North Country Girl: Chapter 33 — The End of Childhood

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. This is the last chapter in the series.

Michael Vlasdic’s mother, the German professor, was always obliging; that summer, she taught a full load of classes, leaving Michael’s house delightfully parent-free for hours and hours. I loved Michael. I never wanted to leave his arms. To be with him, I had spent the past six months fretting over my personal monthly calendar — is it safe to have sex this day? The day after? After every “safe” day I was convinced I was pregnant and doomed right up until my trusty body proved otherwise.

Now the 60s made a further encroachment in Duluth: Planned Parenthood came to town. Until then, the only doctor I knew was my pediatrician, Dr. Bergman, who had seen me in my white Carters undies and examined me for pinworm.

The girl grapevine went into full swing. “I heard if you’re sixteen you can get birth control at Planned Parenthood and they don’t tell your parents,” said a wide-eyed Wendi Carlson. I was one of their first customers. I was so desperate to have as much sex as possible with Michael, to be free of the tyranny of the menstrual cycle, that I turned up at their downtown office and bravely asked to see a doctor. I was ushered into the exam room of a very nice woman doctor, another thing I had only seen on TV. I cringed through my first pelvic exam, even though the nice doctor complimented me on my “textbook cervix.” When my legs were back together and on the ground, the doctor handed me a prescription that read “To regulate flow” and told me to come back in a year.

I had drugs and Michael and his empty house and no more worries about being knocked up. It was a fun summer. I tried to be mindful of the time on my work day when I had to punch in at The Bellows at four to make sure that those idiots who showed up for a steak dinner at five would have a fresh crisp salad. But we were insatiable. One afternoon, as I felt Michael poking me in the leg, ready for a third bout, I raised my kiss-swollen face up off the bed and saw to my horror that it was a quarter to four. Michael was pulling me down; of course he didn’t understand why I had to be at The Bellows on time. Unlike everyone else I knew, Michael did not have a summer job. He refused on principle to work for the man. “Who cares if you’re a few minutes late?” he grumbled. “It’s not like you’re doing anything important.”

The real German, I was determined to keep the salads running on time. I threw on my clothes, not bothering to wash. Michael grudgingly offered to walk me the ten minutes down to The Bellows. Walk? I need to go at a quick trot to get there on time.

I was two blocks away from the restaurant, waiting at the corner to cross the busy-for-Duluth Superior Street. Traffic finally slowed as a bus pulled up and stopped. I started to dash across the street, certain Michael was beside me. But he had seen the car behind the bus veer left to go around it. I did not. I felt a bang and landed on the hood of a cab, looking into the horrified face of the driver. The next thing I knew I was on the ground and Michael was standing over me, red-faced and sobbing, as the bus driver and the cab driver both shot out of their vehicles. I assured everyone I was fine, and got up to continue on to work. No one was going to let that happen; I was guided over to the curb by several hands and forced to sit. Soon an ambulance showed up, and even though I was still protesting — who would make the salads and defrost the shrimp? — I was loaded inside. Before they shut me in, I called over Michael, who bent over me for my last words, which were to call The Bellows and explain that I had been hit by a car.

At St. Luke’s Hospital I was X-rayed and palpitated and asked if I knew the name of the president and what day of the week it was. I did, and nothing was broken; when my father showed up (who had called him?) they were ready to release me. I pulled my jeans on over the yellow and purple bruise that covered my left leg from knee to hip, pushed myself off the examination table and fell over. I could not put any weight on that leg.

My father drove me home in silence, then helped me onto the living room couch, the first time he been in the house since the day he left. He stayed until my mother finally bustled in, furious at having been summoned home by some stupid kid thing, and even angrier that my dad got to act the part of the responsible parent. As soon as he was gone, she lit in to me: how in the world does anyone get hit by a car? Couldn’t I see it coming? She was also suspicious of where I had been all that afternoon; it was July, I was not doing homework at Michael’s house.

In a few days I had recovered enough to lean against the big stainless steel sink at The Bellows, peeling shrimp and cracking oysters; and to figure out ways to make love on Michael’s narrow bed without his weight, however slight, on my injured thigh. Michael kissed the bruises, fading into less corpse-like shades, and told me how sorry he was, how he had just been about to warn me when I went teacups over kettles on the hood of the taxi. He did not feel badly enough to go out and look for a job himself; I kept working and kept spending my paycheck on drugs.

Summer ended and that golden age of youth, senior year, started. Saturdays were still reserved for Michael and acid, but every Friday I was with my friends in the White Delight, cruising up and down Duluth, in search of where the action was. Our senior year parties became wilder, more abandoned, with more booze, more drugs, and dozens of kids in various stages of intoxication. We huddled around house-sized bonfires on the lake shore, tossing empties into the flames and laughing hysterically at nothing. We smashed into the Anderson’s basement; the crescendo of “Stairway to Heaven,” still new to our ears, made conversation impossible and unnecessary.

