Considering History: Tillie Olsen and the Challenges and Inspirations of Motherhood

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Motherhood is often presented in clichéd and simplified terms, in greeting-card platitudes and ideals. Its realities can be far more complex and challenging, especially for single mothers, mothers living in poverty, and all those whose situations do not match up with mainstream images or narratives. As one of the first feminist writers, Tillie Olsen gave voice to these more complex versions of motherhood in her short stories. Her writing, nearly 60 years later, still has a powerful story to tell.

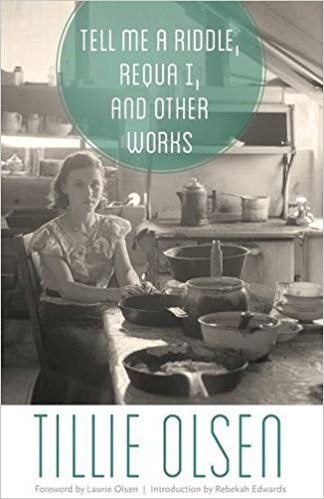

Olsen’s “I Stand Here Ironing [PDF],” the first of four short stories collected in her debut book Tell Me a Riddle (1961), offers one of American literature’s most raw and realistic depictions of motherhood. In the story, Olsen’s unnamed narrator struggles to answer a concerned teacher’s questions about her teenage daughter Emily, reflecting on her time as a Depression-era single mother while performing the titular domestic task late at night. At best, the narrator had to leave Emily with others while she worked or sought work; too often, Emily was removed to foster homes or state facilities when the narrator could not provide for her. Although the narrator has since remarried and Emily now has a stepfather and step-siblings, she worries that those childhood circumstances have profoundly damaged her daughter, concluding with a fraught plea: “Only help her to know—help make it so there is cause for her to know—that she is more than this dress on the ironing board, helpless before the iron.”

Olsen’s story is at least as much about her narrator-mother character as about Emily. Olsen herself composed the story’s first draft while ironing. The narrative mirrors her own autobiographical story along with those broader and more universal themes of motherhood. Indeed, Tillie Olsen’s life and career reflect both the challenges and inspirations of motherhood.

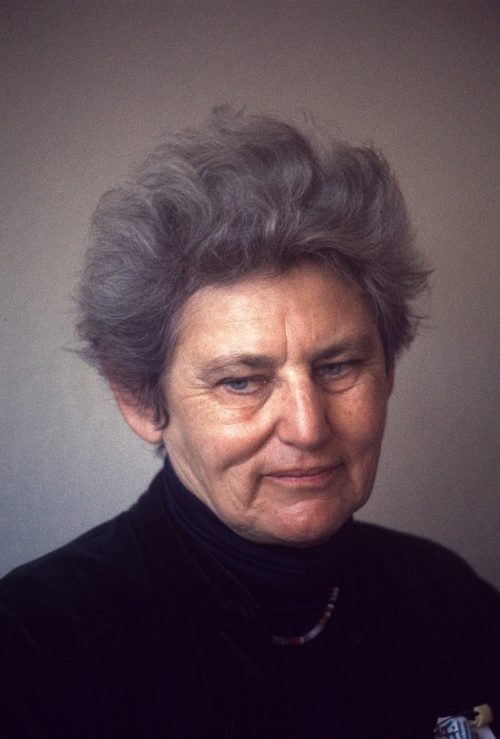

Born Tillie Lerner in Nebraska to Russian Jewish immigrants, Olsen (1912-2007) dropped out of high school at 15 to work and support her family, and was a union organizer and socialist activist by 20. At that age she also began writing her first novel, Yonnondio. When an excerpt of the opening chapter was published in the Partisan Review in 1934, Random House offered her a contract for the entire book sight unseen. She had her first daughter, Karla, at the age of 20, and the challenges of single motherhood in the Depression era made it impossible for her to continue work on the novel. Over the next decade she would meet and have three more daughters with fellow activist Jack Olsen, and in the process dedicate herself even more singularly to motherhood and household work (although she did publish a number of articles on her activist efforts).

It was only in the late 1950s, with her daughters grown and her family situation more stable, that Olsen was able to return to creative writing. “I Stand Here Ironing” was her first completed short story, and that starting point is far from coincidental: although she argued that a friend’s situation (in which the friend was questioned in court about her fitness as a single mother when her teenage son was caught drinking beer) provided the story’s origins, it clearly transformed in the writing over that ironing board into a deeply autobiographical reflection on her own early years as a Depression-era working single mother.

We were poor and could not afford for her the soil of easy growth. I was a young mother, I was a distracted mother. There were other children pushing up, demanding. Her younger sister seemed all that she was not. There were years she did not want me to touch her. She kept too much in herself, her life was such she had to keep too much in herself. My wisdom came too late. She has much to her and probably little will come of it. She is a child of her age, of depression, of war, of fear.

From that story and the three others collected in Tell Me a Riddle, a debut book released when Olsen was nearly 50 years old, she built a frustratingly sparse but still strikingly diverse body of published work over her remaining few decades. She was finally able to return to and finish her novel, releasing Yonnondio: From the Thirties in 1974; the subtitle subtly reflects and comments upon the four-decade gap between the Partisan Review excerpt and the novel’s publication.

In her next book she engaged directly and analytically with such gaps: Silences (1978) analyzes silent periods in authors’ lives and careers, with autobiographical reflections woven into an impressively thorough account of historical and contemporary examples. And in two subsequent edited works, Mother to Daughter, Daughter to Mother: Mothers on Mothering: A Daybook and Reader (1984) and Mothers & Daughters: That Special Quality: An Exploration in Photographs (with Estelle Jussim, 1987), Olsen and her collaborators explore the role that had contributed so fully to her own multi-decade literary absence.

Yet while motherhood had unquestionably presented such challenges and limits to Olsen’s professional writing career, it also could be said to provide a vital inspiration for that career when it blossomed so potently in the second half of her life. Without minimizing all the work that could have been written in the decades between her Random House contract and Tell Me a Riddle, it’s nonetheless the case that each of Olsen’s books offers unique contributions to late 20th century American literature and culture. Her works focus both on the roles and realities of motherhood in all their complexity and on the intersections between that identity and women’s creative and professional careers and lives.

Tillie Olsen’s works confront those realities at their most raw and affecting. Yet they also include, and in their very existence illustrate, motherhood’s inspiring potential and effects. All good reasons to read Tillie Olsen for this Mother’s Day.