Still Flying: Superman Turns 80

The Man of Steel. Strange Visitor. The Man of Tomorrow. The Ultimate Immigrant. He is Superman, and his quest for Truth, Justice and the American Way turns 80 this month.

It’s easy to forget that there was a time when Superman was new. Before he exploded from the colorful pages of National Periodical Publications, he sparked into the minds of two young men from Ohio. School friends Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster met in 1928 and understood what it was like to be different. Both were Jewish children of immigrants, with Siegel’s parents having moved to America from Lithuania and Shuster born in Toronto to a Dutch father and Ukrainian mother.

Combining a mutual love of science fiction with their creative talents (Jerry wrote; Joe drew), they began to dream up characters that could find their way into the pulps and comics they themselves devoured. Some of those characters, like supernatural investigator Doctor Occult, stick around today. But nothing had the staying power of the refugee from Krypton, the first costumed super-hero.

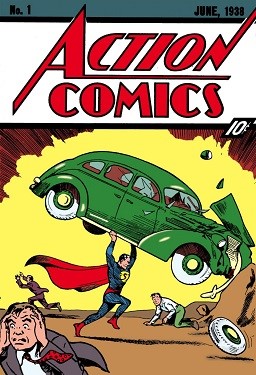

The duo pitched Superman to a number of syndicates and publishers before National finally bit. Their character commanded the June 1938 cover of Action Comics #1 with one of the most iconic images in popular culture. There he stood, lifting an automobile over his head as people fled and his cape flapped behind him. In no time, Action was selling more than a million copies a month; a veritable legion of costumed characters would follow in Superman’s wake, such as Batman, Wonder Woman, and thousands more.

Even with that early success, the formation of what we consider “Superman” today played out gradually. He didn’t fly at first, though his prodigious leaps made it into the opening narration of the subsequent radio and TV programs. His array of vision powers developed over time, as did the degree of his invulnerability and the measure of his strength. But the core of his character, the honesty and virtue, those were present immediately.

Kids and adults alike loved Superman because he was a hero that seemed to genuinely care about everyone. He didn’t just fight obvious criminals and monsters. In the early days, Superman was just as likely to tangle with a corrupt politician or an abuser as he was to fight alien robots and mad scientists. He rescued kittens from trees, helped out firefighters, and raced other heroes for charity. He represented the best in people.

Superman could also claim one of the best supporting casts in American entertainment. Tough-as-nails reporter Lois Lane was there right from the start, her appearance based on that of Joanne Carter, a model who later married Jerry Siegel. The radio program introduced blustery editor Perry White and Superman’s pal, Jimmy Olsen in 1940. The comics themselves presented an endless parade of mad invention, from arch-enemies like Lex Luthor and Brainiac to Superman’s cousin, Supergirl. We’d even meet his dog, Krypto.

Of course, as fantastic as the powers and the abilities and the cast were, nothing made Superman super quite as much as Clark Kent. Fans wanted to imitate the hero, but they empathized with his secret identity. Found and raised by honest, hard-working farmers Jonathan and Martha Kent, baby Kal-El learned his moral code in the American heartland. By the time that the young man realized the extent of his powers, his human parents had already done the work that would make him into a selfless protector of the weak.

People often wonder why Superman pretended to be Clark when he could be, well, Superman all the time. The key is in his values. When he puts on the cape and uses the heroic identity, Superman is still really just that ethical Kansas farm boy with a broader reach. It’s a sharp contrast to his friend Batman, where Bruce Wayne is just a mask that the Dark Knight hides behind.

As ComicBook.com columnist and Superman scholar Russell Burlingame puts it, “Superman endures in large part because of the simplicity that drives him: he intuitively understands what is right and just, and he acts accordingly, without hesitation. The darker, edgier, and more complex our pop culture heroes become, the more brightly Superman shines as a beacon to light the way.”

