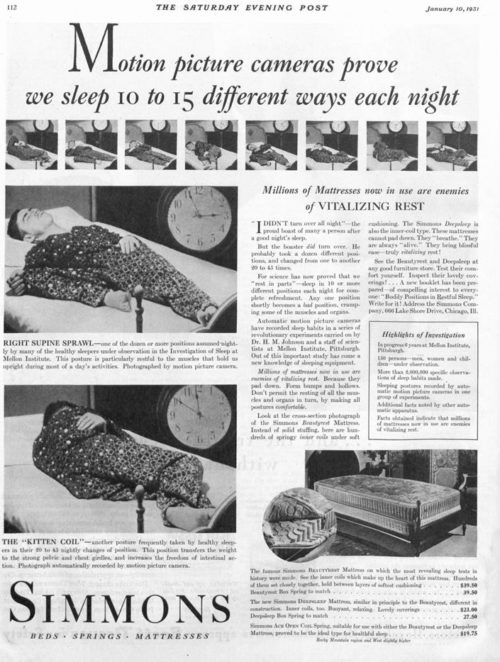

Though innerspring mattresses had been in existence for decades, they gained popularity in the 1930s. “They ‘breathe.’ They are always ‘alive,’” one Simmons ad claimed. Less lumps and a longer life meant the bed would remain a winner for consumers for years. Even now, a spring mattress is a top choice for all kinds of sleepers.

(Click to Enlarge)

(Click to Enlarge)

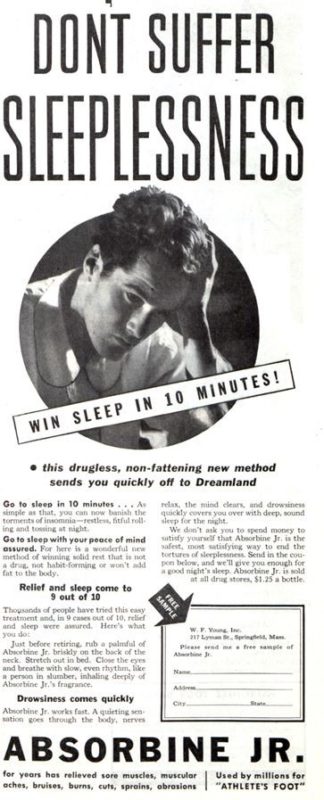

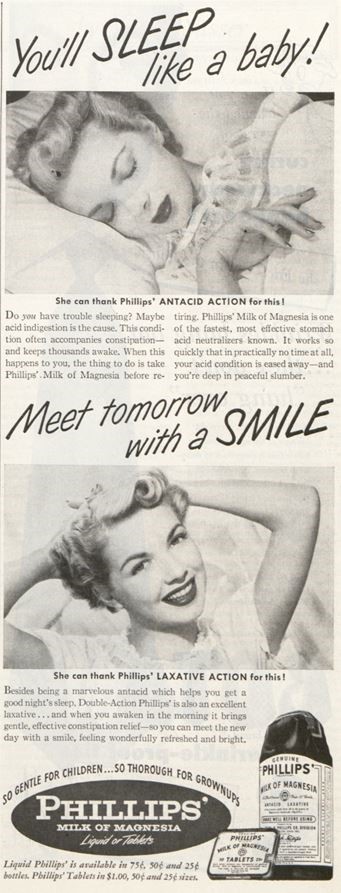

Originally created for work horses, the topical pain reliever Absorbine Jr. was easily branded as a sleep aid, since back pain could be blamed for many a sleepless night. It appealed to the desire for a “natural” remedy with “no doping” involved. And if a lack of z’s could be blamed on indigestion, perhaps Phillips’ milk of magnesia was the cure.

