North Country Girl: Chapter 40 — Return to Mexico

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

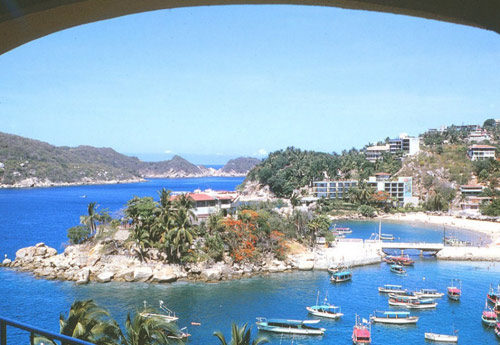

Mindy and I had our last day by the lovely El Presidente pool, drank our last coco loco cocktails, and our Spring Break was over. It was our final night in Acapulco. Part of me just wanted to spend it in our hotel room, reading one of the ponderous textbooks that I had stupidly brought along till I fell asleep in a bed by myself. I had been given a week straight out of a cheap romance novel, a Spring Break that would have taken the gold in the Spring Break Olympics; I could rest on my laurels.

But it was Mindy’s last night too, and she had been such a good sport and good friend. If I had to go down in flames, getting dumped in public by my Acapulco boyfriend, at least we could eat spareribs and drink margaritas at Carlos’N Charlie’s one last time. I happily agreed to skip Fito’s lounge act. I don’t know if even the most devoted groupie could have endured hearing him sing “Little Red Riding Hood” one more time. And one way or the other, our fling, our romance, was over.

Mindy and I put on our cutest outfits, the ones we had been saving for our last night, and headed out. Thanks to our day on Baldy’s swimming platform, I had achieved as perfect a tan as a Minnesota girl could. My skin had browned to the exact shade of a Parker House roll and my hair had sun-kissed highlights no beauty shop or bottle of Sun-In could replicate.

No longer rubes, Mindy and I presented ourselves at the door of Carlos’N Charlie’s and were whisked inside, ignoring the glowers from the tourists waiting in line. The bartenders and waiters smiled and waved as Mindy and I were led to a balcony table that had a full view of the dining room and bar, and more importantly, where everyone in the restaurant could see us. I assumed that our VIP treatment meant that Fito was not canoodling with another blonde at the bar, but I carefully scanned the room anyway.

Fito was not there, but looking deeply and directly at me was another gorgeous, perfectly tanned Latin male in a blindingly white shirt, a man who made Fito look like a mutt. Years later, when I first saw Andy Garcia in a movie, I was convinced for a moment that he was the guy from the bar, the guy who had me in his sights and was smiling a very sexy half smile.

The next second, he was at our table. “Hello gorgeous ladies. May I buy you a drink?” Once again, Mindy got thrown under the bus, as Javier, as he introduced himself, was flying solo and was there for the blonde. My prayers had been answered.

Javier had shiny black hair, combed straight back from a widow’s peak, that gave him a touch of the mysterious. He had those deep-set eyes I cannot resist, eyes that were hooded under thick brows and thicker lashes, and perfect white teeth that out-gleamed his shirt. And he had a certain something special about him that even Fito the Fabulous lacked; I later realized that Javier’s shimmering aura came from being the heir to a large Mexican fortune.

This will work, I was thinking, here’s my out. I can’t be dumped by Fito if I am with another guy.

“Where are you from?” I twinkled. Javier lived in California and was a ski instructor. People skied in California? I had never heard of Mammoth. In Minnesota, a fancy ski area was one with a chairlift, and the only instructors were ski team girls teaching little kids the snowplow. I tried to make skiing small talk while imagining how Javier would look on a ski slope, but the idea that kept popping up in my mind was how you can make candy by dribbling hot maple syrup on freshly fallen snow.

Javier was speaking lower and lower, his face getting closer and closer to mine. Mindy spotted Jorge at the bar and grabbed her drink to go say goodbye. Javier exhaled in my ear, “Where are you going after dinner?”

I told him I didn’t know and confessed that it was my last night in Acapulco, which spurred Javier to move in for the kill. I let him kiss me, slitted my eyes, and watched Fito walk into the restaurant. As Javier pressed me back against the booth, Fito looked my way and buckled in astonishment. He turned and headed towards Jorge and Mindy at the bar.

I had won at this game, even though I would have been hard pressed to explain the rules, and I wasn’t sure what the prize was, outside of not ending up like Miss Sweden, brushed away like a piece of lint.

Mindy spent her last night of Spring Break at Armando’s, listening to Jorge make his final pitch to get her to sleep with him and watching Fito sulk. I spent my last night with the skiing Andy Garcia. We ended up in his room at—where else—the El Presidente hotel.

A few minutes after we had slipped into his bed, with very unfortunate timing there was a pounding on the door, a pounding that did not cease despite Javier yelling “Vete!” followed by what had to have been some extreme Spanish curse words. Then we heard a key turn in the lock and the door opened. It was the El Presidente’s house detective, who accused me of being a hooker and threatened to have Javier kicked out if I didn’t leave immediately. The detective stepped out of the room and lit a cigarette, my cue for how long I had to get out of there. I dressed and kissed Javier goodbye forever.

“Don’t you come back,” hissed the house dick and grabbed my elbow in a way that showed me he meant business and left a bruise for a week. I was escorted out of the El Presidente to do the midnight walk of shame back to my own crap hotel where I packed my pink Samsonite, making sure to shake all the roaches out of my bikinis and gauzy dresses and miniskirts. The next morning Mindy and I were on a plane home to Minneapolis.

After a week of sunshine, poolside lounging, and swanky, glittering discos, coming back to snowy, sleety Minneapolis in March was like waking from a wonderful dream. No place like home my foot. If I were Dorothy I would have been banging my head against the wall trying to get back to the Emerald City of Oz.

Always the good little hamster, I climbed back on my treadmill, going to school, going to my waitressing job. The grey days melded into each other. I dutifully trudged through the chest-high snowdrifts to my spring semester classes, where I tried to concentrate, to banish the Technicolor memories of—could it only have been the week before?

After classes, I waited in the cold for a bus to take me to work, the pale sun setting behind the Mississippi River, shivering and sniffling and hoping I wouldn’t be too late. I leapt off the bus at my stop, ran down the steep, slippery, snow-packed hill, and threw open the back door of Pracna that led to the staff room. Amid the fug of cigarette smoke and Jovan’s Musk, I stripped off my fifty layers of winter wear, put on my green apron and my most charming, obliging smile, and went out to greet my first table and run my feet off for the next six hours.

I was not alone in my unhappiness. Patti’s week in Florida with Eduardo’s family had not gone well: la familia was too busy fussing over their darling hijo to even pretend to notice the red-haired gringa he brought along. No one had said two words to Patti, not even Eduardo as his mother continuously spooned his favorite Cuban food into his mouth as if he were a very large toddler. When the maid showed Patti to the pool house, where she would be sleeping alone for the week, Eduardo just shrugged and went back to his pernil.

At work Patti slammed around the paper plates, cursed at the cooks, and chain smoked in the staff room. She radiated anger. She wasn’t speaking to Eduardo, waiting for him to apologize or even better, propose. Since Eduardo and his car were no longer around to ferry us home, Patti, Mindy and I shared cabs in uncomfortable silence after work. And without Eduardo’s warm, inviting, pot-filled apartment to go to, every night I ended up back in my own place, where the thermostat struggled to hit sixty degrees. My friendship with my roommate Liz had already turned frosty; I had been too caught up with work and my new friends. I was tired, lonely, and cold.

Just when the rest of the civilized world was welcoming the first robin and crocus, Minneapolis was hit with a furious blizzard and temperatures in the single digits. In those days in Minnesota, there were no weather-related closings. Even elementary schools sent out their snow-tired yellow buses to pick up frozen, ice-covered lumps waiting on corners. Crossing the campus to my eight o’clock class, I felt like Robert Scott at the South Pole. It seemed that no matter what direction I walked, I was heading into the wind, a wind that threw sharp-edged, blinding sleet into my eyes and the bridge of my nose, the only parts of my body that were exposed to the elements. The gales blasted snow down the tops of my boots, where it melted into ice water. By the time I got to Pracna, I had to take a few minutes to rub life back into my pink and numb feet before gingerly easing them into my work shoes—minutes that were clocked under the stink eye of my manager.