There were a few casualties. Betsy James had a fight with her boyfriend, and took off on his motorcycle; he found her a block away pinned under it, with a broken leg and a large patch of her skin left on the asphalt. Craig Whiteman, one of East’s few greasers, polished off a six-pack of Grain Belt at a party and accepted a dare to break into old lady Congdon’s mansion. No one knew that Dorothy Congdon was a champion skeet shooter who slept with a loaded shotgun beside her.

My band of sisters grew closer together as high school graduation neared. We had forged a sacred bond, at a time when our hearts and souls were soft and malleable, and our feelings strong and blood hot. Our friendship was built on years sharing our teenage loves and disappointments, laughing, drinking, sometimes crying, and always caring deeply. We knew that college and jobs, new lovers and new friends, would soon disrupt the centrifugal force that kept us together, though we vowed not to let that happen.

Michael and I also believed with the fervor of a religion that we were destined to be forever together, the fever dream of first love. But while I had despaired every time my period was half a day late, Michael romanticized the possibility of us having a baby. He longed for an addition to his tiny two-person family and got all misty-eyed listening to Crosby, Stills, and Young’s “Our House.” We shared a dream of a small apartment in Minneapolis, filled with sex and drugs, college textbooks and cats, where we would fall asleep in each others’ arms, but my dream definitely did not include a baby.

While my heart was sworn to Michael, the rest of me was stirring with other desires. Being safely on the Pill turned a key in my mind, which opened up a new world of sexual possibilities. Emily Dickinson wrote “There is no frigate like a book, To take us miles away,” and for years books had been my only escape from my stolid small town life and boring middle-class family. I could get lost again and again in the exploits of Bilbo Baggins and Gandalf, Arthur and Merlin, Dorothy and Alice, and all those other plucky young heroines. Then I discovered that drugs could shanghai my mind, transport me to different realms. Now I realized that there was another vehicle that could take me away on adventures: my own body.

I started looking at other boys with a hungry curiosity. What would it be like having sex with them? How would they smell, how would they touch me? Would the sex be better or just different? And maybe just different would be exciting enough. According to Time magazine, which still made its weekly appearance in our mailbox, the sexual revolution was in full swing. I was a willing recruit to any revolt. Even my own mother, still pretty at thirty-seven and post-divorce slim, had seduced a former stalwart of the Catholic Church and father of six, and was busy trying to get him to dump his wife and marry her.

The culture, my body and mind, and the nice people at Planned Parenthood were all encouraging me to expand my sexual horizons; the only reason not to was that Michael, my sensitive, moody lover, would be hurt. So I never told him about the others. I was callow and callous, and from a distance of many years, I can see that I was not the adventuress I thought I was — just an asshole.

There was Jonathan, who had been making me laugh since seventh grade advanced math. He was a behind-the-scenes stagehand for all our aspirational high school plays, painting flats, adjusting the lights, and cracking up everyone in earshot. The plays our high school put on were ancient chestnuts, chosen for their ability not to offend anyone: starting with “My Three Angels” (misspelled on every poster as “My Three Angles”), about a trio of fugitives from Devil’s Island, through “You Can’t Take It With You,” with its cast of thousands.

That play provided my one chance for glory on the stage. I had been trying out in vain for a part in one of East’s plays since I was a sophomore. Our creepy drama teacher Mr. Canfeld had given every single leading role for the past three years to milquetoast Grace Myers; rumor had it that she let him feel her up. On my ninth audition for him, Mr. Canfeld felt sorry for me, ignored my lack of acting ability, and cast me as Olga, the White Russian countess, who shows up in the final act to deliver her three lines. After our second and closing performance, cast and crew gathered in somebody’s parent-less house for one of the epic theater parties. Drunk and high, Jonathan and I were talking, then giggling like lunatics, then kissing. We locked ourselves in a bathroom so we could take some of our clothes off. As I had hoped, it was different and it was fun, like taking a roller coaster ride together. Miraculously, Jonathan and I became better friends.

One sub-zero Saturday night, Michael Vlasdic and Needle both sick with the flu, Roger and I ended up alone, driving aimlessly around Duluth in search of a party. Sitting next to him on the front seat, like boyfriend and girlfriend, I realized I liked his craggy profile and scooted over a little closer, feeling a pleasurable tingling. When Roger put his arm around me, a bolt shot through my body to where his hand rested on my shoulder; we both felt the electricity through our winter woolens. Without saying a word, Roger steered for Skyline Drive, the favorite parking place for Duluth teens. We stretched out as much as we could in the back seat and committed our double betrayal, he of his friend, me of my soulmate. When we were done, we felt a bit bad and swore it could never happen again. But it did, and it was furtive and secret and thrilling.

I had always had a little crush on handsome, sleepy-eyed Jack France, who showed up occasionally at Open Mind meetings to read his angsty poetry. He was like me, a flitter among groups, a smart athlete who got high. Now I side-eyed him in Mr. Burrows’ class, where he sat alone in the back, gazing out the window. I wondered what it would be like to kiss him.