(Click to Enlarge)

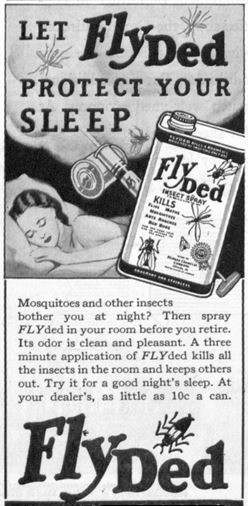

Even before the glory years of DDT, insecticides were peddled to keep bugs out of our way. The bedroom was a place where gnats and mosquitoes were most unwanted. What’s the use of buying that expensive curled hair mattress if flies are buzzing around it all night?

(Click to Enlarge)

(Click to Enlarge)

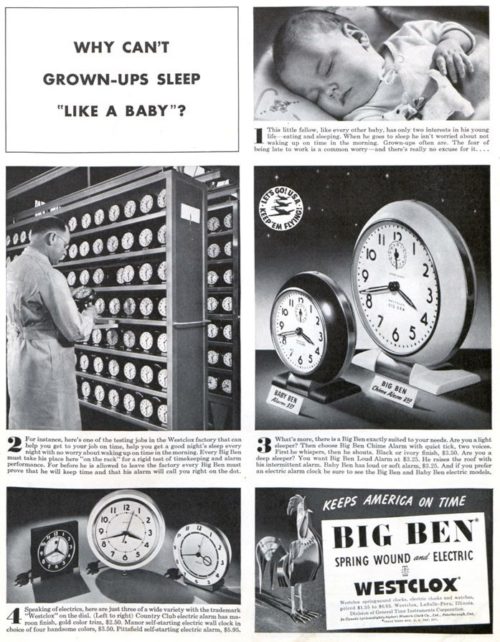

Oh, to attain that elusive slumber and to “sleep like a baby.” Nevermind that most babies wake up shrieking every three hours to be fed. Still, the peacefulness of a sleeping child evokes all we could ever want for our own shut-eye.

(Click to Enlarge)

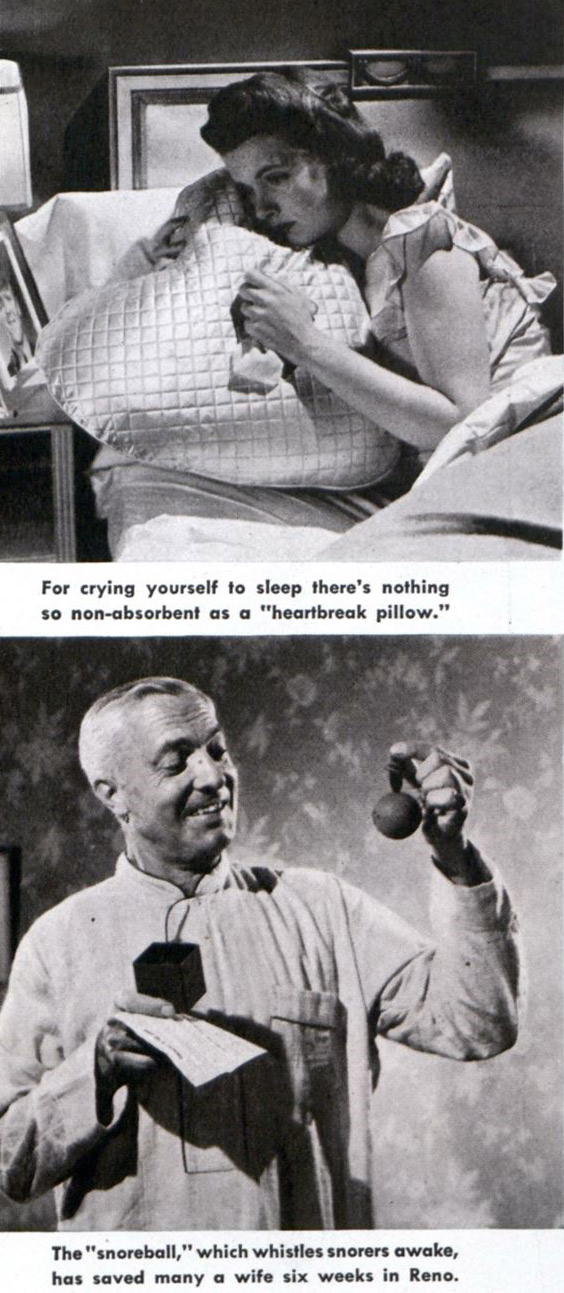

In 1942, the story “How to Get a Good Night’s Sleep” featured cutting-edge inventions and curiosities for sleep aid from the Lewis & Conger Sleep Shop in New York. “Snore balls” attached to a person’s head and whistled if they rolled onto their back. The “heartbreak pillow” absorbed a night’s worth of tears for the inconsolable. The shop even sold a “long-distance smoking tube” for customers who needed that last puff at bedtime.

