Love and Haight: The 50th Anniversary of the Summer of Love

How best to sum up an acid-inflected, flower-powered, whirligig of a long-ago summer in San Francisco? How to understand the lasting impact of that summer, which took root in a full-on Age of Aquarius neighborhood and blossomed into a counterculture that splattered across the planet?

Perhaps it’s fitting to begin by describing its final day.

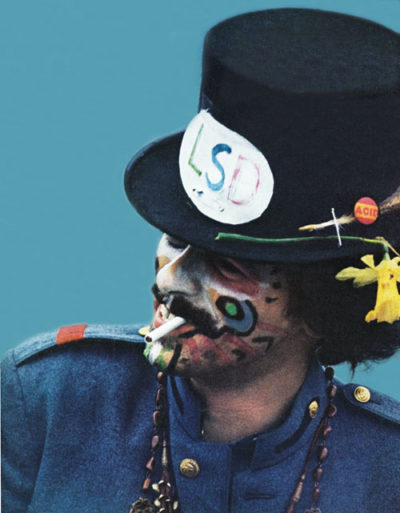

On October 6, 1967 — exactly one year after California lawmakers voted to ban the drug LSD — several hundred young bohemians gathered in the City by the Bay for what had been advertised as “The Death of the Hippie” funeral. Surviving film footage depicts a surprisingly carnival-like atmosphere. There was dancing in the streets. Someone played “Taps.” Sullen pallbearers carried aloft a large coffin that bore a single inscription: “Hippie, Son of Media.”

And that, ladies and gents, is how — officially and weirdly — the so-called Summer of Love concluded. Groovy.

The woman who organized the mock funeral, Mary Kasper, explained that following a season of merriment, music, confusion, and ultimately chaos in the streets of her city’s Haight-Ashbury district, “we wanted to signal that this was the end of it … don’t come here because it’s over and done with.”

Where once The Haight was iridescent with tie-dyed fabrics, colorful blooms, psychedelic storefronts, and a heady pharmaceutical culture, it had become, by October of ’67, a gritty tourist attraction. Worse, it had devolved into a magnet for thieves who’d descended from all around to prey on the vulnerable longhairs who had overstayed their welcome.

The Summer of Love, as initially conceived, was a brilliant marketing scheme. It was intended from the outset to be a convulsion of music, sex, and radical nonconformism. Come to The Haight to “turn on, tune in, drop out,” as Timothy Leary, the high priest of West Coast psychedelia, often exhorted his acolytes.

So, you might fairly ask, was the allure for young Californians the easy access to mind-altering drugs and sex?

Or the throbbing psychedelic music?

Or was it the gathering of the district’s anti-Vietnam War activists?

Yes.

Against the backdrop of a country in turmoil, here would be an aphrodisiacal admixture that some 100,000 people would find too tempting to pass up.

The whole thing sprang to life easily enough in the vibrant tapestry of The Haight, but by the time of the symbolic Hippie Funeral, the Summer’s mixed-up, mixed-media message had wafted across America and far beyond. The hippieverse had metastasized into a veritable, if not universally embraced, worldwide phenomenon.

From New York to London to parts of Asia, the hippie lifestyle was observed by onlookers with a combination of amusement and condemnation. It was a thing of kaleidoscopic beauty, to be sure, but some also thought it was a thing reeking of despair.

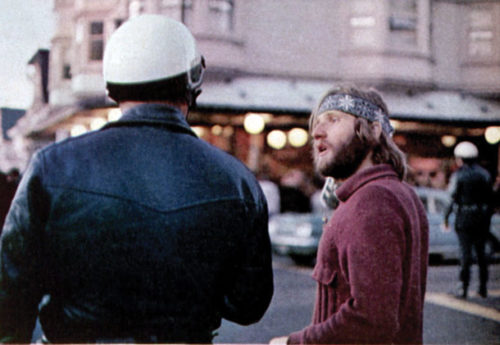

Ted Streshinsky, © SEPS

Today, 50 summers on, the questions remain: “What the hell was that all about? Was it, like, too far-out, bro?”

