Torpedo

On the morning of her 13th birthday, Yésica eats her Os in front of the television, where she also sleeps. If there is no soy milk, she uses orange juice, and if there is no orange juice, she uses water. The morning news is a house fire, a school board vote split five to four, killed soldiers from Fort Bragg, lead in the water, a cat that can count to 12, a recipe for persimmons, the forgotten fruit, a pill that helps people who fart a lot, the weather, and sports.

Five to four makes Yésica feel itchy. With it, she makes nine, then divides by three, which makes her feel smooth. Farters eat too much gluten, as is commonly known. “I am allergic to gluten,” Yésica tells the screen.

Her Os are made of brown rice and that is something viewers might be interested in knowing. The weather will be mild, with a 60 percent chance of rain in the viewing area this afternoon, the weatherman tells her.

The weatherman reminds her of Mrs. Pfeffelman, her Science teacher. Except the weatherman uses Maps, not Books. His black hair is flat and shiny as her mother’s painted fingernails. When Mrs. Pfeffelman talks about numbers or the winds or the way heat rises from the ground to make a thunderstorm, she makes the things she is talking about seem small, like a ball or a box of jacks. On her desk, Mrs. Pfeffelman has metal clothes hanger arms holding the planets and a yellow Styrofoam sun. When her finger pushes the Earth, around it goes until the arm squeaks to a stop.

Books have things Yésica can see, not truth. Books with a big B, like Benson, places people go just as easy as getting in a car. But truth has a small t, everywhere and nowhere, smeared on her skin like her mother’s lotion. A capital T in truth would be spiky and too green. The small t is sleek, a handle that fits like her hand on a hairbrush. Perhaps there will be rain, but it won’t fall exactly when or exactly where the weatherman says on his Map.

Yésica likes sports, but she can never wait for it. She has to leave for school at 7:55 a.m., the color of daffodils. Otherwise, everything turns grey and prickly.

After rinsing her bowl and spoon, Yésica picks clothes from her clean pile. She has five white Henleys and five pairs of black Bermuda shorts, with black cotton crew socks rolled in balls and her Converses, black, with black laces that she ties in a double bunny, tight as she can. Before she will wear clothes, her mother washes out the sizing, 10 cycles minimum. Otherwise, the fabric pokes her like puppy teeth.

If there are no clean socks or the power goes out or if the Os box is empty, Yésica screams. This is the way of things. The screams wake her mother, who comes in to brush Yésica’s arms and shoulders with a nail brush. When Yésica stops, her mother uses the lotion. Then the day can start fresh no matter what number is on the clock.

Outside, the sun is hot. Her bicycle has long handlebars and a skinny, black banana seat. Yésica’s mother bought the bike for 55 cents. 5 + 5 is 10, a blue number. The rubber handles have silver streamers, which Yésica trimmed into nubs. She calls the bike Torpedo, because that is what is written on the frame: “TORPEDO.”

Every school day, she pedals to the end of Megan Faye Lane, then makes a right onto Blossom Falls. Megan Faye is a dead girl. Mr. Hobson Goode found her in the woods where he planned to lay cement pads for new trailers. The name is his way of honoring her, he told Yésica’s mother once, and to make sure the sick son of a bitch who did it goes to the death chamber, where he will be pumped full of rat poison. Megan Faye died when she was four, which is 1 + 3.

Today, Yésica’s mother will bring confetti cupcakes and cranberry juice for a birthday party in class. But Yésica never gets to class. As she pumps the pedals, she sees something on the side of the road that wasn’t there yesterday: a shoe. The shoe is muddy and kid-sized. Over it, the bushes are green and dense, cut straight as walls with Mr. Hobson Goode’s brush hog. Her mother tells her, “Go straight to school on that bike or you won’t have it any more. En serio.” But her mother never talked about seeing a shoe.

Yésica lays Torpedo on the roadside gravel. Carrying her backpack, she sees a dim path that leads into a brush tunnel. Further in is another shoe: the right foot. Kid-sized prints lead away from the shoe. The mud is so wet that she can count toes: 5. 4 + 1 = 5. 5 + 5 equals 10. Clear as the blue sky, she hears an invitation.

She knows this path. It is the path to where Megan Faye died.

A squirrel chucks at her: chuck, chuck, chuck. She wants to throw a stone, but there is only mud and rotting leaves. The path leads in, then turns to the right. She finds a Jolly Rancher wrapper that is pink and twisted. Pink makes her sneeze. Against her thigh, Yésica flattens the wrapper, then folds it into a triangle so that only the white inner side shows. Three points, worth keeping. She puts the wrapper in her pocket.

Sometimes, boys fight in the woods. They build forts and smoke. Yésica doesn’t hear any boys, only her own breath and squirrels and the trail with its signs, whispering like a television turned down very, very low.

Yésica reaches the pond Mr. Hobson Goode dug out to get the dirt he uses to flatten lots before he puts in cement pads. The edges of the pond are red clay. Pine trees, their roots sliced through and matted, angle over the brown water. Once, a boy whose name she does not know fell in. He had to be rescued with a ladder. Yésica saw him climb out with his clothes coated in thick, green scum. Water rolled down his brown legs and she thought of ducks on TV, when they tip their butts in the air then come up again, shaking the water off. His shorts hung heavy with water and low, and she wanted to run her finger down his bared stomach, following the curve that started at the sharp points of his hips.

She didn’t. Yésica doesn’t like people touching her without asking. Even then, it hurts. Sometimes, she wraps her mother’s arms around her waist, just for a second, then flings them away again. If Mrs. Pfeffelman touches her, she bites.

Yésica hears spoons clatter in a metal bowl. A red bird with a pointed head perches on a branch. Looking straight at her, the bird squawks: 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 times. Seven. Seven tastes like hamburger-flavored tofu, moist and meaty. Her cousin Brittany is allergic to soy and breaks out in welts if she eats it. Seven makes Yésica hungry, but since she isn’t in the school cafeteria, she can’t eat her lunch.

She keeps walking.

By now, she can feel Mrs. Pfeffelman wondering where she is. Science is first period. Soon, Mrs. Pfeffelman will call her mother. Her mother will say to Mrs. Pfeffelman, “What on earth are you doing waking me up from mi descanso?” and Mrs. Pfeffelman will say, “Yésica is not here. Where is Yésica, is she ill?” And her mother will call the police.

This happened before. But before, Yésica did not see a shoe or a Jolly Rancher wrapper or a bird speaking to her in 1s. She had never had a thirteenth birthday before. 1 + 3, she thinks, equals 4. 4 is mysterious, a house with no door. On the other side of the pond are more woods and more brush and the place Mr. Hobson Goode said he would never ever go again.

Yésica is going. The red bird flits over her head

Yésica sees a gleam of metal, then a grey curl of window screen. Propped against a tree is a doll, its arm pointing toward a small trailer. Again, spoons clatter. Spoon is an especially nice word. Spoon is the thing it means. Round and hard and cold. The n is the handle end, which she likes to press into the soft pad on her thumb. Yésica eats with the same spoon every day. Her tongue knows it as well as the insides of her own mouth. Her mother says she has her grandfather’s mouth, with a broad lower lip and a deep bow. Pucker-mouth, her mother says. Pucker up, when she wants a kiss. Pucker makes Yésica laugh. Yésica kisses the air, and with her hand her mother catches the kiss, slow as a moth, and swallows it whole.

The doll warns her: be careful. The doll’s eyes hurt her to look at, so Yésica follows where the arm points, at a stump with an axe sunk in it and wood chips sprayed over the wet ground. Next to the stump is a bucket with a hole. She counts 8 crushed cigarette butts. She hates the number 8, with its rotting, twisted smell. The year she was eight, she did not say a word, for fear the stink would crawl right up her words, down her throat and into her soul, which is absorbent as paper towel.