I found out on a yellow Bluebird bus making its bumpy way back from Telemark, Wisconsin, after a day of spring skiing. Nancy Erman had organized a school ski trip, one of the last hurrahs of our senior year. We skied stripped down to sweaters and blue jeans, luxuriating in the sunshine that was almost warm. There was such joy in the day, in our forever young bodies that we sent hurling recklessly down the slopes, again and again, until the lifts slowed and stopped and it was time to go home. Jack and I had skied together that day, and it didn’t take much wrangling on my part to end up sitting next to him on the tot-sized school bus seat. Jack shook out a package of Lucky Strikes from his pocket and lit a cigarette. Then we kissed. I thought I was the world’s best, most experienced seventeen-year-old kisser; I was knocked for a loop. Jack’s kisses shrunk the entire world down to the two of us, nothing but slightly chapped lips and gentle exploring tongues and the taste and smell of tobacco which reminded me of fall’s burning leaves. On the bus, in parkas and long johns and snow-soaked Levi’s, there was nothing more we could do than kiss, and the kisses were everything.

Jack and I never went any further. For years, every time we ran into each other, Jack and I would end up in dark corners where we shared those deep soulful kisses, sometimes for hours, until he took off one autumn on a solo cross-country bike trip to Seattle, where he leapt off the George Washington Memorial Bridge.

Being with Jonathan, Roger, and Jack was fun, it was sex with no agenda, no strings attached. It wasn’t about love, or negotiating a relationship, or even about my desperate desire to be thought of as pretty and sexy and cool.

I was beginning to regret the plans that Michael and I had made, that we’d go off together to the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis and live happily ever after. I was going to spend my first year in a dorm; he would stay with a friend of his mother’s who had offered him almost free rent and board. Eventually we would find an apartment and move in together. In the pleasant mist of these daydreams, I didn’t think about how we would pay the rent; his mother had no money, I knew neither of my parents would subsidize my living in sin, and Michael had never shown the slightest desire to find a job. I had left the salad and the shrimp at The Bellows behind; my vast restaurant experience got me hired as a waitress at The Flamette, where despite my dropping a full glass pitcher of maple syrup my first day and my inability to carry more than two plates at a time, I was making enough to buy drugs and squirrel away some spending money for college.

East High had no guidance counselors to talk to about universities; the only adult who had spoken to me about college was my grandmother, who offered to pay my tuition if I went to St. Scholastica, a Catholic woman’s school right there in Duluth. No thank you.

I filled out the application for the University of Minnesota, wrote the essay, tore out and filled in a check for $15 from my mother’s checkbook (she had finally gotten her own bank account), and sent the package off to Minneapolis, never doubting that I would get in and never considering applying to any other schools. The housing catalog that came with my acceptance letter featured a brand new, co-ed dorm, the only dorm that allowed 24-hour visitation from the opposite sex — as long as you had your parents’ permission. I checked the box for Middlebrook Hall on my housing form, forged my mom’s name on the permission slip, and fell into a fantasy of unlimited sex with unlimited college boys, with an occasional guest appearance by Michael Vlasdic.

For once the reality matched the daydream. My perky, adorable, All-American college roommate, Nancy Lowe, went back to her suburban home every weekend to work at the local pizza place and have sex with her own boyfriend, leaving me a wonderfully empty dorm room for entertaining. I was sandwiched between boys; at Middlebrook Hall the sexes alternated floors. My new friend Liz Hepper, who I had met in her dorm room closet, where she was chugging a bottle of Southern Comfort, introduced me to a herd of funny, smart boys from her hometown of Rochester, including a pharmacy major who had very good drugs. There were so many boys in my dorm, and they were all so interesting and cute. And out on the huge campus there were 20,000 more, surrounding me in class, eating dinner in the cafeteria, napping or reading or throwing Frisbees on the still-green campus lawns.

Despite all our plans, despite my absent roommate and the 24-hour visitation, despite how much I thought I looked forward to the first time I could sleep with him, entwined and spooned and inhaling his sweet spicy scent, Michael and I never spent a single night in my skinny dorm bed.

Before the first week of college was out, I called Michael and broke up with him, in the worst way possible, over the phone.

There was another important phone call that first month of my freshman year. My mother called to tell me that she was moving to Colorado Springs. She did not tell me that she was moving in pursuit of the ex-Catholic father of six, who had finally left his wife; he had also left Duluth to live on a small ranch in Colorado. I was instructed to come back home that weekend to box up anything I did not want sold or thrown out; my mother and sisters were downsizing from a six-bedroom stately home to a two-bedroom apartment.

I wandered through 101 Hawthorne, most of the rooms already empty of furniture. Almost everything was gone from my old bedroom, where I had spent so many nights tripping, transfixed by the golden glow from the streetlight streaming through the trees. A few summer clothes hung in my closet; I put them in my suitcase, looking forward to catching some boy’s eye in my cute Indian-print sundress in the spring.

