Edgar Rice Burroughs on How to Become a Great Writer

This article was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post on July 29, 1939.

Is any other town in America named for a character in fiction?

Everybody sooner or later turns out to be a writer. Get deep enough into anybody’s confidence, and you find that he has manuscripts. Psychoanalysts build a false science on the theory that millions of people are maladjusted lovers; a better knowledge of the world would teach that they are maladjusted writers.

David Binney Putnam launched himself on a serious literary career by wearing overalls, growing a beard and setting out to get the life stories of derelicts; the first derelict he met was a writer who took out a notebook and insisted on having young Putnam’s life story.

Harold Ross, editor of The New Yorker, finding himself sick of New York City’s 7,300,000 writers, tried to hunt a spot where there were no writers. He and Harpo Marx drove a car far into the Rockies. En route Harpo turned out to be a secret writer. The car broke down. The editor followed a trail leading to a cabin in a lonely mountain valley. In the cabin he found a writer writing a novel.

All this shows that, as Ed Howe put it, the people are smart. They are on the right trail. Writing is the shortest cut to affluence except inheriting big money. Today is the harvest time for writers, and tomorrow’s prospect is still better. A sure-hit writer can get $5,000 a week and upwards in Hollywood. A good radio-script man or woman is worth four figures a week. Magazine editors and book publishers go out in posses after any promising writer. Writing is the royal road to statesmanship; there is an enormous demand on the part of public men in Washington and elsewhere for artists in the oration-writing department of belles-lettres. Television holds a promise of becoming a writers’ paradise; if it is a success it will require legions of writers to feed the television studios with scripts.

The paradox of the literary situation is that, while everybody is a writer, there is a shortage of writers for the thousand-a-week spots and the five-thousand-a-week spots. According to Pandro Berman, head of the RKO picture studio, Hollywood can’t get one tenth of the good writers it needs. His solution of the problem is for the universities to stop concentrating on the second-rate professions, which are already overcrowded, and to devote themselves to turning out big-money master writers, who are needed by the thousands. Law, medicine, engineering and the sciences have proved themselves to be excellent stopgaps and steppingstones for writers, but the demand of the time is for direct literary training which will enable young men and women to assume the thousand-a-week burdens immediately on graduation.

The main difficulty with Berman’s suggestion is that of organizing the courses. Nobody seems to have worked out a satisfactory method of training writers to write. Colleges are good on punctuation marks, but not on what to put between them. Famous writers seem to have left few hints that are useful to beginners. Ring Lardner said it was a matter of selecting pencils of the right colors. Anthony Trollope said it was a matter of attaching the writer’s pants to the chair with beeswax. Goethe attributed his output to a chair in which it was impossible to get into a restful position. In the vast literature about Dr. Samuel Johnson, only one practical rule of writing is to be found, and Doctor Johnson had that from an old schoolmaster; the rule being that, if you think any sentence you write is particularly good, strike it out. Dickens picked up his technique by accident. As a Parliamentary shorthand reporter during the decadence of parliamentary oratory, he learned the comic effect of presenting trivialities in ornate and sounding prose.

Tests of Greatness

The subject has to be simplified before the universities cap turn out prose masters on belt conveyors. A new approach to the problem would be to take the greatest living writer and make a thorough analysis of the factors, which caused his greatness. Because of differences of opinion as to who is the greatest living writer, it is necessary to adopt arbitrary tests to identify him.

These tests are:

- The size of the writer’s public.

- His success in establishing a character in the consciousness of the world.

- The probability of his being read by posterity.

Judged by these tests, Edgar Rice Burroughs is first and the rest nowhere.

No other literary creation of this century has a following like Tarzan. Another character with a worldwide public is Mickey Mouse, but he belongs to a different art. The only other recent works of imagination in this class are Charlie McCarthy and The Lone Ranger, but their vogue is confined to the English-speaking peoples and they are still novelties rather than assured immortals.

Twenty-five million copies of the Tarzan books have been sold. Taman has established his durability; the first book on the ape boy came out a quarter of a century ago, and he is today more popular than ever. A writer’s foreign following has been described as a contemporary posterity; Tarzan books have been translated into fifty-six languages and dialects. Hundreds of baseball players, football players, wrestlers, fighters and other athletes are nicknamed Tarzan. Extra-large schoolboys are called Tarzan in admiration, and undersized ones are called Tarzan in derision. Sherlock Holmes, Peter Pan, Pollyanna and Babbitt are perhaps the only literary creations of the last fifty years whose names are rooted in the English language as strongly as Tarzan; and Tarzan is a household word on every continent and on the larger islands from Iceland to Java.

Tarzan is a pillar of the American fiscal system. Through his author, his motion-picture company, his cartoon-strip syndicate, his radio sponsors and his various other concessionaires, the African ape boy contributes enough in taxes to pay the salaries of most of the United States senators.

What Makes Him Click

Burroughs is clearly the man to tell the 130,000,000 American writers how to write. His life story ought to be the supreme textbook. The main rules for literary training that can be gathered from the experiences of Burroughs are:

- Be a disappointed man.

- Achieve no success at anything you touch.