The day before her 9th birthday, Yésica wrote a note to her mother: “What time was I born?”

Her mother stroked Yésica’s plush snake, since she knew better than to touch Yésica without an invitation. “9:33,” she said.

“AM or PM?” Yésica wrote.

“AM. They swaddled you during the morning traffic report. Like a red sausage. Screaming you were as they took you away. Maybe that is why you can’t get enough noticias.” Her mother wore her Hardee’s shirt, deep blue, and her red nametag: Moni. The snake was named Moni, too. Yésica loved the color blue so much that she had to close her eyes and dig the spoon into her hand.

“Ha,” Yésica wrote. The next day, Yésica spoke at exactly 9:33 a.m.: a rounded, pleasing number, like the hood of a car.

Now she hears voices: a man and a muffled voice that could be a man or a woman. Neither voice fits a kid-sized shoe. The trailer is not like the one she lives in with her mother. Theirs is long and white, with a wood porch in front that Uncle Toño built and metal awnings painted bright blue. Her plastic blue pool is in front, too, with two white plastic chairs. The mailbox has nine plastic daisies at its base, yellow and white and blue, 3 + 3 + 3. This trailer is splotched with grey and sags, the hitch propped on cinder blocks. The rubber tires are sunk in mud. Yésica can see the tracks from where the trailer was dragged in. A black pipe pokes from one window. The screen door hangs off the frame. To one side is a metal barrel next to a pile of something smoldering. Old clothes and empty cans are scattered everywhere.

The voices come and go. The trailer creaks when the people talking move inside. Then Megan Faye is at her side.

“I knew you would come,” Megan Faye says. Her voice is thick, like Yésica’s mother’s when she wakes up.

“It stinks,” says Yésica.

“Stinks,” repeats Megan Faye.

Megan Faye wears a nightgown with a lace collar. The fabric is worn flannel, pink, so Yésica sneezes. Her ghost face looks as if someone has dragged an eraser over a pencil drawing. Megan Faye doesn’t smell like anything. The trailer smells like sick.

“What am I supposed to do?”

“Eat nothing,” the ghost answers, “or you will never be able to go home.”

“I ate my Os.” Yésica remembers her backpack, heavy on her shoulder. “My lunch is in my backpack. Can I eat my lunch?”

“No,” counsels Megan Faye. “They cannot see me, but they can see you. There is a boy here who needs your help. His name is Brad Connor.”

Megan Faye vanishes.

Yésica doesn’t know any Brad Connor. Does Megan Faye want her to knock on the screen door and ask for Brad Connor? Why should she do anything for Brad Connor? She doesn’t want to touch the lopsided door, since it makes her skin feel like a rash. Yésica wishes that her mother were there. Yésica thinks carefully about what her mother might say. Here are things her mother says: keep the television sound low so I can sleep por diós. Go straight to school and come straight back again. Money doesn’t grow on trees. Be polite. Remember to say please and thank you. It’s like the 3 that comes after the 2, her mother says, or the square root of 16. It is one thing that follows another thing, something tú tienes que hacer.

√16. How beautiful, a number in its own tidy trailer, with a hitch. She has to say thank you, Mrs. Pfeffelman, or please, Mrs. Pfeffelman, may I use the bathroom. Then she has to wait, wait, wait! for the person to say yes. Mother says that people talk to people and wait for them to talk back. At work, her mother says please and thank you until she is blue in the face, she tells Yésica. This is what people expect. This is how people get along.

“Blue in the face,” Yésica repeated.

“Not really,” her mother answered. “An expression. Like green with jealousy or red with rage.”

Other times, her mother says things like Don’t talk to that man! or Get away! Once, a man stopped in front of the trailer while Yésica was in the pool. He rubbed his pants over his wiener. Yésica wondered if this was some sort of exercise. Then her mother, who had been hanging laundry, grabbed her arm and pulled her into the trailer. Yésica screamed, but her mother didn’t let go. Her mother got a blanket and Moni, the plush snake, and wrapped the two of them tight as presents. Eventually, Yésica stopped and her mother got the lotion.

As she is wondering about Brad Connor and what her mother would say, a man leaves the trailer. His hair is long and grey. He wears a black t-shirt under a flannel shirt. She sees the ridge of his jaw bone and how his collar bone juts out and how the bones of his knuckles are swollen and creased in dirt. He lights a cigarette. Then he takes a long drink from a can of beer. Yésica smells the beer along with sweat and something else, like the chemicals under the kitchen sink at home. The man squints at the sky, then looks straight at her, crouched in the bushes. But he doesn’t see her.

He is 11, sharp as sticks: Stick Man. But Yésica thinks, no, that can’t be, there is no 9 or 10. There’s no order, and tú tienes que hacer. Then she remembers: Megan Faye has 9 letters in her name. Brad Connor has 10. Stick Man is 11. Twelve is tricky, since it separates the single digits and what she thinks of as true teens, where numbers get tastier, but also more dangerous. Of course, she is 13. Then she thinks: truth and its handle. Thirteen. The letter t. Torpedo. The truth is inside the numbers and the words like cream in a cream-filled doughnut. Something is about to happen and she is at the center of it, waiting.

A chain clanks. From behind the trailer comes a creature. Yellow eyes dig straight into her and she shudders. A low growl seeps from its mouth. The black and brown fur over its ribs form the number 12.

The hairs on Yésica’s neck rise and she stops breathing.

“Shut up, Brutus,” Stick Man says.

“You must find a way to distract it,” whispers Megan Faye. The ghost stands next to her, cradling the doll.

“How?”

Megan Faye is gone again. This must be the way with ghosts, Yésica thinks. Just as people need her to look them in the eye and say words back, even if the words are stupid and obvious, like “Good morning” on a sunny morning or “Have a nice day!” when there is no way to change the kind of day a person will have, ghosts come and go as they please. Tricky as 12s. Her mother would tell her to be polite. So she must find Brad Connor and at least say hello.

“Get in here,” a voice from inside the trailer shouts.

Stick Man drops the can and crushes it beneath his boot. He goes back inside the trailer.

Brutus growls again. Yésica starts breathing and Brutus’s eyes narrow, needles on her skin. Stick Man and the other person are shouting. Yésica’s stomach rumbles. She has it: lunch. Yésica pulls her lunch bag from her backpack. The lunch bag has Velcro tabs, padding to keep food cool and a compartment for her sandwich, spelt bread with barbecue tofu and shredded carrots. There is an Ambrosia apple, chocolate-covered cranberries and a box of chocolate soy milk. Yésica pulls off a piece of tofu and throws it at Brutus. The dog’s jaws snap in the air. She throws another and another. Brutus does not look at her anymore, only at the flying tofu. So Yésica throws the whole lunch bag as hard as she can. Brutus catches it and drags it beneath the trailer.

For the first time, Yésica notices a pile of rocks under some low bushes near where Brutus had been growling. A stone is wedged over a gap. When she rolls the stone away, she sees steps cut out of the red clay. In the blackness is a bare foot, pale as a mushroom.

“Brad Connor,” she says.

The foot twitches.

“Hello, Brad Connor. Good morning, Brad Connor. How are you today?”

Yésica picks up a twig to touch the sole of the foot. It twitches again. “My name is Yésica Fernández. Today is my birthday. I am 13. I have come to get you.”

The foot disappears. In its place is a face. A boy’s face, streaked in green and brown and some wet red. “I can’t,” the face says. “I’m tied.” The boy crawls out. She sees that a rope is wound around an ankle. The rope is tied to the same stake as Brutus.

