A Voice From a Truly Violent Year

Journalist Lance Morrow once wrote that the day John Kennedy was killed was the day the U.S. stopped believing it could choose its destiny. Faced with a rising tide of violence, he argued, Americans came to accept the future was beyond their control.

That sense of powerlessness would only be strengthened by the killing sprees that have become more frequent over the years. Since Charles Whitman shot 14 students at the University of Texas at Austin 46 years ago, 22 other Americans have opened fire on strangers in restaurants, schools, and, most recently, a movie theater. From 1990 to 2000, there were four of these shooting sprees. There have been six in the past two years.

When viewed alongside the current wave of political hostilities and mistrust in the country, some Americans have been tempted into seeing an imminent collapse of society. Sooner or later, the thinking goes, this streak of violence in American society will push the country to some disastrous end.

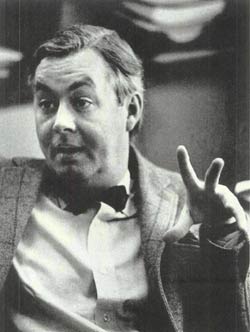

For perspective’s sake, we thought we’d offer some reflection on this subject from someone who lived in a truly violent and troubled year. In a Post article of 1968, Daniel Patrick Moynihan asked, “Has This Country Gone Mad?”

“Violence has rarely been altogether absent from American life… But I think the violence of this age is different: It is greater, more real, more personal, suffused throughout the society, associated with not one but a dozen issues and causes.

“The rise of black violence has been an… ominous and irrational turn… White terrorism against Negroes is an old and hideous aspect of American life, but… now it seems to be becoming a pastime for suburban housewives, taking target practice before television cameras, filling black silhouettes with white holes.

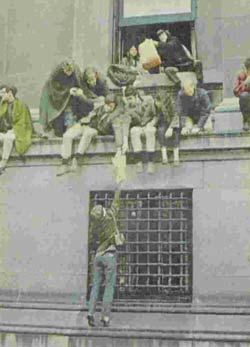

“Protest against war has been an old and honorable tradition in America, but with this war [in Vietnam] the peace movement itself has turned violent, threatening elected officials…

“One group after another appears to be withdrawing its consent from the agreements that have made us one of the most stable democracies in the history of the world.

“The espousal of violence, and violence itself, mount on every hand: private crime, organized crime; civil disorder at home to the point of insurrection, violence abroad on a scale unimagined.”

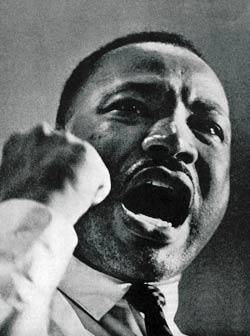

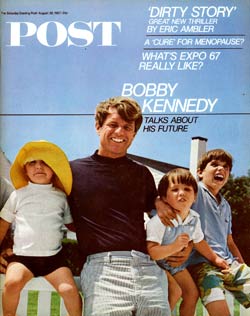

Keep in mind what was taking place as Moynihan was writing. In 1968, black militant activists were promoting violent resistance to white society. Black Panthers and policemen were trading shots in Oakland, Calif. The war in Vietnam was expanding: the Tet Offensive had brought enemy troops to the gates of the American Embassy in Saigon, and the U.S. began moving troops into Laos. Anti-war protestors became more militant; students took over Columbia University and rioted outside the Democratic convention. The murder of Martin Luther King Jr. and the subsequent riots were barely a month in the past. Just a few months later, Robert Kennedy would be assassinated while campaigning for the presidency.

In 2012, as the media reports (and sometimes promotes) messages of bitter social division, the separation between conservatives and liberals seem wider than ever before. But for all the bluster and threats, it still isn’t as great as in 1968. Back then, reactionaries and radicals were trying to overturn society, while a great number of Americans seemed willing to watch the collapse.

“A good many Americans do not hesitate to conclude from all this that American society is doomed, and they make no effort to conceal their great pleasure at this prospect. The ‘lust for apocalypse’… is something formidable to behold, especially in… the Ivy League radicals… [Meanwhile] Gov. George Wallace of Alabama… will have millions of Americans voting for him for President next fall… In East Harlem, a school official advises black children to get themselves guns and to practice using them. On silhouettes of suburban housewives, perhaps.

“Increasingly the nation exhibits the qualities of an individual going through a nervous breakdown. Is there anything to be done?”

Not a great deal, Moynihan answered, but a good beginning would be to abandon the myths that we could either control events or we were helpless. It would help, he said, if we “try to understand our collective strength as a people, and to try to see what is happening to that strength.

“The great power of the American nation…lies in our capacity to govern ourselves.

“Of the 123 members of the United Nations, there are fewer than a dozen that existed in 1914 and have not had their form of government changed by force since that time. We are one of those very fortunate few. More than luck is involved.”

What separated us from them was “the ability to live with one another.” America had been so brilliantly successful at this that we no longer appreciated it. It was time to remember what an accomplishment creative harmony was.

“An Englishman, an expert on guerrilla warfare, put it concisely to a Washington friend about a year ago. The visitor was asked why American efforts to impart the rudiments of orderly government seemed to have so little success in underdeveloped countries. ‘Elemental,’ came the reply, ‘You teach them all your techniques, give them all the machinery and manuals of operation… The more you do it, the more they become convinced and bitterly resentful… as they see it… you are deliberately withholding from them the one all-important secret that you have and they do not, and that is the knowledge of how to trust one another.”

This ability to trust, he continued, would not survive all the reckless talk about dissolution and despair. We shouldn’t come to accept civil hostilities and divisions as the natural state of America. “There must be a stop to this trend toward violence, and in particular, an immediate and passionate objection to any voice that gives aid and comfort to the present drift of events. That is almost a violent statement itself, but one surely warranted in the present state of the American republic.”