In the restaurant I was greeted by a shocking sight: the dining room held only a handful of couples, thawing out with bourbon or rye. When I went to the bar to fetch drinks, a row of empty bar stools stretched out before me. The hostess slumped over her stand, waiting for someone to show up. The jukebox blared out “Crocodile Rock” to an empty room.

That blizzard was the last straw for normally hardy, weather-resistant Minnesotans, people who enjoy tobogganing and skiing in white-out conditions, who sit for hours on frozen lakes ice fishing. But now everyone in Minneapolis looked out the window, checked the thermometer, said, “Hell with it. I’m done with winter,” and hunkered down in front of the TV.

For most of our shift, Mindy, Patti and I huddled around the end of the bar, eating maraschino cherries and beer nuts and not talking. The bartenders stopped cutting limes and started smoking. It was as if we had all gone into hibernation.

The blizzard did not let up. I was no longer coming home with my pockets full of dollar bills. I sat in class, my mind bouncing from grey worries about money and how late the bus to work would be, to glorious snapshot memories of Mexico, memories so sharp and clear that I could almost feel the warmth of the sun on my face, smell the Coppertone, hear the echoing throb of “Push Push in the Bush.” I snapped to only when the other students got up to leave and looked down at my notebook, as blank as when I opened it an hour before, the pencil resting forlornly across the page.

I had glimpsed what life outside Minnesota could be like and wanted more of that, away from this endless winter. That night I slipped under the eighty blankets piled on my bed, and right before I shivered myself to sleep, I remembered what the smitten Jorge had said to Mindy: that if she wanted to stay in Acapulco, he could get her a job.

I made one last freezing, sleeting walk across campus to the bursar’s office where I officially dropped out of college and got my full tuition of $222 back. I had more than enough money to fly to Acapulco. I quit my job at Pracna and said goodbye to Mindy and Patti. With so few customers, everyone could use extra shifts, so no one minded my leaving on short—actually no—notice. Mindy hugged me and wished me luck and didn’t act as if I had lost my mind. If anyone understood the scrambled desires running through my brain, she did.

Liz was not so understanding about me leaving, and with good reason. She now had to either pay all the rent herself or find a new roommate for one semester, a semester that had already started. I was a jerk to leave her like that. I was out of my mind, worn out by winter and work and bedazzled with visions of discos and hot sunshine and handsome Latin men. I packed my pink Samsonite and flew out of the snow and cold, headed south again.

North Country Girl: Chapter 39 — Life as a Mexican Groupie

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

As a horny, homely teenager I often daydreamed of being a rock groupie, pinballing between Roger Daltrey and Robert Plant, with a quick stop at Mick Jagger, dressed in cute hippie clothes, my eyeglasses magically vanishing from off my face at the same time I grew three inches in height and four in bust line.

But I had never come face-to-face (or face to any other body part) with a celebrity. Growing up in Duluth, Minnesota, our local VIPs included Mr. Toot, the host of afternoon cartoons; Dottie Becker, the bubble headed brunette with the rigid smile, the doyen of the one-to-three TV slot (the second Dottie’s unhinged grin appeared on our TV, my mother marched over to click it off, believing that Dottie had unfairly beaten her out in the audition); Ready Kilowatt, the electric company’s mascot; and Joe Huie, the eponym and ever-present owner of Duluth’s only 24-hour restaurant.

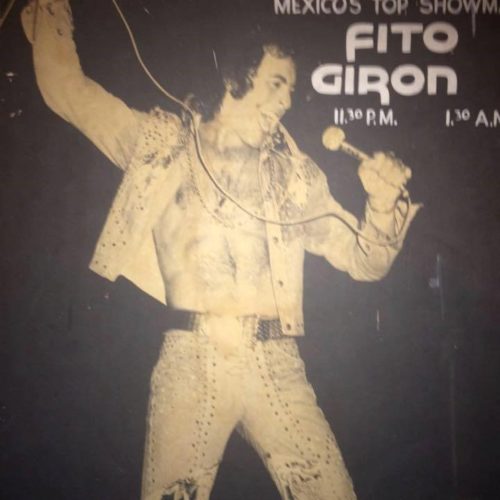

Now I was with a rock asteroid, the “International Singing Sensation” Fito Giron, who had plucked me from out of the flock of Spring Break coeds, locked eyes with me during his romantic rendition of “Wooly Bully,” and introduced me to disco dancing and then his bed. That night with Fito was the start of my marvelous, award-winning Spring Break in Acapulco, a fantasy “Where the Hombres Are.”

The next afternoon, I disentangled myself from the silk sheets, stumbled into the tropical sun, found a cab, and went to the Holiday in Hell Inn to collect my travel partner Mindy. Mindy and I headed back to the El Presidente pool, where we were greeted like visiting royalty by the staff. Fito and Jorge did not show up that day. In fact we never saw them by the pool again. Just as I started to panic—had I been dumped after a single night?—and steeled myself for a conversation with a beer-chugging Aggie, a waiter delivered a message with my coconut: Mindy and I were to meet Fito and Jorge for dinner at Carlos’N Charlie’s, the restaurant equivalent of Armando’s.

Carlos’N Charlie’s was what Pracna might have become if it had better food, real plates, and prettier customers who were not bundled up in turtlenecks and sweaters. The second story restaurant perched above the bustling main drag was bathed in flattering light, with more flattery coming from the handsome and obliging waiters and bartenders.

Carlos’N Charlie’s became our regular spot, whether Fito was there to pick up the check or not. Every night, the charming and smiling maître d’ whisked Mindy and me inside and led us to one of the coveted balcony tables overlooking the crowd milling about on the street, waiting and waiting to get in. If Fito did show up to dine with us, he always ordered oysters, which were served in a dozen different ways, from my favorite, Rockefeller, tucked under blankets of bread crumbs and béchamel and spinach, to the way Fito liked them, still quivering on the half shell.

These were my first raw oysters, as I had a serious grudge against them: on my hands, under the still visible white marks from flint knapping disasters, were faint scars from amateur oyster-shucking at my first restaurant job. Fito held the shell, rough on the bottom, pearly smooth on top, up to my lips like a raw, salty kiss, and gently slid the oyster into my mouth as if it were his tongue. Each oyster was followed by a real kiss and a silent promise to prove the purported potency of oysters later that night.

After dinner, we crossed the street to the El Presidente to watch Fito gyrate his hips, sweat, Wooly Bully, and thrill the females in the audience. I never tired of his cheesy, Latin Tom Jones act, I guess all groupies must enjoy seeing the same damn show over and over. Then it was into the Mercedes and off to Armando’s, for hours of vodka, champagne, and dancing as foreplay. During the day I tried to catch up on my sleep on a lounge chair by the El Presidente pool, relying on Mindy to chase away drunken college boys.

Guys kept trying to pick us up at the pool or Carlos’N Charlie’s, but I was with the handsomest man in Acapulco. I had no desire to hang out with a sun-burned economics major from Purdue or an aspiring journalist from Northwestern. I urged Mindy to get some Spring Break action herself; as sweet and accommodating as Jorge was, in the orbit of Fito’s brilliant sun he was a dull little moon and was not about to get lucky with Mindy. Mindy assured me again and again that she was having a great time at the El Presidente pool and cocktail lounge and at Armando’s. She was fine playing Ethel Mertz but she did not need a Fred around.

Towards the end of our Spring Break week, Mindy and I were on our usual pool side lounges, she sipping a cocktail and me trying to ignore the blaring music and glaring sun and catch a short nap, when a short, bald, whiskey-colored man in a black Speedo popped up like Rumpelstiltskin. We were bored of toying with the male Spring Breakers and I was running on too little sleep to shoo anyone away, so we ended up listening to this dark imp’s spiel.