Yésica is excellent at knots, patient and strong-fingered. She is careful not to touch his skin as she works off the rope. Still, the boy does not get up.

“Brad Connor?” she says, looking off his shoulder so as not to get trapped in his swirling eyes. He holds out his hand. Her skin crawls but she can’t look away. His eyes are blue. “Help me up. I can’t stand alone. I’ve been in there three days. I’ve pissed myself,” he finishes, licking his filthy lips.

He stinks. He cannot stand without her. She puts her left thumb pad in her mouth and bites. As she does, she reaches out with her right hand. He grasps it and she pulls. His fingers are like worms and as shivery. Brad Connor has no clothes. She bites her hand harder, until she tastes her own flesh. Then he is beside her, still hunched but standing, his arm on her shoulder.

Megan Faye claps. “Hooray!”

“Who in Hell are you?” Stick Man is standing at the trailer door, his mouth hanging open. Instead of teeth, he has glistening nubs. “Marsha, get the fuck out here.”

From the trailer, a thing emerges. It has the body of a woman, but the face is a machine, with a black box where the mouth should be and goggles for eyes. Red patches crawl up her arms and down her bony legs. “What the fuck,” Yésica hears, as if from far away.

“What the fuck,” repeats Stick Man. “Boy, you get back in there.”

“No,” says Brad Connor. Yésica is whimpering with the weight of his arm, and her tongue tastes her own blood. She sees his wiener and the curve of his belly. He is not the boy from the pond. She has never seen Brad Connor before. She knows her mother would want her to hold Brad Connor up, no matter how much it hurts. No one has ever written that in a Book.

“Let’s go,” Brad Connor says to her.

“You’re not going nowheres.” Stick Man grinds his cigarette into the mud. “You are going to take your punishment.”

“Cocksucker,” says Brad Connor. “You are not my Dad.”

Stick Man steps up to wallop the boy with his fist. Brad Connor ducks, and his arm whips from Yésica’s shoulder. Yésica can finally take her hand out of her mouth just as Megan Faye spreads her tiny, razor-sharp wings. The ghost lifts up and thrusts a tree branch at Stick Man, who jumps back. Brad Connor runs.

“This bitch.” Yésica sees the woman’s face now and knows that she should say something. But the woman doesn’t wait for her. “I’ve a mind to … ”

Now truth is too big and tricky as a tornado. Yésica doesn’t know what comes next or what her mother would say or even where she should put her hands, so she whirls them. She wants to count washing machine quarters and stack them in piles or roll in the fall grass when it is toasted and sweet, like Crackerjack, or draw the blanket tight around her shoulders and listen to the weatherman talk about the high-pressure system just off the coast. There are some truths that have no words or numbers at all. Here is one: boys are not to be buried in the ground.

“Hello, Brad Connor!” she yells. The squirrels chuck madly, as if agreeing with her, and the red birds squawk in perfect 7s, surrounding her with invisible thorns.

The woman runs at Yésica, and Megan Faye’s eyes grow circular and vicious. Without warning, the ghost slices her wings at the woman’s scrawny neck. At first, the woman ignores her, as if the wings are just flies or Yésica’s own screams. Her hand closes around Yésica’s arms and Yésica screams even louder. Just as the woman starts to shake her, Yésica hears the woman gasp. The woman’s hands fly to her own neck and claws. She gurgles. Megan Faye batters her from behind, and Yésica learns another truth: there is no escaping a ghost’s fury. Yésica sees no blood, only the effects of a slow spread of nothingness in the woman’s lungs. Yésica takes her two hands and pushes the woman away.

“Lord have mercy,” the woman gasps. She bends, then topples over.

The squirrels chuck-chuck-chuck as Megan Faye swallows every bit of air around the woman. Brad Connor lifts a pair of filthy shorts from the ground and pulls them on.

“Water!” Stick Man cries. He kneels beside the woman. “Marsha, what the fuck? Where’s your inhaler? Girl, get you water for her!”

Yésica always does as she is told. She enters the trailer and sees a sink and a cupboard. The woman had been cooking something, but it is not food. The stink makes her eyes water. Beside the sink is a chipped and cracked glass. She can’t bear to touch it. Instead, she grabs a paper cup with “Hardees,” like the ones on her mother’s name tag. Yésica fills the cup and brings it to Stick Man.

“Here,“ Yésica says to him. “Here,” she repeats. Still he doesn’t respond. “Tú tienes que hacer,” she says. But she might as well be a ghost. He pays her no attention. She sets the water down, and it tips over. He doesn’t seem to care.

Brad Connor is gone.

Megan Faye is back to her original size. She sits on the stump where the chain holding Brutus is attached to a metal ring. Brutus is still under the trailer, ripping Yésica’s lunch bag to shreds. Megan Faye sucks her thumb.

“Why did you hurt her?” Yésica asks.

Megan Faye doesn’t answer.

Stick Man weeps. The woman curls on the ground as if asleep. “She never hurt no one,” Stick Man is saying. “That boy is bad to the bone. Stole. Hit her. Little cocksucker. Now she’s dead and all because of him.”

“Brad Connor was tied up in the ground,” Yésica is saying, more to herself than to him. “He was dirty. He had no clothes. He pissed himself.”

From the place where she left Torpedo, Yésica hears her name. Hobson Goode is the first to enter the camp. After him come three policemen. They talk into the black radios they wear on their shoulders. One of the policemen comes up to Stick Man, who is slumped beside the woman’s body. Megan Faye is gone. The doll sits against the tree, its arm is in its lap.

Then her mother appears, still in her PJs and barefoot. Yésica tells her mother about Brad Connor. She shows her the cave. He had no clothes, she says, and his legs were shiny with pee. She doesn’t tell her mother that she saw his wiener because her mother has gone white as Brad Connor’s mushroom foot. She wishes her mother would explain, but then she remembers that she threw her lunch bag to the dog and the dog has eaten it. Maybe her mother is angry about the lunch bag. Yésica is always losing them and if it’s not one thing it’s another, her mother says, and she should be more careful and money doesn’t grow on trees goddammit.

Yésica says she is sorry about the lunch bag. She will buy a new one with her allowance. Her mother shakes her head, shakes and shakes. Then her mother says, well, let’s go home, you are probably hungry. And she is.

Yésica walks behind her mother, placing her feet inside her mother’s footprints. Torpedo is just where she left it. She rides it home, then sits at the kitchen table to wait for her mother to arrive. Her mother makes her soup and gives her a confetti cupcake. Yésica hears her mother call in sick.

Truth is exhausting. Yésica has had enough for one day. Yésica rinses her bowl and spoon, then curls up in front of the television and falls asleep in her usual spot. A tap tap tap on the roof announces rain.

Brad Connor is on the news that night, boy rescued by local girl. “What a story!” the weatherman says before he talks about the high-pressure front approaching the viewing area. They show a picture of the boy, clean-faced and smiling. Yésica wouldn’t know him except for his eyes, which still hurt to look at.

The next day, while Yésica is at school, Hobson Goode hauls the grey trailer away. Although her mother forbids her to go to the pond, Yésica starts to sneak away when her mother is at work. She is careful to hide Torpedo in the bushes, so no one will bother her and her mother will not take the bicycle away.

They continue to meet. Megan Faye rarely speaks. She doesn’t have to. She and Yésica understand what happens in the woods. One thing follows another and tú tienes que hacer. The squirrels chuck and the birds speak in sevens as they hop from branch to branch. Even when it rains, the animals take the bits of bread and tofu Yésica throws, always hungry for more.

