Happy Birthday, Jeeves

This year marks the 100th birthday of one of the greatest creations in Western literature. It was in 1915 that a fictional character uttered those legendary words: “Mrs. Gregson to see you, sir.”

Well, if the words weren’t legendary, the character that spoke them was destined to be. For this was the first sentence uttered by a British valet named Jeeves, first name possibly Reginald.

He was the creation of humorous British storyteller P.G. Wodehouse, born today (October 15) in 1881.

Just as British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle created the literary duo of Sherlock and Watson, Wodehouse too created a team of perfectly counterweighted characters: the impeccable, always correct, perfectly tactful valet Jeeves. Opposite him, Bertie Wooster, a wealthy and witless young man. In every Jeeves-and-Wooster tale, Bertie gets himself into trouble with friends and family. And Jeeves comes to his rescue, engineering a happy ending with a few well-placed words and judicious actions.

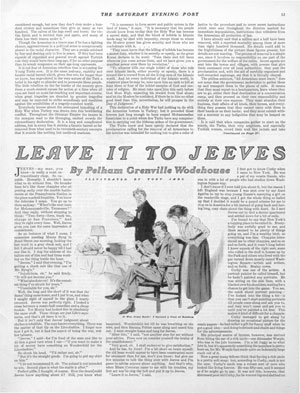

Jeeves first came to America’s attention in September 1915 when the Post published Wodehouse’s “Extricating Young Gussie.” In this tale, Jeeves does little but act the role of a conventional British valet, displaying none of his understated wit or problem-solving genius. But Wodehouse must have recognized the comedic potential because he soon wrote another story that allowed the valet to display his skills; “Leave It to Jeeves” appeared in the Post on February 5, 1916.

Jeeves proved invaluable to Wooster, saving his employer from the consequences of foolishness through some 30 short stories and 11 novels. Jeeves also served Wodehouse particularly well as a reliable character for 59 years. The discreet and all-knowing servant continues to serve as a stock character in books, plays, and movies today. The author of Downton Abbey, for example, split him into two characters: the stiff, propriety-conscious butler Mr. Carson and the deft-with–a-lint-brush–or-word-of-advice valet Mr. Bates.

The best way to appreciate the genius of Jeeves, however, is to read him in action. On the centennial of his first appearance in print (and in illustration), we can’t think of a better choice.