From Our Archives: Thomas Kinkade’s American Dream

One of the most collected American artists of the last half century passed away on April 6th. Thomas Kinkade, known as the “Painter of Light,” famously depicted idyllic scenes of churches and cottages in soothing, almost dream-like pastels. Inspired by his mother’s collection of Saturday Evening Post magazines, Kinkade told Post writer Ted Kreiter in 2003, “I think Norman Rockwell was my earliest hero.” In that same issue of the Post, Kinkade followed in the footsteps of his hero by painting the cover illustration.

In honor of this man who touched millions, the Post is reprinting Ted Kreiter’s 2003 article along with one of Kinkade’s two Saturday Evening Post covers.

THOMAS KINKADE’S AMERICAN DREAM

by Ted Kreiter

We’re on the phone with mega-artist Thomas Kinkade, whose tranquil scenes of village streets and buildings glowing with light have delighted millions of Americans. It’s 10:00 a.m., and the artist is in his studio, a 60-foot walk from his home outside San Jose, California. Kinkade goes there faithfully every morning before breakfast and often stays until dinnertime and sometimes after, six days a week.

“When I’m working on a painting, I get passionately obsessed with it,” the 44-year-old artist says. “Right now I’m working on a painting called The Bridge of Hope. It’s a follow-up to a painting I did called The Bridge of Faith.”

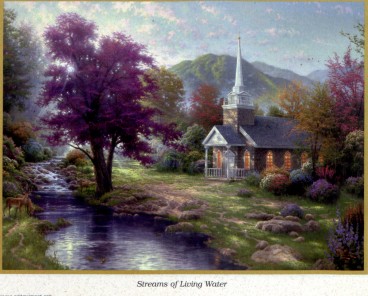

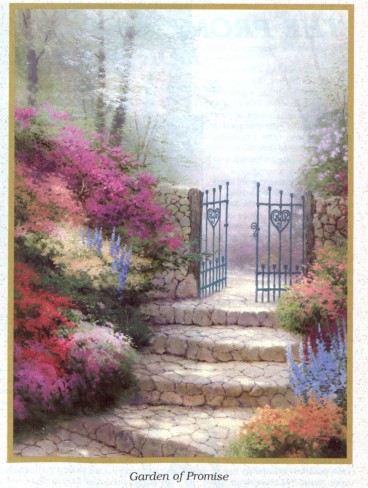

Bridges are a favorite subject of the artist, as are steps or grassy inclines leading upward or through a gate–images that are symbols of his religious faith. Some of his paintings actually are visual depictions of Bible verses, such as his A Light in the Storm, taken from John 8:12: “I am the light of the world.”

Many of his other works are not overtly religious, but whatever their subject matter, in any Kinkade painting, there is bound to be something more than first meets the eye. Those who look closely, for example, may be able to make out the initial N for Kinkade’s childhood sweetheart and wife, Nannette, which he works into all his paintings. His Golden Gate Bridge reportedly contains 156 Ns, which may be a record. What often goes unnoticed in Kinkade’s paintings, except by the very observant, is the artist’s playfulness, which he expresses by slipping in tiny details here and there. The initials on the tree in his Homestead House, for example, stand for Rhett Butler and Scarlett O’Hara. In his Paris, City of Lights, Kinkade is having a showing at the Louvre in Paris (something which in reality has not yet happened), but he has painted in a banner saying the exhibit is “sold out.”

Another humorous interloper into Kinkade paintings is America’s most beloved illustrator, Norman Rockwell. In one of the artist’s works, you can barely make out the famous illustrator’s big round glasses peering out from the windshield of an old car driving down Main Street toward the viewer. In another, Rockwell is seen at the corner of the painting hurrying up a walk toward a brightly glowing house.