- Lead an unbearably drab and uninteresting life.

- Hate civilization.

- Learn no grammar.

- Read little.

- Write nothing.

- Have an ordinary mind and commonplace tastes, approximating those of the great reading public.

- Avoid subjects that you know about.

Burroughs had been an ill-paid employee and an unsuccessful small businessman for fifteen years before he wrote a word of fiction. The great difficulty in basing a college training on his rules is that of compressing into four years all the dullness, wretchedness and futility which it took Burroughs fifteen years to assimilate.

Burroughs started at twenty as a cattle drover and then became an employee on a gold dredge in Oregon. For a time he was a railroad policeman in Salt Lake City. He put in stretches as an accountant, as a clerk and as a peddler. His most important position was that of head of the stenographic department of Sears-Roebuck, in Chicago. A docile employee, he was never fired. An inveterate reader of help-wanted ads, he was constantly obtaining new positions not quite equal to his old ones. Added to that, he was always ready to join his own pennilessness to the pennilessness of some other man, and to found a partnership on any naïve dream of avarice.

King of the Pot-and-Pan Trade

Combining their resources of no capital, no experience and no contacts, Burroughs and a partner founded an advertising agency, which failed. Having no experience with salesmanship beyond that of being repulsed by housewives when he tried to sell sets of Stoddard’s Lectures, Burroughs wrote a correspondence course in salesmanship. After studying by correspondence for a few weeks, his students were to be graduated into fieldwork. Small stocks of aluminum pots and pans were sent to them with instructions to sell them from door to door and remit the money to the home office.

Burroughs and his partner thought there were millions in it. They regarded themselves as aluminum kings about to corner the pot-and-pan trade with the help of peddlers who would pay tuition fees for the privilege of peddling. But the students all quit when they got to the fieldwork stage. Some failed to send back either the money or the pots and pans.

The Burroughs family had been rich when Edgar was a boy, but had lost its money. His allowance at prep-school had been $150 a month. During his entire business career he never earned as much as his prep-school allowance. Twice he was compelled to pawn his family heirlooms in order to buy food for his wife and children. His failure as a businessman was so complete that he was reduced to earning a living by writing hints on how to become a successful businessman.

The businessman’s bible three decades ago was System, the Magazine of Efficiency. It was a pioneer in introducing charts and graphs. Many businessmen worshiped charts and graphs as religious symbols. It was their belief that, if they stared long enough at these mystic curves and angles, red ink would turn into black.

A new department was introduced by the magazine. On payment of fifty dollars a year, a businessman could write to the magazine as often as he liked, and receive detailed advice on his business problems. Burroughs was hired to give the detailed advice. There was also a detailed-advice department for bankers, which was handled by a youth of twenty-one years. Burroughs sat at his desk from morning until night, writing counsel to merchant princes and captains. He used words that rumbled with portentous business wisdom, but were too vague to enable any industrial baron to net on them. Burroughs had a conscience, and it was always his fear that, if his advice ever became understandable, it would land his clients in the bankruptcy courts. With his letters he would enclose some of the awe-inspiring hieroglyphics now known as “barometrics.”

Burroughs’ advice never brought a complaint, and he may have been as good as anybody else in this field. Nothing is definitely known on the subject today except that the more the charts and graphs flourish, the faster business decays.

Burroughs’ first contact with literature came in 1911 through his connection with Alcola, a cure for alcoholism. Alcola cured alcoholism all right, but the Federal Pure Food and Drug people took the position that there were worse things than alcoholism, and forbade the sale of Alcola.

One of Burroughs’ duties in the Alcola firm was that of putting advertisements in the pulp fiction magazines. He bought the magazines in order to make sure that his ads were printed. He detested fiction, but when he looked at the ads some of the reading matter entered his field of vision. His reaction was approximately that of Dean Swift, who, under similar circumstances, exclaimed, “No man alive ever writ such damned stuff.”

His next thought was that, if this was literature, any man could be a man of letters if he would abandon his mind to it. He wrote a novel. Thomas Newell Metcalf, editor of the All-Story Magazine, accepted it and sent Burroughs a check for $400. It was published as a serial in All-Story in 1912, under the title of Under the Moon of Mars.

Metcalf wanted to make a Sir Walter Scott out of Burroughs. He induced him to spend months of research on the Wars of the Roses. The result was a novel entitled The Outlaw of Torn. Metcalf rejected it.

Burroughs saw the folly of research. He had located his first novel on Mars because nobody knew the local color of that planet or the psychology of the Martians, and nobody could check up on him. A similar motive influenced him partly in writing his first Tarzan book, Tarzan of the Apes. He created a new race of apes, bigger than gorillas, and placed them in an unknown part of Africa. He knew that nobody could trip him up on the psychology, customs and language of his own private anthropoids.

For African local color he read Stanley’s In Darkest Africa. He got his flora all right, but he made a blunder in his fauna. One of his important characters was Sabor, the tiger. There are no tigers in Africa. Letters from readers were printed in All-Story on this point. A man in Johannesburg confounded the critics, however, by writing that everybody in Africa referred to leopards as tigers. Nevertheless, Burroughs later changed Sabor to a lioness. He got a check for $700 from All-Story for Tarzan of the Apes.

