Hey NCAA, Nix Those Backboards!

Ski Weld

January 24, 1942

Every sport has fans who think their game has gone sharply downhill over time. Baseball, football, hockey, even horse racing — whatever their game, they’ll tell you it used to be a lot better. In the old days, the sport was a contest of skill, they’ll say, not luck or brute force. Athletes in those idyllic days were faster, smarter, or nobler. (Sports, of course, aren’t the only things that have degenerated over time. The same is said about movies, restaurants, rock music, gas stations, Cracker Jack prizes, and — while we’re on the subject — people in general.)

But even in the Good Old Days, there were purists who looked further back to the Even Better Old Days.

In 1940 Stanley Frank, for example, complained in The Saturday Evening Post that college basketball was no longer played with skill or intelligence: “The big idea is to barge down the court in harum-scarum fashion, let someone unload a wild shot and, if it fails, have one of those 6-foot, 6-inch human skyscrapers — standard equipment for every top-notch team —… grab the rebound and dunk the ball through the hoop.”

To see how the game should be played, he wrote, you needed to look back 14 years. Back in 1926, basketball was a game of skill. In those days, college teams rarely scored more than 20 points. Now, he sputtered, Long Island U was averaging 55 points a game. Fans couldn’t even keep a box score for a basketball game anymore. While jotting down the last point scored, you’d probably miss another basket. “Comment to your neighbor on a good play [and] one of the athletes will bring down the house behind your back with a more stirring piece of heroics.”

Basketball was becoming too intense, Frank griped on. When Centenary College defeated Loyola of New Orleans, 78 to 72, “the sight and sound of so much furious activity were too much for two customers. They fainted dead away.”

This feverish pace of scoring had to be stopped before the game was ruined. Fortunately, the coach of Columbia University had an idea how it could be done: Take away the backboards.

“Make the players shoot at open baskets as the old professionals did, and you’ll see science and skill replacing sheer luck and height as the most important factors in the game,” said Coach Paul Mooney. “You won’t see kids so ready to pitch wild, screwy shots off one ear, as they do now, if they know the backboard isn’t there to stop the ball from going out of bounds.”

The backboard wasn’t originally meant to play a role in scoring. When Dr. James Naismith invented the game 120 years ago, he simply nailed a peach basket to the edge of a gymnasium balcony. A backboard made of chicken wire was only added to prevent balcony spectators from reaching down and blocking shots. When players saw how easily the wire mesh bent, wooden backboards were introduced. Players soon realized they could bank shots off the solid backboard. Later, fans sitting behind the backboards at Indiana University complained that it blocked their view, and the glass backboard was introduced.

The game had been continually evolving since it was introduced. Nearly every aspect of the sport’s equipment and regulations had been altered since its invention in 1891. And not all fans agreed that the changes had resulted in a better game.

Stanley Frank had several criticisms of 1940 basketball, but he believed removing the backboards would help return basketball to its former glory. Scores would drop to pre-1940 levels, and the game would lose its annoyingly frantic pace. It would be, once again, a game of skill.

What he didn’t recognize is that skill alone probably wouldn’t draw immense crowds to college basketball games. Watchmaking is a skill, but no one’s ever sold tickets to see it.

A Hasty Prediction For the G.I. Bill

Its official name, when passed by Congress in June of 1944, was the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act, but it was soon renamed “the G.I. Bill of Rights.” While it provided several benefits to the veterans returning from World War II, the best remembered was the Reserve Education Assistance Program. Stanley Frank described the benefit in an August 18 issue of the Post:

Any man who has served in the armed forces for ninety days can attend for a year any approved school or college, and if he was less than twenty-five years of age at induction he is entitled to these benefits for a period equal to his military service after September 16, 1940, for a maximum of four years. The Government pays all bills for tuition and fees up to $500 a year.

It is a splendid bill, a wonderful bill, with only one conspicuous drawback. The guys aren’t buying it. They say “education” means “books,” any way you slice it, and that’s for somebody else. [“The G.I.’s Reject Education,” Stanley Frank, August 18, 1945]

He was right—partially, and only briefly.