“I think Norman Rockwell was my earliest hero,” Kinkade relates. “I was an artist since I was a baby. I remember my mom had a big collection of copies of [Saturday Evening Post] magazines, and that was really my introduction to those great illustrators. Not just Norman Rockwell, but Stephan Dohanos, John Falter, John Clymer, and others.” He recalls being amazed at his first sight of a collection of Rockwell paintings. “I just sat in rapture, mainly because I didn’t know how it was possible to paint things that realistic,” he says. “I hadn’t seen artwork that could capture a sense of visual reality in that compelling way.”

“I had seen so much art in the museums–still-life paintings and landscapes, and so forth–but that was very mannered compared to this,” he continues. “This was very compelling, very believable.”

As his interest in his own art grew, Kinkade says he was drawn to Rockwell for yet another reason: “his attitude of creating an art of meaning for people. I share something in common with Norman Rockwell and, for that matter, with Walt Disney,” he says. “in that I really like to make people happy.”

Another thing the two artists share is their compulsion when away from painting to get back to it as soon as possible. Rockwell was legendary for finding excuses to head out to his studio even on Christmas morning, Kinkade says. “That’s a challenge for me, too,” he adds, and admits that even while he is talking to us, he is working away on his painting. “When I have an interview such as our time today, I have headsets and I talk as I work,” he says. “I’m putting in some flowers right now as we speak.”

It soon becomes clear that while Kinkade has a passion for painting, his passion for talking is almost as great. He has a lot to say, about art–about everything–and if he were not so busy painting, traveling, lecturing, volunteering, and being a father to his four young daughters, he could probably be an outstanding full-time teacher as well. He’s also an avid reader with a collection of several thousand volumes in his library, but what he collects with the most gusto is art.

“Artists dream of growing up and making some money so that they can buy art,” he says. Fortunately, Kinkade’s artwork has made him financially very wealthy. “I don’t have yachts and airplanes and all that, but I have a bunch of paintings,” he says. “I have probably 200 paintings in my collection. My goal is to endow this collection to my hometown community someday so there could be beautiful art for people there.”

One painting that he is most proud of is his original oil of a 1934 Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Post cover. “It is a painting of a little boy clinging to a weather vane, and he’s looking out to sea,” Kinkade says. “It’s a beautiful painting. In fact, it’s one of the few paintings Rockwell mentioned in his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator. In chapter 10 or 11, I think it is, he starts out by saying that most of the stuff he painted in the 20s and 30s was pretty corny, like little boys hanging off a weather vane looking out to sea. When I read that, I said, ‘Hey, that’s my painting!'”

Kinkade is adamant that paintings should not be owned solely by museums or hang only in the homes of wealthy people. He believes firmly that everyone should have a beautiful painting. “You know,” he says, “it goes into a home; it is on the wall forever; it is part of the culture of the home. And in fact, it gets passed down generation after generation. It becomes part of the family heritage. It’s a powerful thing.” And Rockwell’s art, which at one time was looked down on simply as illustration, now belongs in that category of art that lasts.

“I mean, you go to that Norman Rockwell museum and walk around all those paintings up there in Stockbridge, and you know, this is a timeless part of our heritage,” Kinkade says. “Those images have meaning long beyond the painter’s lifetime. That’s what gets me excited about art.”

Kinkade travels the world to find the materials that end up in his own paintings. The cozy cottages he is so famous for really do exist. He lifts them from places such as England’s lovely Cotswolds and the Austrian Alps. Some have been the homes of famous people, such as the English cottage once owned by Beatrix Potter. In the U.S. he has borrowed The Pine Inn in Carmel, California; various buildings in New Orleans; and picturesque places on Fisherman’s Wharf for some of his paintings.

While he was painting in New England some time back, Kinkade came upon Norman Rockwell’s original studio. Not his last one in Massachusetts, but his earlier one in West Arlington, Vermont, the artist explains. “West Arlington is a little hamlet, really nothing more than a church and a covered bridge, and that’s about it,” Kinkade says. “But the Arlington studio is just full of memories. That is where he painted the Four Freedoms and, of course, most of his Post covers.” The Rockwell home is now a bed-and-breakfast inn. Kinkade knocked on the door and asked the lady who now owns the property in Vermont’s Green Mountains if he might paint in the old studio that had not been occupied since Rockwell left. She’d heard of Thomas Kinkade, of course, and she said yes.