Burroughs had by this time retired from his last business, that of selling a pencil sharpener, and was devoting all his time to writing. His business career had, by its dreary futility, been a genuine literary apprenticeship. During his last few years in commercial pursuits, life had become almost intolerable to him.

He was too poverty-stricken to pay for any of the tired businessman’s relaxations, but he hit upon a free method of making himself feel better. When he went to bed he would lie awake, telling himself stories. His dislike of civilization caused him frequently to pick localities in distant parts of the solar system. Every night he had his one crowded hour of glorious life. Creating noble characters and diabolical monsters, he made them fight in cockpits in the center of the earth or in distant astronomical regions. The duller the day at the office the weirder his nightly adventures. His waking nightmares became long-drawn-out action serials.

The Delirium Road to Success

Psychiatrists consider these reverie addicts as borderline cases. If Burroughs’ family had known of his mental state, they would have called in a medical man, who would have probably insisted on having his teeth out, according to the fashionable method of treating such patients in 1911. Twenty years later, Burroughs would have been advised to save up his money for a few years and go to a psychoanalyst, who would have cured him of an incipient $10,000,000 affliction. A raise of twenty-five dollars a month in 1911, according to Burroughs’ estimate, would have made him happy and caused him to put in nights of sound, refreshing slumber, instead of constructing penny-dreadful deliriums for himself.

Burroughs had given away serials to himself for five years or more before he learned that he could sell them. He had become a master of the slaughterhouse branches of fiction. It is clear from reading the Tarzan and other Burroughs books that he devoted little of his twilight sleep to tea-table and boy-meets-girl imbroglios.

Five years of dark and bloody mysteries gave his pen a high professionalism in pyramiding climaxes and piling up horror; but he was an awkward novice when the structure of his novel required him to introduce scenes of society life or hearts-and-flowers passages. Burroughs is great when Tarzan has a half nelson on a lion or a gorilla, but he has no talent for drawing-room hubble-bubble or boudoir hanky-panky. There is a trace of Homer in him, but not any Noel Coward.

In Tarzan of the Apes the reader can put his finger on the passages where Burroughs is the dream-disciplined artist and on the passages where he is the self-conscious amateur. He wanted to endow his ape-reared infant with a magnificent heredity. He was under the impression that the way to have a glorious moral, mental and physical inheritance was to be a scion of the British aristocracy. So Tarzan’s parents were Lord and Lady Greystoke, the flower of the old nobility. Burroughs created them out of condescending sawdust.

It is obvious that Burroughs in his nightly trances had wasted no time messing around with lords and ladies. The Burroughs noblemen cause the reader to turn instinctively to P. G. Wodehouse for a sympathetic picture of the British aristocracy. But when the real Burroughs gets to work on his wild boy, his colossal anthropoids, his giant carnivora and his cannibals, it is not difficult to see why 3,000,000 copies of Tarzan of the Apes have been sold and why Tarzan is the best-known literary character of the twentieth century.

Burroughs says that his ordinariness explains his success. When he wrote his first novel for All-Story, he used the nom de plume of Normal Bean, meaning common head. By accident the editor changed it to Norman Bean. Burroughs was unwilling to use his own name at the time because he thought it would hurt his standing in the unsuccessful business world. He believes today that his novels are in demand because the things that interest him are bound to interest the ordinary Undoubtedly a certain galloping commonplaceness is one of his assets, but he has others. He did not win his world public solely through mediocrity. There are pages of his books which have the authentic flash and sting of story telling genius.

One brilliant passage is that in which the half-grown Tarzan identifies himself as the being who is reflected in a pool of water. Tarzan had already had reason to suspect that he was not a trueborn ape. Gazing at himself in the waters, he discovers what a poor relation of the higher anthropoids he really is. Burroughs is in a high literary vein when he describes the boy’s chagrin in comparing his parody of a countenance with the pretentious physiognomies of his playmates. Instead of nostrils that spread half across his face, he had a despicable imitation of an organ of smell. He had trifling bits of ivory where competent tusks should have been. Self-pity overwhelmed him when he discovered that his eyes were an insipid gray instead of being big, black and blofldshot. On realizing that he was hairless like a snake, he plastered himself from head to foot with mud.

Tarzan had already suspected that he was not a true ape, because he had discovered in a deserted cabin a number of kindergarten books with pictures of animals. He had begun to fear that he resembled the apes less than he resembled another animal, whose picture was always printed with what appeared to be three little bugs — B, O, and Y. The painful conviction was forced upon him that he was a B-O-Y.

Using these three bugs as a clue, Tarzan works out the secret of all the twenty-six bugs in the alphabet. He learns written English without knowing how to pronounce it. Burroughs’ handling of Tarzan’s self-education is better than the cipher sequences in The Gold Bug or The Dancing Men.

Tarzan’s discovery that he is a member of the human species later lands him in a beautiful ethical dilemma. Having killed an African tribesman, Tarzan is about to help himself. Certain doubts assail him. His bringing up had taught him that eating a member of one’s own species was not done. He has eaten raw gorilla, but the gorilla does not belong to his set. Tarzan now knows himself to be a man, and he recognizes the dead African as a man. On the other hand, Tarzan is hungry, and his political sympathies are all with the apes. It is a pretty case of conscience, and Burroughs does justice to it. In the end Tarzan takes the high ethical stand and never refreshes himself with an African.

