No Sweat Tech: How Technology (Yes, Technology!) Can Help You De-Stress

Almost everybody is under a lot of stress these days, between politics, climate change, the wildfires in Australia, a new virus spreading around the world. So I’m going to look at ways you can calm down, rela— well, relaxing might be too much to ask for, but de-stress. There are sounds you can use, sights, and exercises. And if using these doesn’t help, I’ll give you a few places where you can talk to someone about how you’re feeling for free.

Soothe Your Ears

Usually when I work, I like it silent. But sometimes I find myself getting a little antsy or restless. I need some sound to settle me down. But I don’t try to find just the right music; instead, I look for some ambient noise. Via your speakers, you can recreate anything from a crackling campfire to a gentle rain to the Slytherin study room at Hogwarts. Here are three of my favorite noise generators.

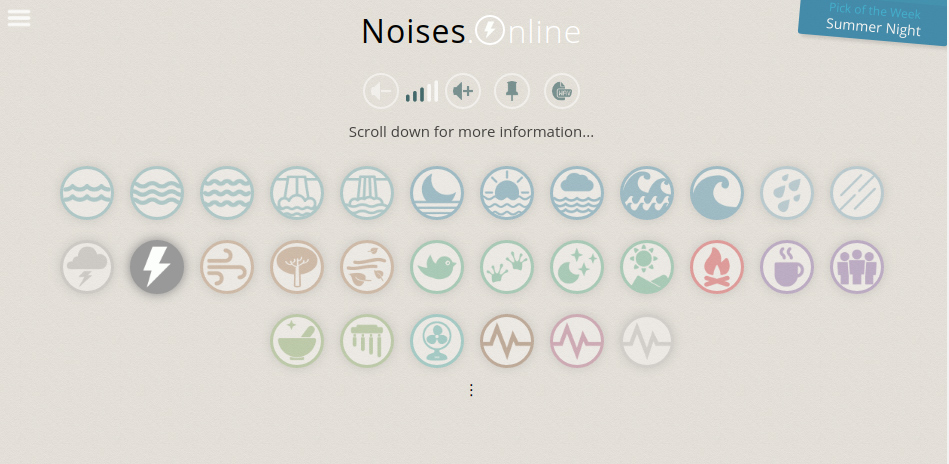

Noises Online

At first glance Noises Online looks pretty complicated, but it’s really not. Each icon is a kind of sound. Hold your mouse pointer over it to see what kind of sound. If you click it, the sound comes on. If it click it multiple times, the sound quiets until it turns off completely. You can click multiple sounds to make a soundscape. For example, I made a nice audio collage of a crackling fire, ocean waves, and windchimes. There’s also a button to make a .WAV sound file of your selections so you can download it and take it with you. If you scroll down a little there are even more options for the tone and liveliness of your selection.

If you’re feeling intimidated, click on the “Pick of the Week” in the right corner to see how the site works. Summer Night features a chorus of frogs, a brook, and the gentle sounds of a warm evening.

