6 Myths about the Stock Market Crash of 1929

The great stock market crash of October 29, 1929, was so unbelievable and so excessive that is inspired several enduring myths. Here are 6 commonly held beliefs about the great crash that turn out to be more legend than fact.

1. The Crash Came Out of Nowhere

One of those myths claims the Crash was totally unexpected. Admittedly, it was dramatic reversal of economic trends. America had experienced 30 years of continual economic growth. While some believed — or wanted to believe — that the stock market would continue to rise, business leaders knew a correction was coming. Sooner or later, the market would come to its senses and stock prices fall back down to reality.

Yet stocks continued to soar, nearly doubling in a year.

One factor that drove up prices was the easy credit that banks extended to investors. They could now buy on “margin,” which meant they paid only part of the stock price. Their banks provided the remaining amount. The difference (“margin”) would be repaid out of the stock’s anticipated earnings.

But if stock started losing money, the bank would sell the stock and the buyer have to repay the bank what they put up for the margin.

2. Everyone Invested in the Market

This leads to another legend: that a broad cross-section of Americans — farmers, school teachers, factory workers — invested in the market. Supposedly, nearly everyone was in the stock market prior to the crash. One historian asserted that as many as 20 million Americans were buying securities. But according to the Treasury Department’s calculations, the number was actually three million. And brokerage houses reported it was half that number by 1929, which means that over 97 percent of America watched the stock market crash from the sidelines, according to Freedom From Fear by David M. Kennedy.

3. The Stock Market Collapsed in One Day

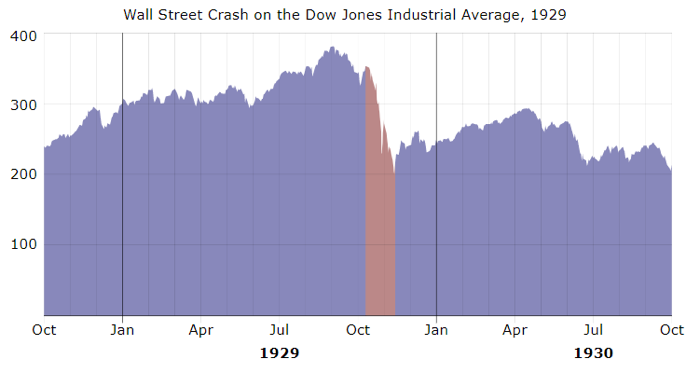

The first sign of trouble was a mysterious drop in prices in September, but it quickly reversed itself, again without reason. All was peaceful until October 23, when the market received a flood of sell orders. By the end of the day’s trading, six million shares had been sold, mostly at a loss. Four billion dollars in stock value was lost.

The slide continued on Black Thursday. Nearly 13 million shares were traded, and the loss in stock value amounted to $9 billion. Panicking investors took some encouragement by a surge of buying at the end of the day. By closing, market values had recovered about a third of what had been lost on Wednesday.

Business leaders urged investors to remain calm and ride out the storm. The market, they said, could still recover from this “correction.”

The market on Saturday’s half-day of trading showed no losses on the scale of the previous three days. But on Monday morning the slide returned. The price of a share might drop anywhere between two and ten points between sales.

And then came Black Tuesday.

The very first item reported on the ticker that morning was the price of Anaconda Copper. It had traded at 96 the day before. At 9:00 AM, it was already down to 80. Investors began frantically selling, driving down the price of stocks sharply.

Within the first half hour 3.2 million shares had been traded. AT&T fell from 310 to 204, RCA fell 110 to 26.

By noon, 8 million shares had been sold.

In the afternoon, prices seemed to level off. Anaconda was now selling for $10 a share. Bank stocks fell, too; National City Bank dropped from 450 to 320.

When trading ending, 30 leading industrial stocks had lost 40 percent of their September value.

According to William Klingaman’s 1929: The Year of the Great Crash, total losses since the previous Wednesday were $15 billion.

Traders who had been wiped out wandered aimlessly though hotel lobbies and down the streets crowded with 10,000 people, drawn to the Wall Street area by reports of the crash.

Harpo Marx, who’d sunk his fortune in Wall Street, received a telegram from his broker. “Send $10,000 in 24 hours or face financial ruin.” But Harpo was already ruined, having sent the last of his money to cover previous margin calls. He was left, he said, with only his harp and his croquet set.