Baldy was American, he was semi-amusing, and he said he was rich. Would we like to see his house, have a swim, maybe stay for dinner? Mindy and I had a quick whispered confab. We agreed that it would be fun to see something else in Acapulco besides the El Presidente and Armando’s, and if the old codger did turn out to be a creep the two of us could easily take him. And we wouldn’t have to hear “Hey, where do you go to school?¨ or “Didn’t I see you girls dancing at Le Dome (heavens no!) last night?” one more time that afternoon. Mindy and I were the Spring Break golden girls, nothing bad could happen to us. A visit to Baldy’s would be one more fabulous adventure.

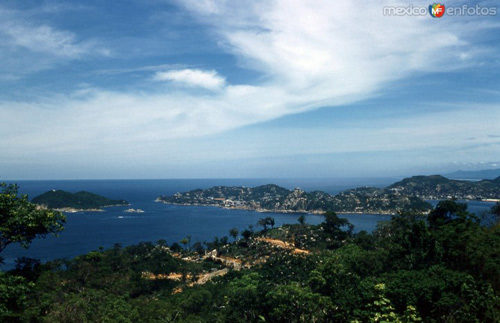

Baldy did have an incredible house, cantilevered over the ocean on the rocky cliffs at the far side of Acapulco, where you could safely swim in the ocean without worrying about garbage floating by or the sharks that followed the garbage. His house had a huge picture window angled so that all you could see was blue sea and sky. Despite the streaming sunlight outside, the inside of the house was dark and gloomy, with heavy mission furniture and ugly, shadowy, oversized paintings in gilded frames on every wall. Baldy had actual servants, which I thought existed only in books or royal palaces. One of them, a short silent woman, brought us chicken sandwiches and icy Coronas as we sat on the patio looking out to sea, before vanishing back into the dark interior.

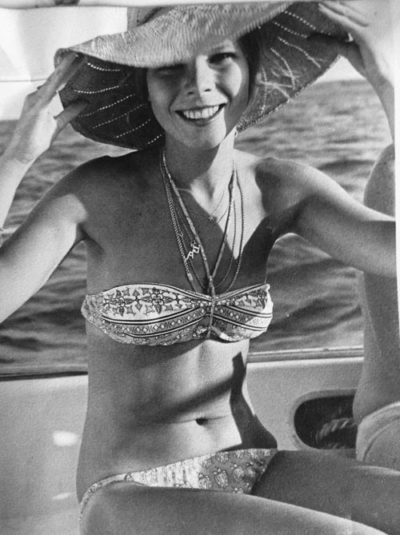

After lunch, Baldy, who had stayed in his black Speedo the whole time, encouraged Mindy and me to change into our bikinis and take a swim. There was no pool or sandy beach. Hammered into the rock cliff was a death-defying red metal ladder that descended thirty feet from the patio to a sea-level cement platform. The ladder looked almost as dangerous as going off with a strange man in a foreign country, but Mindy and I managed to make our rickety way down to the sea. The water was calm and so clear it was like looking through blue tinted glass; we could see silvery fish darting about the sandy bottom. We leapt in; it was as if we were diving into an aquarium. We were splashing about in the water when Baldy completed his slow, ape-like descent down the ladder; he sat on the cement, dangling his feet in the ocean and licking his lips.

“Take off your swimsuits!” he shouted. Since I was well beyond my bad girl tipping point, off went my bikini top. Mindy quickly followed. We frolicked like mermaids, enjoying our very first swim in the warm Pacific Ocean, purposely not looking at Baldy, who stayed dry up on the platform, probably congratulating himself on finally getting what he dreamt of when he invested in an ocean front house in Acapulco.

To Baldy’s evident disappointment, Mindy and I put our bikini tops back on before pulling ourselves up on the platform to make final, second-to-the-last-day improvements on our tans. We didn’t have a chance of achieving a skin tone like Baldy’s (which had an unsettling resemblance to a well-worn loafer), but we had finally managed to shed our corpse-like Minnesota Winter White. Baldy slithered about as we basked, but he didn’t say or do anything overly disgusting besides drool all over himself. He eventually managed to sputter out “Are you staying for dinner?”

Mindy and I had eaten dinner at Carlos’N Charlie’s every night, and it had been delicious and fun and paid for by Fito most of the time. But we were getting close to the end of our Spring Break, and I was obsessed with what would happen next.

I hit the jackpot in Spring Break romances, out on the town and in bed every night with the handsomest man I had ever seen. I was ecstatic with my fairy tale adventure, but inside I held on to a hard nugget of truth: in Fito’s world I was a pretty butterfly, there for him to enjoy for a few days and then gone forever. The day I flew home to Minneapolis, Fito would be back at the El Presidente pool, picking out another pretty blonde to admire him from her front row table at his show and dance with at Armando’s, a new girl to feed oysters to. And then another the next week.

I had no illusions. I knew I meant about as much to Fito as an ice cream cone.

I was not in love, I never thought of myself as Fito’s girlfriend. He was good-looking, drove a fancy car, was a big fish in Acapulco, and that was more than enough. We never had a conversation that went beyond “Would you like another drink?” or “Roll over.” He was singing on stage, we were dancing at Armando’s, or we were in bed. I had no idea of who was inside that tan, handsome veneer, if he had brothers or sisters, where he came from—all I knew about Fito was that he like oysters, drank champagne or vodka on the rocks, and idolized Sam the Sham.

What I did know with absolute certainty was that I was rapidly approaching my expiration date. Late one night as we were leaving Armando’s, another blonde, this one a real Scandinavian, an adorable dead ringer for Elke Sommer in The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming! rushed up to Fito in tears, pounded on his chest with her pretty fists, and wept “Por que, Fito, por que?” Fito yanked himself away from her and responded with a burst of angry Spanish that Miss Sweden seemed to grasp, because she shot back a tearful response in rapid-fire Spanish. I only understood a few words of what she was saying: “Claro, mi amor, pero…” but the whole scene and back story was uncomfortably clear. Miss Sweden was yesterday’s girl. I grabbed Mindy and dashed for the bathroom, where we stayed as long as possible, applying layers of mascara, while the bored ladies room attendant counted up her tips and gave us the stink-eye to get out. When we finally emerged Miss Sweden was gone, Fito was brushing off the sleeves of his shirt and looking annoyed, and Jorge was telling us the car was ready. If I had needed a wake up call, this would have been it, a cautionary tale that prettier girls than me had been tossed to the wayside by Fito.

That night I lay next to a snoring Fito and swore that I would never pull a scene like that. But the memory of that poor girl ate away at me; I was obsessed with the very real possibility that in one of the two nights we had left Fito would stroll into Carlos’N Charlie’s with his arm around a new blonde, leaving me to gnaw on my spare ribs in humiliation. The Spring Break movie in my head did not end with me being publicly jilted. I was determined not to let that happen.

I needed an exit strategy and Baldy’s dinner invitation helped me make one. I decided to let Fito wonder why I wasn’t at his show or at Carlos’N Charlie’s that night. After dinner, Mindy and I would go to Armando’s by ourselves. If Fito were there with a new girl, Mindy and I could dance together, lost in the pounding music, the throngs of people, and the dazzling disco lights. Other men would quickly find us, ask us to dance, and buy us drinks. Thanks for the memories, Fito.

How could I have been so cold-blooded and calculating about the end of a romantic fling? How did I, a 20-year-old from small town Duluth, grasp the social nuances of such an exotic place, and why the hell did I care? I didn’t know the difference between a Studebaker and a Mercedes. I had never seen valet parking or a woman stationed in a ladies’ room in front of a counter full of toiletries, handing you a towel and waiting for a dollar in return.

