Con Watch: Watch Out for New Medicare Card Scams

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

Medicare has used Social Security numbers as Medicare ID numbers since its inception in 1965, a practice that has put recipients at increased risk of identity theft. And while federal law has prohibited using Social Security numbers as driver’s license numbers since 2005, Medicare resisted this change for many years.

In 2015, Congress finally enacted a law requiring Medicare to start using randomly generated numbers and letters for Medicare identification. This April, Medicare began sending the new cards by regular mail to all 60 million Americans enrolled in Medicare. The process, however, will not be swift. To get a little more information about your own card, you can register online to receive an email alert when your new Medicare card is in the mail.

Between April 2018 and December 31, 2019, Medicare recipients can use either their Social Security number or their new, more secure Medicare ID number. Starting in 2020, only the new Medicare ID numbers will be used.

Many people are confused about the switchover to the new cards, however, and scammers are taking advantage of the confusion. Pretending to be Medicare employees, the scammers call Medicare recipients and tell them they need to register over the phone to get their new card or risk losing benefits. They then ask for victims’ present Medicare ID number — their Social Security number — and use that information to steal their identity.

In another variation of the scam, victims are told they need to pay for the new card with a credit card or electronic bank payment. Remember: There is no charge for the new Medicare card.

If you are a Medicare recipient, you will eventually get your new card in the mail. You don’t need to do or pay anything to get your new card. If you need to update your mailing address, go online to My Social Security Account, a service of the Social Security Administration that allows you to set up a personal online account. Not only can you update your personal information, but you can also view your earnings history and estimates of benefits, manage your benefits, and set up or change direct electronic deposits.

This is a tremendously convenient service, but it also provides a great opportunity for scammers to set up My Social Security Accounts for people who have not already done so themselves and then to direct benefit checks to their own bank accounts. Even though the Social Security Administration, as part of the process for opening a My Social Security Account, requires verification of personal information by asking questions only the Social Security recipient should know, too often this information is available to a determined identity thief.

In order to improve the security of the accounts, the SSA now requires people to use dual-factor authentication to access their accounts. The authentication is a one-time code sent to either the user’s email or cellphone. But still, using an email address for dual-factor authentication may prove problematic because it is not particularly difficult for a sophisticated hacker to gain access to someone’s email account.

Just as the best defense against income tax identity theft is to file your income tax return before an identity thief does so in your name, so the best defense against the fraudulent use of your Social Security Account is for you to set one up first and protect its safety with a strong username and password. For information about signing up for a My Social Security Account, go to https://ssa.gov/myaccount/.

As a general rule, never provide your Social Security number, credit card number, or any other personal information to anyone who calls you on the phone; you can never be sure they are legitimate. Even if your caller ID indicates the call is from Medicare, the IRS, or some other legitimate organization, your caller ID can be tricked through a technique called “spoofing.” Medicare will not call you and ask for personal information. If you get a call that appears legitimate, but they’re asking for personal information, merely hang up and call the company or agency at a number that you independently know is legitimate.

If you have a question about your new Medicare card, you can call Medicare at 1-800-633-4227.

On the Side of Social Security

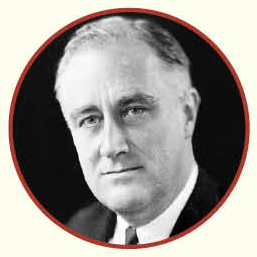

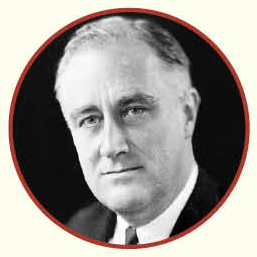

Eighty-two years ago, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act, a part of the Second New Deal that provided the foundation of government assistance in the country.

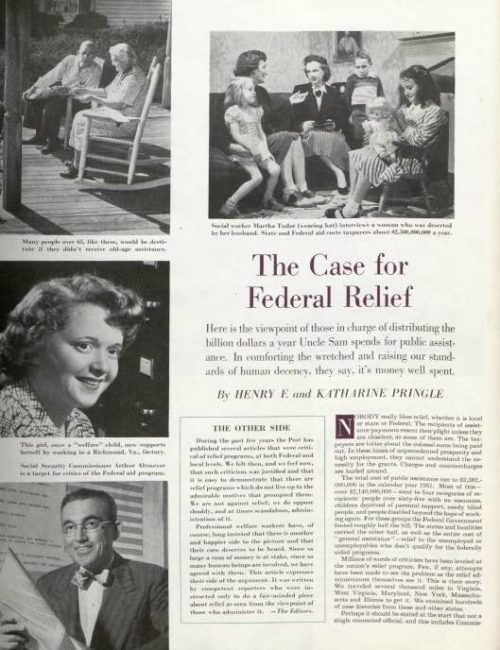

Although the Post was often critical of federal and local relief programs following Roosevelt’s New Deal, Henry F. and Katharine Pringle’s “The Case for Federal Relief” in 1952 looked at the beneficiaries of welfare and argued the necessity of programs that give security to the unemployed, elderly, abandoned, and disabled. The authors asserted, “Public assistance does not make bums out of people, if it is accompanied by good social work. The right kind of aid, in money, for minimum security plus guidance to get the recipient back on his feet, if that is possible, is the answer.”