Klingaman notes in his book that composer Irving Berlin admitted, “I was scared. I had had all the money I wanted for the rest of my life. Then all of a sudden, I didn’t. I had taken it easy and gone soft and wasn’t too certain I could get going again.”

The market continued to fall for the next three weeks.

4. Many Stockbrokers Jumped from Buildings

The most colorful legend of the Crash is that of the plummeting millionaires.

Winston Churchill was staying at the Savoy-Plaza Hotel in New York the day after Black Tuesday. That morning, he looked out his window at a crowd forming in the street, staring, he learned, at a man who’d thrown himself down fifteen stories. Somewhat flippantly, he said, “quite a number of persons seem to have overbalanced themselves by accident in the same sort of way.”

In fact, there were no reports of ruined businessmen hurling themselves from skyscrapers that day. Moreover, as economist John Kenneth Galbraith discovered, the suicide rate for October and November of 1929 actually dropped.

Klingaman notes that the crash did result in some fatalities, though, like the man watching the stock ticker in his broker’s office who dropped dead. Or the investor in Kansas City who shot himself in the chest. Before dying, he said, “Tell the boys I can’t pay them what I owe them.”

There are three reports of jumpers in New York city. One was a woman working in a brokerage who’d been processing sales figures to a point beyond exhaustion. She jumped from the 40 story Equitable Building on November 7. Nine days later, a member of the New York Mercantile Exchange leapt to his death. The third jumper was an executive for the Earl Radio Corporation who’d lost his fortune and was now $23,000 in debt — but this had occurred weeks before the crash.

5. The Stock Market Crash Started the Great Depression

It seems to make sense; Wall Street fortunes are wiped out and the economy falls into a long decline. Yet economists can find no direct connection between the Great Crash and the Great Slump. A business slowdown had been noted in the summer of 1929, but it was nothing extraordinary. Even after reports of the Crash circulated, American business seemed unaffected. The day after Black Thursday, President Herbert Hoover made a statement that would haunt him for the rest of his days: “the fundamental business of the country, that is production and distribution of commodities, is on a sound and prosperous basis.” However, according to Kennedy’s Freedom From Fear, it was probably an accurate description of the American economy at that moment.

6. The Government Just Sat Back and Watched the Market Fall

Lost amid all the tragic legends of the Crash is the story of a nearly forgotten hero. George L. Harrison, governor of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, made a proposal to several of the bank’s board members. Consequently, he announced, before trading began on Tuesday, October 30, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York would purchase $100 million in government securities, according to Maury Klein in Rainbow’s End: The Crash of 1929.

The purchase brought badly needed money into the market. It was, according to business historian Maury Klein, “the pivotal moment of the crash. By making these funds available to banks for lending during the severe credit crunch, he probably saved many individuals and institutions from failing. No single act did more to stave off even worse disaster on this disastrous day.”

Featured image: Alamy

North Country Girl: Chapter 48 — The Accidental Model

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

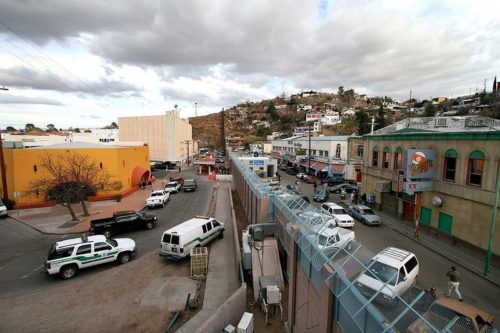

James and I were on our way back to Mexico, driving his El Dorado from Chicago to Acapulco, probably the only time a Cadillac has been used as economy transport. After escaping from the police in Dallas, it was a relief to finally see the signs telling us the Mexican border was near — no more Texas! At the border crossing we were greeted with no more than the usual stares at the sight of a forty-three-year-old man and a twenty-one-year-old blonde in a new El Dorado covered in a layer of Texas dust; border patrol officials on both sides spent more time looking at us than at our passports.