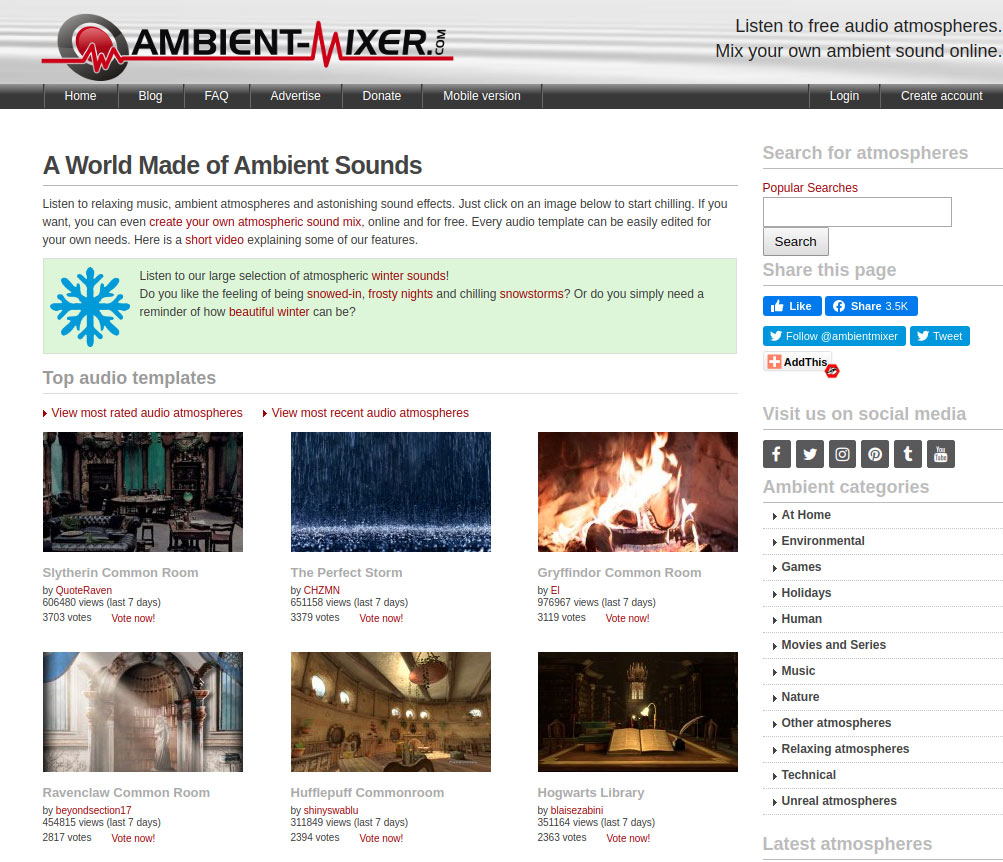

Ambient Mixer

Ambient Mixer is less about individual sounds and more about making up a soundscape. The site has what must be thousands of different soundscapes for you to browse through via its category system, or search by keyword.

I did a search for campfire and got 743 results. After browsing for a while (the biggest problem with this site is that you can wander around in it for hours) I found “Rainy campfire while reading,” which was a nice mix of rain sounds, campfire, and someone drinking coffee. If you don’t like the mix available, you can adjust it with the mixer that’s built into the soundscape’s page.

I can imagine this site would be useful for all kinds of things. Writing and need a particular kind of atmosphere? Having a themed party? I bet you can find a relevant soundscape here.

Listen to the Clouds

This one is a little different, so bear with me. Listen to the Clouds is a web site that blends audio feeds from air traffic controllers with ambient music from SoundCloud. Pick an airport (they are arranged by location) and the site will load the audio. Sometimes airports are offline, and in a few places (like Germany, UK, and Spain) there are no feeds available at all. I like to choose airports that don’t use English, because otherwise it can be distracting. Once you find a feed that you like, you can select an ambient music piece underneath it, individually controlling the volume of each item.

Odd option for relaxation, isn’t it? But the soothing ambient music and the calm, usually flat delivery of the air traffic controllers provides an “everything’s okay” vibe which can help you relax and focus on your work. One note: I use ad and cookie blockers in my browser. They completely broke this site. If you have a lot of browser extensions installed, try using this site in an incognito window (in Chrome, this means your browser extensions don’t apply) first.

Easy on Your Eyes

Ever just wanted to watch TV and distract your mind? You don’t want people yelling or things blowing up, you just want to settle down, turn on the screen, and zone out. Or maybe you want something playing in the background for a little company. If that’s the case, check out slow TV.

Slow TV isn’t a particular program, it’s a type of programming; ordinary things, done at ordinary speed, in ordinary time. This might be a train ride, or a fire burning in a fireplace, or someone knitting. There’s a web site called Watching Grass Grow that’s just a live video feed of a lawn so you can watch grass grow.

When I want some slow TV, I find that searching YouTube for the words slow TV and either a place or a thing name works well. For a place name, countries work better than states, and cities don’t work well at all unless it’s a famous city. For things, you’ll have to experiment a little. Slow TV landscape and Slow TV space will find you interesting videos, but I can’t help you if you insist on searching for Slow TV spaghetti.

What kind of things do you find? Searching for Slow TV Japan found me train rides, walks around cities at night, and similar calming things. Searching for Slow TV Georgia led me to discover BigRigTravels, a YouTube channel apparently set up by a long-haul trucker who livestreams his drives.

Of course, you’re not supposed to pay close attention to slow TV. You can watch for a while, get distracted, close your eyes, think about something else, maybe even take a little nap. And that’s the whole point.

Calming Exercises

Up until now we’ve looked at things you can do passively to relax — sounds and videos you can take in. But there are deliberate exercises you can do as well to help you maintain equilibrium.