In 1952, the public wondered whether “hillbilly” children ought to receive funds for shoes — since they weren’t accustomed to wearing them — or whether releasing the names of people receiving public assistance might deter greedy deceivers out of embarrassment. Although most people tend to agree on a sort of social safety net, the implementation of such is rarely unanimous.

A Year in Review: The Top 10 Stories of 2012

It’s been a great year for the Post, editorially speaking. We’ve covered a broad range of issues, from hot-button political topics like the wealth gap and social security to unique finds in our archives on mysterious crimes, the Titanic, and Rockwell paintings.

Amidst the trove of content we’ve provided our readers in the last 12 months, 10 stories had more traffic on our website and social media than all the rest. Here are the Post‘s top stories of 2012.

Statin drugs benefit some people immensely but are taken by millions more. If you’re at low risk for heart disease, taking drugs to lower your cholesterol may be doing you no good. Is it time we took a second look at statins?

Sharon Begley examines the pros and cons of the statin pill push, and finds that many doctors are staunchly against their widespread use.

Read more »

Despite a half-century of inquiry, the circumstances surrounding the death of an 8-year-old boy are still a mystery. What makes this case even more bizarre is that this boy, by all accounts, never existed. To this day his name, birthplace, and even his lineage are unknown.

Read more »

Thinking of taking the plunge? That’s exactly why director Steven Spielberg keeps this Rockwell painting in his office.

Historian and archivist Diana Denny divulges interesting facts about the models, the climate of the era, and Rockwell himself.

Read more »

This 1950 article claims that, in the event of an atomic bomb, “there are protective measures you can take—and proof that the blast is not always so fatal and frightful as you think.”

Read more »

As consumers increasingly demand organic produce, and as massive industrial farms rise to meet their needs, will it spell the end of the family-run, lovingly tended, earth-friendly farm?

Barry Yeoman analyzes the challenges and pitfalls grocers and small organic farms alike face in the wake of the growing demand for healthier foods.

Read more »

In honor of Memorial Day, we gathered some of Norman Rockwell’s most iconic art from both world wars.

Read more »

One hundred years after the Titanic sank, we explore the Post‘s 1912 editorial on the great tragedy. Were the British and American governments to blame for the 1,500 deaths? Our coverage explored the oversights, shortcomings, and outrage in the wake of the ocean liner’s horrific end.

Read more »

You’ve heard the rumors. Here are the facts. The Post examines the timeline of social security from its advent, parsing why it was started, what it aimed to do, how it helped Americans, and why there’s such a fuss about it in the current political climate.

Read more »

The country is polarized and embattled to the point of dysfunction. What will it take to bring us back together?

A self-described “one-time liberal atheist,” Jonathan Haidt discusses the differences between conservative and liberal worldviews, how he came to understand the other side, and asks whether or not this country can find a tolerant middle ground.

Read more »

Betsa Marsh took Post readers to the somewhat forgotten land of stately, grand hotels, where unlike today’s varieties, the opulence comes from the resort’s history and refined elegance, not its glitz and glamour. To stay at any of these lodgings is to venture back to another, more genteel time.

Read more »

Social Security

In the spring of 1935, at the depths of the Great Depression, Congress voted by a landslide to create Social Security—372 to 33 in the House and 77 to six in the Senate. Almost nobody was against it. In the years since, it has grown to be the biggest government program in history, anywhere ever, and arguably one of the most successful. It has lifted tens of millions of Americans out of poverty. Today it provides 56 million people a guaranteed paycheck, and nearly two-thirds of retirees count on it for more than half of their income. Yet many now see it as a huge failure. Among the 2012 presidential candidates, Rick Perry has called it a “Ponzi scheme” and a “monstrous lie,” and Mitt Romney has written that “to put it in a nutshell, the American people have been defrauded.” We are told it is going bankrupt. What happened? Where did Social Security come from? And is it really in such grave danger?