As of February 1, 1945, only 12,844 discharged veterans throughout the country, in a total of 1,500,000, were attending schools under the G. I. Bill. Less than 1 per cent.

Frank had interviewed G.I.s at two veterans hospitals and found them anxious to get home and back to work as quickly as possible. Only 10% showed interest in further education. Most of these soon dropped out of the program.

Boiling down the figures, about 2 per cent of the amputees and neurosurgical cases—those who need it most—indicate an intention of having a go at serious, brain-building learning.

United States Army statistics prove that though [public education] has been free it hasn’t been popular. Only 23.3 per cent of the troops finished high school, and 3.6 per cent are college graduates. The average American soldier left school in the tenth grade, but … there are 5,000,000 in the armed forces who failed to graduate from grammar school.

Frank suggested the problem wasn’t schools, but “unchanging human nature”—i.e., most men don’t want to plan very far ahead in life.

We are, perhaps expecting too much of the tired, bewildered, embittered soldier, disassociated as he has been from civilian life, in asking him to plan his career. In normal times, most people have modest ambitions and are content to drift with the tide, evading responsibility if they can.

Though the college-benefit program had been in effect for a short time, some Post editor already saw the education benefit as a giant waste of taxpayer’s money.

Yet, by early the next year, there were signs of a general shift in Americans’ attitude toward education. Civilian adults, like the returning veterans, wanted to make up for the opportunities they’d lost during the war, and the Depression before it. Early in 1946, the Post reported “facilities of the country’s adult-education program are creaking under the load as [Americans] enroll by the hundreds of thousands.”

If, citizens have reasoned, a university can help practicing physicians, engineers, and so on, keep up to date, why can’t it tackle things that have ordinary folks stopped in their tracks?

A Gallup poll last spring indicated that 34 per cent of the adult population—25,000,000 folks—had the impulse to take advantage of part-time educational facilities after the war. [“Look Who’s Going To School Now!” Harold Titus, Feb. 9, 1946]

And just one year after the Post reported G.I.’s rejected education, it ran “Crisis at the Colleges.”

Heads of American colleges … are confronted with a reality that has always been a democratic dream: the opportunity to raise the educational attainments of a solid chunk of a whole generation. Because of the Government subsidy to servicemen, the opportunity is here; men who could never come to college under ordinary circumstances are enrolling or knocking at the doors.

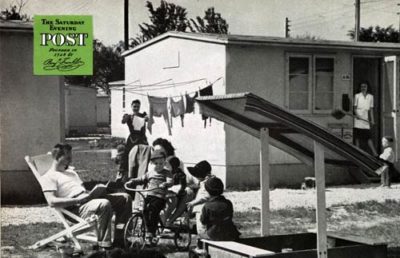

[However] the colleges do not have the facilities, the housing, the instructors, or classrooms to handle [the opportunity]. The primary, the immediate, the all-important, problem is housing.

Thousands of eligible veterans were turned away last September because the colleges had no place to quarter them; thousands more were turned away in February at the beginning of the second semester. And yet the enrollment of veterans rose immensely because the colleges did find some place, some way, to house some of them.

Here was the situation at Illinois during the second half of the school year. Total undergraduate enrollment at Urbana … was 12,780. This is more students than ever attended there before. … Total veteran undergraduate enrollment was 5509.

There were veterans living in basements, veterans in garrets, veterans in made-over garages and abandoned filling stations. There were 300 sleeping in double-decker beds in the gaunt building known as the Old Gymnasium Annex.

Gone is the campus where every prospect pleases… Cruelest blows to academic serenity are the clotheslines behind the trailers and prefabricated houses. Along with the leaves of the traditional whispering maples there are, diapers and children’s underpants blowing in the wind.

By the time the program ended in 1956, it had helped 2.2 million Americans attend college and another 6.6 million receive training.

It would be hard to over-estimate the effect on this country made by this wave of America’s college-educated G.I.s. It enabled these men to lead the changing industries of the post-war world. It also produced a higher expectation for education in the American public; a 10th-grade education became less socially acceptable in the growing middle class.

The G.I.-Bill generation passed its faith in education on to the next generation, which passed on to their children. It is still an article of faith to many Americans today despite the low employment rate of college graduates.