The World Isn’t Finished (and Neither is the Car)

Ellen Pyle

November 24, 1934

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

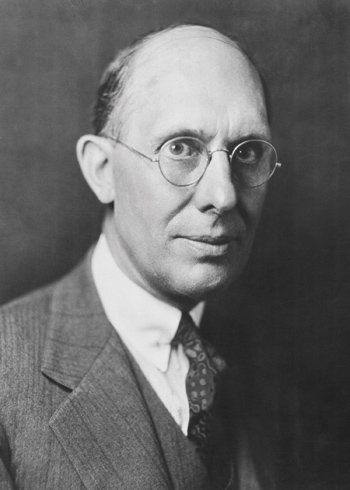

Charles F. Kettering was head of research for General Motors from 1920 to 1947. The holder of 186 patents, he was best known for inventing the electrical starter, leaded gasoline, Freon gas (essential for air conditioning), and a system for using color paints in mass-produced cars. In this article written for the Post during the dark days of the Depression, Kettering invites readers to take the long view, reminding them that life (and the auto business) is constantly changing for the better. It was an important message from a chronic optimist.

A man said to me the other day, “I don’t see what you can do to improve the automobile. It looks like perfection to me.” I said, “I hope it isn’t, because my job is gone if it is.” And that’s a fact. Most of our jobs would be gone if the products of the industries in which we are engaged should be adjudged perfect. Because then it would just be a question of employing enough men to produce the perfect thing. In the reorganization of business on this basis, not more than 30 percent of us would have employment.

In these days, as always, the most important fact from every angle is that the world isn’t finished. This holds in every realm — in business, in matters of unemployment and economic recovery, in the organic world, the psychological, the spiritual, the personal, and all others. Growth is the essence of life, and evolution functions in business as in biology. New standards evolve, and new human needs, new products, new jobs, just the same as new living forms do. Of course my work has been limited largely to the automotive field. But that’s a big world in itself, touching many others and exemplifying many truths. If the world had ever stood still, we might still be in the age of the dinosaurs and pterodactyls. But there aren’t any of these creatures around. The principle of the thing, as Darwin showed, is that the world moves on, that Nature is never satisfied with existing forms, but is always trying for new ones. The world has moved on from the first living cell to the modern man. It is moving on toward higher living forms and better social conditions. It will continue to move on toward a higher standard of living for everybody, toward a greater degree of beauty, strength, and perfection in all things.

The Future Is Bright

We in the automobile business believe that time is no kinder to us than to anybody else. But we think we try to recognize it more. We bring out yearly models on the theory that business and social conditions progress as producers hit a constant rate of improvement. We believe that for the next 10 or 20 years at least we can bring to you an improved and a better automobile. I think I can illustrate the basis for my belief by considering the three basic materials with which we work — rubber, petroleum, and steel.

I always admired the man Dunlop, because I think that anybody that had the nerve to propose a rubber tire to run on the ground when everybody knew that steel was the only thing that would do, must have been a man of distinct nerve and bravery. He planted the idea, and the simple rubber tube that he made progressed through various stages of evolution, until, a half-dozen years or so ago, the industry turned out the balloon tire. The lifespan of a tire went from 3 and 4 thousand miles up to 15 and 20 thousand. We began to experience a new ease in riding and a new safety in driving.

We owe a great debt to the rubber people. Yet I don’t think their job is finished. And they don’t either. In the future, we can expect tremendous improvement, not merely trivial additions, but evolutionary — and I might say, revolutionary — developments in tires.

In regard to petroleum, we have always known it to be a marvelous fuel, but in the past four or five years we have begun to recognize that the possibilities of developing power from the internal combustion engine are just on the verge of development. It is a fact that our best automobiles today deliver under normal driving conditions only about 7 or 8 percent of the total energy in the fuel. There is actually enough energy in one gallon of trade gasoline to propel a small car from Chicago to Detroit, some 300 miles, instead of the 20 miles attained.

In steel, we used to believe that the elastic limit was about 80,000 pounds per square inch, which is to say that if we pulled a square inch of the best steel we used to have with 80,000 pounds’ pressure, it would go back to its original position. The place where steel fails to go back is called its elastic limit. But then we came along with better steels, and the elastic limit went up to 100,000 pounds per square inch, and finally to 125,000 pounds, and today we are using steels under pressures of 300,000 pounds per square inch and they are standing up perfectly. Nobody knows where the limit will finally be found, if indeed it is ever to be found. Ten years from now, we shall be thinking thoughts and dreaming dreams not even in our conscious thought now.