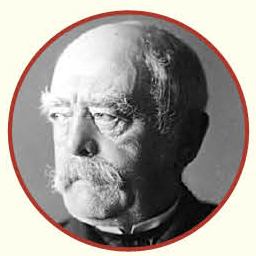

The story begins more than a century ago in Imperial Germany. In 1889 Chancellor Otto von Bismarck got a law passed setting up an old-age insurance program that required German workers to contribute a portion of their wages to a fund that would pay them in their retirement. Why? In a time of frightening worker unrest and socialist ferment, Bismarck bluntly admitted that he wanted “to bribe the working classes … to regard the State as a social institution … interested in their welfare.” In other words, he feared he had to start doing more for the workers or they might rise up against him.

Before long other European nations followed. The U.S., with its powerful spirit of self-reliance and independence, did not. Yet old age was getting harder for Americans. By the end of the 19th century the nation had gone from mainly agricultural to industrial, from rural to urban, and from extended families in which generations stayed together to what we now call the nuclear family, of parents and children alone. Americans who worked in factories or offices could easily find themselves out of a job in economic hard times, and when they retired they couldn’t fall back on their families as their parents had. Also, people were living longer. That all added up to more and more people facing long old ages without any resources.

A timeline of Social Security

Click on the arrows or dates to scroll through key moments in this interactive timeline.

- 1889

- 1933

- 1934

- 1934

- 1935

- 1940

- 1941

- 1944

- 1950

- 1956

- 1961

- 1972

- 1977

- 1983

- 1993

- 2000

- 2005

- 2008

- 2010

- 2011

- 2011

- 2011

European inspiration

German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck passes an old-age insurance program that becomes a model for Britain and other European nations.

An early American plan

Retired doctor Francis E. Townsend devises a program—funded by a two percent national sales tax—that would pay every American over 60 a pension of $200 a month that had to be spent within 30 days.

Protection for all

Louisiana Governor Huey P. Long launches the Share Our Wealth Society, which calls on the government to guarantee every family an annual income of at least $2,000.

Talks grow serious

Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins heads a committee that recommends a federal social insurance plan, which includes unemployment insurance and “old-age” security.

The beginning

Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the Social Security Act on August 14. Payroll taxes are first collected in 1937.

MONTHLY PAYMENTS start

On January 31, Ida May Fuller becomes the first to receive a monthly check. The amount is $22.54.

The guarantee

President Roosevelt is quoted as saying: “We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my Social Security program.”

The program grows

Mary Thompson, a widow, is the one millionth Social Security recipient.

Inflation, duly noted

Social Security adds a cost of living adjustment.

Help for the disabled

Social Security is amended to provide monthly benefits to disabled workers ages 50 to 64 and for disabled adult children.

An early retirement option

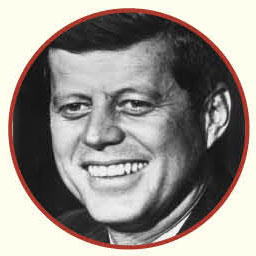

President Kennedy signs an amendment permitting men to retire at 62 with a reduced benefit. (Women had been given this right in 1956.)

A better inflation plan

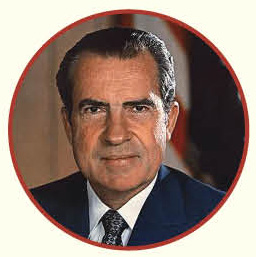

President Nixon signs an amendment to make cost of living adjustments automatic.

First fears of insolvency

Legislation is enacted to raise taxes and scale back benefits.

Money worries continue

President Reagan signs a law taxing benefits. The retirement age is raised from 65 to 67, but not until 2000.

Still more concerns

The taxable portion of benefits is raised from 50 percent to 85 percent.

Staying on the job

President Clinton signs a bill eliminating the Retirement Earnings Test (RET), allowing seniors who continue working to receive full benefits.

The privatization effort

After winning re-election, President Bush uses political capital to push for partial privatization—a program in which individuals would manage their own accounts. In the face of resistance from seniors and their advocacy groups, the plan slowly dies.

Generation Shift

Kathleen Casey-Kirschling, generally recognized as the first-born member of the baby boom generation, receives her first Social Security check.

A new insolvency threat

The U.S. Deficit Commission, set up by President Obama, recommends raising the retirement age to 68 and reducing the annual cost of living increases. The plan is not adopted.

The Challenge

“There are one of two ways you can make Social Security work forever. One is to raise the retirement age by a year or two. The other is having slower growth in inflating the benefits of higher-income of Social Security recipients.” —Mitt Romney

An outright attack

Republican presidential primary candidate Rick Perry calls Social Security a “Ponzi scheme.”