Tarzan Gets Slapped

One sequence in Tarzan of the Apes will bear comparison with the much admired passage in Gulliver’s Travels in which the Lilliputians, in an official report on the effects removed from Gulliver’s pockets, suggest that his watch is his god because of the frequency with which he consults it. Tarzan sees Kulonga, son of a savage chief, cook a wild boar and eat it. Tarzan knows fire only as Ara, the lightning. He cannot understand why anybody would spoil raw meat by plunging it into fire. He concludes that Kulonga is a friend of the god of lightning and is sharing the wild boar with him. There is occasionally a touch of poetry in Burroughs, as in describing Tarzan’s grass-woven lasso as “his long arm of many grasses.”

Another source of the author’s strength is his strong grip of character. Not only Tarzan but the apes and animals are highly individualized beings who seldom step out of character. Burroughs edits the Tarzan movies and newspaper strips to see that no liberties are taken with the Tarzan psychology. In one movie scene, for example, Tarzan threw his head back and laughed long and boisterously. “Strike it out,” ordered Burroughs. Tarzan, in spite of his violent activity, is as reserved and contemplative as Hamlet. Nothing could be farther from his personality than brainless uproariousness.

One of the handsome passages in Tarzan of the Apes is the ape-bred boy’s first encounter with white womanhood. Tarzan rescued the heroine, a glamorous but educated American girl, from the clutches of a mate-hunting giant ape. The bronzed and sun-baked Tarzan, accustomed to seeing none but ape women and blacks, was conscious of a sudden prejudice in her favor, in spite of her white body. He wanted her to know that he was favorably disposed toward her. His good will took the form of pawing and nuzzling. She slapped him. Tarzan was astonished. He had assumed that, when a member of a species showed a nice spirit toward another member of the same species, that spirit would be reciprocated. He could not understand why she was returning evil for good.

The Boy Who Escaped Grammar

Burroughs was told that Kipling liked Tarzan and supposed that Tarzan was patterned after Mowgli of The Jungle Book. According to Burroughs, Taman is a literary descendant, not of Mowgli but of Romulus and Remus, who got such a raising from a she-wolf that they founded Rome. Burroughs credits himself with only one stroke of genius—the naming of Tarzan. The impact of those two syllables on the eardrum is, in his opinion, largely responsible for the world success of the Tarzan books. This is one of the few literary secrets of Burroughs that is communicable. In christening his characters he works with syllables as some composers work with musical notes. He tests one sound against another until, after trying perhaps hundreds of combinations, he has a name that rings like a fire bell.

The early life of Burroughs was more interesting than his business career, but it furnishes few hints toward becoming a great writer. His father, who had been a major in the Civil War, grew rich in the distilling business. Later he became a manufacturer of electrical batteries. He had a habit of reading aloud, which partly caused young Edgar’s aversion to literature. When, for example, his father read Dombey and Son, Edgar hated Dombey and had the impression that Dombey and Dickens were one and the same person. When he learned the difference,it was too late for him to overcome his ingrained prejudice against Dickens. He has also cherished a lifelong dislike for Shakespeare, but is big enough to state that he assumes it to be his fault rather than the poet’s.

Burroughs’ escape from grammar was a lucky accident. He was sent first to a private school in Chicago which held that the teaching of English grammar was nonsense and that students should absorb grammar through Latin and Greek. Edgar absorbed no Latin and Greek. He was then sent to Phillips Andover, which, assuming that all freshmen were thoroughly drilled in grammar, ignored that subject. Phillips Andover quickly waived on young Burroughs, and he was sent to military academy, which paid no attention to grammar. Edgar thus became an uninhibited writer, free from the anxieties about moods and tenses which kill spontaneity. Burroughs doesn’t know whether he is grammatical or not, and cares less. He always writes or dictates at top speed in order to get his thoughts on paper while they are fresh and hot. No grammar-scared writer can do that. Burroughs never makes corrections unless he finds an inconsistency in his development of plot.

The battery business led the elder Burroughs to become interested in an electrical horseless carriage. Edgar demonstrated it at the World’s Fair, in 1893. The only time he ever felt that he amounted to something was when he drove a nine-seater horseless surrey about the fairgrounds, starting runaways every hundred feet or so.

A Youthful Glory Seeker

In his youth Burroughs had a craving for glory. He preferred the military variety because his father had been a soldier. After graduating from the Michigan Military Academy he joined its faculty as a cavalry instructor. After the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5, China, which had been defeated because her armament consisted largely of drums and dragon banners, started to reorganize her army. Burroughs sought a commission in the Chinese army, but failed. Later he obtained a commission in the Nicaraguan army, but his family interfered. At the age of twenty he enlisted in the Seventh Cavalry and was sent to Arizona against Geronimo. Instead of cavalry charges, however, the campaign consisted mainly of ditch-digging. Wires were pulled, and, because Burroughs had enlisted while under age, he was discharged. In 1898 he volunteered for the Rough Riders, but received a polite letter of regret from Theodore Roosevelt.

