Could Charm Schools Make a Comeback?

It’s unlikely that when future generations look back on this era, the word “charm” will pop into their heads.

In a time of trolling, bullying, flame wars, hate speech, and armed protests, such a concept seems quaint and useless. But charm is still with us, and organizations from The Etiquette School of New York to MIT are now offering instruction in attaining it.

At its least, charm is the ability to put people at their ease. In larger amounts, it delights people and arouses their admiration.

It is the culmination of good manners, but it is never an obvious display of etiquette. Said actress Sarah Bernhardt charm is “made of everything and nothing.” Charm usually catches people unaware; they find themselves captivated by and agreeing with the charmer. As Albert Camus described it, charm is “a way of getting the answer yes without having asked any clear question.”

Today’s charm instructors show the proper conversation, table manners, posture, and wardrobe to make the best impression. And there’s a growing market for it. Until the pandemic, Myka Meier had been teaching social, business, and dining etiquette at New York’s Plaza Hotel. She was mentored by a former member of the Royal Household in Britain and received further training at Switzerland’s last remaining finishing school. Earlier this year, she was addressing sold-out classes and her book, Modern Etiquette Made Easy, sold out on its first day.

Meier maintains that etiquette is not an antiquated concept. In her book, she writes, “With examples such as new forms of electronic communication, gender equality, and international travel, we have had to rewrite the rules of etiquette in many instances….Society is evolving and changing so rapidly, we must change with it.”

Charm instructors have even entered the workplace, though they call what they teach “soft skills.” According to a survey by Inc., 44 percent of top U.S. executives say these skills are their chief consideration in considering job applicants.

The demand for instruction in etiquette and charm in this country may be partly due to their scarcity. Historically, most Americans have been ambivalent about the importance of behaving themselves. In the republic’s early days, a small number of affluent Americans enjoyed refined living in America’s larger cities. But they often viewed the common people with scorn.

John Adams, attending a continental congress in New York complained that he hadn’t met a single well-bred man in the city. Young George Washington, surveying the unsettled lands of Virginia, described the frontiersmen as “a parcel of barbarians.”

There was little time and less opportunity on the frontier to acquire social polish. Europeans who toured America in the 1800s, says social historian Gerald Carson, were highly critical of “the slovenly dress and poor posture of Americans, their wolfish eating habits, the incessant chewing and spitting, the heavy drinking and generally unbuttoned behavior in steamboat, hotel, and stagecoach.” Many Americans, he adds in his book The Polite Americans, believed that rough manners were a virtue, not a fault.

But by the 1840s, many parts of the country had become settled. Americans who formerly struggled to find food and protect their families could now aspire to prosperity and gentility. Women, in particular, saw a mastery of etiquette as a means of being accepted by people of taste, education, and wealth.

Manners were a source of great interest for Americans, as reflected in the number of books that instructed “genteel” young ladies in the best customs. Titles like The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness by Florence Hartley, and Robert De Valcourt’s Illustrated Book of Manners shaped the behavior of Americans at home and among others.

In the years following the Civil War, the Post ran a regular column of answers to readers’ etiquette questions. From the August 29, 1874, issue, we learn:

- The third finger of the right hand is the proper one for the engagement ring, but by some it is worn upon the forefinger of the left hand

- At the dinner table gentlemen will sit next to the lady whom they have escorted thither, taking care to place themselves on her right hand

- It is not necessary in every case that the lady should rise on being introduced to a gentleman, but it certainly would not look well when she herself is introducing two persons for her to remain seated

In coming decades, several women — Caroline Astor, Emily Post, and Amy Vanderbilt — became the authorities on etiquette. But probably none of them popularized grace, manners, and charm better than Jacqueline Kennedy. Presidential advisor Clark Clifford wrote to her, “Once in a great while, an individual will capture the imagination of people all over the world. You have done this; and… through your graciousness and tact, you have transformed this rare accomplishment into an incredibly important asset to this nation.”