I will be eternally grateful to Mindy for being not just a good friend but also the perfect travel partner. She was fine with us having dinner at Baldy’s. After we said yes, we’d stay, Baldy made his precarious way up the ladder to give his staff instructions for dinner. Mindy and I spent the rest of the afternoon sunning and swimming, and refining our plans for that evening.

Baldy’s dining room was even darker than the rest of the house, the only light the flickering flames from two immense candelabras that would not have looked out of place in a Dracula movie. Baldy almost vanished into the paneled background, his skin the same shade as the wood. There were also surprise guests. Baldy leaned into the candlelight to introduce us to his friends, two older Mexican men who were several degrees creepier than Baldy, and who were joining us for dinner.

This is one of the few meals I have had that I cannot recall a single thing I ate. Baldy’s amigos spoke just enough English to ask Mindy and me leering questions about our boyfriends, our underwear, and what were thought of Mexican men. When necessary, Baldy translated for them, looking like a successful hunter who has bagged two fat quail and is showing them off to his buddies. As the small silent maid glided around the table, refilling our wine glasses for the fourth time, Mindy and I exchanged the classic girlfriend Let’s Get Out of Here Look: brows raised as high as possible, eyeballs darting to one side. When Baldy chirped “Dessert?” Mindy and I, not knowing if we were going to eat dessert or be it, simultaneously hopped up as if electrified, grabbed our bags, and headed for the door, looking over our shoulders to thank Baldy, express our pleasure at meeting his two awful friends, and protest that we needed to be someplace else immediately.

Mindy and I ran down the hill in the dark; I didn’t look back, fearful that what I would see would be Baldy and friends chasing us down, three elderly zombies, arms outstretched, followed by one of his servants carrying a net. As we dashed down the cobbled street I could hear the men yelling at Mindy and me to come back, when a cab miraculously appeared. We had escaped that weird dungeon disguised as a beach house unharmed.

It was too early to make an appearance at Armando’s. After I got my breath back from running, hyperventilating with fear, and the hysterical laughter that followed, I came up with a new plan. We still had time to catch Fito’s show. If Fito had tired of me, our names would have dropped off the guest list. The maître d’ would shake his head, and I could quietly slip away. We would skip Armando’s and venture out to one of the B-list discos or even head back to our crap hotel for a full night’s sleep. Our Spring Break was almost over anyway; we had only one more day.

But on our second-to-last night in Acapulco, when Mindy and I presented ourselves at the maître d’s stand, we were given our usual warm greeting and ushered down to the front row to watch Fito’s show yet again (“Wooly Boooley! Wooly Boooley! Wooly Boooley!”).

Later, at Armando’s, Fito hollered in my ear, “I didn’t see you at Carlos’N Charlie’s.” I thought quick and yelled back that Mindy and I had eaten at Blackbeard’s, an expensive steak house across from Carlo’N Charlie’s, but his attention had already turned from me to instructing the waiter where to place the ice bucket.

North Country Girl: Chapter 37 — Latin Lovers

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

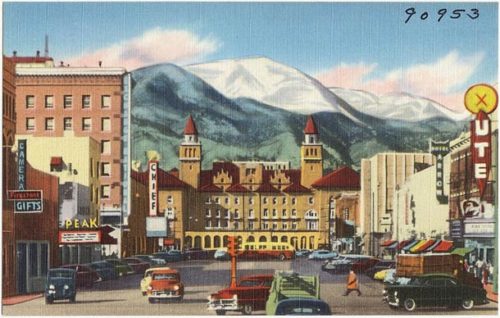

After the fall semester finals, where I managed to squeak out a 78 in vile organic chemistry, I flew to Colorado Springs. I had hoped to do nothing but lie on the couch in my mom’s tiny apartment reading the dumbest romance novels I could find. But my Winter Break was spent prepping my anxiety-ridden mom for her upcoming Real Estate Agent exam (she was still waiting on that second marriage proposal), listening to one sister, Heidi, sob about how much she hated her school and every girl in it, and watching the other, Lani, pack her bags. She was moving back to Duluth to live with our dad. My mother mourned the loss of child support, but she would have gladly sent Lani to the moon to keep her away from her 21-year-old boyfriend. (Within six months, my dad signed some papers and Lani became a bride at sixteen.)

After two weeks of exhausting family drama, I flew back to waitressing, college, and full-on Minnesota winter, which meant no more riding my bike to and from work. I took the city bus to my job waitressing at Pracna, but the buses stopped running at midnight, forcing me to peel off my hard-earned ones for cab fare home, a cab that was always half an hour late; at one-thirty in the morning in Minneapolis there were probably all of three cabs on call.

Click to Enlarge

The January days ended at 4 o’clock, when the dim grey light of winter leached away. Most twilights found me hopping from one frozen foot to the other on the icy sidewalk waiting for the bus and feeling sorry for myself.

I was ignored by my roommate Liz, since I wasn’t fun anymore. Steve, my bad boy boyfriend, stopped calling, probably busy seducing freshman girls and selling bad pills to freshman boys. I looked at my roll of ones, shrunk down to almost nothing after buying plane tickets, paying for my winter tuition, and not working for the two weeks of Christmas break, and I wallowed in self-pity.

One night as I had my face pressed up against the foggy front window of Pracna, peering into the snowy frozen dark in search of my cab, I was rescued by a tap on the shoulder and a voice: “Hey you need a ride to campus?” It was Mindy, one of my favorite sister waitresses, who hustled me out to a car idling in front. Inside that toasty warm car were another Pracna waitress, Patti, and Patti’s very handsome Cuban boyfriend Eduardo, who was driving. Eduardo was at the bar almost every night, waiting for Patti and eyeing the asses of all the waitresses as we swerved around the tables. Mindy was smart, funny, and curvy, with dark, thick-lashed eyes and patent leather black hair. Her best friend Patti was a pretty, pale, flame-haired skinny girl, Lucy to Eduardo’s Ricky Ricardo.

Accepting the ride was not the bad decision. The bad decision was saying “Yeah, I guess so, for a minute” when asked if I wanted to hang out with them at Eduardo’s apartment. It was only a few blocks from my own underheated, creaky dump, where I had to let myself in on tiptoe so as to not wake either my roommate Liz or the crabby landlady beneath us. If I went home now, Mindy and Patti might think I was ungrateful or stuck-up, and I wanted them to like me.

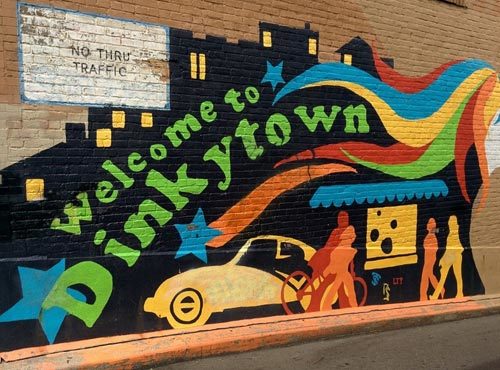

A fancy new apartment building had popped up that fall near campus, in Dinkytown, a neighborhood known for cheap, code-violating housing. It towered like a supermodel over the crumbling duplexes and exhausted garden apartments the rest of us students lived in. I had heard that it was full of rich kids, but had never been inside.

This was where Eduardo lived. His apartment, which he had all to himself, was roomy and new, with shiny kitchen appliances, only slightly stained beige shag carpet, and plenty of heat. In the living room a ratty couch faced a littered coffee table; across the room sitting on shelves made of boards and bricks was the biggest, most complicated stereo system I had ever seen, and hundreds of vinyl records. I drooled a little.

Bob Marley crooned sweetly from out of the chest-high speakers, beers were cracked, joints were lit, and I felt a physical loosening in my chest and shoulders, which reminded me I needed to review the names of the bones in the human body for my physical anthropology class the next morning. One beer and I would go home. Maybe two.

Eduardo sat unnecessarily close to me, our hips touching, and in his charming accent said, “I apologize for my poor furnishings.” His father gave him a generous monthly allowance, which he preferred to spend on beer and pot and albums, rather than bookshelves (or books: I didn’t see a single one).

