8 Things You Don’t Know about “The Star-Spangled Banner”

How and why Francis Scott Key wrote the poem that would eventually become our national anthem is a well-known American legend. What is less known is that the journey from poem to anthem was long — more than a century — and fraught with controversy. Here are eight things that might surprise you about “The Star-Spangled Banner” and its divisive history:

1. Francis Scott Key did not compose “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

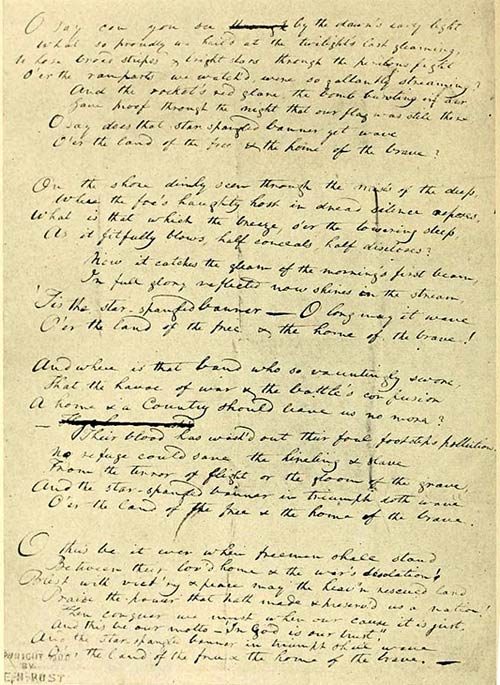

On a list of the country’s greatest composers, you’ll find familiar names like Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and George Gershwin. Francis Scott Key will not — and should not — appear on that list. He was a lawyer and an amateur poet who, on September 14, 1814, wrote a poem called “The Defence of Fort M’Henry” while aboard a British ship during the night-long bombardment of Fort McHenry, Baltimore. Though you might say he “composed” the poem in a broad sense, he was not what is considered “a composer.” Some historians even believe he was tone deaf.

2. The tune for the national anthem is a British song about sex and drinking.

The Anacreontic Society was a gentlemen’s club of amateur musicians founded in 18th-century London and named for Anacreon, a 6th century B.C. Greek poet. Sometime in the late 1760s or early 1770s, John Stafford Smith wrote music to accompany words written by Society President Ralph Tomlinson. The result was “The Anacreontic Song,” or “To Anacreon in Heaven,” and its lyrics were no staid bastion of propriety. It ends like this (starting where “And the rockets’ red glare” is sung in the national anthem):

Voice, fiddle, and flute, no longer be mute,

I’ll lend you my name and inspire you to boot

And besides I’ll instruct you like me to entwine

The myrtle of Venus with Bacchus’s vine.

Venus is the Greek goddess of love and sex, and Bacchus the god of wine. This last line is an invitation to get drunk and naughty.

Stafford’s tune was often appropriated for patriotic songs, and Francis Scott Key would have been familiar with it. It’s likely he intentionally fit the words of his “Defence of Fort M’Henry” to the tune of “The Anacreontic Song.” It quickly became the standard tune to which Key’s poem was sung, and it is now the national anthem of the United States.

3. The first word of “The Star-Spangled Banner” is not “Oh.”

Used almost exclusively in verse, the real first word of “The Star-Spangled Banner” — O — is, according to linguist Arika Okrent, a vocative O. “It indicates that someone or something is being directly addressed,” she writes, comparing it to a number of other well-known Os, including “O captain, my captain,” “O ye of little faith,” and “O Christmas tree.”

“Oh has a wider range,” she continues. “It can indicate pain, surprise, disappointment, or really any emotional state.”