I went back down to the TV room, where our bookshelves were, and where two large cardboard boxes sat gaping. “Put what you want to keep in one,” said my mother. I pulled from the shelves the books that had been my youthful frigates: Alice’s Adventures, the Tennile drawings only slightly defaced from Crayolas wielded by my sister Lani. The Wizard of Oz. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Anderson, minus “The Little Mermaid” and “The Little Match Girl.” I opened up the books Michael had given me, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, each frontispiece signed “I love you” illustrated by his round smiling face. My heart gave a small twist as I stowed them in the moving box. Next came the never-paid-for plays of William Shakespeare, three heavy tomes, The Histories barely cracked. I added The Guide to Minnesota Fauna and Flora, which had been handed to me by the outdoorsy old lesbian who had dragged me around Duluth’s fields and woods. Here was Angelique and the Sultan, with steamy seduction scenes on every page, never returned to Kathy O’Dell. A ragged paperback sci-fi novel, The Blind Spot, that I had read three times in a row, on that trip to Mexico, lacking any other English-language reading material that was not dental-related. And of course the fruit of my junior year with Mr. Burrows, the two volumes of American history and literature, typed out night after night, with my name printed on the spine in gilt letters.

I sealed my cherished books up in a moving box and told my mother that was all I wanted shipped to Colorado. That Christmas break, in my mom’s ticky-tacky Colorado Springs apartment, I sat in the living room, hemmed in by our old furniture: the mahogany dining table for six, the gold and cream French Provincial sofa and matching end tables, and the immense cabinet TV. I opened a cardboard box identified as “Gay’s Books” in black marker. It contained stained Junior League cookbooks, several years of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, a collection of Harold Robbins paperbacks, a single addendum to the World Book, dated 1960, and a battered Webster’s dictionary. My childhood was gone.

The Memory Secret

I was a grind.

That was the word for it back in the day: the kid who sweated the details, who made flashcards. A striver, a grade-hog, a worker bee — that kid — and I can see him clearly now, almost 40 years later, bent over a textbook, squinting in the glow of a cheap desk lamp.

I can see him early in the morning, too, up and studying at 5 o’clock: sophomore year, high school, his stomach on low boil because he can’t quite master — what? The quadratic formula? The terms of the Louisiana Purchase? The Lend-Lease policy, the mean value theorem, Eliot’s use of irony as a metaphor for … some damn thing?

Never mind.

It’s long gone, the entire curriculum. All that remains is the dread. Time’s running out, there’s too much to learn, and some of it is probably beyond reach. But there’s something else in there, too, a lower-frequency signal that takes a while to pick up, like a dripping faucet in a downstairs bathroom: doubt. The nagging sense of having strayed off the trail when the gifted students were arriving at the lodge without breaking a sweat. Like so many others, I grew up believing that learning was all self-discipline: a hard, lonely climb up the sheer rock face of knowledge to where the smart people lived. I was driven more by a fear of falling than by anything like curiosity or wonder.

That fear made for an odd species of student. To my siblings, I was Mr. Perfect, the serious older brother who got mostly As. To my classmates, I was the Invisible Man, too unsure of my grasp of the material to speak up. I don’t blame my young self, my parents, or my teachers for this split personality. How could I? The only strategy any of us knew for deepening learning — drive yourself like a sled dog — works, to some extent; effort is the single most important factor in academic success.

Yet that was the strategy I was already using. I needed something more, something different — and I felt it had to exist.

The first hint that it did, for me, came in the form of other students, those two or three kids in algebra or history who had — what was it? — a cool head, an ability to do their best without that hunted-animal look. It was as if they’d been told it was okay not to understand everything right away; that it would come in time; that their doubt was itself a valuable instrument. But the real conversion experience for me came later, when applying for college. College was the mission all along, of course. And it failed; I failed. I sent out a dozen applications and got shut down. All those years laboring before the mast and, in the end, I had nothing to show for it but a handful of thin envelopes.

What went wrong?

I had no idea. I aimed too high, I wasn’t perfect enough, I choked on the SATs. No matter. I was too busy feeling rejected to think about it. No, worse than rejected. I felt like a chump. Like I’d been scammed by some bogus self-improvement cult, paid dues to a guru who split with the money. So, after dropping out, I made an attitude adjustment. I loosened my grip. I stopped sprinting. Broadened the margins, to paraphrase Thoreau. It wasn’t so much a grand strategy — I was a teenager, I couldn’t see more than three feet in front of my face — as a simple instinct to pick my head up and look around.

I finally got into the University of Colorado, where I began to live more for the day. Hiked a lot, skied a little, consumed too much of everything. I’m not saying that I majored in gin and tonics; I never let go of my studies — just allowed them to become part of my life, rather than its central purpose. And somewhere in that tangle of good living and bad, I became a student.

The change wasn’t sudden or dramatic. No bells rang out, no angels sang. It happened by degrees, like these things do. For years afterward, I thought about college like I suspect many people do: I’d performed pretty well despite my scattered existence, my bad habits. I never stopped to ask whether those habits were, in fact, bad.