Eduardo’s family had managed to flee from Castro with quite a bit of their money. Although not nearly enough of it according to Eduardo, who held me captive for several more beers that night with his fascinating if slightly biased history of the Cuban Revolution as seen through the eyes of the very people who inspired Castro and Che to reach for their revolvers. Mindy and Patti, who had heard this tale countless times before, indulged in Pracna gossip till they passed out. Way too late, I finally thanked Eduardo and stumbled home through three-foot snowdrifts, thinking, well that was fun, I needed that, all work and no play and who wants to be dull? I promised myself once was enough, I wouldn’t make it a habit.

I ended up at Eduardo’s apartment the next night and the one after that.

Mindy, Patti, and Eduardo should have been a cautionary tale for me. All three of them were on academic probation after spending most of the fall semester listening to Bob Marley and smoking weed. Mindy was the only one who seemed concerned, but the textbooks she lugged to work and then to Eduardo’s and then back home remained uncracked. At least she bought books. Eduardo had better things to do with his money, keeping the four of us in Grain Belt beers and pot.

Eduardo wasn’t worried about being on probation. His family had just parked him at the University of Minnesota until he was old enough to join their mysterious business. If he flunked out, they would find a place for him at a college in Mexico or Spain, one that didn’t care about a transcript. Patti had decided that as the future Señora Eduardo, she didn’t need a college education either and rarely went to any of the three classes she had registered for.

Somehow I managed to keep my grades above water while doing what most 20-year-old college kids did then and still do: get shit-faced every single night. I just didn’t sleep much. I’d make it back to my dingy apartment and my disapproving roommate Liz in the morning in time to shower and change before trudging through the snow to my eight o’clock class. I told myself that as long as I never missed a class, I was fine. And I wasn’t spending my hard-earned money at an after hours club; I was just hanging out, in a warm place with very attractive people, while three little birds assured me that everything was going to be all right.

Eduardo was delighted to add a blonde to his collection; he was always stroking my hair, resting his hand on my thigh, holding a joint to my lips. I didn’t take it seriously, as Eduardo flirted with Mindy and all the other Pracna waitresses. Then one night, when my brain had punched out for the evening and Patti and Mindy had fallen asleep on the couch to the lullaby of “No Woman No Cry,” the handsome Eduardo took me by the hand and led me into his bedroom. The sex, even in my stoned and drunken state, was unremarkable, and I regretted it well before Eduardo rolled off of me and started snoring.

I have no excuse for my awful behavior outside of callow, stupid youth. I had broken the girlfriend code. I confessed to Patti the next day, as we were changing into our uniforms at work. I steeled myself for tears and yelling and the mass disapproval of the entire Pracna waitstaff, which thrived on gossip. What if I had to quit my job? Guilt and dread gripped my head and stomach in a vise but Patti shrugged it off as if I had done nothing worse than help myself to a beer from Eduardo’s fridge. She had absorbed enough of the Latin male mindset to know not to make a fuss about such a thing; she had her eye on the prize. Patti did ask me not to tell her best friend Mindy, and made sure that I never had another opportunity to be alone with Eduardo.

I was relieved and grateful that I had not been banished from Eduardo’s. I had grown to hate my charmless, chilly duplex. Liz and I lived directly above our witchy, man-hating landlady, who thundered up the stairs with her own key the moment she heard anything “suspicious,” threatening that if a boy as much as set foot on our front stoop Liz and I would be tossed out on the street where we belonged.

A brand new apartment with a cute shiny alcove kitchen in an elevator building with plenty of heat was all I needed of luxury, even though there was barely a stick of furniture besides the rumpled couch suffering from cigarette burns and many spilled drinks and that massive stereo system; in the bedroom a double mattress rested on the floor, with sheets that looked like they had never been changed, even after my escapade with Eduardo.

My drunken, stoned nights at Eduardo’s lifted me off the treadmill of work and school and the awfulness of trudging to both through the sleet, snow, and freezing temperatures of a Minnesota winter, a winter that set records in how high the drifts were and how low the thermometer plunged. Those three little birds had obviously never been through February in Minnesota.

I had thrown myself back into my hectic work schedule, taking as many shifts at Pracna as I could, closing up Saturday nights and ten hours later cheerfully serving Bloody Marys to people who worshiped at a bar. The church people arrived at one, still dressed in their Sunday best and ready for the weekend’s last bender.

Winter drives Minnesotans to drink, to search out the warmth of bars and other people, and Pracna, with the golden glow of its oak bar, polished by generations of elbows, profusion of fake Tiffany lamps bestowing flattering spots of color, and attractive and professionally friendly waitresses, was constantly packed. My shoebox stash was replenished and continued to grow, as fast as if the one dollar bills in there were mating and reproducing.

One snowy sub-zero day I was counting up my money like Scrooge McDuck and remembering that a year ago I was living on off-brand fish sticks and instant ice tea to scrape together the cash for a one-way plane ticket so I could spend six days in an old folks home in Daytona Beach.

Now my junior year Spring Break was coming up, and I was awash in dollar bills. I could go on a vacation that did not involve rooming houses or hitchhiking. My pal Liz had not mentioned any Spring Break plans of her own; we had gone our separate ways, passing at odd hours through our shared apartment, occasionally backing out of the already occupied bathroom, or silently sipping instant coffee in the morning. Patti was going to Florida with Eduardo to meet la familia. That left Mindy, who was dying to get away for a week somewhere your snot didn’t freeze the second you stepped outside, where you could wear sandals and a bikini, drink piña coladas, and meet boys. That sounded good to me too.

Mindy brought me brochures from a student travel company that offered Spring Break trips to Montego Bay or Acapulco, $299 for airfare and hotel. I voted for Jamaica. I had spent months listening to Bob Marley while smoking weed at Eduardo’s; I looked at the photo of a white sand beach and calm turquoise sea and pictured myself right there with a big blunt and a handsome Rastaman. But another Pracna waitress told Mindy that the beaches in Jamaica were overrun with packs of ferocious, tourist-eating dogs. Mindy was terrified of dogs; even my mother’s miniature poodle Shay-Shay would have sent her scrambling up a palm tree. So instead we flew off to Mexico on a chartered flight, packed with students who couldn’t wait to start drinking to wretched excess. Mindy and I navigated the flight and the bus to the hotel with only minor pawing and mauling from male Spring Breakers.

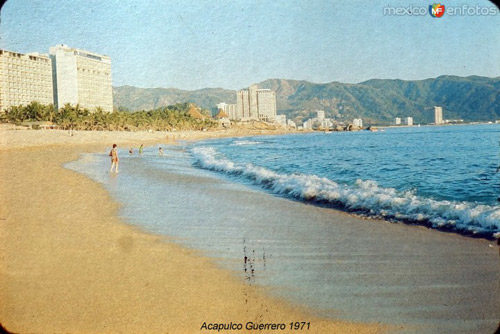

The bus disgorged us under a torn awning attached to a three-story, mildewy green building. Mindy and I stood on the sidewalk in the noon Acapulco heat, looked at the hotel and looked at each other. In no way did this hotel resemble the one in the brochure except for the name, which was La Casa Cheapo, or something similar. The sullen, non-English-speaking guy at the front desk glanced at our reservations and tossed us a big metal key attached to a heavy weight etched with our room number. The elevator doors opened to release a toxic combination of stinks and a pack of boys too hung over to even leer at the new meat. Our room did not overlook the famous Acapulco beach, but the busy, noisy Avenida Costera. The air conditioner, thick with dust, refused to work; when we opened the one tiny window clouds of car exhaust were sucked into our room. There was a urinal cake perched on top of the toilet. After emptying the drawers of roaches, we unpacked, put on our cute bikinis, and headed down to the pool, which looked like pea soup: a clot of vomit floated in one corner and two broken patio chairs in another. Mindy was about to cry. I was mentally comparing this dump to the luxury hotel my family had stayed at during a dental convention, and I snapped to a decision: “We’re going to the El Presidente.”

