How Tarzan’s Author Did It All Wrong, and Got It Right

You’re working on the Great American Novel, and following all the best advice to new writers. You read widely from the great books. You study the rules of grammar and effective composition. You write about what you know. You write, revise, and write more. And you’re prepared to endure years of obscurity before your work gets popular.

Of course, you can completely ignore all these rules and still succeed. Edgar Rice Burroughs proved it. Without trying, he broke nearly every conventional rule for achieving literary success. He didn’t study composition or do much practice writing. He didn’t read widely. He didn’t even want to be an author.

Burroughs grew up with dreams of a military career, but when he applied to West Point, he failed the entrance exam. He enlisted in the army but was soon discharged for medical problems. For years, he drifted between jobs, selling cattle, managing an office, running a store, and mining for gold among other unsuccessful endeavors. He only started writing magazine fiction because he was desperate to earn a little money.

In 1911, he submitted an adventure story about life on Mars to All-Story, a pulp magazine. When it was accepted, he turned out two more in the same vein. And then he wrote Tarzan of the Apes.

Rather than writing about what he knew, Burroughs set his adventure-fantasy in Africa, a continent he only knew from a single book he’d read. Yet his ignorance of the country didn’t reduce the story’s appeal when it was published in 1912.

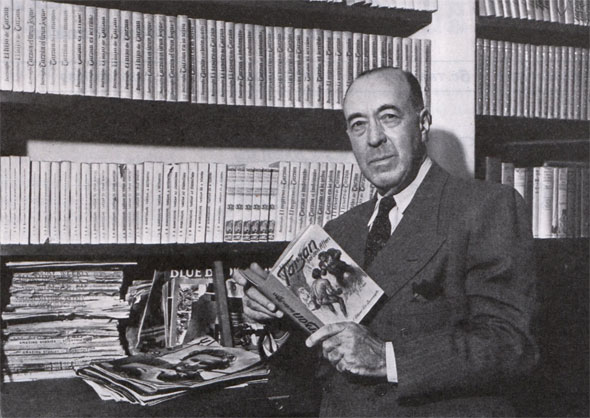

Burroughs soon followed up on his jungle hero with The Return of Tarzan. Before his death in 1950, he published 22 more titles in the Tarzan series. Between these books, he also wrote over 45 other novels, most of them set in outer space or the Wild West. They helped make Burroughs a wealthy man, but they were never as successful as the Tarzan series.

Burroughs began to exploit the public’s enthusiasm for his jungle hero despite the advice of experts. They warned him that he would over-market his character and the public would tire of Tarzan. But Burroughs ignored them and licensed his character for simultaneous use in comic strips, movies, and merchandise. Once again, he proved the experts wrong. Instead of diluting the appeal, mass-marketing Tarzan only made the character even more popular.

We’ve come a long way since Tarzan was the most popular hero of the day. Other characters have arisen to crowd him off the center stage of popular culture. This year, as he turns 113 years old, he probably wouldn’t seem impressive if you stood him in a lineup with today’s superheroes. But don’t let his lack of cape and skin-tight costume fool you. Modern superheroes, and their creators, owe their livelihood to Tarzan. He was a major turning point in popular fiction, and he made a new generation of do-gooders possible.

Before his time, the heroes in adventure novels were drawn from an established cast of chivalrous characters. They might be noble cowboys or soldiers, but just as often they were roguish characters who lived on the edge of society: outlaws, pirates, or detectives. But all heroes, if they existed on planet Earth, had to fight the usual villains with conventional weapons. Adventure stories had to stay within the fictional boundaries that readers knew.

Tarzan changed the rules for heroes just as Burroughs changed the rules for writing bestsellers. His jungle hero wasn’t limited to traditional strength. Raised by apes, Tarzan had developed incredible power. He could fight all manner of dangerous animals, including fantastic creatures and dinosaurs.

His African locale also opened new possibilities for villains. Tarzan fought slave traders (Tarzan Triumphant), mad scientists (Tarzan and the Lion Man), communist plunderers (Tarzan the Invincible), homicidal cult (Tarzan and the Leopard Men), and German soldiers in World War I (Tarzan the Untamed). And in a creative leap that better writers might have advised against, Burroughs dropped him into forgotten colonies of people lost in time, so he could fight medieval knights (Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle) and Roman gladiators (Tarzan and the Lost Empire).

As long as he was rewriting the rules, Burroughs could expand the realm of the possible. He made Tarzan implausibly smart. For example, Tarzan taught himself to read English from a book, even though no one had ever explained what a book was. In fact, he hadn’t even heard human speech when he learned to read. But then, there had never been a hero like Tarzan. And once readers got pulled into the book, they wouldn’t stumble over such impossibilities.

Burroughs’ great hero may have faded into the background of popular characters, but he is never forgotten. The character has appeared in about 100 motion pictures, not counting the several Tarzan television programs. No doubt there’ll be another Tarzan movie in the future. Perhaps it could be another Disney animated feature; the director of the wildly popular Frozen recently declared that Tarzan was the brother of his movie’s main characters.

Modern readers who pick up a Tarzan book for the first time might find Burroughs’ style a little dated. But he may also note the similarity between Burroughs’ hero and another orphan who grew up to wage a solitary, unbound-by-rules war on evil. The resemblance isn’t coincidence: Without Tarzan, there could be no Batman.