During his brief Regular Army service, Burroughs had committed two grave infractions of the military code. On sentry duty, he was required to shoot to kill if anyone disregarded his warning of “Halt, or I fire.” His warning was twice disregarded, but Burroughs did not shoot. In each case he wrongfully saved the life of a drunken member of his own outfit. He escaped disgrace, his unsoldierly conduct never becoming known.

From the Army Burroughs went directly into cow handling, and then into gold dredging. Years later, after establishing himself as a writer about imaginary worlds and countries, he wrote The Bandit of Hell’s Bend, based on his Western experience. This was a violation of his custom of not writing things personally known to him; but things personally known to him; but Alexander Grosset, of the publishing house of Grosset and Dunlap, pronounced The Bandit of Hell’s Bend the greatest Western ever written.

The old craving for glory was roused in Burroughs only once after the Spanish-American War. He happened to see the regal state in which the president of the Oregon Short Line traveled. He took the only railroad job he could get. In hot pursuit of glory, Burroughs chased bums out of boxcars in the Salt Lake City railroad yards for six months. But the idea of becoming a railroad president—last of his high ambitions—faded, and he drifted into the business career which punished him until he took refuge in literature.

The first Tarzan story did not immediately make Burroughs rich. The idea of bringing it out in book form was rejected by publishing houses, one reason being that they felt that the title, Tarzan of the Apes, would shock refined people. Burroughs wrote a sequel, The Return of Tarzan. It was declined by the Munsey publications, without the knowledge of Bob Davis, editor-in-chief of that organization.

Davis was furious when the Tarzan sequel was printed in a rival magazine. The famous editor took Burroughs under his wing and insisted on publishing everything he wrote. Even Davis, however, did not see the future of Tarzan. He induced Burroughs to cause the original Tarzan to assume his title of Lord Greystoke and take his seat in the House of Lords, while the series was carried on with the son of Tarzan. This caused confusion, and Burroughs finally went back to Tarzan the First. According to rigid rules of biology, the African wild boy is now a grandfather.

In less than, a year after his first work was published, Burroughs was a big pulp name and a ten-cents-a-word writer. As his literary labor consisted largely of transcribing from memory the old phantasmagorias with which he soothed himself during his business life, his production was large. He was making more than $20,000 a year before his first book was published. On his banner day he wrote 9100 words— $910 worth.

An International Institution

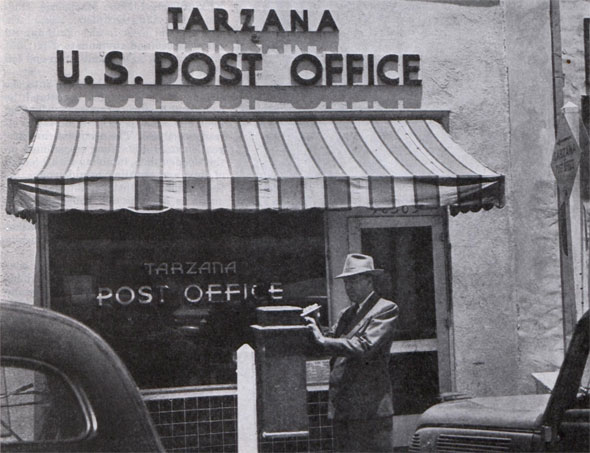

Big money did not immediately soften Burroughs’ hatred of modern life. His great aim was to escape from civilization, and, as soon as he had money, he went to Southern California. In 1919, after he had become wealthy, Burroughs bought the 600-acre Harrison Gray Otis ranch in the San Fernando Valley and founded the town of Tarzana, about half an hour’s auto ride from Hollywood. He delighted to ride, stetson on head, gun across saddle, over his hills and through his valleys and his canyons.

He started to ranch on a large scale with pedigreed animals. It was necessary to write furiously to support the ranch. Scarcity of wells and springs was the trouble. Water had to be brought in from the outside. After some experience with water rates, he found it would be cheaper to take his cattle to a soda fountain. The ranch was turned over to the El Caballero Golf Club, which failed. After running it as a public golf course for a while, Burroughs sold out.

Burroughs had been writing four years before a publishing house would take a chance on printing his novels in book form. The late J. H. Tennant, editor of the New York Evening World, had read Tarzan of the Apes in All-Story and bought the right to print it in his newspaper. Other papers followed suit, and Tarzan fans became an important bloc in the community. A. C. McClurg .& Co., one of the many publishers which had previously rejected Tarzan of the Apes, began publishing the Tarzan books and then other Burroughs novels. Millions of boys took to leaping from limb to limb and from tree to tree. The nation resounded with the Tarzan yell and the snapping of collarbones.

Today Burroughs has forty nine books in print. The sales have exceeded 30,000,000 copies. The Tarzan books are still in great demand in nearly every part of the world except Germany. In 1925 Burroughs was taking more royalties out of Germany than any foreign author, but in that year a German writer printed a book entitled Tarzan the German Devourer. During the World War, Burroughs had, in Tarzan the Untamed, caused Tarzan to do his bit by capturing German officers and feeding them to lions. The sensitive Teutons boycotted Burroughs after 1925.