Those were the first questions I put to Dan Lewis, a Northwestern University social-policy professor and proud former hippie. Lewis will oversee the school’s Summer of Love Conference, taking place this July in San Francisco. “Over the years, I’ve been trying to make sense of that period,” Lewis told me when we talked. “There have been all these snarky, nasty, make-fun-of-kids-who-were-stoned people,” he said with an undisguised tone of contempt.

No matter what you may think of the Summer of Love, said Lewis, who runs Northwestern’s Center for Civic Engagement, what happened during that brief season has had a lingering influence on our way of life. For example, it led to the development of Silicon Valley.

Excuse me? You heard that right. According to Professor Lewis, some of the research (not his) that will be presented at the conference will trace “a lot of early thinking about information and communal groups and how that evolved into the Whole Earth Catalog, and then the internet, and then into cyberculture and eventually Silicon Valley.” The hippies are to blame for our smartphones! Well, sort of. And for the record, Lewis swears he no longer drops acid.

Actually, without too much of a stretch, you can make a pretty credible case for the argument: The deployment of social media on a global scale, pioneered by Facebook, was foreshadowed by what happened in 1967 at the intersection of Haight and Ashbury streets, where once stood the funky Unique Men’s Shop.

When I asked around among people who were there at the time — all of whom boasted that they still retain their hippie ideals, if not the iconic wardrobes — the underlying theme of that summer was not free love or LSD or rebellion against the distant war as expressed in the music. It was, fundamentally, a simple, sweet sense of community.

Ted Streshinsky, © SEPS

Among the astonishing catalogue of memorable songs that marked the summer of ’67 (“Good Vibrations,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “White Rabbit,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Light My Fire,” and “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” are but a sample), I was told over and over again that it was the Youngbloods’ “Get Together” that most perfectly captured the spirit of The Haight:

Come on people now,

Smile on your brother,

Everybody get together,

Try to love one another right now

Consider: It may have taken a while, but it was left to Mark Zuckerberg — not yet born in ’67 — to figure out how to connect latter-day hippies — and practically all other living persons — into a true worldwide community where everyone could in fact “get together.” Facebook, one might contend, is the natural evolutionary product of what the Youngbloods and their fans started.

In part because the hallucinogens raised consciousness (though not always mental acuity), hippies left us other gifts besides their remarkable music. The notion of recycling, for example. Scott Guberman, who plays in a Bay Area band with Phil Lesh of The Grateful Dead, told me that “the idea of recycling garbage came from the Summer of Love. The hippies were always concerned about sustainable living.” The whole organic movement, too, according to Guberman. But wait, there’s more. Credit the hippies for yogurt’s success in America because, Guberman told me, they “popularized” the treat.

It’s somewhat easier to link the lifestyle of the hippies to medical research now under way to use hallucinogens to help people quit smoking, break free of addictions, overcome depression, and more. For a long time, as a backlash to the recreational uses of these drugs, it was very difficult to get access to them for such research, but in recent years, that’s been changing. According to The New York Times, for example, such reputable institutions as New York University and Johns Hopkins University are studying the potential of psilocybin, the active ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms, to help terminal cancer patients face up to and accept their mortality.

If, in 1967, hippies “perceived these illegal drugs as a sacrament which was taken to achieve spiritual enlightenment,” as William Schnabel wrote in his book Summer of Love and Haight, they could never have imagined how legalized forms of these same substances would one day be sought by thousands of ailing patients. The apothecary that was The Haight helped give birth to these important scientific breakthroughs.

It also, unfortunately, led to serious issues with abuse of opioids. Sheila Weller, who has written extensively about the Summer of Love in Vanity Fair, said to me in a text message that “the mindset has endured a lot. … Taking drugs became hip, and the kids who could rebound and go back to their lives and their educations were the middle- and upper-class kids. The lower-class kids have spawned a second or third generation of opioid addicts.”