Drawing a line in the sand

“We should … strengthen Social Security for future generations. And we must do it without putting at risk current retirees, the most vulnerable, or people with disabilities; without slashing benefits for future generations; and without subjecting Americans’ guaranteed retirement income to the whims of the stock market.” —President Obama, State of the Union

Click Arrow For Previous Event

Click Arrow For Next Event

There were modest pensions for veterans and a few company pension plans, especially among railroads. After the Stock Market Crash of 1929 a few states tried to set up old-age pension systems, but didn’t have the power to effectively implement them. Most older Americans had nothing to fall back on. By 1934, it is estimated, more than half of the elderly in the U.S. were unable to support themselves.

Popular movements arose to challenge this dire situation and agitate for impossible solutions. Huey P. Long, then governor of Louisiana, started the Share Our Wealth Society, which called on the government to guarantee every family in the nation an income of at least $2,000 a year (about $33,000 today), plus a pension for everyone over 60 and confiscation of every personal fortune above $8 million. By 1935 Share Our Wealth had 7.7 million members. Francis E. Townsend, a broke 66-year-old retired doctor, launched a proposal in 1933 to pay every American over 60 $200 a month ($2,400 today) on the condition they spend the money within a month. The payments would be funded by a two percent national sales tax. He soon had millions of followers who organized Townsend Clubs across the country to promote his plan.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt said at one point, “The Congress can’t stand the pressure of the Townsend Plan unless we have a real old-age insurance system, nor can I face the country.” So, on June 8, 1934, he sent Congress a message urging it to enact “social insurance … to provide security against several of the great disturbing factors in life—especially those which relate to unemployment and old age.” He added that “lessons of experience are available from states, from industries, and from many nations of the civilized world.” He set up a committee of five cabinet-level officials headed by Labor Secretary Frances Perkins to come up with a plan.

The committee soon had a large staff and an array of subcommittees. The five officials divided their job into three parts, with one big group tackling unemployment insurance, one big group working on health insurance, and a much smaller group focusing on old-age security. The unemployment team bogged down in disputes, and the health care reformers were kept from doing much by opposition from the American Medical Association, which didn’t want doctors restrained by national regulation. The old-age group, however, came together on a plan where workers and their employers would each contribute, paycheck by paycheck, to a fund that would provide the workers a pension after they retired. It was a relatively moderate, conservative answer to the radical ideas of people like Long and Townsend.

At first the proposed Social Security law was attacked by liberals as doing too little and by conservatives as approaching socialism; but opposition faded, and President Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act of 1935 on August 14 of that year. The law included unemployment insurance, aid to dependent children, and other elements, but its biggest feature was the old-age part we now think of as Social Security. Taxes for it were first collected in 1937, and for three years the trust fund was built up before the first monthly Social Security check was written in 1940, giving Ida May Fuller, a retired legal secretary in Ludlow, Vermont, $22.54.

The idea was not to provide a pension where people would always get back the amount they put in; rather it was to collect a pool of insurance money from people and return it to them if and when they needed it. Thus what you receive depends on when you stop working, and a disabled worker can start collecting early and end up getting more than that worker paid in. Originally the law required you not to work at all after 65 to get Social Security no matter how much you had paid in. This requirement was intended to remove older people from the labor pool, creating more jobs for the young. The law also excluded farm and transient workers, domestic servants, and anyone working for someone with fewer than 10 employees. Those people may have needed Social Security the most, but legislators believed the tax would be too hard to collect from them.

The system has been modified and expanded many times since its creation. In 1940 benefits were added for a survivor of a retiree who died. In 1950 cost of living raises were introduced. Disability coverage was added in 1954. Also, Medicare and Medicaid, begun in the 1960s, are both officially part of the Social Security System. In the 1970s fixes started being made to keep the system from losing money; in 1977 the tax rate was slightly increased and benefits were slightly reduced, and in 1983 the retirement age was raised (to eventually reach 67 for full benefits) while the payout for early retirees and people still working was reduced.

Because the nation is going through an enormous demographic change with aging baby boomers, none of those adjustments has made the system permanently sound. There are now more Americans over 65 than ever before to take money out of the system and not enough younger workers paying in to keep up. Social Security’s financing is in need of repair. Nonetheless, the system is hardly on the brink of collapse, as some claim.

Around 56 million Americans, a sixth of the population, received Social Security benefits in 2011. The system is paying them a total of $727 billion. After years of taking in more than it paid out and building up a surplus, the system has just begun to dip into that surplus—the “trust fund” of government bonds, now at a peak of $2.6 trillion. No one can say exactly how fast the trust fund will diminish, but the Social Security Administration and the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) both estimate that if nothing is done it will last until around 2036. But even in that extreme case, Social Security will be able to pay out as much as it takes in. It just won’t be able to pay recipients 100 percent of what they get now; instead, they’ll get something like 76 percent.

