The A-Rod Factor: Cheating in America’s Favorite Pastime

No one set out to make baseball the great national metaphor. It was just a game that involved a bat and a ball, played under a variety of rules and names, like “rounders,” “base,” or even “four-old-cat.” By 1828, it was being called “baseball” in newspapers, and by the 1840s there were league games in New England. It was played up to, and through, the Civil War. With the fighting ended, men who had learned the game while in uniform took it home with them, and its popularity grew throughout the states.

The growth of baseball was a welcome sign after the war. Americans yearned for indications that the nation was reuniting. They were encouraged by the growing number of baseball clubs, playing with roughly the same rules, that sprang up in both northern and southern states.

Even before the war, the U.S. had relatively few traditions and symbols that were valued in all states. Americans noted how European nations were united by common ancestries and ancient histories when their own country, in contrast, had an immigrant population that seemed to lack a distinctive character. And their national heritage was based on just one century of history.

Many of these same Americans looking for a national symbol thought it could be found in baseball. It seemed to reflect the principals of life in America–tough, but fair. It offered the boys and men (and sometimes ladies) who played the game a sense of achievement, cooperation, and friendly competition. And it was fun.

In 1902, the Post editors—clearly great fans of the game—were inspired to rhapsodize on the glories of baseball. “It is a manly game,” they said. And it was “a clean game. With a single exception, professional baseball has never been found to be dishonest.”

That single exception, they wrote, occurred in 1877, when players in the National League were “found guilty of throwing games.” They were expelled and have never since been permitted to play in or against a regularly organized team.” (They might have been referring to two St. Louis players, who gamblers had identified as their accomplices in a racket of throwing games.)

“The expulsion of the players above referred to took place,” the editorial continued, “and, with this, gambling became almost unknown in connection with baseball.”

“There is no use in blinking at the fact that at that time the game was thought, by solid, respectable people, to be only one degree above grand larceny, arson and mayhem, and those who engaged in it were beneath the notice of decent society.”

Source: Library of Congress

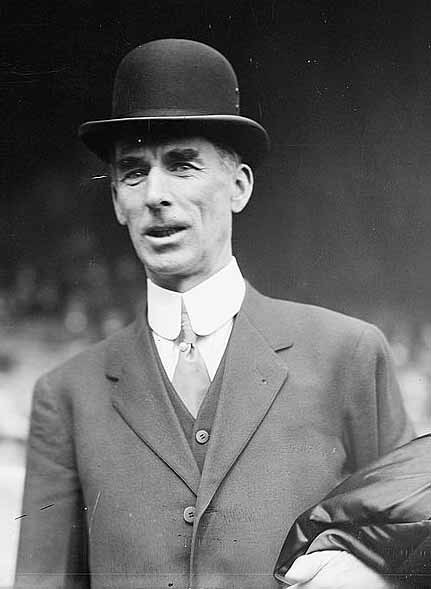

So said the Post’s editors. But that’s not the way Cornelius McGillicuddy heard it. The man who later became known as Connie Mack, the widely respected manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, started his career as a ball player in Connecticut. And this is how he remembered that ‘clean’ game:

“There is no use in blinking at the fact that at that time the game was thought, by solid, respectable people, to be only one degree above grand larceny, arson and mayhem, and those who engaged in it were beneath the notice of decent society.

The late A. G. Spalding estimated that about 5 per cent of the players were crooks in the early days of professional ball. To quote Spalding: ‘Not an important game was played on any grounds where pools on the game were not sold. A few players became so corrupt that nobody could be certain whether the issue of any game in which they participated would be determined on its merits.’

Liquor selling, either on the grounds or in close proximity thereto, was so general as to make scenes of drunkenness and riot everyday occurrences, not only among spectators but now and then among the players themselves. Almost every team had its ‘gushers,’ and a game whose spectators consisted for the most part of gamblers, rowdies, and their natural associates could not attract honest men or decent women to its exhibitions.”

All this was unknown, forgotten, or ignored by the Post’s editors in the 1900s. In a 1908 editorial, for example, they broadly claimed that baseball represented the highest ideals of the nation—“our one, perfect institution.” It was “above reproach and beyond criticism…one comparatively perfect flower of our sadly defective civilization—the only important institution, so far as we remember, which the United States regards with a practically universal, critical, unadulterated affection.”

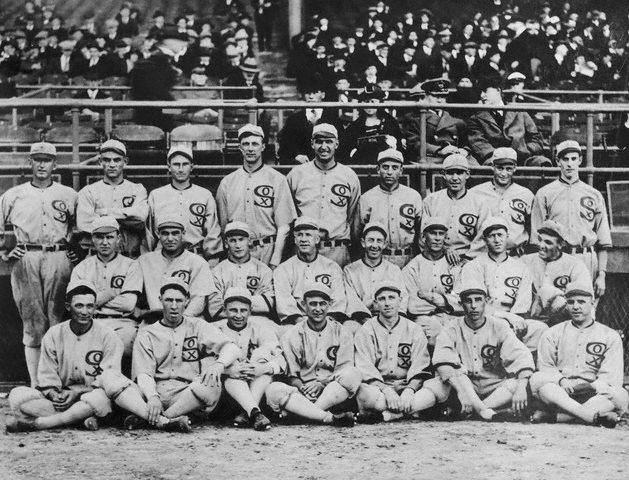

But just more than a decade later, the country learned that several players on the Chicago White Sox roster had conspired with gamblers to throw the World Series. The nation was stunned. Baseball fans might claim that players or umpires were throwing a game; it was the birthright of anyone who supported a losing team. But news of an actual conspiracy, by several players, to throw not just one game but the World Series, was outrageous.

Recalling those times in 1938, sports writer John Lardner wrote in the Post, “It nearly wrecked baseball for all eternity… It touched off a rash of scandal rumors that spread across the face of the game like measles. A hundred players and half a dozen ball clubs were involved in stories of sister plots. Baseball was said to be crooked as sin from top to bottom.

And people didn’t take their baseball lightly in those days. They threw themselves wholeheartedly into the game when World War I ended, so much so that the sudden pull-up, the revelation of crookedness, was a real and ugly shock. It got under their skins. You heard of no lynchings, but Buck Herzog, the old Giant infielder, on an exhibition tour of the West in the late Fall of 1920, was slashed with a knife by an unidentified fan who yelled: “That’s for you, you crooked such-and-such.” Buck’s name had been mentioned by error in a newspaper rumor of a minor unpleasantness in New York…[He was] as innocent as a newborn pigeon, but rumors were rumors, and the national temper was high.

It’s a fact that some of the White Sox, after the scandal hearings, were unwilling to leave the courtroom for fear of mobs.

That anger at the game’s betrayal was seen recently when a ballplayer was charged with long-time abuse of performance-enhancing drugs. Some fans were outraged, and called for brutal punishment of the offender. Other fans merely shrugged their shoulders and accepted the fact that cheating was an ineradicable part of the game.

Corruption will always be a possible factor in the game. Even the Post’s 1902 editorial, while praising the purity of the game, recognized “the instant a sport reaches the professional stage it is beset by temptations which appeal to avarice, and must then begin a constant struggle to preserve its integrity and true sporting spirit.”

The struggle continues, with the suspension of Alex Rodriguez today and, no doubt, with future investigations, scandals, and penalties in the future. There will always be people looking to cheat at professional baseball, enriching themselves and impoverishing the game. And there will always be officials and players who work at stopping them and protecting the value of the game. It is this endless contest of corruption and restoration that makes professional baseball a true symbol of the United States.