Tarzan is a radio star today. The Tarzan comic strip is printed in about 150 American newspapers and forty foreign ones, including journals in Java and Ceylon. Tarzan has been a great money-maker in the movies for more than twenty years. Johnny Weissmuller is the ninth actor to play the part in the films.

Tarzan’s importance in the films increased greatly in 1932, when the late Irving Thalberg took charge of his career. Thalberg and Burroughs agreed that Tarzan pictures should be great spectacles and should come out once a year, like a circus. Thalberg’s first two pictures cost more than a million each, and the third, Tarzan Escapes, cost more than a million and a half. After Thalberg’s death, the Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer Company dropped Tarzan as too expensive. But the final audit showed that Tarzan Escapes had grossed more than $2,000,000, and the series was resumed.

The expensiveness of the Tarzan films lies partly in the nature of things and partly in the maniacal perfectionism of Hollywood. In the last picture, Tarzan Finds a Son, the producers wanted an effect of steam rising from a lake. They ransacked the country for steamy lakes and at last found the one they wanted in Florida. The lake refused to steam for them. They found that it would steam only on certain days and then only for about fifteen minutes in the morning. It took the location company seven days to get the pictures they wanted.

Most of the Tarzan scenes are taken out of doors. Bad weather causes losses running into hundreds of thousands of dollars in salaries of actors, technical men and mobs of extras. But the greatest expense is that of getting animals to perform. In making the last picture a lion cost the company tens of thousands of dollars by refusing to chase a small boy. The lion would either walk or lie down or lope off in the wrong direction. When he finally took after the boy, the boy forgot to run. The pay roll ran wild for ten days before the scene could be shot. Flamingos, zebras and other live items of African background, after hours had been consumed in maneuvering them into their places, walked off the set just before the cameras started.

It took weeks to teach the big elephant, Queenie, to limp when she was supposed to have been shot in the foot. In the meantime the baby elephant, Bea, was limping sympathetically, and it took weeks to break her of the habit. A herd of hippopotamuses broke out of their stockade in Sherwood Lake and ate up $25,000 worth of horticulture in the neighborhood. Fresh ostrich eggs, which were used by Tarzan’s mate in making omelets, cost twenty-five dollars each.

MGM spared no expense on the Tarzan yell. Miles of sound track of human, animal and instruments sounds were tested in collecting the ingredients of an unearthly howl. The cry of a mother camel robbed of her young was used until still more mournful sounds were found. A combination of five different sound tracks is used today for the Tarzan yell. These are:

- Sound track of Weissmuller yelling, amplified.

- Track of hyena howl, run backward and volume diminished.

- Soprano note sung by Lorraine Bridges, recorded on sound track at reduced speed; then re-recorded at varying speeds to give a “flutter” in sound.

- Growl of dog, recorded very faintly.

- Raspy note of violin G-string, recorded very faintly. In the experimental stage the five sound tracks were played over five different loud-speakers. From time to time the speed of each sound track was varied and the volume amplified or diminished.

When the orchestration of the yell was perfected, the five loudspeakers were played simultaneously and the blended sounds recorded on the master sound track. By constant practice Weissmuller is now able to let loose an almost perfect imitation of the sound track.

In some advance publicity on the latest picture, Tarzan Finds a Son, MGM let it become known that Tarzan’s mate, Jane Porter, was to die. Burroughs was in consternation. This was an awful tragedy to him. His second best literary property was to be callously abolished by a film company. He looked up his contract. It stipulated that MGM could not kill, cripple, or undermine the character of Tarzan, but it was silent as to his mate. Burroughs regarded Tarzan as a fundamental monogamist and would not look forward to building up a new romance around a widower. But shrieks from the fans all over the country changed MGM’s mind, and Jane’s life was spared. The movie company had nothing against Jane, but it was tired of losing the services of Maureen O’Sullivan, who played Jane, during the interminable months while bad weather and perverse animals were delaying Tarzan productions.

The movie company is sending an expedition to Africa for the next Tarzan picture. It is planned to make the okapi, least seen and known of large animals, a sort of co-star with Johnny

Weissmuller. The okapi is a relative of the giraffe and the extinct samotherium. It stands five feet high at the shoulders; its colors are purple and puce; its legs are striped like a zebra’s.

Dwelling in dense forests, rendered almost invisible by its coloring, the okapi — pronounced “okappi“ — is the cameraman’s toughest assignment. Burroughs has been asked to accompany the expedition for publicity purposes and is inclined to accept. He began to take a great interest in Africa after writing his first few books about it. He has a library on the subject today and has become a sort of authority on Africa. He would like to see some of the country about which he has written hundreds of thousands of words. Aside from brief excursions to Canada and Mexico and one trip to Hawaii, he has never been out of the United States.