We rushed down the Avenida Costera to the El Presidente pool, which was exactly as I had remembered it from that trip, eight years before, the scene of so many drunken dental hijinks. Shiny sea blue tiles surrounded a huge, sparkling pool, with that eighth wonder of the world, a swim up bar. On all four sides of the pool area Tiki huts were serving oversized margaritas, frosty Sol beers, and drinks in coconuts. Rows and rows of lounge chairs held dozens of college students, boys and girls in various shades of Spring Break, from the just-arrived paper whites, to the should-have-gotten-out-of-the-sun crimsons, with a few lucky souls who can get a tan in seven days scattered about. Prominently displayed above this wonderland was a sign FOR GUESTS OF THE EL PRESIDENTE ONLY.

Mindy said, “If I have to go back to that hotel, I’m going home.” We agreed to live dangerously; if we had to, we could just spend the day getting thrown out of different hotel pools. We found two free lounge chairs and tried to look as if we belonged there.

Mindy and I were busy rubbing Coppertone on each other when two shadows fell over us. I looked up to see what was keeping the sun from bestowing some kind of glow to my pasty Nordic skin. There stood two Mexican guys, fully dressed in billowing shirts and tight pants. One looked like a younger, pudgier Cantinflas, smiley and slightly goofy. The other could have Eduardo’s taller, better-looking, older brother. He had dark brown, shoulder-length wavy hair and eyelashes longer and thicker than any offered by Maybelline; his gleaming white shirt gaped open to reveal a deeply tanned, muscular chest adorned with a thick gold chain and dangling charms: a small clenched fist in ivory, a blue eye, a half-dollar sized gold medallion. The guys asked if we wanted a drink (“Why yes, thank you!”) and introduced themselves. The tall one was Fito Giron—didn’t we recognize the famous singer? We had to have seen Fito’s poster in the hotel lobby! Fito was the star of the show at the El Presidente lounge; the other guy, the one who was doing all the talking, was Jorge, Fito’s full-time gofer and friend.

Rum and coconut drinks magically appeared and Fito scribbled on the bill offered by a fawning waiter. Mindy and I thanked Fito for our cocktails and apologized to Jorge for our ignorance. No, we hadn’t seen Fito’s act, we had only gotten to town that day. While Fito posed, hands on hips, chin cocked, hair tilted into the wind, Jorge insisted that we had to go that night to hear Fito. He, Jorge, would put us on the guest list. What were our names and room numbers?

Ten minutes trespassing and we were busted. We confessed that we weren’t staying at El Presidente but down the Avenida at the no-star hotel des estudiantes. This was shrugged off by Fito. “No importa,” he said as he looked down and locked eyes with me. Jorge was quick to jump in. “Don’t worry, your names will be on the list, you see Fito’s show and then we all go dancing!” Jorge wrote down our names, and Fito swooped down on me like a hawk to plant a kiss on both cheeks, then turned and left with a backward wave.

I was bewildered and amazed and giddy at what had just happened. We had landed dates in our first hour of Spring Break, we had free drinks in our hands, and we had successfully snuck into the El Presidente pool. To be sure that we were not at risk of getting the bum’s rush, we called over the waiter for more coconut rum drinks; he scurried over like a Mexican Groucho Marx, took our order, and let us know that everything was on Fito’s bill.

North Country Girl: Chapter 35 — The High Cost of College

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

My romance with our dorm’s drug dealer was torrid, tempestuous, and exhausting. It was almost a relief when school ended in June and Steve went off to Outward Bound, to be molested or not, and I went to spend my first summer in Colorado Springs, where my mother had moved in pursuit of her second husband (third if you count her teenage elopement with Bill Bailey, a traveling salesman). My mom, my two sisters, both of them unhappy with the move and miserable in their new schools, and most of our French Provincial furniture from our six-bedroom house back in Duluth were shoehorned into a two-bedroom apartment that had all the character and quality of a roadside motel. Skyway Village Apartments did have a pool, where during the day I sunned and read and tried to ignore our across-the-hall neighbor who kept plopping down next to me to ask why I didn’t own any bras. A few blocks away from Skyway Village Apartments was a restaurant called Mr. Steak, which hired me on the spot before I realized what a complete shithole it was.

Mr. Steak was a grubby, sad place targeted toward unsuspecting tourists on a budget, tourists on their way back from ruining their cars’ transmissions and brakes making the crazy drive 13,000 feet up the top of Pike’s Peak and back down again. The steaks at Mr. Steak looked exactly like rubber dog toys, the baked potatoes were hard as a rock, and most of the lettuce in the skimpy salad was brown. No wonder I so often went home empty-handed. It was amazing that people actually paid to eat that crap, and I should have been grateful that they didn’t slug the waitress who brought it.

I went back to Minneapolis my sophomore year with even less pocket money than the previous fall. I was not returning to the dorm, but to the thrill of a completely unsupervised off-campus apartment. After much cajoling of all parents, my pals Nancy, Liz, and Sarah and I were allowed to leave the protection of the college dorm and move into that rarest of all things, a four-bedroom apartment. My father only agreed because the rent split four ways was less than half of what the dorm cost; I could forage for my own food, or have Steve kill me a squirrel.

Despite the money he saved, my dad was suspicious of the whole set-up and took to making unannounced pop-in visits every time he was in Minneapolis. Early one Sunday morning his pounding on our door woke everyone up and forced us to herd a quartet of half-naked, hungover boyfriends into the farthest back bedroom before putting on robes and nighties and coming out to say hello to Dr. and the second Mrs. Haubner.

We eventually acquired a fifth roommate, my friend from high school, Gretchen. Gretchen was a long-haired hippie chick, with a big heart, a dry wit, and a hooting laugh. Gretchen was also going through a bad time, which we should have suspected when she showed up at our Halloween party wearing only a grass skirt, her breasts painted (with house paint) as twin red, white, and blue targets. Her bad time erupted into kleptomania: Gretchen was a preternaturally talented shoplifter. She was never caught, although after I watched her pull t-bone steaks out of her pants I never again risked going to the supermarket with her. Gretchen slept on the living room couch on top of and under dozens of articles of clothing, all with the price tags still attached. The day Gretchen came back to our apartment proudly brandishing two huge silver candlesticks she had boosted from a Catholic church was the day we put her on a bus back to her family in Duluth. Gretchen did recover, and ended up in Yemen working for the Peace Corps.

My meager savings from waitressing at Mr. Steak quickly evaporated. I found a job at Lancers, a ginormous warehouse of a store, with acres of stacks of jeans—Levi’s, Lee’s, Wranglers—plus weird off brands, in hundreds of colors, styles, and sizes, from pants that would fit a smallish dwarf to ones with a 50 inch waist and 38 inch inseam. My job was to follow customers around, not to help them find a needle in this denim haystack, but to pick up every pair of jeans they had touched, shake them out, refold them, and arrange them back in a perfectly aligned stack of pants. The $2.50 hour I was paid was not enough to make up for the intense hatred I had for every person who walked into that store; I knew their sole intention was to mess up my piles of jeans.

After my first week at Lancers, I realized that everyone was stealing clothes from the joint: the manager, the sales clerks, the delivery guys who dropped off another thousand jeans to be folded and stacked somewhere, and probably even the mailman. Every day more jeans were stolen by the staff of Lancers than were sold to customers. While I would have gladly burned Lancers to the ground, I resisted taking anything until the manager told me that everybody thought I had been planted there by Mr. Lancer as a spy. To prove my innocence, I stole a pair of baby pink, brushed denim elephant bells that billowed around my platform shoes; the three-button fly ended palm’s width below my navel. There were adorable and fit me so perfectly I felt not a twinge of guilt.