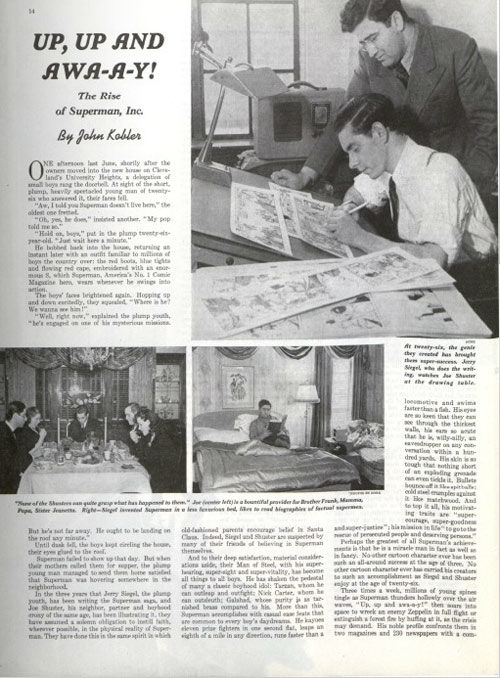

That shining beacon became even more important in the 1940s, as America watched the rise of Hitler in Europe. In June of 1941, The Saturday Evening Post gave readers a look into the early days of the growing allure of Superman in the article, “Up, up and Awa-a-y! The Rise of Superman, Inc.” Interviewing Siegel and Shuster, writer John Kobler attempted to get to the heart of Superman’s appeal. He wrote, “…Superman accomplishes with casual ease feats that are common to every boy’s daydreams.”

All of these various factors remain the engine that drives the popularity of Superman. He’s also proven to be incredibly adaptable to other media. Along with the radio show of the ‘40s and the Adventures of Superman television series of the ‘50s, Superman made deep impressions in movie serials, the influential Max Fleischer animated shorts, other made-for-television cartoons, and even on Broadway in It’s a Bird…It’s a Plane…It’s Superman.

It’s appropriate that the modern super-hero movie age truly began with Superman as well. Richard Donner’s 1978 Superman: The Movie made good on its tagline, “You will believe a man can fly.” Christopher Reeve’s portrayal synthesized everything we knew about Superman’s character, from his boyish charm to his clumsy Clark Kent to his righteous anger at Lex Luthor’s disregard for human life.

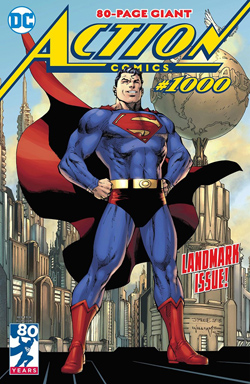

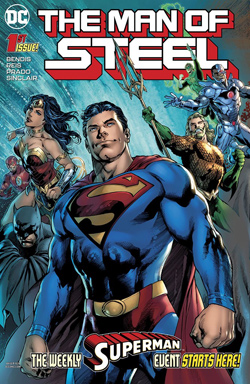

In April, Action Comics published its 1,000th issue. DC also launched a new, ongoing The Man of Steel title written by comics superstar Brian Michael Bendis (who himself was born in Cleveland). These books and other recent work by the likes of Dan Jurgens and Peter Tomasi have put the focus on a heroic, experienced Superman. He’s married to Lois these days, and their son Jonathan has his own adventures as Superboy (alongside best buddy, Robin) in the Super Sons comics.

For 80 years and counting, Superman continues to reflect what we consider to be the best of American values. He stands for the truth and justice. He’s about inclusiveness and acceptance. He, most simply, tries to make the wrong things right. Perhaps it’s no wonder that he continues to soar.

Happy Birthday, Superman!

Forget what you’ve read in the comics. Superman was not shot into space as an infant moments before his home planet exploded.

Instead, he was born in Cleveland, Ohio—specifically, in the halls of Glenville High School. And his parents were not Mr. and Mrs. Jor-L (original spelling), but Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster.

The mythical Superman, as we all know, was faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive (a dated figure of speech that reflects Superman’s age: 77 this month), and able to leap tall buildings in a single bound (before his creators decided he could, in fact, fly.)

The real Superman was a “continuity”—a recurring comic-book character with superhuman powers to create revenue. According to a 1941 article in the Post, the Man of Steel had risen from a long-shot character created by two unknowns to the most popular hero of his time—and the fictional hero market during the Depression was fairly crowded.