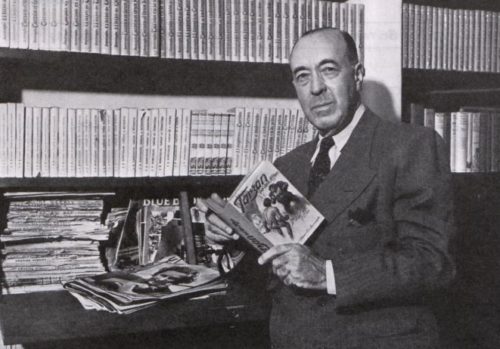

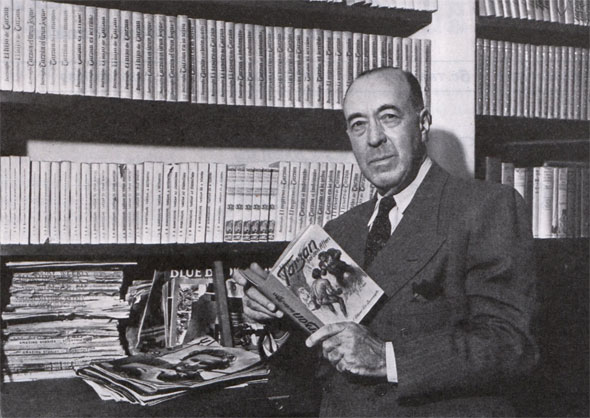

Burroughs is sixty-three years old. He is a little above medium height, and powerfully built. Horseback riding and tennis keep him fairly rugged, but he is always planning more strenuous measures to take off the extra ten pounds.

He leads a fairly busy life at his office at Tarzana, where he not only knocks off two novels a year but superintends the publication of his books and his other Tarzan enterprises.

The creator of Tarzan has a big poker face surmounted by close-cropped iron-gray bristles. He still looks a little military. Interviewers always complain that he does not look literary, but it is a convention of the interviewing craft to expect writers to resemble either Robert Louis Stevenson or Irvin S. Cobb.

Portrait of a Realist

There is probably less literary foppery about Burroughs than about any other living writer. He has enough fame for a thousand ordinary lions of the literary teas, but it has never meant anything to him except as it has boosted royalties. He has known few writers personally and does not like them as a class; he thinks they spend their leisure sitting around and trying pathetically to say smart things.

Burroughs travels with a non-Tarzan-reading set. If a personal friend ever tells Burroughs of looking into a Tarzan book, he mentions the matter with an apology or a hearty laugh. “My son,” says the friend, “left it lying open on a table and I happened to pick it up. Ha! Ha! Ha! I read a little of it. Ha! Ha! Ha!” If anybody compliments him to his face, Burroughs bristles, supposing that he is being heckled. But he is not mortified to learn that over in Japan little boys have been named Edgar after the author of Tarzan.

In his office at Tarzana, Burroughs has a soundproof study. At first that seems to be in the classic literary tradition. It recalls Carlyle’s everlasting campaign to fortify his study against the crowing of the demon fowls. Burroughs, however, soundproofed his study so that he can dictate his novels to a recording machine without disturbing his secretarial staff in the adjoining room.

The Unlikely Superhero of the Jungle

A century ago, the country’s hottest — and unlikeliest — action star was Elmo Lincoln in the role of Tarzan. Tarzan of the Apes premiered at New York’s Broadway Theatre 100 years ago on January 27, 1918.

To mimic the indeterminate African jungle of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ story, the film was shot in the swamps of Louisiana. Certain scenes were filmed in Brazil, such as the movie’s opening shots of lions, wild boars, snakes, and alligators. When it came to the apes responsible for raising the orphaned Tarzan, some extras were hired from the New Orleans Athletic Club to don monkey costumes and swing from the trees.

Turner Classic Movies’ Leonard Maltin called the film a “surprisingly watchable and straightforward telling of the Greystoke tale, though Lincoln looks like he’s about fifty years old, with a beer belly to boot.” Elmo Lincoln had a heftier physique than the 1930s and ’40s Tarzan played by Olympic swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, but he reprised his role in two more movies (The Romance of Tarzan and The Adventures of Tarzan). Lincoln was never again able to achieve film stardom, however, as he was thereafter relegated to small parts.

Edgar Rice Burroughs, the author of the wildly successful books, was an unlikely sensation himself. As our own Jeff Nilsson points out in “How Tarzan’s Author Did It All Wrong, and Got It Right,” Burroughs’ stories about the lord of the jungle broke countless literary and marketing rules, and they were filled with plot holes and leaps in logic. If Tarzan’s self-taught literacy is plausible, perhaps it follows that he could travel through time to fight medieval knights or Roman gladiators.

The 1939 profile of Burroughs in this magazine, “How to Become a Great Writer,” detailed Burroughs’ business failures that ultimately led him to sleepless evenings scrawling adventure stories in his apartment. The author’s imaginative writing seemed to benefit from its lack of accurate detail: “He had located his first novel on Mars because nobody knew the local color of that planet or the psychology of the Martians, and nobody could check up on him.” The same was true for Burroughs’ unspecified apes of the Tarzan series, although most have interpreted the anthropoids to be gorillas.

Burroughs seemed so ill-suited to his literary fortune that reporter Alva Johnston gave a revised list of tips for writers hoping to mimic the Tarzan-creator:

- Be a disappointed man.