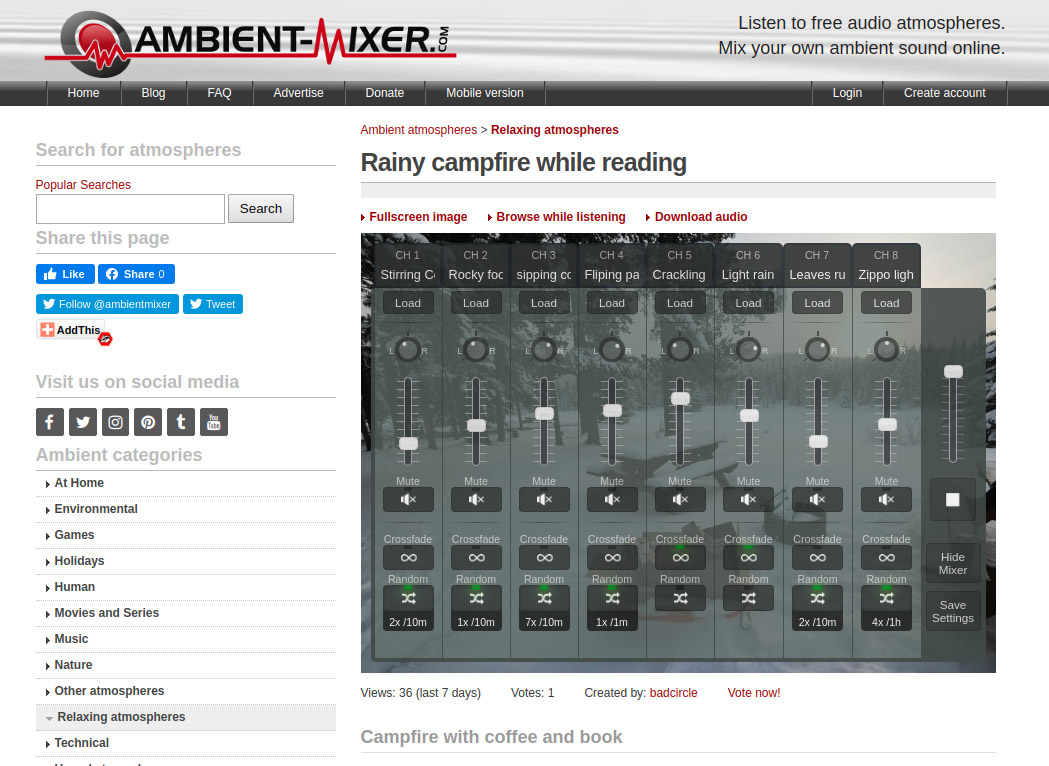

Breathe Slowly

Isn’t it weird? Breathing is our core necessary function. If we don’t breathe, we die. And yet it’s so easy to forget to take deep, full breaths. If you get stressed you might find yourself taking shallow breaths or even holding your breath as if you’re bracing yourself. Breathe Slowly is an animated circle that grows larger and smaller as it reminds you to inhale and exhale.

After a few minutes of breathing along with the circle, you might find your shoulders settling down a little. If you find the circle goes too fast or too slow, click on the menu in the upper right corner to adjust the speed.

Stress Analyst

I suspect this site is one of those you’re either going to love or hate. So if you visit this site and find yourself going “ugh!” that’s okay. Skip it. Stress Analyst is a site that walks you through the anxiety and stress that you’re feeling. You’re asked to answer questions about how you’re feeling and strategies you could use to de-stress. As you’re answering questions, the site periodically asks you about your stress level.

You might find this approach validating and reassuring. Or you might find it annoying and perhaps patronizing. Personally when I’m feeling really stressed, I like a third party kind of taking me through all the facts I tend to forget (that stress is a physical reaction, you can take steps to counteract it, etc.). It’s a quick process and could be useful when you just want to check in with your own feelings.

Pixel Thoughts

Pixel Thoughts is a 60-second exercise designed to help you get over anxious repetitive thoughts. You’re asked to put your thought in a star, and then the star floats away as you’re reminded of the vastness of the universe and how incredibly tiny your thought is compared to it. Then the star vanishes into the star field.

(This is kind of an off-label use, but this site can also help you when you’re feeling really angry and don’t have an outlet. It’s cathartic to fill the star with swear words and then watch it float away.)

When You Need Help

Sometimes gentle music or slow TV can’t help you. You might be panicky, with racing thoughts, and you can’t seem to steady yourself. If you think you’re in immediate danger, please call 911 and talk to humans who can help you immediately.

But if it’s not that much of an emergency, then there are some ways you can talk (or chat, or text) someone who can point you to helpful resources, or just listen. (Isn’t it amazing how often we can feel better if someone just listens to us for a little while?)

Suicide Prevention Lifeline

Put down the mouse and pick up the phone. The front page of Suicide Prevention Lifeline has an 800 number you can call immediately. The crisis worker you can reach will listen to you and can connect you to resources to help. You don’t have to be suicidal to call this number; maybe you’re depressed, or worried, or you’re really lonely. This number will get you to someone who will listen, and who cares about you. The site also has resources for specific kinds of struggles and concerns.

(What did I hear? Did I hear someone say that their problems aren’t important enough to call this number? You stop that right now! We are not having a problem comparison contest. Or if we are, then I’m the judge and I say your problems are important enough and you are important enough. Pick up the phone.)

Crisis Text Line

Sometimes when you’re really upset, you don’t want to talk on the phone. Or maybe you don’t like talking on the phone anyway. Crisis Text Line provides numbers for people in the US, UK, and Canada to text and talk to someone. The site describes its mission as helping people “move from a hot moment to a cool moment,” which is a great way to put it. Like the Suicide Prevention Lifeline, this resource is not just for those with suicidal thoughts but, as the site says, “it’s any painful emotion for which you need support.” It’s available 24 hours a day.

IMALIVE

Don’t want to call, don’t want to text? Maybe you want to chat. IMALIVE has a crisis chat available 24 hours a day if you’re feeling stressed and need to talk to someone. In addition, IMALIVE does “mental health fairs” at college campuses around the country. The site’s blog has stories of other people sharing their experiences with stress and anxiety. Knowing you’re not alone may help.

“All times are hard times sometimes,” as my Granny says. It’s only human to have times when you feel anxious and unbalanced. There are lots of resources online that can help you, and if those aren’t enough, there are people who can help you too. I wish you the best, happiest, healthiest, most love-filled year you can possibly imagine.