Nourishing an Idea

Ideas always do go on to a harvest. They are like corn — first the seed, then the blade, then the stalk, then the flowering, then the grain in the ear. The parallel holds in many ways. When a man travels, observes, wonders, and questions about things, that is like plowing the land, the seed bed of his mind. Then the seed must be planted. Of course the rains may come and wash out the seed, or the hogs root it up, or the sun bake and dry the kernel. If the shoot does push through, the weeds may choke it, or the high winds rip it out of the ground, or the drought kill it. But if a man keeps on planting corn he will eventually reap a harvest.

I’ve seen this work out so many times. One submits an idea to a committee. If the committee is in an unprogressive industry not used to new ideas, it will probably brush that new idea into the wastebasket; nevertheless, one will have plowed a little ground, made it ready for the planting of the idea. One goes on submitting it, and the committee keeps on pushing it off the table, and pushing it off and pushing it off, until, perhaps, after two or three or four years, somebody says, “Hey, wait a minute. There’s something in that.” Then one may be sure that the seed of the idea has sprouted, that the shoot has pushed through the ground. All one has to do then is to keep the weeds down, work the land and the crop. The seed will yield a harvest of a thousandfold or more.

That is Nature, and one may be sure of the harvest, though if it is a big idea he is planting, much time may be required. The idea of the automobile was simple enough, but it took a long time for it to grow into its present magnitude. The world seldom sees that harvest until it starts to materialize, because it’s a new thing that the world has never heard of and doesn’t believe in. But when people do begin to see the harvest, they rally round and get all enthused and start making the thing a whole lot bigger than it really is. With one voice they all say, “How blind we were not to see this thing in the first place.” They start out to make a hero of the man who promulgated the idea, and build monuments to him after it is too late to do him any good.

The Nature of Work

In business, as in all things, we must swing back to the old position of being guided by Nature. Because life is just that way: That is all. As ideas are like seed corn, so wealth itself is like the harvested ears. One has to work to produce wealth. You can’t wave a wand and take it out of a hat. In order really to prosper, you have to study your land, perhaps fertilize it, then plow it, plant it, scratch the crust, work the crop, keep the weeds down and guard against insects, blight, and marauders. After the sun has warmed and rains watered, there is the labor of harvest. The man who follows this life and knows that it’s his job, is happy in it.

Of course, here’s where the business of living really begins to come in. You know the story of the old mule that used to pull the slag oar out at the ironworks. The company became prosperous, and decided that they ought to have a little steam locomotive to pull the slag car. They turned the mule out to pasture. The first day he seemed to enjoy it; the second day he hung around the gate; when the man came to work on the third day, they found the old mule leaning up against the slag car. Maybe the mule didn’t exactly enjoy pulling the slag car, but it was his job and he was lost without it. Most men, like the mule, like to do what is in them to do. The farmer has to have his hands on the plow handles; the sailor must live around the sea; the painter must paint; the mechanic work with his monkey wrench; the racing driver work to win the Indianapolis races.

What is more, there is a certain natural rhythm in work, as one can see by watching a blacksmith at his anvil, or a sower flinging the seed with a motion nicely tuned to his stride, or several hoe hands working in the field in natural unison of movement. It is only when one gets out of this natural way of life, and gets all excited about the possibility of adding up figures in the monetary realm, that a man runs into trouble.

—“The World Isn’t Finished,”

The Saturday Evening Post, April 23, 1932

Searching for Silence

In what might be the quietest place in the continental United States, I hear only the squeak of boots and water slapping against my hat. I can’t tell if it’s fresh rain or drips from the canopy overhead where old-growth branches lace together and turn the sky spruce-needle green.

Winter storms knocked down trees a hundred feet tall, eight feet in diameter at the base. Already lichen, shelf-fungus, and flowers the size of pinheads punctuate these fallen logs. A dozen kinds of fern twirl around scatters of bark, and soon entire new glades will be springing up. In my acoustically sensitive state, I wonder, what is the sound of leaves stretching very far to find open sunshine?

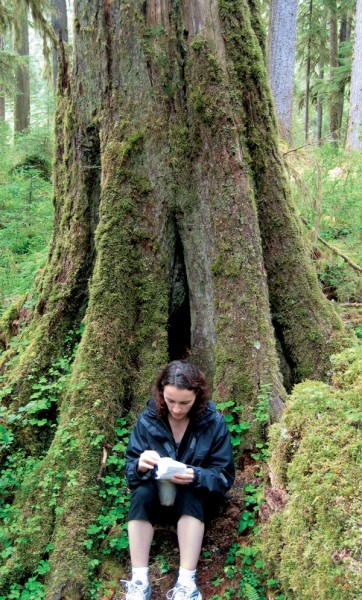

The Hoh Rainforest in Olympic National Park in the northwest corner of Washington state—if Washington is shaped like a mitten, the park’s at the tip of the thumb—is my first stop on a listening tour. I’m hoping that if I pay close enough attention, I’ll learn what the world sounds like when it’s only talking to itself.