- Achieve no success at anything you touch.

- Lead an unbearably drab and uninteresting life.

- Hate civilization.

- Learn no grammar.

- Read little.

- Write nothing.

- Have an ordinary mind and commonplace tastes, approximating those of the great reading public.

- Avoid subjects that you know about.

Even though he was no Oscar Wilde or Noel Coward, Burroughs created one of the most recognizable characters of the 20th century. Tarzan has appeared in movie theaters about 100 times, most recently in the form of Alexander Skarsgård in 2016. Given another century, the ape-raised warrior could grace the silver screen again and again, a far cry from his pulp fiction beginnings.

How Tarzan’s Author Did It All Wrong, and Got It Right

You’re working on the Great American Novel, and following all the best advice to new writers. You read widely from the great books. You study the rules of grammar and effective composition. You write about what you know. You write, revise, and write more. And you’re prepared to endure years of obscurity before your work gets popular.

Of course, you can completely ignore all these rules and still succeed. Edgar Rice Burroughs proved it. Without trying, he broke nearly every conventional rule for achieving literary success. He didn’t study composition or do much practice writing. He didn’t read widely. He didn’t even want to be an author.

Burroughs grew up with dreams of a military career, but when he applied to West Point, he failed the entrance exam. He enlisted in the army but was soon discharged for medical problems. For years, he drifted between jobs, selling cattle, managing an office, running a store, and mining for gold among other unsuccessful endeavors. He only started writing magazine fiction because he was desperate to earn a little money.

In 1911, he submitted an adventure story about life on Mars to All-Story, a pulp magazine. When it was accepted, he turned out two more in the same vein. And then he wrote Tarzan of the Apes.

Rather than writing about what he knew, Burroughs set his adventure-fantasy in Africa, a continent he only knew from a single book he’d read. Yet his ignorance of the country didn’t reduce the story’s appeal when it was published in 1912.

Burroughs soon followed up on his jungle hero with The Return of Tarzan. Before his death in 1950, he published 22 more titles in the Tarzan series. Between these books, he also wrote over 45 other novels, most of them set in outer space or the Wild West. They helped make Burroughs a wealthy man, but they were never as successful as the Tarzan series.

Burroughs began to exploit the public’s enthusiasm for his jungle hero despite the advice of experts. They warned him that he would over-market his character and the public would tire of Tarzan. But Burroughs ignored them and licensed his character for simultaneous use in comic strips, movies, and merchandise. Once again, he proved the experts wrong. Instead of diluting the appeal, mass-marketing Tarzan only made the character even more popular.

We’ve come a long way since Tarzan was the most popular hero of the day. Other characters have arisen to crowd him off the center stage of popular culture. This year, as he turns 113 years old, he probably wouldn’t seem impressive if you stood him in a lineup with today’s superheroes. But don’t let his lack of cape and skin-tight costume fool you. Modern superheroes, and their creators, owe their livelihood to Tarzan. He was a major turning point in popular fiction, and he made a new generation of do-gooders possible.

Before his time, the heroes in adventure novels were drawn from an established cast of chivalrous characters. They might be noble cowboys or soldiers, but just as often they were roguish characters who lived on the edge of society: outlaws, pirates, or detectives. But all heroes, if they existed on planet Earth, had to fight the usual villains with conventional weapons. Adventure stories had to stay within the fictional boundaries that readers knew.

Tarzan changed the rules for heroes just as Burroughs changed the rules for writing bestsellers. His jungle hero wasn’t limited to traditional strength. Raised by apes, Tarzan had developed incredible power. He could fight all manner of dangerous animals, including fantastic creatures and dinosaurs.

His African locale also opened new possibilities for villains. Tarzan fought slave traders (Tarzan Triumphant), mad scientists (Tarzan and the Lion Man), communist plunderers (Tarzan the Invincible), homicidal cult (Tarzan and the Leopard Men), and German soldiers in World War I (Tarzan the Untamed). And in a creative leap that better writers might have advised against, Burroughs dropped him into forgotten colonies of people lost in time, so he could fight medieval knights (Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle) and Roman gladiators (Tarzan and the Lost Empire).

As long as he was rewriting the rules, Burroughs could expand the realm of the possible. He made Tarzan implausibly smart. For example, Tarzan taught himself to read English from a book, even though no one had ever explained what a book was. In fact, he hadn’t even heard human speech when he learned to read. But then, there had never been a hero like Tarzan. And once readers got pulled into the book, they wouldn’t stumble over such impossibilities.

Burroughs’ great hero may have faded into the background of popular characters, but he is never forgotten. The character has appeared in about 100 motion pictures, not counting the several Tarzan television programs. No doubt there’ll be another Tarzan movie in the future. Perhaps it could be another Disney animated feature; the director of the wildly popular Frozen recently declared that Tarzan was the brother of his movie’s main characters.

Modern readers who pick up a Tarzan book for the first time might find Burroughs’ style a little dated. But he may also note the similarity between Burroughs’ hero and another orphan who grew up to wage a solitary, unbound-by-rules war on evil. The resemblance isn’t coincidence: Without Tarzan, there could be no Batman.