Featured image: Shutterstock, vesnam, ArtBitz, Richman21

“Mr. Tutt Fights a Draw” by Arthur Train

American lawyer and writer, Arthur Train, was a prolific author of legal thrillers. His most popular work featured recurring fictional lawyer Mr. Ephraim Tutt. In “Mr. Tutt Fights a Draw” Mr. Tutt is disturbed when he learns about the burning of land nearby, and he immediately takes legal action against the arsonist.

Published August 8, 1936

The Santapedia, which flows into the Bay of Chaleur at Ste. Marie des Isles, is one of the most celebrated salmon streams in Canada. On it is located the Wanic Club, which owns, perhaps, the best fishing water in the world and is composed of six eminent men — Sewell T. Warburton, president of the Utopia Trust Company of New York; Sidney Arbuthnot, president of British Columbian Railways; George R. Norton, president of the British Colonial Trust Company; Chester L. Ives, president of the Royal British Bank of Canada; the Right Reverend Lionel Charteris, Bishop of St. Albans; and last, but not least, Mr. Ephraim Tutt, honorary member. How the latter achieved his place in this Olympian body of sportsmen may be read in a piscatorial chronicle entitled Mr. Tutt’s Revenge. But a lot of water has flowed over the rapids of “Push-and-be-damned” and through the Oxbow since that happened.

Mr. Tutt had had the happiest three weeks of his life in outdoor companionship with the most congenial men he knew. Regretfully, surrounded by his old friends, he left the clubhouse veranda and walked down to the little beach, where his seventy-nine-year old guide, Donald McKay, was waiting in the canoe to paddle him back to civilization. Clad in khaki breeches and high-laced boots, he, nevertheless, wore his ancient stovepipe hat tilted on the back of his head — the only way to carry it, as he explained. “Well, Eph,” said Bishop Charteris, taking both the gnarled old hands in his, “goodbye until next year, and God bless you.”

“Thanks, My Lord,” smiled the old lawyer. “Sorry I can’t bestow my episcopal benediction in return, but you’re a swell guy and I wish you luck.” “Goodbye! Goodbye, old man!”

“Here’s your lunch, Mr. Tutt,” interrupted Charles, the decrepit Negro functionary who had served as the Wanic’s butler, valet, cook, waiter, barkeep and private orchestra for the past thirty-five years. “I done slip in a bottle of the Bishop’s Madeira,” he added in a whisper.

“You old thief!” Mr. Tutt slapped him on the back… “Well, boys, so long! Leave a few fish!”

“If anyone hooks Leviathan again, send me a wire!” He stepped into the canoe, settled himself comfortably against a gunny sack and lighted a stogy.

“Do you expect to make Ste. Marie des Isles tonight?” asked Charteris. “Easily! Donald and I will ‘boil,’ as he calls it, at Portage Brook, reach the Nipsi by four o’clock and be at The George in Ste. Marie in time for supper. I’ll get a good night’s sleep and catch the Whooper when it comes through at five tomorrow morning.”

“I’ve got a better idea than that,” said the president of the British Colonial Trust Company. “You know where the Canadian Seaboard and Gaspe crosses the river below the Stillwater Pool, twenty miles above Ste. Marie? Old man Micklejohn, of Montreal, has a camp there. He’s leased most of the land on that part of the river — enough to give him a practical monopoly of the fishing rights, although I believe there’s a farmer owns a short strip on the other side. I’ll call up Micklejohn and tell him you’re coming, and you can spend the night with him. That will give you time to fish the Stillwater before dark.”

“But I’d have to get up by three o’clock tomorrow morning and paddle the twenty miles downriver to Ste. Marie or miss my train,” protested Mr. Tutt. “You forget I’m getting old.”

“No, you wouldn’t,” retorted Norton. “That’s the point. Micklejohn’s camp is just above the railroad and, under the law, the train has to stop there for three minutes because it’s a drawbridge.”

“You’re wrong about that,” said Sidney Arbuthnot, president of British Columbian Railways. “The train doesn’t have to stop unless the draw is open, which it hasn’t been in fifteen years. The reason it stops is that Micklejohn, who is president of the company, orders it to. He gets all his mail, ice, milk and eggs, everything he needs, that way fresh every morning, just as conveniently as if he was at home.”

“What a cinch you railroad men have!” laughed Sewell Warburton, shaking his head. “Imagine what would happen if the president of the New York, New Haven and Hartford ordered the Yankee Clipper stopped at his country place to deliver his groceries!” “Yes, but there’s some difference between the Whooper and the Yankee Clipper,” commented Chester Ives.

“A difference of about fifty-five miles an hour,” nodded the Bishop.” Well, anyhow,” continued Norton, “the point is that, whatever the reason, the Whooper stops at the bridge and that, by taking it there, you can save the trip by river to Ste. Marie, besides having a chance to fish the best pool in the province besides.”

“Sounds good to me,” declared Mr. Tutt. “I’ve always wanted to throw a fly over the Stillwater.” “I’ll call up Micklejohn at once,” said Norton, “and tell him to be sure to have the train stop for you. I know he’s there.” “Sure, he’s there!” grunted Donald McKay, and spat over the side of the canoe. “But will he want me to spend the night with him? Suppose he should be full,” said Mr. Tutt. “There’ll be plenty of room,” Norton assured him. “Micklejohn never has any guests.” “Well, goodbye!” Mr. Tutt waved. “Goodbye and tight lines to all! …Let her go, Donald!”

They pushed out into the stream. Against the high bank below the clubhouse stood his five friends waving their farewells. A lump came into his throat. God bless ‘em They were the best — the top! Fishermen always were!

For the first hour, with his long legs stretched comfortably before him, Mr. Tutt cast lazily with his trout rod, first right, then left, while Donald McKay paddled him swiftly down the Santapedia; then, as the sun grew hotter, he unjointed the rod, put it with the others in his leather case and abandoned himself to admiring the passing scenery and to ruminating upon the river’s history. To the north, as far as the St. Lawrence, stretched an unbroken wilderness, penetrated only by rough logging roads. At rare intervals the eye caught broken patches, thick with birch and maple, which had once been clearings, but the few pioneer settlers had vanished long ago, and now one could paddle half a day without encountering another human being. It had always been a great salmon river, the water closely held under individual leases, ever since a sporting governor general of the Dominion had discovered its possibilities half a century before; although, owing to the lumbering of its watersheds, it had steadily dwindled in size throughout that period and many former fishing camps had been abandoned.

Twenty miles below the Wanic, they passed a pine-covered bluff above a sand spit. “Joe Jefferson had a camp in those trees,” said Donald, pointing to a pile of rotting timber. “I poled him and Grover Cleveland upriver first time they come. Must ha’ been forty years ago. Boy! They was hell on fishin’.”

“And on telling stories?” suggested Mr. Tutt.

“And tellin’ stories!” agreed Donald. “Say, the loggers are tellin’ those same yarns up in the back country yet.”

At noon they beached the canoe to ‘boil’ at a bend beside a foaming stream where the woods had been cut back for, perhaps, a third of a mile, and while Donald built the fire and put on the teapot, Mr. Tutt followed the brook through the alders and undergrowth. All was still under the noonday heat except for the chitter of squirrels or the plash of a kingfisher, dipping in syncopated flight ahead of him. A hundred yards or so from the river, he came upon some overgrown depressions, their bottoms half filled with stones, and farther back, upon some elevated oblong mounds. Poking among the bushes, he stumbled upon a piece of rusted iron half eaten away.

“Must have been some houses in there once,” he remarked to Donald, exhibiting his find.

“Sure,” answered the old guide from where he squatted with the frying pan of bacon in his hand. “This is where the old French village used ‘to be. There’s treasure buried there, if you can find it. I’ve hunted for it many a time when I was a boy.”

“What kind of treasure?”

