The Post Story That Changed Baseball

When James Thurber wrote “You Could Look It Up” for the Post in 1941, he probably thought of it as merely a short story — a distraction from the sobering realities of a world at war. His work certainly achieved that goal (who wouldn’t be entertained by the story of a cigar smoking, beer drinking, trash-talking dwarf on a big league baseball team?)

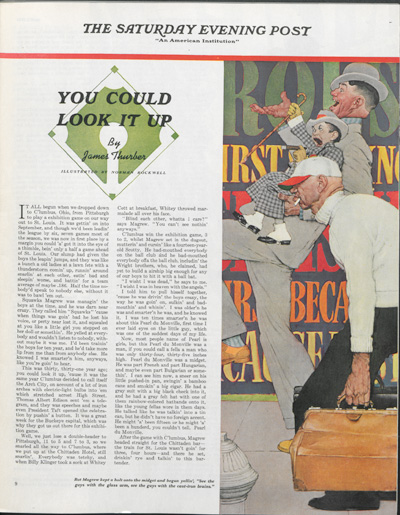

But his story (illustrated by Norman Rockwell) might have achieved more: it probably inspired one of the most bizarre events in the history of baseball, and in doing so forever changed the rules of the game and the record books.

In 1951, St. Louis Browns owner Bill Veeck signed 3’7” Eddie Gaedel as an amateur free agent. The little person appeared for only one at bat, and, despite catcher Bob Swift’s futile advice for his pitcher to “keep it low,” was walked in four throws. Gaedel was replaced by a pinch runner and received a standing ovation as he returned to the dugout.

The gimmick permanently changed baseball, as it created the rule that nobody can appear in a game until the commissioner approves his contract. Gaedel also holds two Major League records that will probably never be broken: one for being the shortest player ever, the other for the highest on-base percentage (1.000).

Veeck never admitted that the Post story inspired his publicity stunt, but it’s hard to believe it was just a coincidence.

Click here to read “You Could Look It Up”

Reveling in the Past of America’s Favorite Pastime

When Major League Baseball’s All Stars take the field in July at Busch Stadium in St. Louis, thousands of fans will be thinking of Mel Ott and Eddie Joost instead of Derek Jeter and Albert Pujols. They’re keepers of the flame for teams alive only in sports history books and their own memories.

The New York Giants, Washington Senators, Boston Braves, St. Louis Browns—thousands of diamond enthusiasts still hold allegiance to these bygone teams. They organize fan clubs, celebrate great moments at meetings, and swap items on eBay every day all in the name of honoring the past of America’s pastime.

And their own youths.

Ron Gabriel grew up two miles from Ebbets Field, home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, at a time when you could hear radio announcer “Red” Barber’s play-by-play “from every open window in Brooklyn,” he recalls. These days Gabriel lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland, but Brooklyn never quite left the boy. On October 4, 1975, at 3:44 p.m., he formed the Brooklyn Dodgers Fan Club. It was 20 years to the minute of the team’s first and only World Series victory.

“I realized this intensity needed someone to bring [Dodgers fans] all together, to kind of act as a clearinghouse. I was confident I could do that.”

Gabriel hosted annual meetings at his home (serving hot dogs and Schaefer Beer, a longtime Dodgers’ sponsor). When the 50th anniversary of the team’s World Series victory rolled around in 2005, he organized a commemorative dinner and passed out bumper stickers: We Loved the Brooklyn Dodgers — and we still do!!

But for Gabriel and thousands of fans of Dem Bums, the world changed when the team moved to Los Angeles beginning with the 1958 season. “I went into a state of shock,

and I still am, still can’t believe it.” Diehards were devastated and many, like Gabriel, never transferred their allegiance to another team. “Once a Brooklyn fan, always a Brooklyn fan,” he says.

There is a common thread that binds fans of defunct teams, a certain poetry in their recollections that are valentines to the boys of summers past. You can hear it in the way they share stories —always in the present tense. Bobby Thompson hits the “shot heard round the world,” Willie Mays makes his magical over-the-shoulder catch. With each retelling, there are new insights, a deeper understanding. The drama of the game continues to unfold. Instant replays, never distant replays.

“We’re in the Twilight Zone,” says Bill Kent, founder of the New York Baseball Giants Nostalgia Society. “To us, the old Giants are still alive. We relive their exploits.”