In the early 2000s, I began to follow the science of learning and memory as a reporter, first for the Los Angeles Times and then for The New York Times. This subject — specifically, how the brain learns most efficiently — was not central to my beat. But I kept coming back to it, because the story was such an improbable one. Here were legit scientists, investigating the effect of apparently trivial things on learning and memory. Background music. Study location, i.e., where you hit the books. Video game breaks. Honestly, did those things matter at test time, when it came time to perform?

If so, why?

After experimenting with many of the techniques described in the studies, I began to feel a creeping familiarity, and it didn’t take long to identify its source: college. My jumbled, ad hoc approach to learning in Colorado did not precisely embody the latest principles of cognitive science — nothing in the real world is that clean. The rhythm felt similar, though, in the way the studies and techniques seeped into my daily life, into conversation, idle thoughts, even dreams.

That connection was personal, and it got me thinking about the science of learning as a whole, rather than as a list of self-help ideas. The ideas — the techniques — are each sound on their own, that much was clear. The harder part was putting them together. They must fit together somehow, and in time I saw that the only way they could was as oddball features of the underlying system itself — the living brain in action. To say it another way, the collective findings of modern learning science provide much more than a recipe for how to learn more efficiently. They describe a way of life.

The brain is not like a muscle. It is something else altogether, sensitive to mood, to timing, to circadian rhythms, as well as to location, environment. It registers far more than we’re conscious of and often adds previously unnoticed details when revisiting a memory or learned fact. It works hard at night, during sleep, searching for hidden links and deeper significance in the day’s events. It has a strong preference for meaning over randomness, and finds nonsense offensive. It doesn’t take orders so well, either, as we all know — forgetting precious facts needed for an exam while somehow remembering entire scenes from The Godfather or the lineup of the 1986 Boston Red Sox.

In the past few decades, researchers have uncovered and road-tested a host of techniques that deepen learning — techniques that remain largely unknown outside scientific circles. These approaches aren’t get-smarter schemes that require computer software, gadgets, or medication. Nor are they based on any grand teaching philosophy, intended to lift the performance of entire classrooms (which no one has done, reliably). On the contrary, they are all small alterations, alterations in how we study or practice that we can apply individually, in our own lives, right now.

In short, it is not that there is a right way and wrong way to learn. It’s that there are different strategies, each uniquely suited to capturing a particular type of information.

The Ways We Learn: Separating Myth from Fact in the Quest for Better Retention

Some of what I’ve learned about how we learn can be found in the answers to a few essential questions.

Can “freeing the inner slacker” really be called a legitimate learning strategy?

If it means guzzling wine in front of the TV, then no. But to the extent that it means appreciating learning as a restless, piecemeal, subconscious, and somewhat sneaky process that occurs all the time — not just when you’re sitting at a desk, face pressed into a book — then it’s the best strategy there is.

How important is routine when it comes to learning?

Not at all. Most people do better over time by varying their study or practice locations. The more environments in which you rehearse, the sharper and more lasting the memory of that material becomes — and less strongly linked to one “comfort zone.” Altering the time of day you study also helps, as does changing how you engage the material, by reading or discussing, typing into a computer or writing by hand, reciting in front of a mirror or studying while listening to music: Each counts as a different learning “environment” in which you store the material in a different way.

How does sleep affect learning?

Studies show that “deep sleep,” which is concentrated in the first half of the night, is most valuable for retaining hard facts — names, dates, formulas, concepts. If you’re preparing for a test that’s heavy on retention (foreign vocabulary, names and dates, chemical structures), it’s better to hit the sack at your usual time, get that full dose of deep sleep, and roll out of bed early for a quick review. But the stages of sleep that help consolidate motor skills and creative thinking — whether in math, science, or writing — occur in the morning hours, before waking. If it’s a music recital or athletic competition you’re preparing for, or a test that demands creative thinking, you might consider staying up a little later than usual and sleeping in.

Is there an optimal amount of time to study or practice?

More important than how long you study is how you distribute the study time you have. Breaking up study or practice time — dividing it into two or three sessions, instead of one — is far more effective than concentrating it. That split forces you to reengage the material, dig up what you already know, and restore it — an active mental step that reliably improves memory.

How much does it help to review notes from a class or lesson?

The answer depends on how the reviewing is done. Verbatim copying adds very little to the depth of your learning, and the same goes for looking over highlighted text or formulas. Just because you’ve marked something or rewritten it, digitally or on paper, doesn’t mean your brain has engaged the material more deeply. Studying highlighted notes and trying to write them out — without looking — works memory harder and is a much more effective approach to review. There’s an added benefit as well: It also shows you immediately what you don’t know and need to circle back and review.

Is distraction always bad?

No. Distraction is a hazard if you need continuous focus, like when listening to a lecture. But a short study break — five, 10, 20 minutes to check in on Facebook, respond to a few emails, check sports scores — is the most effective technique learning scientists know of to help you solve a problem when you’re stuck. Distracting yourself from the task at hand allows you to let go of mistaken assumptions, reexamine the clues in a new way, and come back fresh.

Is it best to practice one skill at a time or many things at once?