“Gold, money. A hundred and seventy years ago this was all French country. Ste. Marie des Isles was one of their big towns. When the war with the English come, the inhabitants all got scairt and moved upriver to where they thought they’d be safe. Three hundred came here with their children and everything they had. They settled along that stream and built their houses. Nobody came after ’em and they stayed here for twenty years or so. Then the smallpox killed ’em all off — nary one was left. There’s a pile of money buried in there somewhere.”

“How far are we from Ste. Marie?”

“About eighty miles.”

“And to the Stillwater?”

“Sixty. We’ll get there easy by six o’clock.”

They devoured Charles’ excellent lunch, carefully extinguished the tiny fire, drank a tin cup each of the Bishop’s Madeira, and pushed off again. Each of the old men had a stogy between his lips, while the bottle, with its remaining contents, stood embedded between Mr. Tutt’s legs. He was very happy, peaceful and satisfied. He had killed his limit, he was full of fresh air and good food, the sunlight flecked the ripples on the river, a soft breeze laden with the scent of balsam drew down the gullies — God was in his heaven, all was right with the world. Mr. Tutt unbuttoned his waistcoat, extended himself longitudinally as far as possible and took another drink. This was the life! Those French fleeing from their enemies had selected a good place. A bit cold in winter, perhaps. But what the fishing must have been in those old days! And yet they were all gone!

The sun lowered towards the pine tops in a cloudless sky; the breeze died; amid a silence unbroken save for the gurgle of the river against the sides of the canoe, they were swept swiftly downstream by the current. The shadows of the trees were lengthening across the river as, about five o’clock, they passed the Oxbow — the pool next above the Stillwater, ten miles farther on. A couple of sportsmen were just getting into their canoes for the evening fishing. Then the forest closed about them again, and they entered a long stretch of rapids, where Donald let the canoe run, steering it with his paddle.

“Another twenty minutes and we’ll be at the Stillwater,” he said. “Better set up your rod. There’s half a dozen drops and it’ll take us over an hour to fish it before we get to Micklejohn’s.”

By the time Mr. Tutt had put his rod together and selected his gear, they had shot the rapids and emerged into a smiling farmland, the river broadening to lush meadows high with grass. A mile ahead, below a series of sparkling reaches, lay the railroad bridge. They had reached the famous Stillwater.

Donald shoved the canoe into a shady backwater sheltered by tall trees while Mr. Tutt adjusted his leader.

“There was a town here once too,” he remarked. “Although you’d never guess it. There’s only one family left — Jim Ferguson’s.”

Mr. Tutt looked across the river. “Isn’t that the remains of an old wharf?”

“Yes, but it’s all fallen to pieces. This is a great place for hay. In the old days they used to barge it down to Ste. Marie des Isles. Jim made good money until he was burned out…. The first drop’s over there. It’ll be dark soon. I’d try a Black Gnat.”

While the old gentleman was tying on his fly, there rose from the woods beside them a series of birdcalls more melodious than anything he had ever heard. The notes rose and fell in chirpings, now like scattered drops of crystal, now in silver trills and quavers, followed by the mellow arpeggio of the Canadian thrush, until Mr. Tutt found himself, like Siegfried, staring entranced into the boughs above his head. “Exquisite,” he murmured. “The mellow ousel fluting in the elm!’ What sort of bird is it?”

Donald grinned.

“Burrd! That ain’t no burrd! It’s a woman! “Thrusting his paddle into the water, he silently shoved the canoe around a boulder that cut off the view of the bank fifty yards beyond.

The song ceased suddenly in the midst of a cadenza. A young girl, her black curls tied gypsy-like in a red handkerchief, was sitting on a log with her head thrown back against a rock, her open khaki shirt exposing her white throat. Her brown eyes, startled at their unheralded approach, quickly regained their confidence.

“Hello, Mr. McKay!” she called, in a voice as sweet as the notes she had been uttering.

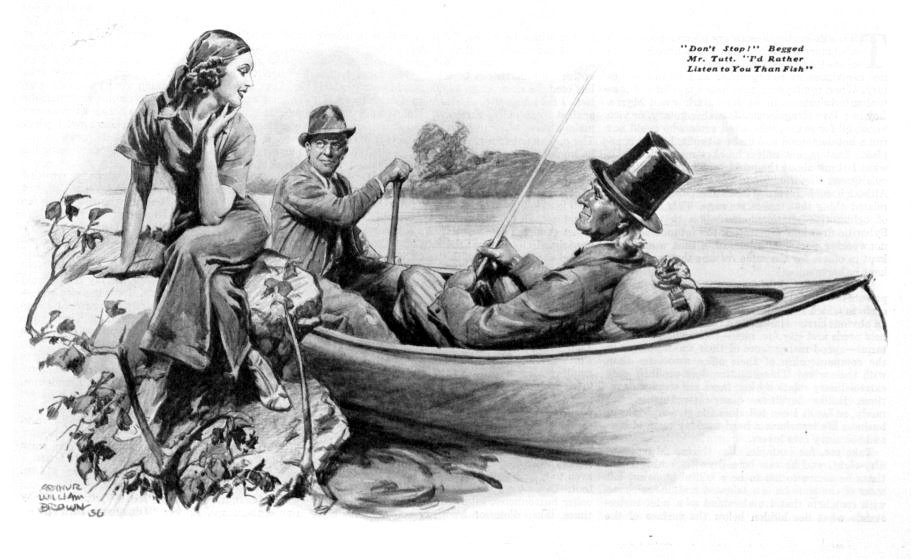

“Please don’t stop!” begged Mr. Tutt. “I’d rather listen to you than fish.”

“He thought you was a burrd!” laughed Donald. “I don’t blame him neither. Many’s the time you’ve fooled me with your veery calls and your warblers.”

“They often answer me at this time of day,” she said. “The thrushes at twilight especially from the grove behind them echoed a golden canzonet. Hark! Do you hear that one?”

“Sure!” declared Donald. “Your mate’s a-callin’ you. Is your dad to home?”

“Yes,” she said. “I’m sure he’d like to see you.”

“Tell him I’ll be over after supper, or maybe before,” answered Donald, with a grimace.

“Are you going to fish the Stillwater? There’s a run on. I saw a lot of big ones on their way up the river from the bridge last evening. Mr. Micklejohn killed a forty-pounder this morning.”

“Who is that lucky child?” asked Mr. Tutt, as, the Black Gnat having been properly fastened, he told Donald to shove off.

“Jim Ferguson’s girl. Clochette,’ they call her. Her mother’s French.”

“A charming creature. She has a wonderful voice.”

“You bet she has. Some folks say she could sing in grand opry.”

“Is she getting proper instruction?”

“Jim’s been sendin’ her to Boston every winter for the last three years. He’s mighty proud of her, I tell ye! We all are, for that matter. But she’s got to give it up.”

“Why?”

“Her dad lost everything he had in the fire. Ain’t even got a house no more. They’re campin’ out in tents this summer.”

The canoe slid out into midstream and floated toward the head of a wide sun-flecked stretch alive with ripples. Donald dropped the killick overboard into the translucent water, here only from three to six feet deep, dug in his paddle to steady the canoe, and Mr. Tutt, lifting his rod, cast at right angles across the stream. The fly settled lightly on the current and was sucked rapidly along and under. Gradually the arc of the line straightened out and he was just about to make another cast when the tip of the rod was drawn heavily downward, the water boiled as from the turn of a propeller, and the line began to run through the guides.