(Click to Enlarge)

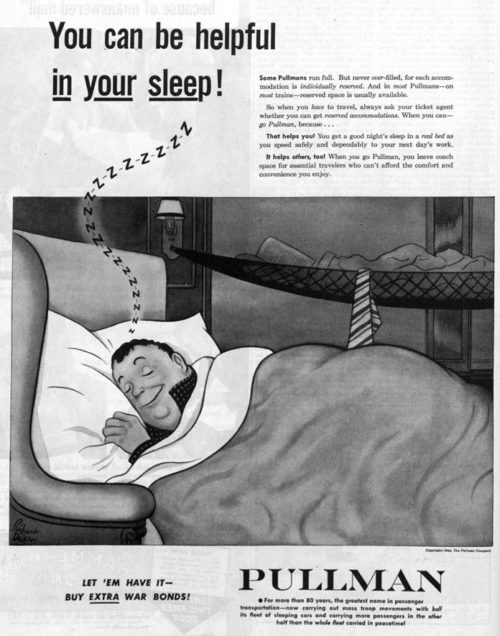

The war fit nicely into a sales pitch for companies who could claim to be doing their part. Pullman was a giant of sleeper car manufacturing and operations, and — the year this particular ad ran in the Post — the company was hit by an anti-trust suit that forced it to divest interests. Still, Pullman was a major manufacturer of small ships for the war effort starting in 1943. The Department of Justice split up the company, but it was the advent of air travel that sealed Pullman’s fate. Seventy years later, stretching on a real bed while zooming to a destination doesn’t sound half-bad.

(Click to Enlarge)

The “miracle science of electronics” was finally being put to use helping people sleep. But electric blankets had been around for decades. In the ’20s, they were a dangerous oddity used on tuberculosis patients in sanatoriums. After some development, “electronic blankets” hit the market that came with thermostats and safety features.

(Click to Enlarge)

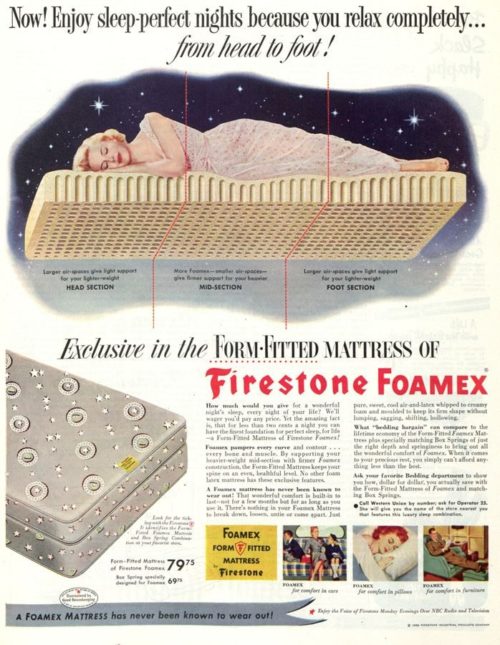

The first foam mattresses were made by the country’s trusted names in tires, Goodyear and Firestone. Before the popular “memory foam” was invented, these beds boasted “pure, sweet, cool air-and-latex whipped to creamy foam and molded to keep its firm shape without lumping, sagging, shifting, hollowing.” The familiar comforts of horse hair would lose out to new, futuristic luxuries like “foamex.” The Space Age was rapidly approaching, and a wealth of new products would dramatically reshape the way Americans lived — and slept.