Featured image: Screenshot from Breathe Slowly (https://xhalr.com/)

Tired of the Daily Din? It’s Time for the Quiet Diet

Here’s a worthy challenge: Try escaping the daily din of American life. It’s not easy. Maybe, for instance, you don’t actually want to hear Wolf Blitzer’s voice blaring from every TV planted in a public space. Who’d blame you?

Unfortunately, most of us are constantly assaulted by a never-ending bleating, clanging, whirring, and buzzing — the raucous background music of 21st-century civilization.

It’s more than merely annoying, which would be plenty bad enough. It also undermines our ability to work productively. Worse, it may be doing harm to our brains.

While the cacophony is not an entirely new phenomenon — except for the chirps of our omnipresent tech devices — it nevertheless constitutes a palpable torture for many of us. You know that androgynous figure who expresses universally understood “agony” in Edvard Munch’s famous painting The Scream? Well, then you get the idea.

The most troubling part of noise pollution is that it can result in permanent hearing loss, anxiety, and hypertension. Some say even coronary artery disease. Such trauma! At the very least, don’t we all badly need some alone time, where we can focus? An obviously good idea, I’d say. It is hardly a surprise, then, that so many of our fellow Americans seek refuge in the isolation of parks and forests.

Noise is, of course, a serious problem chiefly in urban areas. It was in New York City, unsurprisingly, where she could no longer abide the background roar, that Julia Barnett Rice, wife of a wealthy businessman, founded the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noise. That was 113 years ago. Mark Twain signed on as spokesperson for the group. Its one lasting legacy: the widespread adoption of legally enforced quiet zones around schools and hospitals.

Mice, when exposed to two hours of silence every day, developed new cells in the region of the brain that controls memory, emotion, and learning.

But even far from our cities, anti-noise battles rage. Those who lead the charge — arguing for better noise-abatement legislation and comity among oft-disrespectful neighbors — do so with increasing evidence to support the cause.

These days, they can bring to their campaigns evidence showing that quiet is provably beneficial. Six years ago, the journal Brain Structure and Function published a study indicating that mice, when exposed to two hours of silence every day, developed new cells in the region of the brain that controls memory, emotion, and learning. Not exactly a duh! moment in the annals of laboratory experimentation, but a revelation nevertheless.

Additionally, recent studies — with humans — offer yet more support for those of us who believe that quiet is among our basic human rights — the right to maintain our personal well-being. People who meditate, this research has found, often see a significant delay in the onset of brain deterioration. In essence, by carving out a quiet interlude every day, meditators remain intellectually youthful longer.

These discoveries free those of us who long for a quieter country to confront our neighbors about such matters as dogs that just will not stop barking. Or, more urgently, streaming rappers who just will not stop rapping. At the very least, in our cranky way, we can present Actual Science to explain why the noise sets us off. All we want, after all, are fresh brain cells.

And then there is the enduring mystery of what’s known as the Hum, an anomalous, barely detectable noise heard almost everywhere around the world. Does it come from electromagnetic signals? Underground pipelines? No one knows. But scientists keep looking into the Hum. However bad it is, in my opinion it’s not nearly as maddening as many amateur YouTube videos. So, for now, I choose to sit — in quiet, when possible — and blissfully ignore its existence.

In the last issue, Cable Neuhaus wrote about luxury sneakers.

This article is featured in the November/December 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

Does Our Primitive Survival Instinct Still Work in the 21st Century?

Our survival instinct, which has served us so well since we climbed out of the primordial muck eons ago may now be failing us. Why? Because the fight-or-flight reaction that arises in response to a threat to our lives is often no longer effective in a world that is far more complex, unpredictable, and uncontrollable than that of our primitive ancestors’ from which the survival instinct arose. In this article, I want to explore this disconnect between our survival instinct and what kind of new survival instinct might work better today.

At the heart of fight-or-flight are what I call the “Big Three” crisis reactions : fear, gloom, and panic.

Fear

First, the emotional reaction of fear is instantaneous and intense, ensuring that we pay attention and respond to a perceived crisis. In other words, fear causes us to act fast! Fear paralyzes our ability to think clearly, identify problems, and make deliberate decisions because thinking takes time and there just wasn’t enough time back in the cavepeople days for that; the only viable options were to fight or flee, immediately!

Unfortunately, many of today’s threats can’t be fought because there is no readily confrontable enemy (think terrorist attacks, climate change, and job loss). And they can’t be run away from because many are diffuse rather than localized; you can run, but you can’t hide. And burying your head in the sand may work for ostriches, but for humans, it leaves a very important part of the body exposed!

Gloom

Second, gloom can work if the crisis is clear and present. In prehistoric times, focusing on the negative dimensions of a threat — namely, what can go wrong in the near term — ensured that we stayed vigilant to the most relevant dangers, allowing us to respond most quickly. By focusing on the negative aspects of the crisis during primitive times, our ancestors had the simple choice of fighting or fleeing. These primitive threats were also usually short lived — for example, an attacking animal or rival tribe — so gloom had no long-term implications.