Mr. Tutt struck lightly against a dead weight. Next instant the reel was screaming, the line melting away, humming like a telegraph wire in a sixty-mile gale. He anchored the butt in his belt socket, braced his feet and held tight. It was as if he were connected with a plunging race horse. Far downstream, there was a silver gleam as the salmon broke. The strain slackened momentarily, and the old man reeled in as fast as he could. Then the reel began to scream again, and once more the spool melted away. “He’s headed for salt water!” shouted Donald, pulling the killick.” We got to follow him!” “Hurry!” gasped the old man, pressing down the drag of the reel with all his force. “I haven’t got more than thirty yards left!” Donald dropped the killick into the canoe with a thud, yanked free his paddle, threw his whole weight against it, and the canoe shot downstream. The reel stopped screaming and Mr. Tutt, heaving the rod against his ancient belly, began, foot by foot, to regain his line. But this did not disconcert the salmon, which had evidently made up its mind that it had important business in Ste. Marie des Isles and intended to get there immediately. Aided by Donald’s strenuous paddling and the strength of the current, the big fish towed them along at fifteen miles an hour. The shores slid by. The railroad bridge drew nearer and nearer. The half dozen buildings of Micklejohn’s camp, with the Canadian flag flapping above them, swept into view.

Suddenly the salmon broke again, hurling itself, end over end, high into the air in a rainbow of silver and dropping flat with a crash that churned the surface into foam. Mr. Tutt reeled furiously. The line came in slack, then gradually tightened, running out toward the riffle at the outlet of the pool just above the bridge. The salmon had decided that he needed a rest and that, for the moment at least, he had gone far enough. Swiftly the current carried them toward where the great fish lay skulking in mid channel, until they were almost directly above him. Mr. Tutt had regained most of his line and was ready for another dash — to Anticosti, if need be.

“Keep your line tight, or he may work free,” warned Donald. “He’s anchored there. Got his head agin’ a rock prob’ly.”

It was too deep to reach the salmon with a gaff or otherwise to dislodge him. Neither was it possible, in the face of the current, to maintain their position. So, while Mr. Tutt continued a steady strain upon the line, Donald swung the canoe inshore and held it firmly with the paddle.

“He’ll get sick of it ‘fore long,” he said. “We’ve got to be ready to start whenever he does.”

Mr. Tutt sat there, the butt of the rod against his diaphragm, his eyes upon the point where his taut line entered the water seventy feet distant, waiting for something to happen. It did.

There was a scattering of gravel from the bank behind them, the sound of heavy breathing and, before the old man could turn his head, a hunting knife held by a brawny hand descended and severed his line: “Ping!” Mr. Tutt, thus unexpectedly released from frontal strain, was only saved from falling backward into the canoe by the gunny sack behind him.

“Jumping Jehosaphat!” he ejaculated, grabbing at his stovepipe. “What’s happened!”

The owner of the knife, a huge bearded man in waders, stood lowering at him beneath shaggy black eyebrows.

“Get off my land!” he ordered. Donald drove the canoe back into the river.

“And off my water!” yelled their assailant.” Get off — and stay off!”

Mr. Tutt was trembling with outraged indignation. The line attached to the salmon had vanished into oblivion. No doubt, it was already on its way to Ste. Marie des Isles.

“Micklejohn,” muttered Donald shortly, squirting a thin brown stream in the direction of the shore.

“The man we expected to spend the night with?”

“We didn’t. Maybe you did. I’ve known him longer than Mr. Norton has.”

“That fellow the president of a railroad!”

“He owns it,” explained Donald. Micklejohn, having sheathed his hunting knife, was seated cross-legged upon the bank, watching them. “Get along!” he shouted. “Beat it!”

“Mr. Micklejohn” said Mr. Tutt raising his voice so that it would carry across the intervening distance, “You have made me lose a brand-new twelve-foot double leader and a hundred and fifty yards of line. I shall expect you to pay for them.”

“Like hell! They were forfeit under the statutes!” shouted Micklejohn. “I could have kept your rod too. I’m going to telephone the warden and lodge a complaint against you for trespass. I’ll teach you that we have laws in Canada.”

Then Mr. Tutt, eminent member of the New York Bar that he was, lost all his dignity. They were drifting rapidly downstream toward the bridge, and maybe his old voice was tired. Perhaps he believed that action spoke louder than words. At any rate, with or without excuse, the distinguished Mr. Tutt placed his antique thumb to the end of his long nose, wiggled his bony fingers at Mr. Micklejohn and gave vent to an inelegant sound known as “the raspberry,” or “Bronx cheer.”

By this time, it was nearly dark and a cold wind was blowing up the river.

“Want to go on to Ste. Marie?” asked Donald.

“It’s twenty miles. Supper would be over before we got there. And I’d rather meet the sheriff by daylight,” answered Mr. Tutt. “Where else can we go?”

“Jim Ferguson would put us up.”

“Okay. Let’s go there.”

A campfire in front of a small group of tents threw a cheerful gleam across the river, and it took Donald but a few moments to reach the opposite shore, where the genial Ferguson, his pleasant- faced French wife and Clochette welcomed them on the beach. A full moon was rising above the pines as they finished their modest but savory meal of potato soup, broiled salmon steak and peas, fresh strawberries and black coffee. Mr. Tutt produced what was left of the Bishop’s bottle of Madeira, and Clochette, without a trace of self- consciousness, her voice rising high and clear, sang for them while they smoked — boating songs of the voyageurs, Scottish border ballads, and chansons of old France, handed down in her mother’s family.

“Do you know Nanette?” she asked. “Nanette went down to bathe. That is what I’d been doing when you saw me this afternoon.”

“And Mr. Tutt thought she was a burrd, Jim!” chuckled old Donald; so Clochette laughed and sang A in Claire Fontaine, because it was about a bird.

“That’s what she should be called’ Nightingale’!” averred the old man. “And, as the song says, I shall never forget her either!”

While the women washed the dishes on the shore, Jim Ferguson told the story of Stillwater and the loss of his home. Years ago, it had been a thriving town of lumbermen and farmers, surrounded by cleared fields for a quarter mile back on either side of the river. Five generations of Fergusons had lived where the tents were now pitched. There had been a school, post office, a couple of stores, and daily a small river steamer had come up from Ste. Marie des Isles, bringing mail and supplies and keeping the settlement in touch with the outside world. Then the small- pox had ravaged the community, the logging industry had declined, the young folks had moved away, until at last the Fergusons were the only ones left.

As a partial compensation, Jim had been able to acquire a large tract of abandoned land for almost nothing. There was a good market for his hay, which he at first had barged down to the coast, and then, after the railroad had come through, had shipped by freight. He prospered, saving enough to add each year to his machinery tedders, mowers and sweep rakes, building barns in which to store his crop until he could sell to best advantage, and installing his own press to bale the hay for transportation.

He had married a girl of French descent and Clochette was their only child. During the winters they moved down river to Ste. Marie des Isles, so that she could go to school. When they discovered that she had a voice, they had sent her to Boston for training. Then the preceding summer, just at harvest time, when two of the barns had been filled and the rest of the crop was in cocks ready to be carried, a fire had started near the railroad track and, sweeping across the fields, had destroyed everything, including their dwelling house. Not a building had been left, and the insurance had been only sufficient to re-equip them with tents, canoes and a few tools, and keep them going through the winter.

The fire had probably been started by a spark from the Whooper, and the company was clearly responsible. Jim had brought suit for $25,000 through a firm in Ste. Marie des Isles, but his lawyers advised him that the evidence, though morally convincing, might be held insufficient to sustain a judgment, since there was nothing, from a legal point of view, to exclude the possibility that the fire had started through the carelessness of some fisherman, hunter or river driver. So they were going to have to start all over again, and Clochette would have to give up her musical career.

“Doesn’t Micklejohn know that a spark from one of his engines destroyed your property?” demanded Mr. Tutt.