And yes, it appears again in the penultimate line of the anthem: “O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave …”

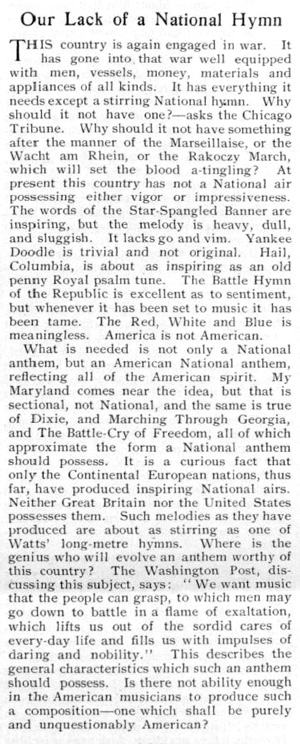

4. Many people opposed “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the national anthem.

It seems there were many reasons to dislike “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Music teachers and professional vocalists complained that the range of the song made it difficult to sing and to teach. Pacifists believed it was too violent in tone, a glorification of war. Nationalists didn’t like that the tune was of British origin. And Prohibitionists protested that our national anthem shouldn’t be what is essentially a drinking song. Other songs that were considered anthem-worthy were “America the Beautiful,” “Hail Columbia” (now the ceremonial march for the vice president), and even “Yankee Doodle Dandy.”

5. The original poem had four verses and specifically mentioned slavery.

Thankfully, we don’t sing all four verses of Key’s original poem. Not only would that stretch the pregame anthem to more than six minutes, but the third verse would be a constant source of controversy. It contains the lines

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave

During the War of 1812, hirelings were black slaves hired to fight for the British military on the promise of freedom should they survive the war. Slaves and hirelings are the only people singled out for death or defeat in the poem.

Francis Scott Key, a slaveholder himself, certainly didn’t extend his vision of “the land of the free and the home of the brave” to people of color. As Jefferson Morley reports in his book about the race riots of 1835, Snow-Storm in August, Key was known to have publicly spoken about African Americans as “a distinct and inferior race of people, which all experience proves to be the greatest evil that afflicts a community.”

6. A fifth verse appeared 47 years later.

In 1861, as the Civil War was spreading across the young country, American poet Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (father of the future Supreme Court justice) penned a fifth verse that spread widely in the north but eventually faded from the public consciousness. It, too, mentions slavery, but welcomes the “millions unchain’d” to “the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

When our land is illum’d with Liberty’s smile,

If a foe from within strike a blow at her glory,

Down, down, with the traitor that dares to defile

The flag of her stars and the page of her story!

By the millions unchain’d who our birthright have gained

We will keep her bright blazon forever unstained!

And the Star-Spangled Banner in triumph shall wave

While the land of the free is the home of the brave.

According to the Library of Congress, the significance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” was not lost on the Confederacy during the Civil War: Songs with names like “Farewell to the Star-Spangled Banner” and “Adieu to the Star-Spangled Banner Forever” — clearly a reference to Key’s song — were published and sung all around the South.

7. The U.S. had no official national anthem during World War I or the first eight Summer Olympic Games.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” found its first official use in 1889, when Secretary of the Navy Benjamin F. Tracy directed that it be the official tune to accompany the raising of the flag by the Navy. In 1916, the year before the U.S. entered World War I, President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order stating that “The Star-Spangled Banner” should be played whenever the performance of a national anthem was appropriate.

Not until 1930 did a congressional bill to establish a national anthem find any traction. In that year, Maryland Representative John Linthicum (D) introduced a bill to make “The Star-Spangled Banner” the national anthem. President Herbert Hoover signed it into law on March 3, 1931, almost 117 years after the poem was first penned. March 3 is still celebrated as National Anthem Day in the U.S.

8. There’s still plenty of opposition to “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In July of 1976 — shortly after Independence Day in America’s bicentennial year — Texas Representative James Collins (R) introduced a bill to the House of Representatives to change the national anthem to “God Bless America.” Indiana Representative Andrew Jacobs Jr. (D) introduced not one but six separate bills to change the national anthem, one bill for each term he served between 1985 and 1996. His choice for anthem was “America the Beautiful” because not only is it easier to sing, but it also is more representative — the music was written by Samuel Augustus Ward and the words by Katharine Lee Bates, a man and a woman, both Americans.

More recently, Senator Tom Harkin (D) of Iowa took up the cause. At the end of 2014, he introduced a bill to the Senate to replace the national anthem, again with “America the Beautiful” because it “far better represents the scope and majesty of the geography of the United States of America as well as the principles of freedom, liberty, fraternity, and progress that are the unifying beliefs of our democracy.”

In each case, the bill was referred to a committee and never heard from again.