But today’s crises are often amorphous, distant, and long lasting. So the initial gloom, which had short-term survival benefits, can become a self-fulfilling prophecy that can worsen the threat. We saw this play out during the Great Recession. Many people distrusted the stock market, many businesses had little confidence in their own survival, and governments lost faith in their ability to overcome the crisis. In all these cases, an attitude of gloom led to behavior that may have actually worsened the financial crisis.

Panic

Third, panic produces immediate and frenzied behavior. Panic was quite functional back in prehistoric days because it triggered in our ancestors either a furious attack or a frantic retreat from the threat. Panic in reaction to many of today’s crises, however, produces actions that are more ill-advised and destructive than helpful. Where there should be patience, there is haste. Where there should be reasoned deliberation, there is irrationality. Where there should be calm, there is, well, panic.

In the panic after the fall of the investment bank Lehman Brothers and the stock market crash that followed, many people fled the financial markets, many businesses drastically cut costs by letting go of employees, and governments went into austerity mode at the worst possible time. All of these efforts were intended to ensure everyone’s respective survival, but such panicked behavior was short-sighted and had the exact opposite effect in the long run.

A New Survival Instinct

If these instincts that are so deeply woven into our DNA no longer fulfill our most basic needs to survive, what new form of survival instinct do we need to evolve to help us to endure in the concrete, metal, and hard-wired jungle in which we now live? As with earlier stages of evolution, we need to adapt to our surroundings and produce a response that will be more effective than the fight-or-flight reaction that helped us survive for hundreds of thousands of years.

But we can’t wait millions of years for evolution to do its job and ingrain a new survival instinct in us that is more functional for the modern world. In fact, we can, to paraphrase a well-known adage, take evolution by the horns and bend it to our will with a new survival instinct that is the antithesis of the time-worn fight-or-flight reaction. Instead of overwhelming and uncontrollable fear, a crisis should trigger courage, which isn’t the absence of fear — it’s impossible to not to experience fear in the face of a threat — but rather the ability to confront the fear and act proactively and deliberately despite it. It involves being able to manage negative emotions, such as fear, anger, frustration, and despair, and to generate helpful emotions, including hope, inspiration, excitement, and pride.

Instead of gloom, we should engage in rational thinking that includes calculated risk-reward analysis, in-depth problem solving, and effective decision making. It means being cognizant of the threat, but focusing more on finding solutions to overcome it. In a crisis that encompasses a group (e.g., work, family, team), this reasoned thinking requires that people set aside differences, communicate openly, establish priorities, and work together — because that is the rational thing to do in the face of significant societal crises — to produce answers to the pressing dangers that today’s threats present to us.

Finally, we don’t need to wait for evolution to adapt our survival instinct to today’s challenges. Rather, we already have the capacity to override our primitive survival instinct. We are already capable of experiencing courage, thinking rationally, and acting deliberately. That is the gift that evolution has also given us; it’s called the cerebral cortex.

Tips For Responding to a Crisis

Instead of panic, we should take calm and measured action that is directed and purposeful. This new survival instinct can increase our chances of surviving during periods of crisis. What results is a psychology—what I call an ‘opportunity mindset’— that is diametrically opposed to and entirely more effective than the survival instinct that now dominates our DNA and our lives.

Of course, the real challenge involves how to resist those millions of years of evolution and stop the instinctive flight-or-flight reaction before it takes complete control of us. Here are a few tips for ingraining a more evolved response to a crisis:

- Stop!: Instead of a knee-jerk reaction to a threat in your life, take a break and gain some physical and emotional distance from the threat. With this separation, your survival instinct will diminish and make it easier for you to engage the higher-order thinking of your cerebral cortex.

- Relax: When your survival instinct is triggered, it activates your ‘sympathetic nervous system’ which puts your body into overdrive with increased heart rate, blood flow, and adrenaline. This reaction helped in the past, but doesn’t do much good with most present-day threats. Take some deep breaths, relax your body, and center your mind.

- Seek support: Crises of all sorts, whether a saber-toothed tiger or the loss of a job, are more manageable when you know that you have others in your life who can support you. So, when a threat arises, look for people who can provide you with emotional and practical support to address the crisis.

- Focus on what you can control: The nature of many of today’s threats is that they aren’t always within your control. But, there are always some aspects of a crisis that you can control, most notably, your reaction, attitude, and response to it. When a crisis arrives, identify what you can control about it and direct your attention there.

- Identify the problem/find a solution: At the heart of every crisis is a problem. If you can identify the problem, you may be able to find a solution to the crisis (of course, not all present-day crises have immediate solutions to resolve them).

- Set goals/make a plan: Crises often result in feelings of loss and destabilization, both of which are truly unsettling. Goals and a plan can provide you with clear direction and tangible steps to overcome the crisis with which you are faced.

- Take action: When presented with a threat, running away from it rarely works these days. Not only is the crisis still there, but you feel even more helpless to confront it. Rather than withdrawing from the threat, choose to take action aimed at overcoming it. You’ll feel more in control, less stressed, and, the big bonus is that you may actually resolve the crisis and remove the threat.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

Your Weekly Checkup: Psychological Distress Can Have Physical Consequences

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

Many people are distressed — maybe at work performing a job they don’t like or working for a boss who doesn’t like them. Or maybe they are stuck in a marriage that is on the rocks or struggling with misbehaving or uncontrollable children.