As soon as we crossed the border, James, who had driven though most of Texas, pulled to the side of the road, slumped over, and mumbled that he had to get some sleep. We switched seats, I took over the wheel, and I drove into bedlam. Gone were the smooth, well-maintained US highways. I had to swerve into the other lane or the shoulder to avoid potholes that would have swallowed up the Caddy. There were also: long stretches of road that no one had gotten around to paving, men on horseback, kids leading burros, cows, pick up trucks carrying gigantic, loosely tethered cargo, buses with people riding on the top, flatbed trucks with 60-foot logs rattling away, more cows, dead dogs covered with frightening black clouds of vultures, and barefoot vendors with peeled oranges, bags of soft drinks, tamales, back scratchers, and loose cigarettes, all standing way too close to oncoming traffic, and sometimes even in the middle of the road. All of these nightmares were shrouded in a smog of exhaust and dust particles that hovered a constant three feet off the ground.

I had a death clutch on the steering wheel, but managed to pry my right hand loose, reach over, and switch off Linda Ronstadt. Music was too much of a distraction, and how many times had I heard “Blue Bayou” on this trip already? It was just as hard to tear my eyes from the hellish road; when it finally seemed safe, a quick glance showed me a James dead to the world, snoring slightly, mouth dangling open, looking quite a bit older than forty-three. My eyes and hands and mind fixed to the task at hand.

I drove for hours, deep into the Sonoran desert, where the traffic and the villages thinned out and I realized I had been clenching my jaw and my sphincter way too tight. The sun was setting to my right, a golden yolk dropping behind distant hills, setting the desert on fire. For a few minutes, everything was lit like a J.M. Turner painting, only a lot more arid. But here was night, drawing across the sky like a dark blue blanket, and then everything went black. I turned on the headlights and quickly switched to high beams, which flickered weakly through the still settling dust.

I noticed that the El Dorado seemed to be the only car going in either direction that had a working pair of headlights. Most drivers felt that the light of the moon was all the illumination they needed, while some cars had a single, dim headlight; I had to guess if it was the right or left one. It was like an awful game of chicken in some black and white teen movie. I crept along as far to the right of the road as possible, hoping no one was out for a stroll along the highway at seven at night, till I saw the flickering of a Vacantes motel sign. I didn’t care about cleanliness, price, nothing. I wanted out of the car.

After a night spent in an iron bedstead and a breakfast of tortillas and beans washed down with Nescafé, I said to James, “I am never driving in Mexico, day or night, again.” James teased me as a coward, and did the day’s drive, which was uncannily identical to the one the day before, with as much aplomb as if he had been toodling down Chicago’s Lakeside Drive. But that evening, when James got to experience the odd penchant Mexicans have for driving through the pitch dark countryside with their headlights off, he surprised me by pulling into a motel after only eleven hours behind the wheel.

By late afternoon of our third day in Mexico, we were winding up the mountains behind Acapulco, chasing the last rays of sun vanishing off in the west. We crested the top, and there, slipping in and out of sight as we made the hairpin turns downward, was Acapulco Bay, just visible as a silvery gleam separate from the velvet sky, where a thousand lights sparkled. James sighed, smiled, and reached over to take my hand. We were back.

It only took a few hours for James to find a place for us. Our home for the next few months was not oceanfront; it was even farther up the hill than the apartment I had shared with the three French Canadian girls. The building looked like a motel. Three blocky two-bedroom units shared a single umbrella table, four lounge chairs, and a shallow little pool that did have an eye-popping view of Acapulco. The other two units stood strangely empty the entire time we lived there. Our rent included daily maid service. A tiny, silent woman came in every morning, made us coffee, cleaned the apartment, took away our dirty laundry, and always asked if we would like lunch. James couldn’t or wouldn’t think ahead to meals, but once she left us a plate of chicken sandwiches that was one of the most delicious things I have ever eaten.

James and I fell back into last winter’s languid pleasure-seeking days, with only a few modifications. His budget did not allow for a season’s membership at a private beach club or for daily water-skiing. James shrugged off these deprivations without losing too much of his self-esteem. “Next year,” he told me.

When I had first met James he could go days without checking his portfolio, confident that his stock picking acumen meant that there was nowhere to go but up. Now every morning we drove down to the Sheraton’s newsstand, where James bought yesterday’s New York Times, lit a cigarette, and nervously tore through the papers to the stock market quotes.