Focusing on one skill at a time — a musical scale, free throws, the quadratic formula — leads quickly to noticeable, tangible improvement. But over time, such focused practice actually limits our development of each skill. Mixing or “interleaving” multiple skills in a practice session, by contrast, sharpens our grasp of all of them.

—

From the book How We Learn by Benedict Carey. Copyright © 2014 by Benedict Barey. Published by arrangement with Random House, a division of Random House LLC.

Before I Go

In residency, there’s a saying: The days are long, but the years are short. In neurosurgical training, the day usually began a little before 6 a.m., and lasted until the operating was done, which depended, in part, on how quick you were in the operating room.

A resident’s surgical skill is judged by his technique and his speed. You can’t be sloppy and you can’t be slow. From your first wound closure onward, spend too much time being precise and the scrub tech will announce, “Looks like we’ve got a plastic surgeon on our hands!” Or say: “I get your strategy — by the time you finish sewing the top half of the wound, the bottom will have healed on its own. Half the work — smart!” A chief resident will advise a junior: “Learn to be fast now — you can learn to be good later.” Everyone’s eyes are always on the clock. For the patient’s sake: How long has the patient been under anesthesia? During long procedures, nerves can get damaged, muscles can break down, even causing kidney failure. For everyone else’s sake: What time are we getting out of here tonight?

There are two strategies to cutting the time short, like the tortoise and the hare. The hare moves as fast as possible, hands a blur, instruments clattering, falling to the floor; the skin slips open like a curtain, the skull flap is on the tray before the bone dust settles. But the opening might need to be expanded a centimeter here or there because it’s not optimally placed. The tortoise proceeds deliberately, with no wasted movements, measuring twice, cutting once. No step of the operation needs revisiting; everything proceeds in orderly fashion. If the hare makes too many minor missteps and has to keep adjusting, the tortoise wins. If the tortoise spends too much time planning each step, the hare wins.

The funny thing about time in the OR, whether you frenetically race or steadily proceed, is that you have no sense of it passing. If boredom is, as Heidegger argued, the awareness of time passing, this is the opposite: The intense focus makes the arms of the clock seem arbitrarily placed. Two hours can feel like a minute. Once the final stitch is placed and the wound is dressed, normal time suddenly restarts. You can almost hear an audible whoosh. Then you start wondering: How long till the patient wakes up? How long till the next case gets started? How many patients do I need to see before then? What time will I get home tonight?

It’s not until the last case finishes that you feel the length of the day, the drag in your step. Those last few administrative tasks before leaving the hospital, however far post-meridian you stood, felt like anvils. Could they wait till tomorrow? No. A sigh, and Earth continued to rotate back toward the sun.

But the years did, as promised, fly by. Six years passed in a flash, but then, heading into chief residency, I developed a classic constellation of symptoms — weight loss, fevers, night sweats, unremitting back pain, cough — indicating a diagnosis quickly confirmed: metastatic lung cancer. The gears of time ground down. While able to limp through the end of residency on treatment, I relapsed, underwent chemo, and endured a prolonged hospitalization.

I emerged from the hospital weakened, with thin limbs and thinned hair. Now unable to work, I was left at home to convalesce. Getting up from a chair or lifting a glass of water took concentration and effort. If time dilates when one moves at high speeds, does it contract when one moves barely at all? It must: The day shortened considerably. A full day’s activity might be a medical appointment, or a visit from a friend. The rest of the time was rest.

With little to distinguish one day from the next, time began to feel static. In English, we use the word time in different ways, “the time is 2:45” versus “I’m going through a tough time.” Time began to feel less like the ticking clock, and more like the state of being. Languor settled in. Focused in the OR, the position of the clock’s hands might seem arbitrary, but never meaningless. Now the time of day meant nothing, the day of the week scarcely more so.

Verb conjugation became muddled. Which was correct? “I am a neurosurgeon,” “I was a neurosurgeon,” “I had been a neurosurgeon before and will be again”? Graham Greene felt life was lived in the first 20 years and the remainder was just reflection. What tense was I living in? Had I proceeded, like a burned-out Greene character, beyond the present tense and into the past perfect? The future tense seemed vacant and, on others’ lips, jarring. I recently celebrated my 15th college reunion; it seemed rude to respond to parting promises from old friends, “We’ll see you at the 25th!” with “Probably not!”

Yet there is dynamism in our house. Our daughter was born days after I was released from the hospital. Week to week, she blossoms: a first grasp, a first smile, a first laugh. Her pediatrician regularly records her growth on charts, tick marks of her progress over time. A brightening newness surrounds her. As she sits in my lap smiling, enthralled by my tuneless singing, an incandescence lights the room.

Time for me is double-edged: Every day brings me further from the low of my last cancer relapse, but every day also brings me closer to the next cancer recurrence — and eventually, death. Perhaps later than I think, but certainly sooner than I desire. There are, I imagine, two responses to that realization. The most obvious might be an impulse to frantic activity: to “live life to its fullest,” to travel, to dine, to achieve a host of neglected ambitions. Part of the cruelty of cancer, though, is not only that it limits your time, it also limits your energy, vastly reducing the amount you can squeeze into a day. It is a tired hare who now races. But even if I had the energy, I prefer a more tortoise-like approach. I plod, I ponder, some days I simply persist.