Lost in all of this is a small but telling irony. A free clinic that opened in The Haight in 1967 — it was designed to help heroin addicts — has recently been absorbed into a multimillion-dollar medical conglomerate named (wait for it) HealthRIGHT 360. Very corporate.

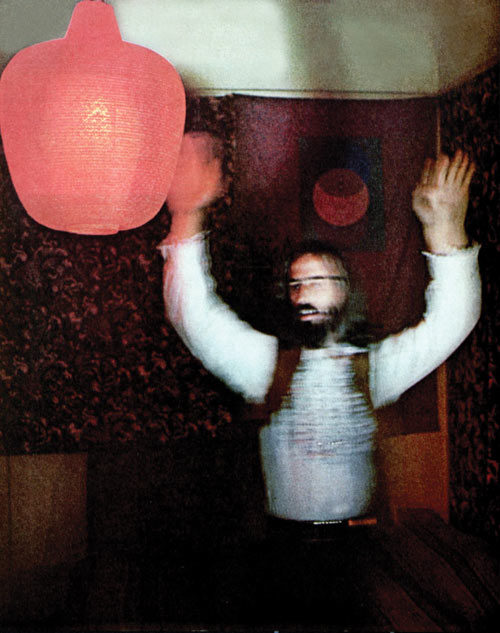

Jim Marshall Photography LLC

In many ways, the ’60s was a pivotal decade in American history — let’s just stipulate to that point and move on — but 1967 was the year of ultimate highs (pun intended). The celebrating and the innovating were likely connected, less by networking than by LSD and the Panama Gold grass, which could be easily had at the “happenings” and “Be-ins” in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge.

“All the creativity, the experimentation, the music — hell, ’67 was when we saw the rise of FM free-form radio and its influence,” Neal Mirsky, a longtime rock-radio program director, told me when we sat down to discuss the era. “It’s the first time we even looked at popular music as art. It was just such a transformational time in a lot of ways.”

The Haight, not surprisingly, was a sort of ground zero for all that. Writing not long ago about a concert that occurred one night in the neighborhood’s famed Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco Chronicle critic Joel Selvin observed, “Everybody who found their way there knew how wonderful the whole thing was and immediately embraced everybody else as fellow members of a special secret society.”

Vivian Murray, who was a high school kid hanging in The Haight during the summer of ’67, remembers that, for her crowd (and presumably Janis Joplin, who briefly lived in the same apartment building), the Summer of Love was driven not so much by utopian ideals but rather by an inchoate urgency to break away from The Man. In essence, to join that special secret society. “It was just our way of gaining freedom. The music scene had a huge effect. We’d escape into that.”

Alas, Murray, who went on to work a series of jobs, including in property management, doesn’t think the spirit of that summer will ever be resurrected. “We were into peace and love. Today’s kids are into video games: action, violence!”

In an effort to hold on to those memories, Murray maintains a Summer of Love shrine in her Washington State home — a room decorated with period furnishings and art. “And I still have my hippie beads,” she told me proudly. Old hippies die hard.

Ted Streshinsky, © SEPS

Witness Joe Tate, who was lead guitarist in Salvation, a psychedelic rock band that performed around San Francisco in the ’60s. Tate, who today continues to dress “like an unkempt hippie,” currently lives north of the city, in Sausalito. He boasted, “I still feel the same way about everything. I didn’t turn into a conservative. I see injustices every day.”

“Any chance of a hippie resurgence someday?” I asked. Unlike Vivian Murray, Tate is decidedly optimistic. “It could happen,” he said. Turns out he’s one among probably many thousands who’d welcome a hippie redux. When a British-based group organized for the purpose of celebrating the Summer of Love’s 50th anniversary — there are scores of such groups, thanks to the internet — it posted all its plans. On Facebook, of course. The final agenda item was an immodest throwback to 1967: “Save the world.”

Neato.

Cable Neuhaus writes about popular culture for the Post and other publications.

This article is featured in the July/August 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.