No other cartoon character ever has been such an all-around success at the age of three. No other cartoon character ever has carried his creators to such an accomplishment as Siegel and Shuster enjoy at the age of twenty-six.

His noble profile confronts them in two magazines [as comics were called then] and 230 newspapers with a combined circulation of nearly 25,000,000. That boy is growing rare who has no Superman dungarees in his wardrobe or no Superman Krypto-Raygun in his play chest.

When R. H. Macy & Co. staged a Superman exhibit in its New York store last Christmas, it took in $30,000 in thirty-cent admissions. Superman Day at the World’s Fair cracked all attendance records for any single children’s event, drawing 36,000 of them at ten cents a head.

Certificates, code cards, and buttons, setting them apart as members of the Superman Club of America, are proudly carried by some quarter of a million youngsters including Mickey Rooney, Spanky McFarland, Farina, a du Pont, a La Follette, Mayor La Guardia’s two children, and six Annapolis midshipmen.

Translations used to carry Superman all over Europe. But, banned wherever the swastika waves, he is now confined to the British Empire, the United States, Latin America (Super-hombre), Hawaii, and the Philippines.

Superman’s meteoric rise didn’t involve shooting a rocket-bound infant into space to eventually land on earth, but his existence was just as improbable given the two earthlings who invented him.

Co-creator Jerry Siegel was an extremely average student at Glenville High who worked to support his family.

At all leisure moments, however, he nurtured his ingrown soul on an undiluted diet of dime novels and comic strips, especially the Man-From-Mars category.

“It inspired me to devote myself henceforth to writing science fiction literature,” says Siegel, who often talks like that.

Presently he was devoting himself to it so wholeheartedly that it sometimes took two years to move him from one grade into the next.

One day in 1930, a classmate pointed Siegel toward another student with a similar interest in science fiction.

Siegel sought him out. “I understand,” he said, “that you draw science fiction stuff.”

“Uh-huh,” Shuster admitted, his eyes blinking behind double-thick lenses.

[Soon] they were breathlessly discussing Buck Rogers, Tarzan of the Apes, and other exemplars of the contemporary comic strip.

By the noon recess the boys had formed a partnership which has progressed, unmarred by a single dispute, to this day.

For the next six years, Siegel and Shuster turned out several ideas, none of which took them far.

The partners brewed many a strong potion—Doctor Occult, a sort of astral Nick Carter who kept tangling with zombies, werewolves, and such; Henri Duval, a doughty musketeer in the image of D’Artagnan—but no editor hastened to press riches on them.

It was on a hot night in 1932 that Siegel got his best idea: a character who incorporated the strength of every fictional hero he knew. He worked through the night to write a complete story line.

As the dawn rose over Cleveland, Siegel, shirttail flying and script clutched in his fevered hands, raced through the empty streets to the Shuster home—one of the few violent exertions he has ever permitted himself—and roused his partner. Shuster took fire at once. Without pausing for either food or rest, they spent the rest of the day polishing off the first twelve Superman strips.

The idea was turned down by every syndicate and comic-magazine they contacted—sometimes two or three times—before a printer took a chance on these unknowns. By the third issue, Superman’s sales were up, up, and- well, you know the rest.

Unfortunately, the publisher required Siegel and Shuster to sign a release form giving him all rights to the character.

The partners, who by this time had abandoned hope that Superman would amount to much, mulled this over gloomily. Then Siegel shrugged, “Well, at least this way we’ll see him in print.” They signed the form.

For years afterward, the two struggled for a more equitable part of the Superman fortune. Yet they continued to produce Superman comics; even if they were disappointed in their business arrangement, they never lost faith in the character they created. Their readers rewarded their dedication with their own, creating such enraptured fans as this British boy observed by an American reporter.

Touring London’s bomb shelters during a heavy raid, he observed a cockney boy immersed in the pages of Superman. Neither the din of antiaircraft fire nor shells exploding nearby could distract his attention, and in his rapture he began squirming and jostling his neighbors. After a particularly violent detonation, his mother snatched the magazine out of his hands. “Give over,” she bawled, “and pay attention to the air raid.”