Everyone succumbs to finitude. I suspect I am not the only one who reaches this pluperfect state. Most ambitions are either achieved or abandoned; either way, they belong to the past. The future, instead of the ladder toward the goals of life, flattens out into a perpetual present. Money, status, all the vanities the preacher of Ecclesiastes described, hold so little interest: a chasing after wind, indeed.

Yet one thing cannot be robbed of her futurity: my daughter, Cady. I hope I’ll live long enough that she has some memory of me. Words have a longevity I do not. I had thought I could leave her a series of letters — but what would they really say? I don’t know what this girl will be like when she is 15; I don’t even know if she’ll take to the nickname we’ve given her. There is perhaps only one thing to say to this infant, who is all future, overlapping briefly with me, whose life, barring the improbable, is all but past.

That message is simple: When you come to one of the many moments in life when you must give an account of yourself, provide a ledger of what you have been, and done, and meant to the world, do not, I pray, discount that you filled a dying man’s days with a sated joy, a joy unknown to me in all my prior years, a joy that does not hunger for more and more, but rests, satisfied. In this time, right now, that is an enormous thing.

Republished with permission from Stanford Medicine magazine (stanmed.stanford.edu/2015spring/before-i-go.html).

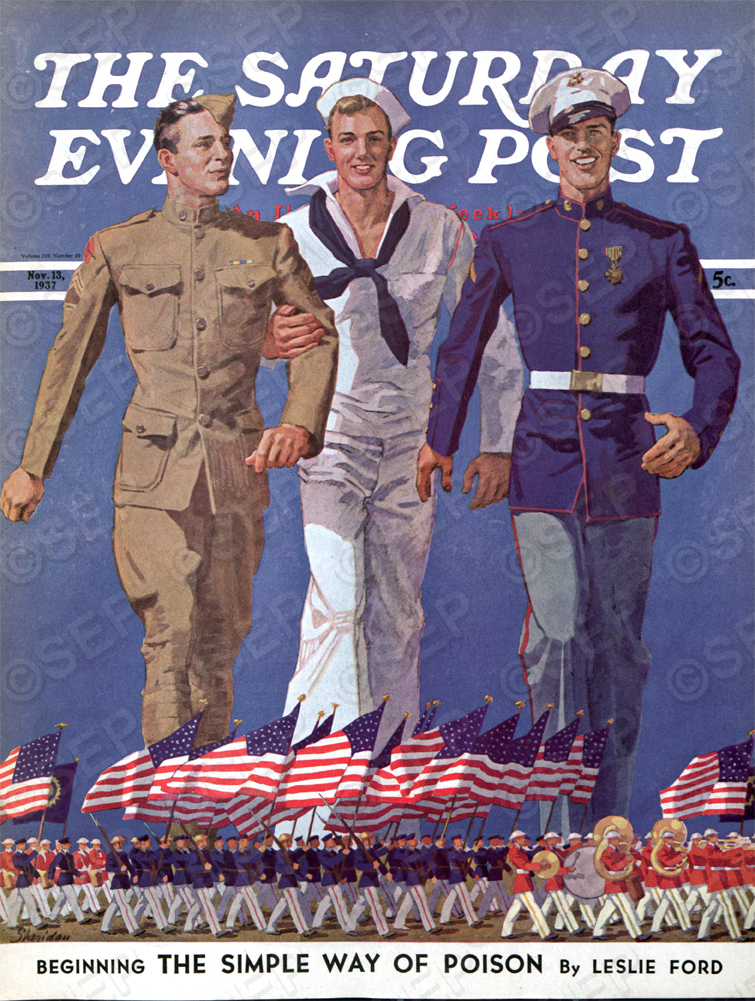

Tribute to Our Troops Essay Contest Winners

Thank you to all who participated in The Saturday Evening Post’s Tribute to Our Troops essay contest.

“The Saturday Evening Post, for nearly 300 years, has been proud to showcase the American way, and through this contest we honor soldiers past and present who risk their lives every day for our country,” says Steven Slon, editorial director and associate publisher. “We are very excited to present the inspiring tributes from our readers.”

Each of the winners will receive a watch courtesy of our co-sponsor Speidel.

“Speidel is very proud to have been a part of The Saturday Evening Post Tribute to Our Troops essay contest, and we offer our heartfelt thanks and congratulations to each of the winners,” said Lynn-Marie Cerce, co-owner of Speidel. “We would also like to thank all of our loyal customers—many of them Saturday Evening Post readers—who help us provide critically-needed financial support and services to members of the military and their families through our Change A Band, Change A Life™ charitable giving program.”

As part of the program Speidel is donating a portion of all sales proceeds, including purchases made online at speidel.com to Operation Homefront.