“Sure he does. Everyone knows it. It’s true that the fire started over fifty yards from the track, but there was wind enough to carry a spark even farther than that. Besides, there weren’t no fishermen anywheres round here except Micklejohn. The skunk wouldn’t ha’ been above setting it himself!”

“You mean that he might have burned you out purposely?”

“Just what I mean. He’s wanted to get rid of me for years, so as to have all the fishing on both sides for himself. Y’see I was here first and had my quarter mile of shorefront before he located his camp over there and bought up all the land there was left.” Mr. Tutt had a momentary vision of a black-bearded man with the hunting knife in his hand.

“He’s not a good neighbor?”

“We don’t speak.”

The old lawyer sat smoking by the dying embers of the fire long after all but Donald had gone to bed. “Is everything Jim said true?” he asked.

“Honest to God!”

“How long has Micklejohn been here?”

“Eleven years. He bought soon as he got to be president of the road.”

“When was the bridge built?”

“Nineteen nineteen — sixteen years ago.”

“Was the town here then — Stillwater, I mean?”

“Sure! Quite a settlement. My sister lived here with her husband. The smallpox come in 1920. They didn’t discontinue the post office until a couple of years later.”

“How long since the steamer stopped running?”

“Same time.”

“Fifteen years?”

“Just about.” Donald got up, stretched, and spat into the fire. “If we’re to take the Whooper at five tomorrow mornin’, what time shall I wake you?”

Mr. Tutt stared across at the bead of light that marked the presence of Local Public Enemy No. 1.

“You needn’t wake me,” he said. “We’re not taking the Whooper. If we go to Ste. Marie tomorrow, it will be by canoe.”

“I reckon I’ll turn in anyhow,” answered Donald. “You mayn’t be tired, but I be!”

The moon rode higher and higher, a silver dime in a starless sky, azure as by day. Mr. Tutt could see every stone upon the beach, the patches on the bottom of the overturned canoe, the gunny sack containing his personal belongings; could even read the label on a near-by tomato can. Opening the sack, he removed a bug light, put it in his pocket and, lighting a fresh stogy, he lay flat upon his stomach and peered down through the ties.

“H’m!” he said to himself, observing that the keys swung clear of the buttress by about six inches where it emerged from the surface. Getting to his feet, he untied the string and repeated the process at the other end of the draw.

“H’m!” he repeated in a tone of satisfaction.

Bug light in hand, having returned the string and key ring to his pocket, he examined the joints of the antiquated machinery, rusted and eaten away by the wind and rain of thirty years. The bolts in one counterweight had disappeared; the lever operating the trunnion was immovable, frozen, as if welded.

“H’m!” he ejaculated a third time.

“If I haven’t got that so-and-so, I’ll eat my tall hat.”

He was aroused by the crackling of a fire outside his tent and the pungent smell of bacon. From the beach below came the warble and trill of Clochette’s limpid coloratura:

“Au beau Blair de la tun’ m’en allant promener — ”

“How the devil did you know that?” he demanded as she ascended the bank, a pail of water in her hand.

“Know what?”

“Oh, never mind,” he answered. “What time is it?”

“Six o’clock. Didn’t you hear the Whooper go by an hour ago?”

“Whooper! It would have taken Big Bertha to wake me up. I slept the sleep of a just man. Tell Donald to get the canoe ready. I’m going to Ste. Marie as soon as I’ve had my breakfast.”

“Are you leaving us for good?” she asked regretfully. “I hoped you’d spend the day with us.”

“Oh, I’ll be back, Nightingale! Never you fear!”

“I’m sorry for Mr. Micklejohn, I’m sorry to give him pain, but a hell of a spree there’s going to be When Tutt comes back again!”

The president of the Canadian Seaboard & Gaspe, smoking his after breakfast cigar on the veranda of his camp, saw the canoe with its tall hatted occupant skirt the opposite shore and disappear under the bridge.

“I taught that silly old ass a lesson, all right!” he gloated, for he had feared that the trespasser might stay on and fish the quarter mile of water he did not control. His worst nightmare was that Ferguson might build a sporting camp and thus destroy the practical monopoly of the Stillwater which he now enjoyed. But the farmer was too busy haymaking to do any fishing, hence Micklejohn, week in and week out, had the whole ten miles to himself.

It was another sparkling day and the president of the C. S. & G., having killed a couple of thirty pounders, was paddling back for lunch when the noonday silence was unexpectedly broken by an untoward sound — a sound that President Micklejohn had never before heard in that locality — the unmistakable whistle of a steamer just below the bridge.

“Toot, toot, toot! Toot, toot, toot!” “Damn his eyes!” he cried.” That fool will drive every salmon ten miles upriver!”

“Toot, toot, toot! Toot, toot; toot!” snorted the unseen visitor impatiently. “What in hell can that fellow want?” exclaimed the railroad man, for never once in the entire eleven years of his occupancy had he seen a steamboat on the Santapedia.

Then, as if with the deliberate intention of demonstrating its nuisance value, the whistle broke into a shrill, continuous and never-ending scream.

“I’ll fix that!” shouted Micklejohn in wrath, climbing the embankment.

A stubby little tug was holding herself in the channel, nosing the draw, tooting her head off.

“What are you making such a noise about?” he yelled above the racket. Then, to his amazement and disgust, he observed that the Silly Old Ass in the tall hat was sitting cross-legged on the roof of the pilothouse, puffing a curious looking, rat-tailed cigar, while on the deck below stood the sheriff of the county and a tall man in a gray felt hat whom Mr. Micklejohn did not recognize. Behind them were a group of strangers in mufti. Since the embankment was but twenty feet above the river, the entire party, including Mr. Micklejohn and Mr. Tutt, were in fairly close juxtaposition.

“Open your draw!” called the captain of the tug from the pilothouse window.

“What are you talking about?” answered the president of the C. S. & G.

The tug suddenly stopped tooting. “Let us through!”

“I’m no draw tender!” replied Micklejohn furiously.

“If you ain’t, where is he, then?” asked the captain.

“There isn’t any. This draw hasn’t been used in the last fifteen years.” The tug had laid alongside the bridge, and a deck hand now made it fast to the abutment. The tall man stepped forward.

“Excuse me,” he said. “I’m Sir Douglas Hartley, judge in Admiralty of the Exchequer Court for this district. This gentleman, through his local counsel, has made an informal application before me, in chambers, for a mandatory injunction to abate a nuisance and to compel the Canadian Seaboard & Gaspe Railroad to maintain its draw in this bridge in accordance with its license. He offered — very fairly, I must admit — since he does not wish to take the railroad company by surprise or to put you to any greater inconvenience than is necessary, to facilitate the proceeding by bringing the court here to see for itself — ”

“Birnam wood be come to Duns inane’!” chirped Mr. Tutt.” — what the actual conditions may be,” continued Sir Douglas, faintly smiling.” I take it that I am addressing Mr. Cyrus Micklejohn, president of the railroad?”

“You are,” snapped Micklejohn. “But I’m not here in my official capacity.”

“It would appear then that there was nobody here in an official capacity?” suggested Sir Douglas mildly.

“There has never been any reason why there should be.”

“Your Honor,” said Mr. Tutt from the roof, “this is a navigable stream and I have hired this steamer to take me to Stillwater. I want to go there. I insist on going there!”

“Well, you can’t go there!” roared Micklejohn.

“You’ve got a draw; open it!”

Mr. Micklejohn stared haughtily at the rusty levers and trunnions and the dilapidated counterweights.

“Nonsense!” he remarked.

“Won’t it work?” blandly inquired the sheriff.

“I — I don’t know! And I don’t care!” retorted Micklejohn.