Six months later, the artist returned to paint in the studio. For Kinkade, who never got to meet his idol Rockwell in person, it was a thrill. “It was just like I was living this little slice of this life that I had read about since I was a little boy,” he says. “It was an amazing time.”

One key to Thomas Kinkade’s art is that he grew up in the kind of small town made legendary in Rockwell paintings. His rise from poverty and obscurity is a latter-day illustration in full color of the American Dream. As Kinkade has said, “Art saved my life.”

“Placerville is the town I grew up in the Sierra foothills, not too far from Lake Tahoe in the High Sierras,” he says. “It was a simpler life when I grew up. The town was isolated. We lived on a little rural country lane that was unpaved.”

Thomas’ parents divorced when he was about five. “I was the only kid from a divorced home in that whole community that I knew of,” he says. “Everyone had a mom and dad, and I’d go to baseball practice and there’d be no dad there. It’s a very common thing now, but at that time it was a cause of embarrassment and shame.” He also was very poor. But he had something the other kids didn’t: his art.

“I was always the kid who could draw,” he says. “I had this talent, and it was the one thing that gave me some kind of dignity in the midst of my personal environment, because growing up, I was very impoverished.”

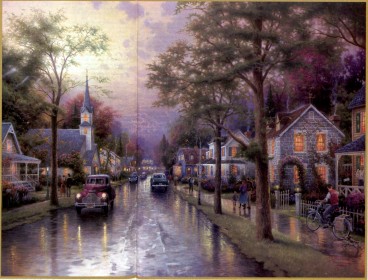

What Kinkade did not realize until long afterward was that the small-town atmosphere he grew up in would become the great calling card of his artistic future. “Saturday was the day the townspeople would show up on Main Street and do their shopping,” he recalls. “You’d bump into your neighbors, I’d get a haircut at Pete’s Barber Shop. I’d have a bag of popcorn from the Ben Franklin five and dime. The kids would hang out at the bell tower, hooting and whistling at each other and watching the other kids who were older cruise up and down in their hot rods and jalopies.” Some of those old cars have made their way into classic Kinkade paintings such as his Hometown Evening, which features a 1932 Ford Coupe among other vintage vehicles.

But Kinkade wasn’t always a fan of small towns or accessible art. As a young man, he longed to get away to the big city. At age 18 he headed to the University of California, Berkeley, on a scholarship. There he immersed himself in the diversity of ideas. “I thought my art would reflect my need to explore more sophisticated ideas, a philosophy that would be more of, you might say, an intellectual aspect of creative expression. But in fact, the reverse happened,” he says. “My college professor at the University of California pontificated one afternoon about the artist being an icon, an island, who had to be detached from the culture,” he recalls. “He would say, ‘Your art is all about you. It doesn’t matter if they understand it. It doesn’t matter if they have any interest in it. It’s all about you.’ That just grated on my sensibilities.”

Later, while studying at art school in Pasadena, Kinkade finally rejected the “pseudo-sophistication” he had learned at college and decided that the modernist art he had become enamored with was not really for him. He wanted his art to appeal to everybody, not just art critics.

Now his paintings reflect what he believes are the “foundational values.” “I try to create images of inspiration, hope, a simpler way of life,” he says. “Messages that linger in the mind and remind you that the world is not all the ugliness you see on the 10:00 news–that there is good news and good stories about good people that are more compelling than that bad news you see on CNN.”

Today, as Kinkade puts it, “some 10 million people wake up every day to one of my paintings.” Not only does it put them in a better frame of mind, it enables the artist to reach a huge audience of Kinkade fans for the sake of his many charities.