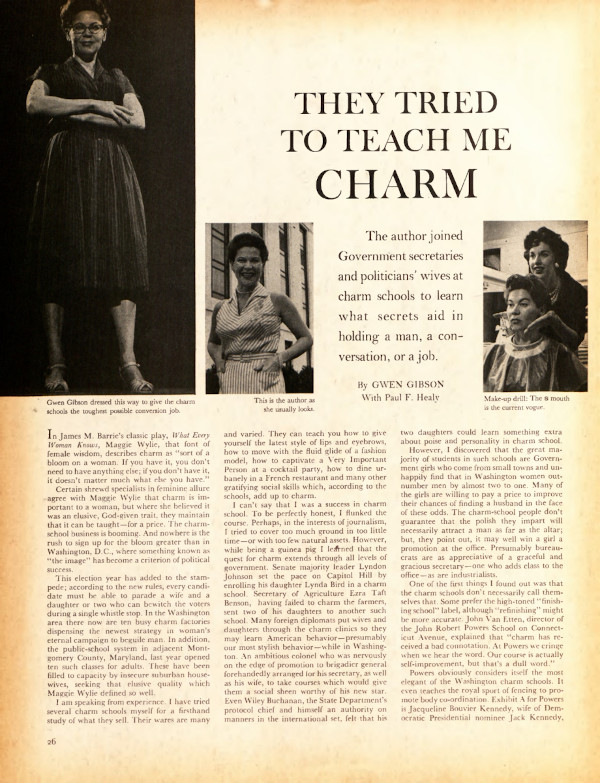

When she and President John Kennedy entered the White House in 1960, their image of cultured gentility became fashionable in the capital. In an August 6, 1960, article in the Post titled “They Tried to Teach Me Charm,” Gwen Gibson reported, “the quest for charm extends through all levels of government.”

In it she described her experiences in several of the new D.C. schools that sprang up to supply the needed instruction.

The director of the Patricia Stevens school told her charm was “an inner beauty that makes a person attractive,” although much of the class focused on her exterior. Gibson also wrote about the John Robert Powers School on Connecticut Avenue where “Mrs. Kennedy was polished to a high gloss in her premarital days.”

The pursuit of charm had long been the concern of women wishing to exude a certain savoir faire. But now, with culture and refinement so widely aspired to, charm could also be a reflection of their husbands or bosses. “The secretary who delights the eye, enchants the ear and lulls the nerves has become an important status symbol for her employer,” wrote Gibson.

They also studied charm, she said, to get a husband in a city where women outnumbered men 2 to 1.

Patricia Stevens’ students were taught “diplomatic phrases” to get men to talk. “One such line, guaranteed to perk up a frustrated civil servant, is ‘My, that’s an interesting point of view! I never thought of it that way!’” She also had warnings for smart women:

Not long ago the Stevens school analyzed a horsy female scientist, a Ph.D. who had been scaring men away with her overpowering intelligence. At Stevens she learned how to talk demurely, make herself up seductively, and wear something more feminine than tweeds….

High priestess of charm and culture in Washington is Mrs. Helene Williams, whose thirteen-year-old charm school is the oldest and most genteel in the capital. [She declares] no woman is dressed without hat, gloves, girdle and a smile.

Americans’ ideas of good manners have changed greatly since the Kennedy years. The baby boom generation seemed to bring an era informality in behavior and dress, and a generally broad acceptance of others’ lifestyles. But in an atmosphere of what would otherwise be a laudable tolerance, bad manners — rudeness even — has flourished. As author and coach Steven Handel has written, “Never before in our history has it been easier to treat people like crap then get away with it.”

Recently Parent.com made the case for reviving charm schools for the next generation, arguing that manners make the cold, hard truth bearable, writing, “Manners are meant to free us to be honest and direct while still signaling respect and consideration for another person’s feelings.”

Charm could be more valuable than simply knowing which fork to use for your fish course. It could help us to reduce the heated friction in our society. As Myka Meier says, behind all the details and customs of charm is a simple intent: to show respect, consideration, and kindness.

Featured image: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)