A businesslike-looking young man stepped forward from the group behind the judge.

“My name’s McAvoy,” he said. “I’m Provincial Bridge Engineer. I have two of my assistants here. Suppose we take a look at it.”

They climbed up the abutment and examined the draw.

“You’re going to have a hard time opening that thing,” declared Mr. McAvoy. “The machinery’s all rotted to pieces, the iron has frozen, and, besides, the piers have sagged so far out of plumb that I don’t believe it would work anyway.”

Micklejohn took out his handkerchief and rubbed his forehead.

“Well,” he growled, “this is something I shall have to turn over to our law department.”

“I took the liberty of having my clerk telephone to your attorney, Mr. Cameron Hall, in Cardogan,” interjected Sir Douglas. “He said he’d order a special and come down.”

“Meanwhile, how am I going to get to Stillwater?” pressed Mr. Tutt. “Stillwater! There isn’t any Stillwater!” snorted Micklejohn.

“Oh, yes, there is!” replied the old lawyer.” Stillwater continues to be a geographical and legal entity, even if it is functus officio.”

“There aren’t any people living there!”

“I know of at least four,” answered Mr. Tutt. “Yourself, Mr. and Mrs. Ferguson and their daughter.” “This is all hocus-pocus!” hotly protested Micklejohn. “Ferguson doesn’t want to use the draw! And I’m sure I don’t!”

“Yes, I do!” shouted Ferguson, sticking his head out of the pilothouse window.” I want to go right up the river.”

Mr. Tutt descended from the roof of the pilothouse, Micklejohn glaring at him the while. The president of the C.S. & G. had begun to wish he hadn’t adopted such strenuous tactics with the Silly Old Ass.

“Your Honor,” said Mr. Tutt, landing on the deck, “I appreciate that this isn’t either the time or place for a legal argument, but since you’ve been so amiable as to lend your presence to an attempt at an adjustment of what might otherwise prove a long-drawn out and expensive litigation, I beg to assure you most emphatically that there is no hocus-pocus about it whatsoever. Under the Canadian Railway Act of 1919, no railroad company may build a bridge over any water, river, stream or canal so as to impede navigation, no matter how slight, except with the approval and subject to the directions of the Board of Railway Commissioners and the Department of Public Works. That authority, under the powers delegated to it by Parliament, approved the plans submitted in the year 1919 by the Canadian Seaboard & Gaspe for a drawbridge over the Santapedia at this point, on condition that it be operated as such. The condition having been violated, the authorization is void and the bridge becomes a public nuisance, which can be abated.”

“Rot!” bellowed President Micklejohn. “We don’t have to keep a man sitting here if the draw is never used.”

“You’re obliged to keep your draw in operation or your license lapses. The law says, ‘It is not the use which has been made of the water, but the use which may be made of it, without a change of conditions, that determines its navigability.”

“There has been a change,” declared Micklejohn sullenly. “There was a town here when the bridge was built, and it isn’t here now.”

“The phrase ‘change of condition’ in the law refers not to the number of inhabitants but to the navigability of the stream. So long as there is a single landowner upstream beyond the bridge, he has a right to insist on the railroad complying with the conditions under which it received its authority to build. It is a riparian right inherent in his ownership of the land.”

At that moment a distant whistle echoed through the forest, the rails began to hum, and presently an engine dragging a single day coach came thundering down the track and stopped at the other end of the bridge. Half a dozen men piled out, among them Cameron Hall, K. C., the railroad’s chief legal adviser, from Cardogan, the capital of the province. With him were two of the company engineers. By this time everyone from the tug, including Sir Douglas, Mr. Tutt and the sheriff, had ascended the embankment.

“Of course, I’m here purely ex officio,” said Sir Douglas. “Don’t bother about me. I’m enjoying this little excursion immensely. Suppose I take a walk and give you gentlemen a chance to get together?”

While the company engineers looked over the bridge, Cameron Hall, K. C., conferred with Micklejohn, after which they all went into a huddle at the other end of the bridge.

“May I speak to you a moment, sir?” at length said the lawyer, a dignified but kindly looking man, advancing toward the draw.

“With pleasure, so long as your client doesn’t share in our conversation,” answered Mr. Tutt. “How about a stroll down the tracks?”

They picked their way along the ties until they reached the opposite shore, where they sat down in the hot sunlight at the same spot where Mr. Tutt had climbed up the night before “au beau Blair de la lun’.”

“I’ve often heard of you, Mr. Tutt,” said Hall, K. C. as he accepted a stogy, “but somehow I never supposed you really existed. Certainly it’s a great surprise to meet you under circumstances such as these. What do you want us to do?”

“How much do your engineers say it will cost to install proper piers and rebuild the draw?”

Hall squinted at him over the end of his stogy.

“Do you trust me?”

“I know an honest man when I see one.”

“That compliment will probably cost me about fifty thousand dollars!” chuckled Hall.

“I could have found it out for myself. In fact, I have, rather roughly — only my estimate is thirty-five thousand.”

“I, too, know an honest man when he tells me a thing like that.”

“And that will probably cost me about ten thousand,” said Mr. Tutt significantly. “How shall we work it?” Hall, K. C., looked across at the ruined barns by the little group of tents.

“How much damage does Ferguson claim against the company on account of his fire?”

“Twenty-five thousand dollars.”

“Our engine didn’t set it, you know.” Mr. Tutt shrugged. “If not, I know who did.”

“I see that we agree — in principle. All right, but, as Eden said to Hitler, this isn’t an ultimatum. Suppose we settle the damage suit for twenty thousand and give Ferguson five thousand more for all his riparian rights, including his fishing. In that case, naturally, he’ll have to sign a special release waiving the discontinuance of the draw.”

Mr. Tutt shook his head. “There will be no surrender of any fishing rights whatever. That is an ultimatum!”

“Very good. I was instructed to ask for them, that’s all. Now I’ve done it. How about twenty-four thousand for the fire and a thousand for the bridge release?”

“Not enough!”

Hall, K.C., looked pained. “There is one more condition which I make as a sine qua non,” said Mr. Tutt sternly.

“Go easy on us!” begged Hall. “What is it?”

“Upon the signing of the papers, Micklejohn is to deliver to me one new twelve-foot, mist-colored double leader, two hundred yards of the best salmon line you can buy in Cardogan and — ”

Hall’s eyebrows had drawn together. “What the devil!” he seemed to be saying.

“Yes, and — ?”

“And his hunting knife.”

“That’s a queer one!” ejaculated the K.C.

“Otherwise the C.S.&G. can rebuild the bridge!”

Just then from the neighboring grove came a high, sweet song like that of a bird.

“What a beautiful voice!” exclaimed Hall in admiration.” It’s like what I’ve always supposed a nightingale’s would be!”

“Yes” Nodded Mr. Tutt. “The C.S.&G. isn’t paying for a fire, but for a girl’s career… well! Is it a deal?”

“It is” answered Hall, and shook hands.” Now I’ll go and give my most unpleasant client the glad tidings.”

“And be sure to tell him that I’ve discovered that they have laws in Canada.” Said Mr. Tutt

The old man climbed down the embankment and walked over to the grove. He hated to return to the city. New York was all right, but the woods were better. He’d spend all winter planning how to get back to them. His old house on 23rd Street, with its comfortable library and sea-coal fire — even with Miranda’s cooking — would be very lonely. It was hard to say goodbye.

Clochette was sitting against a tree, singing her heart out. “Hello, Mr. Tutt!” she cried. “What are all those people doing on the bridge? And why is that tug there?”

“It’s taking me back to New York,” answered the old man, looking down at her tenderly.” Would you like to go with me, Nightingale?”

Featured image: Arthur William Brown