All of us, at one time or another, deal with stress in our lives. For most, the stress is transient and ultimately resolvable. But for some, the stress is longer lasting, even constant, severe, and insoluble.

These are the people I worry about because they are at increased risk for heart attacks and strokes. A recent study analyzed information from almost a quarter of a million participants with no history of heart attack or stroke. The investigators calculated and ranked psychological distress, such as fatigue, anxiety, depression, and hopelessness experienced by each participant within the previous four weeks.

When the study started, 16.2% of participants had moderate psychological distress while 7.3% had high or very high psychological distress, greater in women than men. Over the next 4.7 years, 4,573 heart attacks and 2,421 strokes occurred. The higher the degree of psychological distress, the higher the absolute heart attack and stroke risk among the participants. In men aged 45 to 79 years, those with high or very high psychological distress had a 30 percent greater risk for heart attack compared with those with lower psychological distress. The risk was less among men 80 and older. However, male sex added to the effects of the psychological stress. Among women, those with high or very high psychological distress had an 18% greater risk for heart attack compared with those with lower psychological distress and did not change with age.

The stroke risk also increased. Among those aged 45 to 79 years, high or very high psychological distress was associated with a 24% increased risk for stroke in men and 44% increased risk in women. Therefore, in woman, the magnitude of the effect of psychological distress appeared greater for stroke than for heart attacks. The reason for this is not known.

The results from this study — one of the largest of its kind — make it very clear that psychological stress has a strong, dose-dependent association with heart attacks and strokes in men and women, despite adjustment for a wide range of confounders.

How might the head impact the heart or brain to cause a heart attack or stroke? A recent study showed that patients who had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after a heart attack exhibited enhanced inflammatory responses to psychological stress. This observation provides a potential link — inflammation — between PTSD and adverse cardiovascular outcomes as well as other diseases associated with inflammation.

What can distressed people do? In some instances, antidepressant drugs can reduce the risk for cardiac events. In 300 patients with depression following an acute coronary syndrome, a 24-week treatment with an anti-depressant, escitalopram, compared with placebo resulted in a lower risk of major adverse cardiac events after a median of 8.1 years.

If you are distressed or depressed, seek professional help. Much can be done to relieve the stress to make you feel better and reduce the risk for a heart attack or stroke.

The New Science of Stress

The irony is not lost on Barbara Joyce, a teacher from Tenafly, New Jersey. The 52-year-old wife and mother of three has plenty of stress in her life, from the beating her retirement savings took during the 2008-2009 financial crisis to her two daughters’ struggles to find employment in the jobless recovery. And to top it off, she was in Tokyo during the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Since her doctor reminded her that stress can hurt her health, she has taken up jogging, and says she “literally runs off stress.” She can’t escape it entirely, though, and worrying that it is increasing her risk of cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and possibly some forms of cancer causes her … even more stress.

The suspicion that there is a connection between psychological stress and health—especially heart health—goes back to antiquity. In the mid-20th century endocrinologist Hans Selye coined the term “stress,” and described how the chronic, unrelieved kind can cause pathology, largely through the release of stress hormones including cortisol and adrenaline. Now advances in molecular biology and neuroscience have brought good news and bad news about stress and health. The bad news is that newly discovered mechanisms triggered by an overload of stress cause changes in neurons and the immune system that are more extensive than ever before suspected—with consequences for conditions as varied as asthma, arthritis, hypertension, and HIV/AIDS. The good news is that there are more ways than ever to reduce stress, even if you don’t feel like strapping on a pair of running shoes.

Anecdotal evidence of how stress impairs health is everywhere. Ed Rogers, 66, a public health consultant in Louisville, Kentucky, swears that whenever his wife yells at him for shirking his share of the housework he has to grab his inhaler to stave off an asthma attack. Whenever David, 64, of Breckenridge, Colorado, gets “tired and frustrated by the turkeys one is forced to work with/for,” he says, it causes “tension in the shoulders and neck tending toward headaches.” (Not wanting to offend those “turkeys,” David asks that his last name be withheld.)

But the evidence goes beyond anecdote. Chronic stressors such as financial, work, or marital problems plus the attendant depression, hostility, and anxiety account for about 30 percent of heart attack risk calculate a team of Swedish scientists. And high levels of the stress hormone cortisol strongly predict the likelihood that someone 65 or older will die of cardiovascular disease, as scientist Nicole Vogelzangs of VU University Medical Center and colleagues in The Netherlands found in a 2010 study. Previous research had “suggested that cortisol might increase the risk of cardiovascular mortality, but until now, no study had directly tested this,” said Vogelzangs. But her work found that people in the top one-third of cortisol levels are five times more likely to die of cardiovascular disease than those in the bottom one-third.

In one of the most elegant demonstrations of the link between stress and heart attacks, researchers at The University of Western Ontario (UWO) measured cortisol levels in hair, which is like examining tree rings to determine when droughts and other climate calamities occurred. Hair grows about 1 centimeter—just under half an inch—per month, explains UWO’s Gideon Koren, “so if we take a hair sample six centimeters long, we can determine stress levels for six months by measuring the cortisol level.” Using that approach on 56 men who had recently suffered a heart attack, he and colleagues found that the men had higher cortisol levels in the previous three months than comparable men hospitalized for other conditions, they reported last year.