How can the loss of money be stopped? There are four possible ways: raise the retirement age; reduce benefits or cost of living increases; raise the top income level for paying Social Security taxes; or raise the Social Security tax rate. If the tax rate were raised from its present 12.4 percent, half paid by employees and half by employers, to 14 percent, that would do it, according to the CBO. More likely is a mix of a smaller tax rise, a modest increase in the retirement age, and a rise in the cap on taxed salary.

In other words, Social Security has very real long-term funding problems, but it is not in a crisis that can’t be fixed. And as for those who say that its trust fund doesn’t really even exist because the government has spent all the money in it, in a sense that’s true—but it’s not a very meaningful sense. The trust fund’s money is all in government bonds, which pay an average of 2.76 percent. Any bond is, in effect, a loan of money to the bond’s issuer and only has value if the bond issuer can repay the loan. The bonds that compose the Social Security trust fund are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S., and it is almost universally agreed that the U.S. government is more dependable than any other issuer of bonds—or any other investment—on Earth. So the Social Security trust fund may not be 100 percent safe, but any other conceivable investment is probably less safe. That’s one reason why attempts to “privatize” Social Security—replacing the trust fund with individuals’ investments in stocks and other securities, such as President George W. Bush proposed in 2005—haven’t gone very far. After the recent stock market crash, privatization appeals to fewer people than ever.

And here’s a glimmer of good news in that long, uncertain future: Eventually, the flood of baby boomers will end, and older people won’t so greatly outbalance younger ones as they do in this unique period of history. So even if the next generation can’t retire quite as comfortably as Americans could in the unprecedentedly prosperous years since World War II, maybe the generation after that will be more comfortable again—as long as we don’t give up on a Social Security system that has worked wonders for millions of Americans for most of a century. There’s a reason it has been “the third rail of American politics” ever since House speaker Tip O’Neill first called it that in the 1980s: Everyone worries about it, but virtually no one wants to lose it.

From Our Archives: Uncle Sam’s Big Pay-Off

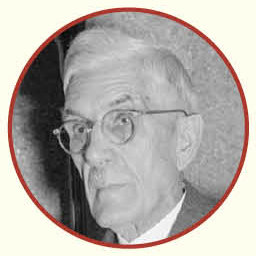

in the Jan/Feb issue of the Post, Frederick E. Allen gives us the facts about Social Security and explores its history. That history is well-known to Post readers. In 1955, Robert M. Yoder penned this article, which features a few of the thousands of letters that the Social Security Administration received on a daily basis.

UNCLE SAM’S BIG PAY-OFF

by Robert M. Yoder

Nov. 19, 1955

One reason the Social Security Administration gets mail by the truckload is that every day finds an average of 15,891 Americans in need of Social Security cards. About 8220 need replacements for cards destroyed by accident, lost or stolen. The other 7671 are beginning their working careers.

For the great majority of those setting out to earn a living a card and a number are indispensable. Sometimes you encounter a real hardship case Like that of J. Wilbur, born all but anonymous.

J. Wilbur’s mother wrote in about him:

Dear Sirs: In regard to J. Wilbur. Seventeen years ago on January 14 I birthed a son. He was a fine boy, weighed 12 lbs. at birth. There wasn’t any account number on him anywhere and the doctor attending did not stamp any number on him. He grew up quickly.

When he was old enough he went to school as all other boys do. Learned very fast as he was a bright tot. He has been working on his father and his grandfather’s farms. Wilbur is now in the 11th grade. Mr. Jones asked Wilbur recently would he help him in his meat market on Saturdays. He also told him to write and get him a Social Security card. The boy never before having worked anywhere but on the farm we never did number him nor anyone else number him either. Will you all please number him and send him a Social Security card?

The Social Security people made haste to number poor unnumbered Wilbur, because if you don’t have a number these days you are cooked, and no two ways about it. You would also feel a little left out. For outside of the weather, taxes and the two-sex system, few things concern so many Americans as does Social Security.

Babies by the thousands are supported by Social Security benefits, and the other day a man in Massachusetts asked for a card at the age of 102. Some 69,000,000 citizens contribute every payday or when they pay their income tax, and while only 78,000,000 accounts are active, Social Security actually has a whopping total of 115,000,000.

That many interested parties are bound to have a great miscellany of problems, claims and questions. So it is not surprising that mail trucks bring 300,000 to 400,000 letters a month to national headquarters of Old Age and Survivors’ Insurance activities, in Baltimore, with thousands more arriving at the six area and 532 district offices.