The tiny paychecks I got from Lancers managed to cover my living expenses, even after Gretchen left and I could no longer save money by dining on stolen groceries. But I was not earning enough to afford a Spring Break trip to Florida, the Shangri-La of every Minnesota college student. For me, Spring Break was the impossible dream, a dream I indulged while trudging through snowbanks to campus and back, or spending untold hours folding jeans.

As a kid, all winter long I bundled up and went out even in near-blizzard conditions to build snowmen and make snow angels and join the neighbor kids for snowball fights, until the indigo four o’clock twilight fell and I couldn’t feel my fingers or toes and required several mugs of hot cocoa to thaw out. As a teenager winter meant high school ski trips, with shared cigarettes on the chair lift, Fitgers beers bought by the kid with the best fake ID, and the erotic possibility of sitting next to a cute boy on the bus ride home. All through my childhood and high school years winter had enough pleasures to totter on the border between bearable and enjoyable.

For students at the University of Minnesota, the only good part of winter was the anticipation of Spring Break, a week away from snowdrifts and wet socks and chapped cheeks and lips. A week dedicated to the best part of college: boys and drinking. As I folded jeans, I imagined myself wearing a cute bikini and holding an umbrella drink, surrounded by handsome college guys. But every time I cashed my paycheck, I was reminded that it was only a dream.

My roommate Liz, however, was determined to enjoy a real Spring Break, and finally convinced me that for our sanity, the two of us needed to get away somewhere it wasn’t 10 below. Liz claimed to also be short of ready cash (I believe she said this in solidarity, as her father was a prominent Mayo Clinic heart specialist).

Liz and I pooled our money and devised a plan for a Bargain Basement Florida Spring Break. We would buy one-way plane tickets to Daytona Beach, stay at the cheapest place possible, get guys to buy us drinks and meals, and then hitchhike back to Minneapolis. Yes, we were that young and stupid.

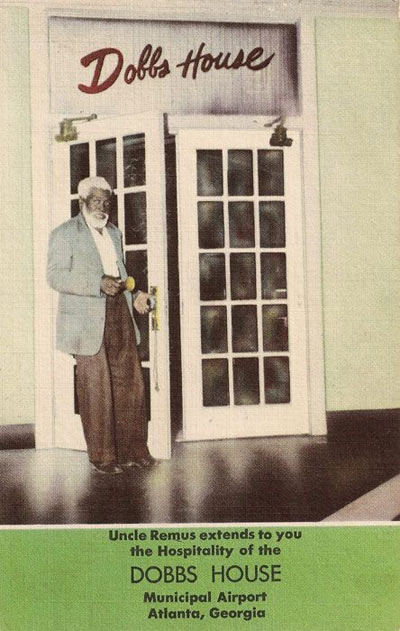

On our flight to Florida, we changed planes in Atlanta with just enough time to have a cup of coffee and split a plate of eggs. A gracious white-bearded black man ushered us into to Dobbs House, the airport cafeteria, where every wall was decorated with murals of Br’er Rabbit and friends in a black-face minstrel style that made Disney’s “Song of the South” look like a contender for an NAACP award. As we sipped our coffee and passed the fork for our scrambled eggs, we were surrounded by the most extreme, pop-eyed, thick-lipped depictions of Uncle Remus, who was himself surrounded by grinning, nappy-headed, raggedy black children. I am sure they had only recently taken down the “No Negros Served” sign: all the customers were white, all the waiters black. Sitting in this homage to racism was shocking; it felt evil, oppressive. (When I was living in Atlanta I could not find a single person who had a memory of these murals, but my pal Liz will attest that they were there.) We choked down our breakfast and ran to catch our plane.

We splurged on a taxi into Daytona Beach and discovered that every motel set their Spring Break prices under the assumption that between eight to ten kids were smashed into a single room. There was nothing Liz and I could afford, as we did not have another six roommates to split the cost of a motel with.

After hours trudging from one place to the next, looking longingly at cute drunk boys and bikinied girls playing chicken in motel pools—just like I had imagined!—we ended up at the Palmetto, an old-fashioned rooming house that had one tiny twin bedded room left. After we had paid our fifteen dollars a night, Liz and I discovered that we were the only people under 80 in the joint, something we should have realized from the pervasive old person smell. The ramshackle house had three bathrooms, one on each floor, which were shared by tenants of both sexes. In a fit of madness on a rainy day, Liz and I locked ourselves in the third floor bathroom, where we dyed my hair blonde while an old man pounded relentlessly on the door, claiming he had to poop.

Worst of all, The Old Folks Arms had a curfew: the front door was locked at midnight. What were those ancient, arthritic codgers getting up to in the middle of the night that they needed a curfew? Liz and I examined the rickety fire escape and decided that we did not want “Spring Break Coed Dies in Fall” to be a headline in the Minneapolis Tribune. We were doomed to be the Cinderellas of Daytona Beach, unable to stay out too late at the ball.

As it turned out, our Spring Break nights ended well before twelve. At nineteen, Liz and I were not old enough to drink legally in Florida. And contrary to what we had assumed, bouncers did not happily allow cute underage girls into their bars.

We spent our days on the famous Daytona Beach, trying not to get run over by the 70,000 cars and trucks zooming across the sands, driven by drunken, cat-calling yahoos. We were determined to go back tan, proof that we had spent Spring Break in an exotic tropical locale. We managed to achieve not too painful sunburns.

We did accomplish our main goal, to meet boys, some of whom actually took us out to nice restaurants, where Liz and I were spared the indignity of being asked for IDs when we ordered our before-dinner White Russians. On our last night we were picked up by two boys from Ole Miss, who had almost impenetrable accents (“Carfish? We’re going to eat carfish?”). We rode in one of their daddy’s Lincoln Continental deep into a pitch dark bayou (“Did he say the restaurant is a fur piece?”). As we bounced around the rutted road, insects smashing by the thousands on the windshield, Liz turned to me and mouthed “Deliverance,” which we had seen the year before. I shot her back a should-we-jump-for-it look just as we pulled up to a shack where I had my first and most delicious catfish and hush puppy dinner and even managed to get tipsy on Dixie beer, as no White Russians or any other cocktails were served.

Liz and I had to cut our Spring Break short, as we estimated it would take us a day and a half to hitch-hike back to Minneapolis in time for our Monday morning classes. After our bayou adventure, we decided we needed to be on guard on our way home.

“One of us should always stay awake in the car.”

“We’re not going to get in if there’s more than one person in the car.”

“No accepting drinks from the driver.”

At seven in the morning Liz and I walked to the curb of the main road heading north, stuck out our thumbs, and immediately got a ride. It was a yellow two-door sedan, dented and rusty, with as expected, a male driver on his own. He leaned over, pushed the front seat down, and opened the passenger door. I clambered in the back so long-legged Liz could have the front. From where I sat, I could see the driver’s pale nape and unfashionably short hair; the rearview mirror reflected a slice of his eyes, shifting back and forth.

“Where you girls headed?”

I had a fleeting fantasy that maybe this guy was somehow a solo Spring Breaker, a fellow Golden Gopher, headed back up north straight to Minnesota. I said “Actually, we’re going all the way to Minneapolis. You wouldn’t—”

Liz jumped in. “No we’re not. We’re getting out here.”

“What Liz, no, we—”

“We’re getting out here!” she yelled while turning around to glare at me, then threw her door open. The car was still moving. The pasty driver hit the breaks, and Liz scrambled out, throwing the seat forward and pulling me out of the car with one motion. She slammed the door, turned and marched back the way we had come.

I caught up with her. “What the hell Liz—”

“He had no pants on.” This fruitcake was driving around Daytona Beach at seven in the morning dressed only in a tee shirt. He must have thought he hit the pervert jackpot when he came upon two blonde nineteen-year-olds looking for a ride.