“Experiments of nature” have offered dramatic demonstrations of the deadly effects of stress. Immediately after the 1994 Los Angeles earthquake, the number of cardiac deaths spiked two to five times the normal rate. And after the 9/11 attacks, the rate of defibrillator firings over the next month was two to three times normal, as the number of people whose heart needed to be shocked back into a normal rhythm soared as a result of chronic stress. But stress that falls short of the Richter scale and a terrorist attack can also harm health. Work, not surprisingly, is the stress mother lode. People working 50 hours a week or more are 13 percent more likely to report hypertension than people working 40 hours a week, and a stressful job with little decision-making authority raises blood pressure rates even during sleep.

Stress can harm health in two basic ways. One is by leading us to fall into unhealthy habits such as sleeping poorly, being less likely to exercise, smoking, and eating unhealthy foods (especially sugars and fats). The American Heart Association reports that 20 percent of Americans are worried that stress will affect their health—yet 36 percent of them say they deal with stress by drinking alcohol or eating. Result: a self-fulfilling prophecy. The poor health habits that result from stress account for an estimated two-thirds of the additional risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular illnesses in people with depression and anxiety, found a 2008 study in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

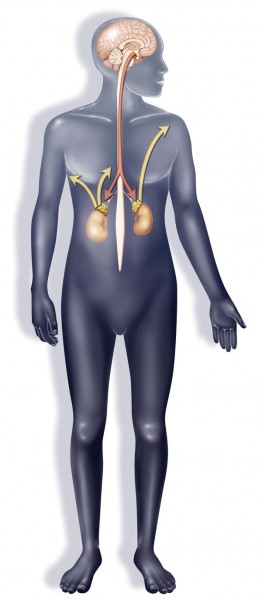

The other path from stress to illness winds through the endocrine, or hormone, system. Stress causes the brain’s hypothalamus to send a message to the adrenal glands, which sit just above the kidneys, to release cortisol. That may seem like a design flaw, but in fact cortisol helps the body recover from acute stress, including by raising blood sugar—the better to help you flee a saber-tooth cat. (The adrenals also release adrenaline, or epinephrine, and the related norepinephrine.) But trouble begins when too much cortisol is released, or when it is released unnecessarily—that is, not in response to an actual and immediate threat but to background anxiety—and remains chronically elevated. High cortisol levels cause chronic inflammation, which can cause arthritis to develop or worsen, and trigger the release of immune-system proteins called cytokines, implicated in such age-related diseases as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and type 2 diabetes.

How Stress Impairs Health

In Greek mythology, the monstrous Hydra terrorized visitors to a mystical lake. Beheading the Hydra was no easy task because it grew two new heads whenever one was cut off. The multiplying evil of the Hydra offers an apt analogy to the insidious ill-effects of stress in modern life. Chronic high levels of stress bring on a world of trouble on multiple body systems and can lead to…

Worsening of Asthma symptoms

This condition is marked by inflammation of the airways, so it’s no surprise that stress, by causing inflammation, increases asthma symptoms. A University of Wisconsin study showed how. When students with asthma inhaled an allergen (ragweed, dust mites, or cat dander), lung inflammation was 27 percent higher during finals than during a low-stress period—even though the allergen exposures were identical.

Cardiovascular disease

Stress increases blood levels of inflammatory molecules (called IL-6, C-reactive protein, and fibrinogen). These bad actors promote the development of atherosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries. The inflammatory molecules that trigger atherosclerosis also make the fatty arterial deposits called plaques more likely to rupture, causing a heart attack or stroke. Stress also causes the nerves to flood the bloodstream with a molecule called neuropeptide Y (NPY), which raises heart rate and blood pressure. NPY stimulates the growth of abnormal smooth muscle in blood vessels, which leads them to become blocked with plaque-like deposits of microphages, thrombus, and lipids.

Faster weight gain

NPY also seems to be the culprit behind our tendency to overeat and gain weight when we’re stressed. It throws a monkey wrench into the brain’s appetite-regulation system, and can also “unlock” receptors in fat cells, stimulating them to grow in size and proliferate. That also seems to be an evolutionary adaptation—early humans benefited from putting on fat in response to stress, which tended to be of the “mammoths are scarce this year” variety rather than the “I can’t make my mortgage payment” kind. As a result, a physiological response that was adaptive in the past is harmful today: We put on a nice layer of fat that doesn’t actually help us cope with the source of our stress. The effect is so powerful that stressed mice on high calorie diets gained twice as much fat as unstressed mice on the same diet.

High cholesterol

One reason mental stress can raise cholesterol levels may be that stress encourages the body to produce more energy—to fight or flee—including fatty acids and glucose. Both substances cause the liver to produce and secrete more LDL, or bad cholesterol.