Most of the letters in this Mississippi of mail are routine business correspondence. But there are anxious letters and sad ones. And it lightens and brightens the job that there are also funny letters: From the man who wanted a new card rushed “because I need it to obscure my job with.” From the man whose card “was stolen or picked” in spite of the fact that he was “in a sobber state of condition.” From the woman who thinks Social Security can be turned on like electric service. “I would like to draw Social Security for the coming five months, taking effect the 10th of December,” she wrote briskly. “Due to circumstances beyond my control, I have become pregnant.”

There is a steady stream of letters asking the big social-insurance agency to locate someone. With nice economy of words, one letter painted the picture of a man who finally broke under a great common burden. Many will know how he felt. Said the letter:

“Dear sir: I have a cousin of mine who is missing for three years. He went away to pay his income tax and never showed up any more.”

The assumption that Social Security is on familiar terms with all its millions upon millions of clients brings in letters like the one from Millie. “Please get in touch with Dan, my husband,” she wrote, “and tell him to call or write home right away, the bathroom is out of order, water is leaking under the house. I don’t have money to fix it. Thinks.”

Social Security and the Railroad Retirement Act are correlated. It may be necessary to decide which fund pays a wage earner’s survivors. So a standard question is asked: did the wage earner ever work for a railroad? To many, the question seems odd. To one widow it seemed entirely natural. “My husband never worked for a railroad, ever,” she wrote. “You must be thinking of his brother, Willie.”

Social Security knows a Willie or two, she was right about that. In Smiths alone, they’ve got some 32,000 Wills, Willies, Williams or Bills. But Social Security doesn’t know all its clients personal-like, as you might say—not as well as the widow seemed to think.

Name changing produces a lot of mail, including this little lament: “Sir: I was living here under another name on account of a woman. She said to go under that name. Which she has gone and got me into a mess of trouble under that name. So please sign my card in my right and lawful name.”

“Dear sir,” one woman wrote impatiently. “As you was asking why wasn’t my name the same on Item 1 and 3. So as you may know. People are always getting married. Arn’t they? And that is exactly what I done.”

People sure always are, and it is tough to keep up with some of them. An impulsive Texas girl asked for a new card on February second because she had just married. She wrote next to ask for the old card back “as I am no longer married.” That was on February third.

Or they don’t quite get married, and it takes several letters to find out just what the deal is. When an insured wage earner died, in the Southwest, it appeared he had a common-law wife to whom benefits should be paid. But Rosa, the lady in the case, said the relationship was purely informal and for fun. “I was just room here,” Rosa wrote, “and he was my boy friend. Because I have a husband.”

A widow’s right to receive benefits sometimes is beclouded by a previous marriage. In Lucy’s case, Social Security needed assurance that Lucy’s first marriage, to Frank, had terminated in some definite way. Lucy wrote back that it was definite enough.

“You want to find out how my marriage to Frank ended. Well, sir, I DEVOURED him. Signed with my own hand, Lucy.”

Another widow, hoping for benefits as the survivor of Husband No. 2, needed evidence that her first husband was not an impediment. She wrote her mother in Mexico. Mamma replied with spirit.

“How thoughtless are the gentlemen,” she wrote. “You first husband is now dead and it is impossible to dig him out of the cemetery. I am very sorry. If he were alive I would have found him and would have sent you his head in a box.”

What mamma had against poor Juan, or Pedro, or whatever, she didn’t say. He may have been shiftless. Some men are. As this letter makes clear:

“Dear Social Security: My husband took sick January 20 and died Feb. 27. He hasn’t earned anything since.”

Sometimes a mix-up is Social Security’s fault. The administration got one card back with the complaint “You spelt my name rong.” But a little confusion is inevitable. A Mississippian with a card in one name began using another. Asked why, he explained that his mother had just remarried, at eighty-four. Her boy, aged sixty-five, had taken the name of his new papa.

On suitable proof of death, a lump-sum payment is made to defray funeral expenses. Often something less definite than a death certificate must be accepted, since not everyone dies in bed. Social Security was satisfied in Emil’s case. For about Emil’s passing, to a watery grave, a witness wrote this:

“The last I saw of Emil he was pulling on the whistle frantically to signal the other boats with one hand and holding the wench with the other.” They assume the writer meant “wrench” or “winch,” but in any case it seemed clear that Emil was gone.

Sam’s friends didn’t see him make his exit, but they were confident Sam was a goner. Said a letter about this:

“Dear sirs: Everybody here is sure that Sam is dead. We and the police looked everywhere for him. He was very regular and we could always count on where he was if he wasn’t home. At Johnny’s Stag Bar they said they knew he’d walk in the door at 5:30 on the dot every night. But he never came that night, so I know he must be dead.”

Jimmy’s wife said there was no doubt in her mind about Jimmy either. She knew him. He was dead, all right, or he’d come home for meals.