James’s mood depended on that day-old news. If his stocks were down, he was furious with frustration: he had no way of contacting his broker other than waiting in line for hours at the sweltering office of the inept Mexican telephone company to make a long distance call. On those bad days I could look forward to hours of James taking on all comers at backgammon at the Villa Vera. He believed he could recoup some of his stock market losses by gambling, and he was desperate to prove to himself that he was a winner. He did win a lot, having the sharpie’s eye for novice players who were easily scalped, or blowhards who James taunted into making stupid moves and accepting hopeless doubles. His obsession left no time for meals. I spent those days at the Villa Vera swim-up bar, trying to fill up on bullshots (vodka and beef consommé), and wondering what our Mexican maid would have served for lunch.

The blessed days his stock posted a bit higher, the old preening, confident James reappeared. On one of those mornings James looked up from the business section with his vulpine grin and said, “Let’s have breakfast.” He took the paper and me to one of the Sheraton’s palm-shaded beachside tables, where I devoured a cheese omelet and everything in the bread basket, just in case. James was scribbling on the stock quotes and I was licking the last delicious buttery crumbs off my fingers, when a good-looking man, American by haircut, demeanor, and madras shorts, walked up to the table and introduced himself.

He was the director of a commercial promoting Mexican tourism and the model they were supposed to be filming that day hadn’t shown up. The director asked me, “Would you like to be in the commercial? I can pay you a hundred dollars. All you have to do is run back and forth on the beach for an hour.”

James piped up, “Yes, she’d love to!” while I felt a sharp pang of regret about the four buttered rolls I had just eaten. I was wearing nothing but my cute bronze bikini, a shade darker than my skin, held together in strategic places by golden rings.

I followed the director down to where the waves frothed on the shore. It was the perfect Acapulco day, so gloriously sunny and balmy that it would inspire any snowbound Midwesterner to immediately start packing his bags.

The director pointed up and down the beach, in case I didn’t know where it was, said “Okay, start running,” and then yelled something at the cameraman. I ran, hopped, skipped, splashed, smiled, waved, and jumped around like an idiot, followed by the cameraman and the director, who kept yelling “Happier! Look happier!”

James stayed back at the Sheraton, stretched out on a lounge chair, admiring his handiwork each time I ran by. When it was over the director handed me a hundred dollar bill and promised to send me a copy of the commercial. At least I got the money. I saw the commercial once on TV, and only recognized it because my first thought was, “Hey, I have that same bikini.”

My sudden and accidental elevation into a professional model was a bigger boost to James’ ego then it was to mine. At the Villa Vera, he called me up from my swim-up bar stool to introduce me to yet another backgammon pigeon, saying, “This is my girlfriend, she’s a model.” James beamed as if he had sculpted me himself, a wolfish Pygmalion, and stroked my butt for good luck. Look, he was signaling his opponent, look at me, lucky and successful, a winner with a sexy young girlfriend. And now I’m going to beat the pants off you. Most of the time, he did. I was rewarded for my supporting role with thin gold chains for my wrist and neck, bijoux de plage, the sales lady said, simple and elegant. I still thought the uncut emeralds would look just fine on the beach.

For a few weeks, as his stocks kept ticking upwards, James gleefully slaughtered all comers at backgammon, and we were back in the Acapulco groove, as if no time or money had been lost, back to waterskiing in the morning, afternoons at Le Club (our entry into this private, posh oasis bought by James with a folded bill discretely palmed to the maitre d’), Carlos ’N Charlie’s for drinks and dinner if James was eating that evening, then always, always dancing at Armando’s.

It was the last good time.

One morning, James opened the New York Times to the stock pages and a black cloud covered his face and mood. This cloud did not blow away, but grew heavier and more ominous each day. There was nothing I could say, nothing I could do, except that hope tomorrow’s news would be better. It wasn’t, and neither was the next day’s. There was nothing James could do either, except watch his fortune evaporate. There was no more waterskiing, no more afternoons watching the peacocks strut around Le Club’s enormous pool. James got up in the morning, threw back his coffee, and headed straight for the Villa Vera. In their shadowy backgammon room James challenged his opponents to higher and higher stakes and became aggressively reckless with the doubling cue. It didn’t matter if he was winning or losing, I couldn’t bear to watch. I was grateful whenever James forgot to call for his lucky charm before facing a new opponent.