Impaired immune system

Although scientists have long suspected that stress undercuts the immune response, only now has the mechanism behind that connection become clear. When we are stressed, the flood of NPY impairs the immune-system cells whose job is to fight infections. As a result, colds, flu, and other viral diseases are more likely. So are virally caused malignancies such as cervical cancer, which can be triggered by the human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV infection alone is not sufficient; the immune response causes most HPV infections to disappear. But, with stress in the mix, precancerous cervical lesions are more likely to progress to cancer.

Weakened response to HIV

Stress can bring about changes that allow the HIV virus to replicate more quickly, accounting for much of the variability in how people respond to an HIV infection. By keeping stress under control or avoiding stressors an HIV-positive person is more likely to remain asymptomatic for long periods rather than progressing to AIDS and is less likely to suffer opportunistic infections.

Increased risk of dementia

Psychological stress in middle age can raise the risk of dementia, especially Alzheimer’s disease, in old age. Scientists at Sweden’s University of Gothenburg followed 1,400 women for 35 years, asking them about their levels of psychological stress in 1968, 1974, 1980, 1992, and 2000 to see who developed dementia. Women who reported repeated periods of stress in middle age were 65 percent more likely to eventually develop dementia than women who did not. In women who reported stress at all time points, the risk was more than twice that of women who had escaped stress. So what’s the connection? A solid body of research shows that stress hormones called glucocorticoids are toxic to neurons and to the synapses that connect them, a phenomenon dubbed “neurostress.” The fewer synapses in a brain, the less of a cognitive cushion it apparently has after age-related mental decline sets in.

Premature aging

Psychosocial stress can reach into our very DNA, altering the “telomeres” that sit at the ends of chromosomes like the plastic tips at the end of shoelaces. Telomeres become shorter as the cell (and the person) ages. When enough telomeres reach a critically short length, the chromosome unravels like a shoelace that has lost its tip, and the cell stops dividing. This can trigger or contribute to age-related diseases. People under chronic stress have shorter telomeres and less of the enzyme telomerase, which repairs that damage, find scientists led by Ronald Glaser of Ohio State University.

Increased risk of cancer

This one’s a big “maybe.” The problem for scientists is that it is almost impossible to know whether a stress-free immune system keeps nascent tumors in check. Micro-scopic tumors are almost impossible to detect, so researchers can’t tell whose are being quashed by a healthy immune system and whose are being allowed to proliferate by a stress-impaired immune system. A 2007 study found that, in cell cultures, the stress hormone norepinephrine can ratchet up biochemical signals that stimulate tumor cells to proliferate. And in multiple myeloma cells growing in lab dishes, norepinephrine can increase production of proteins that foster metastasis. “For years it was thought that the immune system plays no role in cancer,” says immunologist Peter Lee of Stanford. That’s because cancer is part of the “self,” and the immune system targets only “non-self”—viruses, bacteria, organ transplants. But now, he explains, “We and other labs have uncovered multiple immune deficits in cancer patients.”

Harm to the next generation

Stress can jump the generation gap. A mother’s stress during pregnancy can influence the baby’s developing immune system in such a way as to make the child’s immune response go into overdrive. For example, such children are at higher risk for asthma and for allergies to dust.

Learn to be Stress Free!

As science keeps uncovering more ways that stress can impair health, there is also increasing confidence that you really can learn to lower stress levels. Researchers today understand more precisely than ever what it takes to control stress.

Aerobic exercise is an excellent place to start. Regular exercise, especially when combined with stress management training, can actually decrease cardiovascular risk in patients with heart disease.

The next step is to adopt principles of what’s known as cognitive behavorial therapy (CBT) focusing on stress management. CBT includes monitoring yourself for signs of stress and learning such stress-management skills as deep breathing and spiritual development. In studies, people receiving CBT had a 41 percent lower rate of both fatal and non-fatal heart events, 45 percent fewer recurrent heart attacks, and a 28 percent lower rate of death over the eight years that they were followed.

Stress management can improve physiological markers of cardiovascular health, found a 2011 study. It was the first randomized trial to show that something other than drugs can improve blood flow to heart, health of blood vessels, and ability of the cardiovascular system to regulate surges in blood pressure.

Even the way you fight can make a difference. A 2009 study found that when couples used words to indicate that they are thinking about their conflict in a rational way rather than making accusations they experienced smaller increases in cytokines after the fight compared to couples who fought irrationally.

Proper stress manage-ment can even impact your DNA. Herbert Benson, M.D., who coined the term “relaxation response,” finds that yoga, prayer, and a meditation-like exercise he developed—sitting quietly, relaxing your muscles, breathing rhythmically, and repeating a “focus” word when you exhale for 20 minutes—all lower heart rate, blood pressure, and inflammation. And, as he describes in his book The Relaxation Revolution, these calming activities affect DNA. Comparing experienced meditators to novices, he and colleagues found that 2,209 genes were expressed differently—that is, switched on or off—in the two groups. Among them: genes involved in the immune system, inflammation, premature aging, and oxidative decay implicated in heart disease and cancer. But after just eight weeks of stress-management training, Benson finds, hundreds of genes in novice meditators moved away from the stressed-out pattern and instead resembled one that has been “associated through past research with clear health benefits.”