I need that, because modern life bludgeons us with sound. Cheap car stereos have more amplification than the Beatles used at Shea Stadium. Thanks to the endless hiss of traffic, 6 a.m. lawnmowers, the clang of construction, that annoying cell phone jangle, we live inside noise. Even when we think we’re in a silent place, we’re not. Tests show that if you ask relaxed people in this country to hum, the note they’ll most likely produce is a B natural—the same as the electricity roaring through the wires everywhere surrounding us.

And in the quietest place in the continental United States, no matter how determined I am not to make a sound, my heartbeat thrums in my ears, almost drowning out the birdsong. I shift my weight, inadvertently bump my walking stick; it falls, clattering against a tree trunk like a wind-up drumming monkey before it finally comes to rest in a patch of moss.

In 1995, Gordon Hempton, an Emmy-winning natural sounds recording artist who was recovering from a bout of temporary deafness and horrified by the noise around him, chose this tiny spot of land in the Hoh Rainforest—47º 51.959N, 123º 52.221W, to be exact—and declared it a sanctuary of quiet. The One Square Inch project was born.

Gordon’s idea is simple, lovely, hopeful: Just as waves ripple out from a dropped pebble in a pond, silence will radiate from a spot that’s kept beautifully still. “One Square Inch is exactly that, an inch I’m defending from noise,” he says at the trailhead, looking over the three of us—me and two young women, a soaking-wet trio of sound pilgrims. “And can one square inch of quiet manage a thousand square miles around it? So far, every indication is that it can.”

Along the three-mile hike in, we stop for slugs, for snails the color of beach sand, for snakes sure they’re doing a remarkable impression of tree roots. The Hoh River, cloudy with glacial silt, parallels us, turning gravity into music, the ever-downhill rush to the ocean.

Then, as we cross a low ridge, the entire soundscape changes. The river drops away, and this tiny valley, Mt. Tom Meadow, seems to hold quiet like a whispering secret. With a meter the size of a paperback book, Gordon checks noise levels. The forest—wind, trees, river, two or three unseen birds calling from the underbrush—comes in at 27 A-weighted decibels (dBA) about half as loud as normal conversation level. Or, to put it more simply, the ringing in my ears is the loudest thing I hear.

We cross under a tree shaped like an upside down wishbone, tramp through mud that grabs at my boots, and then into the deeper forest along an old elk trail. And there, without any fanfare but a tiny marker placed there by Gordon himself, is the Inch.

We scatter, each staking out a bit of territory, each listening eagerly, and just as eagerly hoping to hear very little. What does true silence sound like? At first, there is only the soft noises of the three other people, all boots and Gore-tex, all trying hard not to move, not to breathe loudly, but then the longer I sit, the more I hear. The river rumbles the bass line of the landscape’s music. Birds provide the treble. A woodpecker offers percussion while I watch a translucent spider, no bigger than a match-head, work a triangular fern leaf, and mosquitoes, one of nature’s only drone sounds, zero in on my exposed skin. My breathing stills, my heartbeat slows, and I feel as if I am unfolding, becoming a part of the quietest spot in the United States.

Then the noise comes. “A big fat airplane!” in the disappointed words of a fellow hiker. The plane more than doubled the ambient sound of the Inch, and we reacted to it as a threat: drawing in, tracking the source of the sound, hunching down for cover until the last traces of engine noise finally died away and the landscape’s quiet slowly reasserted itself.

I wonder what we lose when we lose the last bit of country where our sounds—motors and electricity and the unnatural twist of sound through plastic—don’t reach, and we have no respite at all. Surely that would be a failure of national imagination, a blight on that great American dream of room for everything.

Everything, it seems, but the perfect quiet of nature.

When I leave the Inch I think about what I’ve heard in the only place where I’ve ever been that the works of man weren’t always in some way a dominant sound: rain; the river muffled by distance; wind striking notes on trees with leaves, trees with needles, or the dead-end sound of it crashing against one of the giant Sitka spruce trunks. Although the line of sight in the forest is almost nothing—every view is blocked by old-growth—I hear at distances I’m simply not accustomed to, hearing too many things I can’t identify. I’m sure that was an owl a mile or so off, but I can’t begin to name the other half-dozen species of birds that chirped and hooted and harrumphed. We have somehow turned into strictly visual creatures, forgetting that animals define their home by knowing its every sound.

But maybe even worse than the airplane is the simple fact that the entire time I was at the Inch, trying to listen to the world, what I really heard were the noises inside my own head. “When you’re in a really quiet place,” Gordon had said, “it forces you to see who you are.” Apparently who I am is someone whose mind resembles nothing so much as a bunch of clowns at a pie fight, a scene of constant noise and bustle, thoughts spewing like whipped cream.

