Alexander Woollcott and the Wild World of the Army’s First Newspaper

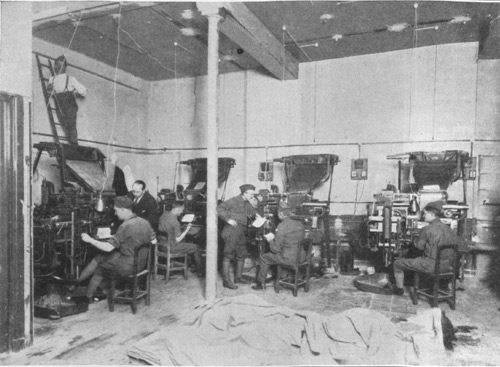

One hundred years ago today, on February 8, 1918, three U.S. Army privates turned out the first edition of Stars and Stripes, a military newspaper for soldiers in the American Expeditionary Force.

It was a new venture, hurriedly put together by the army, using a staff drawn from its pool of enlisted men. One of those first three privates was Harold Ross, a seasoned reporter who would later become the founder and editor of The New Yorker magazine. Another was famed sports writer Grantland Rice.

Another early member was Alexander Woollcott. He’d been the theater critic for the New York Times, but the army made him a war correspondent for the paper.

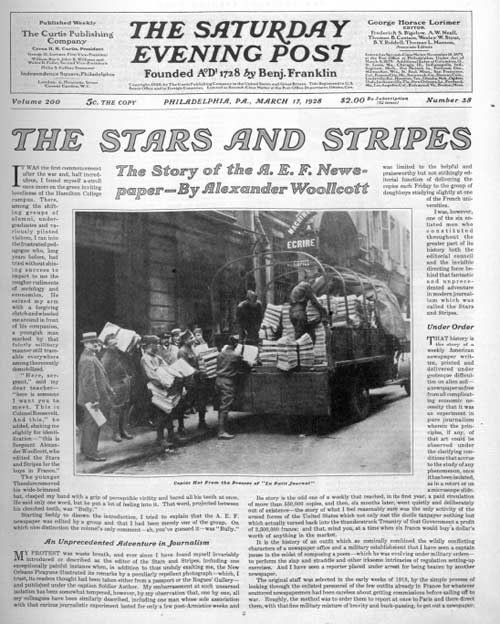

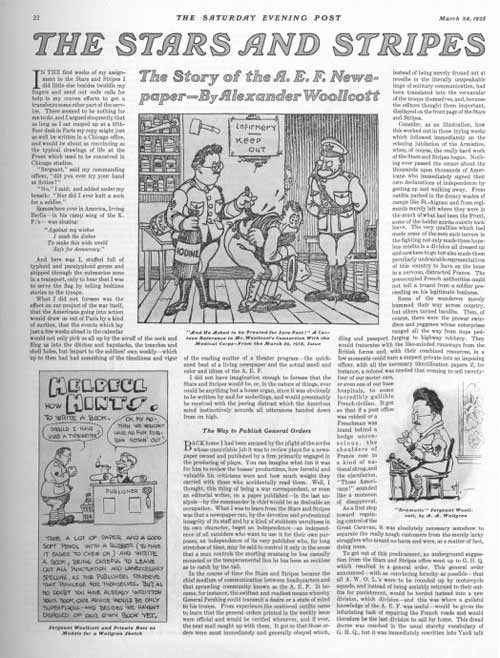

Ten years after Stars and Stripes’ first edition, Woollcott—who by then had become a notable member of the Algonquin Round Table—reminisced about his days at the paper in an article he wrote for The Saturday Evening Post on March 17 and 24, 1928. Of his first day there, he wrote, “there sat busily scribbling three of the strangest looking and, by strictly military standards, the least alarming soldiers I ever saw before or since.”

He was surprised at the paper’s success, assuming it “would presumably be received with the jeering distrust which the American mind instinctively accords all utterances handed down from on high.” However, in its first year of publication the weekly paper achieved a circulation of 550,000. It cost the soldiers ten cents (or fifty centime in French currency). So, not only did it not cost the American taxpayer a single dime, it turned in profits of about $500,000 to the Treasury Department when the war ended.

And it provided a critical service to the war effort. With troops scattered across the Western Front, communication was a challenge, as was Esprit de Corps. Soldiers wouldn’t have the faintest idea what the man in the next trench was up to, let alone his mates halfway across the country. Stars and Stripes allowed the A.E.F. to communicate the same message to all the troops, sharing important information with soldiers and creating a sense of unity in a chaotic environment.

The paper also proved handy for keeping soldiers in line. When the Army was having a problem with bored servicemen wandering away from their units and causing low-grade trouble in the French countryside as the war was ending, they asked the paper to publish a story claiming that all AWOL soldiers would be rounded up and required to repair French roads; they would be the last to be send home. Woollcott reported that “Within five days of publication 80 percent of the dare-devil absentees had tiptoed across France and contritely reported back to their outfits.”

Aside from managing the troops, Stars and Stripes also did its part to help war-torn France. Woollcott wrote:

I am…thinking especially of the windfall of francs that poured in when we started the notion that each outfit ought to adopt a French war orphan as its mascot, although that response took the hearty form of more than 2,000,000 francs in the first year, which sum—administered by the Red Cross—made things a little easier for some 3440 skinny, black-frocked kids who thereby got from their doughboy friends something even more lasting than the chewing gum for the sweet sake of which they swarmed around every detachment of American soldiers that put foot into a French village.

Stars and Stripes was revived for World War II and has been in publication ever since. Its reporters cover the experiences and concerns of G.I.s in their postings around the world.

The newspaper is very much alive today. Though authorized by the Defense Department, the paper maintains editorial independence and is published free of censorship or outside control. It’s unlikely, though, that the publication resembles Woollcott’s band of rollicking journalists taunting Germans, ducking bombs, and tweaking generals. He wrote, “I should like to say, in conclusion, that I never knew the staff of any newspaper who worked so hard or whose hours of ease were so hilarious.”

Featured image: from The Saturday Evening Post, March 17, 1928