It didn’t seem possible, but meals became even more irregular. I looked in the mirror: I was model-skinny. James went from thin to cadaverous. Even though the sun shone every day, we carried our own bad weather with us. The fun, the glamour, were gone. We didn’t dance any more; James showed up nightly at Armando’s because that was what a happening guy in Acapulco did. He watched the happy couples on the dance floor and threw back vodka and sodas. I held my hands over my flip-flopping empty stomach and tried to figure out what would happen next.

It did not surprise me when James turned outlaw. There was always something felonious about him, a suspicion that there was a crime in his past or in his future.

Enough of winter had passed that it was safe for James to go back to Chicago without loss of face. He began planning our drive north, a plan that now included drug smuggling.

The President with the Most Successful “First 100 Days”

The concept of the “first hundred days” reduces a large, complex undertaking — the achievements of a president — to a deceptively simple scale.

Franklin D. Roosevelt first used the term on July 24, 1933, to describe the early accomplishments of his administration. In a radio address to the nation, he said it was time to look back at “the crowding events of the hundred days which had been devoted to the starting of the wheels of the New Deal.”

FDR’s accomplishments were impressive. He called the 73rd Congress into session early, and before his first week was over, presented his Emergency Banking Act.

At the time, banks across America were failing at a fearful rate. Fourteen hundred banks had shut their doors in 1932. Before 1933 ended, another 4,000 banks would close. The Emergency Banking Act closed every bank in America for one week, enough time for the public panic to subside. When the banks reopened, Americans began re-depositing their savings.

The Act was only the beginning of Roosevelt’s initiatives over the first 100 days. Before Congress adjourned, the administration also

- took U.S. currency off the gold standard, effectively allowing the government to print and distribute money to the struggling banks

- imposed regulations on U.S. banks that separated commercial banking from investment banking, and prohibited banks from using their assets in stock market speculations

- established an insurance program for bank accounts (the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation)

- introduced new regulation of the stock market (creating the forerunner of the Securities and Exchange Commission)

- created an agency that paid farmers not to raise crops, in order to raise the prices they got for their produce

- launched the Civilian Conservation Corps, which eventually put 250,000 young men to work on conservation projects

- started a program (the Tennessee Valley Authority) to provide electricity to impoverished rural Americans and raise their standard of living

- created a controversial program that placed pricing controls on businesses in an effort to raise the cost of goods

- began the Public Works Administration to create jobs building schools, hospitals, airports, dams, and other public projects

- provided training and direct relief to the unemployed

If it seems impossible for a president to accomplish all this in 100 days, it is. Roosevelt couldn’t have done this on his own, and he knew it. He relied on three other factors.

The first was Congress. Most of the changes came through legislation, not executive orders. Roosevelt knew he could rely on the support of other Democrats who made up the majority in both houses. (The 73rd Congress had 311 Democrat, 117 Republican, and 5 Farmer-Labor representatives in the House; and 59 Democratic and 36 Republican senators, plus one from the Farm-Labor Party.)

Second, there was a national sense of urgency. One in five Americans was out of work. Employed Americans feared their job or savings might disappear overnight. Congressmen knew they had to act, even to try unconventional means. Southern Democrats sometimes objected to Roosevelt’s program, but progressive Republicans from western states stepped in to throw their support behind the president.

Third, Roosevelt had strong support from the American public, which had just elected him by 472 electoral votes to President Hoover’s 59. (Hoover lost the popular vote in 1932 by the same sizeable percentage he’d won it in 1928: 17%.) They had voted for, and would support, any new measures.

Other presidents haven’t had those advantages. When President Johnson entered the White House, he enjoyed a honeymoon phase with the press and the public. It enabled him to push the Civil Rights Bill, which had been hung up in Congress. He introduced a wide range of bills, hoping to beat Roosevelt’s record, but he failed.

President Reagan’s first 100 days got off to a promising start when 52 Americans being held hostage in Iran were released on the same day he took office. He also proposed $41 billion in budget cuts and major tax breaks during his first three months. President Obama took action on an ambitious number of foreign and domestic issues, including a $700 billion stimulus bill, but he still fell short of FDR’s record of change.

Roosevelt still holds the record for accomplishment in his first 100 days in terms of major legislation passed, but considering that it took a financial disaster and a desperate sense of national urgency to achieve so much, perhaps it’s just as well we never see his record beaten.

Featured image: Shutterstock