Kent grew up in the Bronx, a trolley and subway ride away from the old Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan. As a youngster, Kent would sometimes sneak into the ballpark by climbing over the fence before crews arrived and stake out empty seats with his friends. Other times, he’d get picked to turn the turnstiles at the entrance gate, earning spare change and free admission to the game. It was a highly coveted role. “There were always more kids than jobs.”

The Giants society is a loosely knit group of baseball fans, lawyers, teachers, sports writers, and even “a lady umpire and a lady baseball player” among them, who participate in an online discussion group and get together three times a year for what Kent calls schmoozing. Three or four people showed up at the first meeting held at a Chinese restaurant. Word spread, and Kent had to find larger quarters at an Italian restaurant. These days, meetings attract upwards of 50 and are often held in a church basement. Ten dollars pays for the pizza. There are even a couple of Dodgers fans and a sprinkling of Mets fans. “We don’t care. We have nice people, and if they’re not nice, they’re out,” he says.

The 1950s was a turbulent decade for baseball fans. In 1953, the St. Louis Browns played their last game at Sportsman’s Park before moving to Baltimore. Brownies pitcher Ned Garver, who won 20 games for the 1951 team that ended with a 52-102 record, once famously said: “Our fans never booed us. They wouldn’t dare. We outnumbered ’em.” At least their legacy is alive and well. The St. Louis Browns Historical Society and Fan Club is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year.

In 1954, the Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City; in 1953 the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee. And, of course, there was the twin sting for New Yorkers in 1958 when both the Dodgers and Giants made their way to California.

When the Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City starting with the 1955 season, it wasn’t a surprise. But that didn’t make it any easier for fans like Dave Jordan. “For a couple of years it was clear the A’s were running out of money,” he says. The city couldn’t support both the A’s and the Philadelphia Phillies. Still, Jordan says when the mayor announced a “Save the A’s” committee, “I was one of few people who took him seriously.”

Jordan is chairman of the board of the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society in Hatboro, Pennsylvania, a robust organization of 800 members spread coast to coast. The society puts out a bimonthly newsletter, runs a museum, and holds functions to which original players are invited. There are a few younger members, but Jordan says that for the most part, its ranks are filled with people who were Shibe Park regulars in the days of Lefty Grove, Jimmie Foxx, Eddie Collins, and Mickey Cochrane. One of Jordan’s favorite ballpark memories was the 24-inning game against the Detroit Tigers on July 21, 1945, called due to darkness.

“I kept score for 22 innings until I ran out of space.” He donated that incomplete scorecard to the Philadelphia A’s Society Museum and Library.

When the team moved on to Kansas City, Jordan stayed a fan. “In 1955 and 1956 I went to Yankee Stadium when Kansas City was in town, but it wasn’t the same. They changed the numbers of quite a few players, and eventually I had to face the fact that the Phillies were what we had left.”

Middle-aged fans are now golden agers and elder statesmen. “That’s something we at the society think about,” Jordan says. “Until recently, we always had a big breakfast in the fall, selling out with hundreds of fans showing up.” But, he says, as volunteers get older, functions are being scaled back.

There are also fewer players alive who wore the uniform.

The repercussions are showing up in the sports memorabilia market. Mike Heffner, president of Lelands.com, the oldest and one of the largest sports memorabilia auction houses, says the 1980s and ’90s were the boom days in memorabilia of defunct teams. “In the past few years, we’ve noticed a slowdown. People who were following teams in the 1940s and ’50s are mostly retired, some have passed away, and their collections have been sold.”

Some team items are valuable not because of the passion of their fans but because of their scarcity. The Seattle Pilots, for instance, played one year in 1969 before becoming the Milwaukee Brewers. “They didn’t have a huge fan base. There aren’t a tremendous

amount of them out there. But a uniform patch or a team-signed ball is very rare, so it’s tremendously collectible,” Heffner says. The Colt .45s (1962-1964), a squad that became the Astros, “were a terrible team, but they had really neat uniforms with a pistol on the front, so they’re highly collectible.” The latest franchise to join the brotherhood of bygone teams is the Montreal Expos, now the Washington Nationals. But don’t look for big returns there. “Canada and baseball don’t go together that well,” Heffner says.

Of course, for fans it’s not about money and not even about memorabilia. Their teams may not be in the box scores, and the ballparks may long be gone, but the boys of summer never grow old.