The Art of the Post: Forgotten Art Treasures from World War I

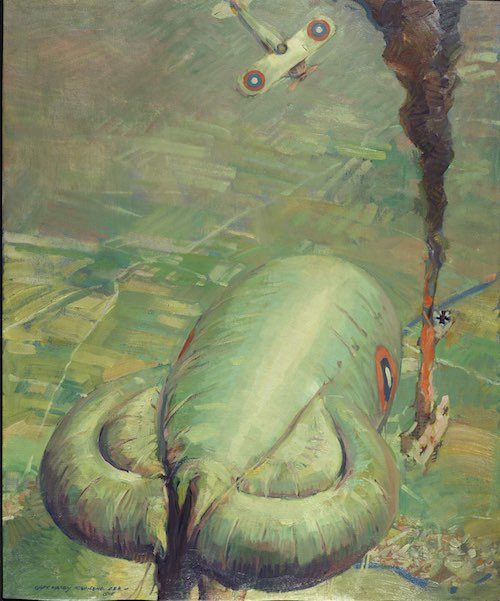

A hundred years ago, a select group of talented artists worked on the front lines of World War I, drawing and painting the human drama of The Great War. They captured the bravery and fear along with the boredom and exhaustion. But after the war ended, their eyewitness art was exhibited just once and then placed in storage at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. Pictures of the human cost of the war — of flaming aerial combat around observation blimps, of poison gas attacks, of sacrifice and dedication — were quietly filed away in dark drawers where they’ve remained ever since, for the most part unseen and unappreciated by the public.

Now with the hundredth anniversary of America’s entry into World War I, these artworks have been rediscovered and placed on display in a wonderful and fitting exhibition by the Smithsonian, a joint project of the National Air and Space Museum and the National Museum of American History.

Our story begins in 1917, when some of America’s finest illustrators left their comfortable homes and families to work on the front lines of the “war to end all wars.” One of the artists, Harry Townsend, later wrote in his war diary, “I had gotten drunk, as it were, with the future pictorial possibilities in what I saw, and what my imagination saw, in the warfare that was so soon to come.”

Eight artists were chosen to accompany the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). The artists were commissioned as officers and given free rein by both the U.S. and French military authorities to depict everything from war preparations to the terrible toll of combat in the trenches. These “artist soldiers” included Saturday Evening Post illustrators Harry Townsend, Harvey Dunn, Wallace Morgan, William Aylward, and George Harding.

Townsend’s story was not atypical. He grew up in a small farming town in Illinois but was eager to see the larger world. Townsend’s war diary records his excitement about his upcoming adventure with the AEF: “I left New York in a blinding snow, into the submarine zone with its constant alarms, and through it. My trip through London … with an air raid thrown in …. and the nervous excitement of finding myself suddenly in the war zone, for, while one realized at all times the dangers on the sea, one really felt he had arrived when he found himself in the midst of the bursting of enemy bombs and the sight of enemy planes. …”

It didn’t take long for Townsend and his seven fellow artists to witness the effect of those bursting enemy bombs: “Everywhere among the blownup trenches and in the shellholes are pieces of what were once men. Here and there, a whole or a piece of bone; here and there a shoe with a foot still in it.”

Working at an astonishing pace, this team of artists produced approximately 700 works of art. The new exhibition has divided 65 of the best of these works into five categories:

- Engineers go to war

- Life at the front

- The technology of World War I

- The battlefield

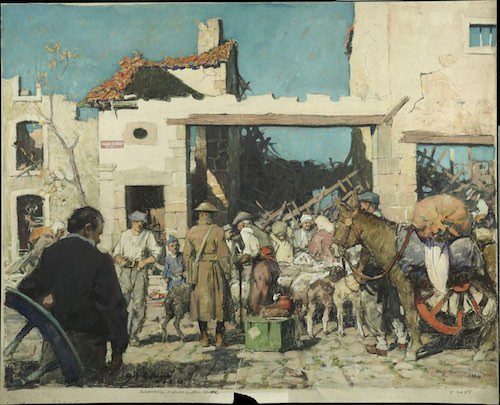

- The human cost

Some of these pictures introduced Americans to the new sights and technology of modern warfare, but the exhibition’s curator, Peter Jakab, made clear in an interview that he thought the real contribution of this art was its human perspective. “Paintings by Harvey Dunn, such as The Sentry, Off Duty, and On the Wire exemplify the idea of the exhibition. They depict the soldiers’ war experience in a powerful, in-the-moment way, offering a realistic sense of the fatigue, loneliness, and stress of war. The AEF artists were the first true combat artists, attempting to capture the soldiers’ experiences in varied and intimate ways. The exhibition reminds us that all great, sweeping historical events are made up of the actions and experiences of individuals.”

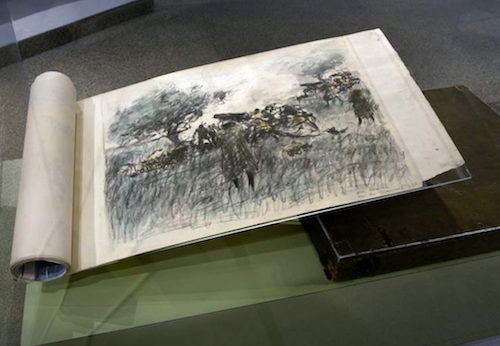

As the “first true combat artists” working in a brand-new kind of war, the resourceful eight were forced to improvise. Often they worked in rain and cold, which created challenges for their artistic ambitions. Yet they found practical solutions, so the quality and the quantity of their art remained quite high. For example, Harvey Dunn designed a protective metal sketch box that doubled as his drawing board and also contained a long roll of paper. This enabled him to continue to work seamlessly in the field.

Often the artists would sketch sights and experiences in the field and then return behind the lines to develop them into fully completed easel paintings. Many of the pictures created in the calm of a studio retained a power and vitality as a result of the artists’ preliminary sketches. Among my favorites was this powerful drawing in charcoal by Harry Townsend.

The talented William Aylward specialized in nautical illustrations for the Post but proved with his work for the AEF that he was an artist of great range and depth.

With World War I, the battle became more accessible to the public through mass communication, so images took on a different role. It is therefore not surprising that war art also changed. Before the artist soldiers of the AEF, official war art depicted war as heroic and romanticized battles. Even the great artist Goya, who privately lamented The Disasters of War in his unpublished series of etchings, continued to paint flattering portraits of pompous generals and aristocrats as brave commanders. But there is nothing false or regal or flattering about the pictures at the Smithsonian exhibition. They are as tough and practical as the Yanks who created them.

The exhibition at the Air and Space Museum has been well received by visitors. Says curator Jakab: “The idea that World War I, an event affecting millions, was fought by individuals, each with their own story, has relevance for today’s conflicts. Unless you have a family member or close friend in the service, it’s easy to think of one soldier as being pretty much like the next. Military families who come through the exhibition recognize and appreciate what this art reveals about the lives of individual soldiers in World War I, and the lesson it provides for our own time.”

The exhibition will be on display through November 11, 2018. For those unable to make the trip to Washington, many of the works, along with the background of the exhibition, can be found on the website for the National Air and Space Museum.