Liz and I sat on the curb for a minute to pull ourselves together. We had to get home somehow and we had less than $30 between us. Neither of us were about to call our parents; I don’t know how they would have gotten money to us anyway. We waited until we felt sure the pale creep was gone, stood up, and stuck out our thumbs again. The goddesses of youth and hitch hikers smiled upon us: we made it from Daytona Beach to Minneapolis in three rides, all of them with nice guys driving alone, wearing pants. Our third ride was a very concerned dad from Stillwater, Wisconsin, who bought us breakfast and lunch and insisted on driving us all the way to our front door, where he waited until he saw we were safely inside before driving away. God bless you, sir.

In June I shipped my bike out to my mom in Colorado Springs, so I could work somewhere, anywhere other than Mr. Steak. My family’s life at Skyway Village had become even more chaotic. Alimony and child support checks from my dad arrived on a schedule of their own and only after several screaming, threatening phone calls from my mom. A second marriage to the man she had followed out to Colorado did not seem to be happening anytime soon, as my mom’s intended, a former pillar of the Catholic Church and father of six, could not get his wife to divorce him and no fault divorce had not yet been invented. Heidi, my youngest sister, had spent the school year being bullied, beaten up, and having her head shoved in the toilet in the girls’ washroom and probably could have used professional counseling; fourteen-year-old Lani was working illegally at Kentucky Fried Chicken and dating the manager.

I would have been happy to waitress ‘round the clock to get away from that mess, but settled for the eight p.m. to two a.m. shift at Hof´s Hut, a blindingly bright downtown diner a thirty-minute bike ride from Skyway Village Apartments.

During the day, Hof’s Hut was a run-of-the-mill vinyl and stainless diner, breakfast served all day accompanied by bottomless white china mugs of coffee. At night, its neon sign and bluish fluorescent lighting drew an ugly bunch of customers. There were drunken GI’s and even drunker cowboys trying to sober up over hamburgers and chili and cheese omelets before driving back to barracks and bunkhouses. There was always at least one table of heavy-lidded junkies unscrewing the salt shakers to sweeten their coffee. Worst of all were the completely wrecked underage cadets from the Air Force Academy, who even at their most intoxicated believed in their flyboy status. They shoved their hands up my skirt when I refilled their coffee and thought it was hilarious to stagger into me, steadying themselves with a hand grasped firmly on my left tit. They puked in the men’s room, on the front sidewalk, and in the parking lot, and I felt so sorry for the Mexican bus boys and the Sisyphean task they faced every Sunday.

One Saturday night, after six hours of scooping up sticky quarters and grimy dollar bills, wiping down ketchup bottles, and wrestling clammy hands off of my thighs, I wheeled my bike out the back door of Hof’s Hut and headed home, down broad, deserted but very well-lit Colorado Avenue. That half hour of thoughtlessly, rhythmically, pumping my legs, gliding through the warm, quiet night was the one moment of calm in my life. I had just started to relax, loosening up my shoulder muscles when out of the corner of my eye I saw a gleam of white and recognized it as a human being, a man, a man with absolutely no clothes on, who dashed out after me. The adrenaline hit me faster than one of Steve’s Black Beauties and I threw the bike into high gear and Tour de France mode. I cracked my neck back, watched my pursuer dwindle into the dark and wondered: could that somehow be the pantsless guy from Daytona Beach? How had he tracked me here in Colorado Springs?

At least I was making more money than I had at that outpost of hell, Mr. Steak. Drunks tend to overtip cute waitresses. I needed every quarter. I had registered for a grueling schedule of courses for the fall and wanted to save enough money so I could just concentrate on my studies and not have to serve slop to freshmen or fold hundreds and hundreds of Levi’s.

In August Liz called me to report that over the summer our other two roommates decided they had better things to do with their lives than go to college and had dropped out.

“So I drove up to Minneapolis and there were hardly any apartments left, but I found one for us.”

I needed to send her a check to cover my half of the security, first month’s rent, and deposits for telephone and electricity. I scratched down the horrifying large amount and got the OK from my mom to make the dreaded long-distance call. My dad picked up for once; the phone was usually answered by his dumb, heavy-breathing second wife who always lied about him being home. I rushed through the small talk, not caring about what milestones his two toddlers had achieved.

“ I need you to send a check to Dr. Hepper in Rochester, he’s already paid for everything for our new place.”

A few moments of silence passed.

“The divorce agreement says that I have to pay for tuition and dorm. Are you going to live in the dorm again? I’m not paying for you to live in an apartment.” He said the word apartment when he meant whorehouse. My heart sunk. I realized that we had not hidden those boys well enough during my father’s Sunday morning pop-in visits. I hung up, furious.

“Yeah, he’s a jerk,” my mom shrugged. I took a big chunk of my summer savings, bought a money order at the post office, and sent it off to Liz’s dad.

On Labor Day I poured coffee for one last drunk cowboy, cleaned my final ketchup bottles, and turned in my Hof’s Hut uniform. I kissed my mom and sisters goodbye, and my bike and I flew back to Minneapolis.

Gimme a Break!

Iwas thinking the other day of everything that’s changed since I was a kid. Some people don’t like change, but I’m not one of them. To believe something shouldn’t change is to say it can’t be improved, and I don’t know anything that can’t be made better with creativity and work. Of course, with every rule there is an exception, and the exception to this one is spring break. Spring breaks have changed a lot since I was a kid, and not for the better.

When I was growing up, schools held their spring break on Holy Week, culminating in Easter. Sometimes this was in March, and sometimes in April, on the first Sunday after the first paschal full moon following the spring equinox. Don’t ask me what a paschal full moon is, just take my word that Easter doesn’t happen until it does.

In those days, spring break provided the interlude between cold weather and warm. We would carry our sleds down to the basement and carry up our bicycles; remove the storm windows and store them in the barn; rake the winter debris from underneath the bushes; bring down the box fans from the attic; tune the mower; then haul the swing from the barn to the front porch. It was a working vacation, but still beat school all to pieces.

Today, families from Indiana, my home state, take their kids to Florida, but Florida wasn’t even invented when I was little, so we stayed home and worked. Our respite came on Good Friday, when my mother would bundle us in the car and drive us to Beecham’s on the town square to buy a suit for my brother Glenn who was six inches taller than the rest of us and got a new suit every Easter while we, his hapless brothers, wore his suits from Easters past. Four pencil-thin boys in dark-gray suits, our hair slicked down with Vitalis, looking like a gospel quartet, like the Dixie Hummingbirds, except for being white and from the north. On Saturday evening we dyed Easter eggs, then went to Hook’s Drugs five minutes before it closed to buy marked-down chocolate Easter bunnies, jelly beans, and plastic grass. We would stop at St. Mary’s Catholic Church on the way home for our weekly confession, enter the confessional to shout out our sins to Father McLaughlin, who was deaf as a rock, then drive to Burger Chef for a fish sandwich.

The spring-break-in-Florida craze was just taking hold when I was in high school, when the Piersons, who lit their cigars with $20 bills, flew — yes, got on an airplane and flew! — to Florida where they sat on the beach an entire week, then returned to Indiana darker than chocolate Easter bunnies. Now the Florida trend includes everyone but the Amish, who sensibly stay home while the other parents pile in their cars on Friday after school and drive through the night to Panama City, where they arrive the next morning, exhausted, crabby, and hating their children. They do this for those same children, who, if they don’t go to Florida, whine about being the only children left in town, bored stiff, friendless, ridiculed for being poor and having stupid parents.

When I was a kid, parents didn’t care what their children thought of them, so children had no leverage and had to do what their parents said. Then self-esteem was invented in the 1980s, the balance of power shifted, and parents had to keep their children happy and let them do whatever they wanted. Father McLaughlin would fall over dead if he were hearing confessions today.

The problem with spring break today is that it’s planned to the nth degree. It now has a point, to relax. But when relaxation is a goal it becomes a task, a grim obligation,like a prostate exam. Hence the white-knuckled drive to Florida, the insistence on fun, the making every moment count, the reckless spending, then returning home exhausted. Getting exhausted at home didn’t seem nearly as tiring, and I would return to school, my mind renewed, crossing off the days until summer and my emancipation.