Scandal and Frustration: Teapot Dome and the Call to Reform

In 1924, Gifford Pinchot was fed up with Washington’s corruption and mismanagement of resources. Writing for the Post in May of that year, he alluded to a dirty deal of 1921 that was still being investigated: the illegal sale of public resources at the Teapot Dome, Wyoming.

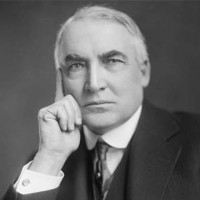

According to a recently written history, the theft was no slight bit of corruption. In fact, the orchestrators of the theft secured the nomination for President Harding knowing he would give a free hand to his supporter, New Mexico senator Albert B. Fall, who worked diligently to sell as many natural resources as he could grab.

“It was this policy of conservation which Albert B. Fall undertook to overthrow, and he wasted no time about it. Fall took office as Secretary of the Interior in March, 1921. By April first he had already launched the idea of transferring to his department the forests of Alaska, then under the wise and efficient care of the forest service in the Department of Agriculture. Along with this came the rumor of a transfer of naval oil reserves from the Navy Department to the Department of the Interior. The next month—May, 1921—that transfer was actually made.

“Soon afterward, Fall extended his scheme of transferring the Alaskan forests to his department to take in all the national forests, and was evidently making ready to include in his attack every natural resources that was under the control of his department already, or that could be brought under it.

“Mr. Fall was confident and ambitious, but he made one mistake. He took in too much territory. Moreover, he imagined that as a public official he still could live on the Three Rivers plane, and that the methods of the old frontier would go in Washington. He was seriously mistaken.”

Fall made private deals with Harry Sinclair of Mammoth Oil Company and Edward Doheny of the Pan American Petroleum Company. In return for gifts of cash and no-interest, don’t-hurry-to-pay-it-back loans, Fall allowed Mammoth and Pan American to take the oil from the reserves in Teapot Dome, Wyoming, which were intended to fuel the U.S. Navy in wartime.

The deal came to light. The public was outraged. Washington investigated. President Harding died before the inquiry reached him. No one was imprisoned for the crime except the fall guy; Albert B. Fall served one year in prison.

To the American public, the conclusion was as unsatisfying as that of the Enron scandal of 2001. Enron had grown from a pipeline company to a massive energy trader, but suddenly collapsed in a cloud of fraud, scandal, and suspicions of collusion with Washington insiders. Enron’s president, Ken Lay, died shortly before he was to be sentenced for his role in the collapse, which destroyed the jobs and pensions of 4000 workers.

Gifford Pinchot, in his 1924 Post article, was rightly scornful of corrupt business practices, but he unleashed his full wrath on Washington legislators who cooperated with such practices. His words, written 86 years ago, seem to capture a spirit very much alive today.

“Washington has been adrift. Some of the leaders of the people have gone astray. They thought the Ten Commandments had lost their force. It would be safe to wager that some of them think otherwise today, and safer still to believe that the American people see, as they seldom have seen before, the need for honesty in government; and are determined, as they seldom have been before, that honesty in government heneceforth shall prevail.

“It would be foolish to believe that the various investigating committees have found or will ever find all the dishonesty and betrayal that have been going on in Washington.

“What the country needs is a revival of faith in its Government. But there can be no such revival until the Government is worth believing in. There is no way the Government can be restored to public confidence unless the men who defiled it are thoroughly cleaned out.

“The breakdown of government machinery always stirs up the remedy brokers, whose confidence in any good-for-what-ails-you cure-all is the greater the less it has ever been tried. But the remedy does no lie in communism or Bolshevism or any other ism of the kind. It lies in a return to the simple, old-time, dependable virtues of personal and official honesty, fidelity and loyalty to the United States.

“Many years ago I was riding with a lumberman through the timbered mountains of Western North Caroline. He was no great talker, and neither of us had spoken for a long time, when suddenly he burst out: “Say, there’s a lot of good readin’ in the Bible, ain’t there?”

Yes; and a lot of it applies to the situation at Washington today. The trouble is perfectly diagnosed and the remedy accurately prescribed: “Thou shalt not steal.”