“Gentlemen: I know what’s in your mind. You think that James walked out on me. Well, he threatened to, often enough, but he never meant it. He liked his comfort too much and he couldn’t eat restaurant cooking. If he’s still alive, it would be a big surprise to me. It just wouldn’t be like him.”

Usually the lump-sum payment, running from $90 to $255, is to a close relative. Occasionally the expenses are borne by a seeming stranger. Then Social Security looks into the circumstances. “You were hardly more than a casual acquaintance,” one man was told. “Why did you pay this man’s funeral expenses?” His answer was simple, plain and without a trace of self-glorification.

“Well, sir, I had to,” he said. “He warn’t in no shape to do it.”

What with one thing and another, Social Security people are hard to surprise. Even so, one death notice hoisted their eyebrows, for it seemed to come directly from the late lamented. It was a letter apparently asking for the lump-sum payment, and it said:

“I, Enola, died Sept. 14. Please answer and let me know. Thanks.”

That line of Thomas Gray’s about “the short and simple annals of the poor” is much admired. Any Social Security correspondence reviewer would observe, however, that the poet didn’t know many poor people. Their affairs, financial and domestic, can be complex in the extreme. The same is true of men and women in middling circumstances. One of Social Security’s widows has married nine times since they began keeping track of her. Nine husbands, all different, wouldn’t present much of a problem, but she favors two men, marrying first one and then the other. And in interludes of singleness she prefers to revert to her original married name; though it has been explained to her that she can no longer claim widow’s benefits.

The “ordinary man” frequently turns out to be an extraordinary fellow indeed, battling extraordinary problems. The proprietor of a coal yard was reproached for not keeping up on the reports an employer must make. He replied that he was having woman trouble, at age seventy-two.

“I would have complied long ago if I could,” he wrote. “I have a wife seventy years old. My business doesn’t justify me having someone just to do my writing. I can’t keep a combination housekeeper and to do my work because my wife is so jealous. No one will stay long enough to learn the work. She makes them sleep in the hall or in the room with her, when we have plenty of vacant rooms. If you have any suggestions that will help, I’ll be glad to co-operate.”

Many a big-business executive might not be able to take the troubles which snap and yap at the little businessman. Sometimes they prove to be more than the little businessman can take. Reproved for not filing returns on time, one man—the names are fictitious—replied as follows:

“Sir: I had an accountant, a Mrs. Warren, that got pregnant. Everybody was so surprised, but she and her husband seemed to know all about it. One day she was working and the next day she was in the hospital and back and forth she went.

“She had various employers, and one, a Mr. Phillips, overdrank and dropped dead. This caused Mrs. Warren to miscarry her baby, and by the time I got my books out of this six months calamity I am surprised that any of it was reported correctly.

“I paid the accountant to do the work and she was supposed to do it right as well as the accountant who took over from her. I was very careful to get a man that time as I found out you can’t do anything with a pregnant bookkeeper. However, the man I got turned out to be a preacher on the side. I finally got so discouraged I sold the damned hotel.”

There are days when you can’t lay up a dime, whole years when working gets you nothing much but exercise. The self-employed sometimes find themselves—in the expressive phrase of one Social Security claimant—”suffering from inability.” A farmer reported that he raised a lot of hogs, sold them, and sat down to figure out his income, so he would know how much Social Security tax to pay. No matter how many times he figured it, he said, he came to the same conclusion—no loss, but not a nickel’s profit for all his labors with those hogs. “Anyway,” he reported philosophically, “I enjoyed their company.”

“Please use the back door,” a Social Security field worker was directed, “as the front steps don’t exist.” That is often the case with birth certificates, and establishing correct ages may be tough. If there is a family Bible, that may help. The Bibles often contain a wealth of information, crisply reported. In one, after a whole list of children born to one union, there was this terse notation: “Maw quit Paw—June, 1923.”

To one woman it was suggested that her husband might have documents bearing on her age. She replied in wrath. “I dare you to write me about him any more. Please remember that I did not live with that sorry man and do not class myself with that trash. These people may be your class, but not mine.”

Another didn’t remember the date of her birth, but did remember the gunfire which that event occasioned. “There was doubt,” she wrote, “as to my rightful father. I can faintly remember seeing five men shot over my birth or my existence when I was around five or six years old.”

Social Security workers are an enthusiastic lot, who regard the big insurance program as the happiest thing to happen to this country in many a year. Some of them have voluntarily postponed their vacations four and five years hand-running, to keep the work rolling; some field representatives put in a fourteen-hour day straightening out the affairs of men and women in remote communities. Effort like that is bound to generate friendship. Many a business house gets a good response when offering an informative booklet. But its customers probably don’t enclose a quarter for a free booklet, and write, as one man wrote to Social Security: “please take contense and go and git you a bottle of beer.”