Maybe my next stop, Rialto Beach, will help. Olympic National Park includes not only the mountainous interior, but also nearly the entire Pacific coastline of the state of Washington, fronting more than 3,000 square miles of open sea. Rialto is, according to Gordon, “the most musical beach in the world,” and the ocean always soothes.

From the Hoh to Rialto is less than 50 miles, but in what seems to be a recurring pattern, I make half a dozen wrong turns and get very lost. Finally, on the western edge of the continent, I am there. In front of me, a line of driftwood, from small branches to entire tree trunks, shields waves from the inland world. The dominant note is a low-pitch hum, almost industrial and constant, like a factory very far off running impossibly large machines. Wave patterns overlay the hum: three small waves followed by a larger wave that comes nearly to where my feet are dug into the sand. Finally, a sound almost too fragile for me to pick up until I’ve sat and listened for more than an hour: the purr of water pulling back over rocks like a particularly delicate wind chime.

“There’s nothing you need to learn about listening,” Gordon had said. “We’re all animals. We all know how. We’re all good listeners when we’re at our most natural.” I think about times when I have been utterly entranced by sound: listening to a musician practice a Bach suite, cello echoing; the roo-roo bark my dog makes when she’s indignant; wind howling across Iceland. And my favorite sound of all, the nearly complete silence of the woman I love sleeping.

“To listen for something is one of the worst things a person can do,” Gordon had continued. “Just open up.” And it’s true; in all of those moments, every highlight of sound I can recall from my past, I wasn’t listening, I was simply there, and that was enough.

A gull flies overhead, low enough that the thump of its wings alone seems strong enough to keep it aloft. Never mind the aerodynamics, flight must have started with this sound, the sheer muscle of wind in feather.

And taking that as a sign of hope, I head to Hurricane Ridge, about 50 miles as the crow flies northeast of Rialto but three times that distance by car. Just past Port Angeles the road turns its back on the ocean and into a different season; from the sea to the ridge the car climbs over 5,000 feet, and the temperature drops 20 degrees.

When at last I get out of the car and walk onto the ridge, a landscape covered with alpine plants only inches tall, the sound is what I hope birds experience, wind unimpeded and on its own errands occasionally deigning to come to earth and lift a raven into the air.

I don’t listen for any of it. I hike to where I see nothing but the bruise blue of distant mountains and simply hear. At least for a little while. Longer than yesterday. Longer than the day before. And that’s a hopeful thing because what the world is telling me in these sounds is that any time I remember to pay attention it will be there, singing to itself and to anybody else who wants to listen.

SHHH! 5 More of America’s Loveliest Noise-Free Zones

Olympic National Park’s Hoh Rainforest, site of Gordon Hempton’s One Square Inch project (onesquareinch.org), may be the quietest place in the Lower 48, but if you care to plunge into a silent spot or a place where only nature makes noise, here are five other wonderful places to visit:

1. Cape Cod is known as home to the rich and famous, but it still has some spots of nearly untouched wilderness. Marconi Beach (just below Wellfleet) is “amazingly quiet—you wouldn’t figure,” says Hempton. Show up just before sunrise.

2. Voyageurs National Park lies along Minnesota’s border with Canada. Hempton calls it “sonically inspiring, surprisingly quiet.” Voyageurs’ prime listening attraction is Lake Astrid. On a summer evening, sit back and enjoy that quintessential sound of the north: the loon’s warbling cry.

3. The Everglades are full of wildlife, but the landscape is threatened because of water depletion, and the soundscape is under attack by airline overflights. Hempton suggests spending a night at Big Cypress for a sonic environment of songbirds and the increasingly rare growl of frogs.

4. Hawaii Volcanoes National Park on the Big Island is technically the quietest spot in the United States; inside some of the volcanic cones, researchers have gotten sound readings at a fraction of that of human breath. However, the park is also one of the nation’s most popular for air tours. Bad weather is the key; low clouds keep the helicopters grounded, and a hike into one of the volcanoes will likely be near silent.

5. The Grand Canyon, like Hawaii Volcanoes, is under tremendous sonic threat from air tours, but the National Park Service maintains a no-fly zone over the rim-to-rim trail. For drivers, the North Rim is less frantic than the South; for hikers, stay overnight at Havasupai Falls on the canyon’s bottom then head into the box canyons nearby (some registering as low as 3 dBA). Mike Buchheit, director of the Grand Canyon Field Institute, says the best time for silence-seekers to come is in January or February when fresh snowfall muffles the soundscape. He adds, “The canyon wren is the sound of the backcountry here. It’s your ticket to heaven.”