The friendly feeling shows up in chatty letters full of neighborhood or personal news notes. Like this:

“Dear sir: They told me you want to get rid of a typewriting machine you all have. I would be tickled to own one. I would give you good money for it. It would be real nice to write a letter and not have to use a pensil, my pensil is always broke and the butcher knife is dull because the baby digs holes in the yard with it. I got the money left from the hawg I razed last yr. I had to use part of it when our cow got the black leg. It didn’t do no good. Old Pansy dyed enyway. Yr true fren—“

“I don’t know how you figured my check,” wrote a satisfied customer, “and I don’t care. But I think it was largely owing to the good job you did. If you ever want a murder done, let me know.” Another wrote: “Never was allowed a Social Security number before. I’ll be just as tickled with it as a pig with a tail on both ends.”

On the other hand, there is no telling what simple question will provoke a storm. Applying for an account number, one man failed to supply his father’s name. Asked for it, he wrote as follows:

“Stranger: You can get my father’s name from the county court house. I positively will not give it to you. To hell with any number or anything else as far as I care. It seems to me a lot of you people want to know too dam much that is none of your business.”

There is a steady demand for advice on problems of heart and home. One sixty- four-year-old woman would in a year begin drawing widow’s benefits. But she was engaged, she explained, to a man of sixty-five. She wondered: Would she be better off, benefit-wise, as a widow or a bride?

“As a wife,” she was told, “you will have to be married three years before you can draw benefits.”

She said promptly that she would call the engagement off. “It pays to go into these things,” she said. “Three years, is it? I just don’t think it’s worth it.”

But Social Security felt duty-bound to show her the whole picture. In the unhappy event that her new husband died after hardly more than a taste of wedded bliss, she could draw benefits after one year of marriage to him. That put a different complexion on things. Three years, no. One year, yes. “In that case,” she said briskly, “I’ll just go ahead with my plans to marry and thank you very much.”

Now and then a little confusion develops over mothers’ benefits. A young widow draws benefits of this nature, but they stop if she remarries. Even so, payments to small children go on. Little Howard’s mother got a mothers’ benefit check after she had remarried. She wasn’t entitled to it, and sent it back, announcing her decision:

“I have married, but Howard is still with me,” she wrote. “I am sending the check back and keeping Howard.”

There are letters written in black despair, from those trapped in an impoverished old age. But there are others from good jaunty souls meeting old age with fine serenity. Notifying Social Security that it was time to start sending those checks, one man wrote:

“Well, the wheels has rolled around to three score and ten. I understand I shall receive a donation from our good old U.S.A. I have the enclosed number and am self-employed. I have purchased me a rod and reel and a .22 to kill frogs for bait. I have retired.”

In only twenty years, Social Security has become “a basic resource . . . for most American families,” in the phrase of Commissioner Charles I. Schottland. It is “the cornerstone of the Government’s programs,” as President Eisenhower put it, “to promote the economic security of the individual.” And an old boy in Denver figured the program could increase its usefulness by doubling as a matrimonial bureau. After a Colorado disaster, it was announced that the women widowed by the blast would receive as much as $25,000, over the years. A sharp-eyed widower at once took pen in hand.

“I am at home after 4:30 every evening,” he wrote, “and would like to meet some of those nice women.”

A further testimonial comes from an oldster who said this mighty piece of social engineering had tided him over just fine until he found something which was more fun. Returning a pension check, he wrote:

“It is with great pleasure that I inform you that I have returned from the never-never land of retirement to the land of the living, the ranks of the employed. At 70 years of age, a bachelor, with a book-keeper’s career behind me, I am starting a new career as a salesman of household products. I am going out into the wide world and meeting the fairer sex on equal terms. I find ladies in almost every kitchen who look with favor on me, who take pleasure in inspecting my wares and chatting over a cup of coffee.”

Ladies whose husbands, he added smugly, “apparently do not have the gift of conversation,” though all right at earning money, with which to buy household products.

A great many of the letter writers want a general description of the whole program. In this thirst for knowledge, this praise-worthy interest in public affairs, they may even be impatient. Like this:

“Dear sir: It seems like we just get our card game going when someone starts in on politics or something, lately its been income tax and Social Security. What conditions must excist before Social Security can be collected and how is it firgured? Please settle our argument so we can go on with our card game.”

To read the full original article, see below.

[embedpdf width=”700px” height=”900px”]http://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/wp-content/uploads/satevepost/uncle_sams_big_pay_off_orginal.pdf[/embedpdf]