The following essays are the top 20 entries selected by the Post editors:

Honor Thy Brother

By Elizabeth Heaney

Walking through the battalion offices, I see a big, broad-shouldered staff sergeant intently focused on a dark blue uniform lying on his desktop. As I watch from the doorway, he leans over and places a narrow silver pin on the uniform’s chest. Before attaching the pin, he checks its placement in all four directions with a measuring device that calculates tiny, perfect millimeters.

After securing the pin, he checks each brass button down the front of the uniform in those same precise millimeters.

He’s wearing delicately thin white gloves on his huge hands, and touches the uniform gently, reverently. I’d seen soldiers prepare their dress uniforms to go up for promotion; this was different.

“Looks nice—you up for promotion?” I say from the doorway.

“No, ma’am. I’m escorting Tompkins’ body back to Iowa.”

Silence stretches between us.

“I’m so sorry you have to do that.” Then I add, “And I’m very grateful you will.”

“I wouldn’t have it any other way, ma’am. He was my soldier.”

Always a Hero

By Anne Linja

Navy Master Chief David Charles Linja—my husband, my hero—was holding my hand as we headed towards his retirement ceremony. There were many emotions and thoughts going through my mind. The most prevalent was “He’s coming home to us, our family. The U.S. may have had his heart, soul, and body for 30 years—and thankfully he stayed safe throughout all those years—but now he’ll be husband, dad, brother, son.”

As we stepped into the elevator, a fellow squid said, “Good morning, Master Chief!”

I responded, “He’s retiring today. It’s his last day.”

The sailor looked at me and respectfully said, “No, ma’am. He’ll always be a master chief.”

My husband suddenly had the biggest grin on his face, full of pride, knowing that he spent the last 30 years doing exactly what he was supposed to do.

Job Well Done

By Kathy Manier

While growing up in Orange County, I was always taught to thank our military for their service but never really had a full grasp of why I was thanking them—except for the obvious reason, fighting for my freedom.

Within the last couple years, I’ve personally come to know many service members, and their stories are humbling to say the least. To them, they are not heroes nor see any need to be thanked. They go to work every day like the rest of us—to do their job as best as they know how—except they don’t always get to come home at the end of the day.

They leave their families for months on end, work through holidays, and take the weight of the world’s problems on their shoulders. They sacrifice their safety, getting shot at, but for them it’s just another day at the office.

So for all the tears before each deployment, the PTSD that becomes the norm, the loved ones that are lost, the weeks of training in the middle of nowhere with no shower or bed, and the endless sacrifices they make on a daily basis, I thank them for their service, for just doing what they consider their “job.”

In the Steps of Our Ancestors

By Debbi Nelson

As a female child born into a lineage of proud males, I was raised on stories of ancestors who fought and died in the great conflicts—dating back to the American Revolution—of these United States. Images of draft cards and photos and the family stories still hold places of honor in my mind. As a youth, I could recite the stories, but, as an adult, I can feel them.

These were gutsy, in-your-face characters that hid their fears and left their families to benefit something bigger than themselves. Some never returned to their mothers or children. Some carried the horrors of war with them for the rest of their lives. But all of them watched with real pride each time the wind was slapped back by the Stars and Stripes. Their lives, and the lives of their comrades, were gifts that will never be forgotten.

Today, in big cities and small towns across this country, the tradition continues. I see young men and women putting their lives on hold in order to put on uniforms. The transportation and technology are different, but the American soldier is still the same, unafraid to defend. May God bless their every step!

No Thank You Required

By Greg Woodburn

After enjoying a wonderful meal on vacation with our two then-young children, we waited for our check.

Ten minutes became 30.

And we finally left without paying, but let me explain: Two businessmen across the room paid our bill, but requested we not be told until after they left. They saw a happy family, the waiter now explained, and simply wanted to do something kind with no thank you required.

Fourteen years passed, and then, last summer when I was leaving a local steak house, a U.S. soldier dressed in camouflage walked in.

“Hi,” I said. ”I want to thank you for all you do.”

“I appreciate that very much, sir,” the authentic American hero humbly replied while shaking my hand.

I wanted to say more, something less trite, but the table for two was ready and the hostess led the strapping soldier and his happy mother away.

I hope they ordered appetizers, wine to celebrate his homecoming, prime rib, plus dessert. And afterwards, I hope they had to wait a good long while, enjoying each other’s company and some laughs—even as they grew a bit impatient wondering where in the world their waiter was with the check.

Understanding Adult ADHD

Brook Ochoa, 42, doesn’t fidget or squirm or bounce off walls like an 8-year-old child with ADHD. That’s primarily because she’s an adult, and adults tend to lack the hyperactivity part. The single mother of two has plenty of other symptoms, however. “I read seven books at a time, have never finished a project in my life, and when I get bored with a job I just walk away. I never knew until recently that that wasn’t normal. If it’s boring, I’m done.”

“Boring” is the kiss of death to adults with ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or just ADD if they lack the hyperactivity component). And her inability to stay interested in any one subject for long may explain why Brook quit several jobs as manager and assistant manager of stores like Target and Wal-Mart. Brook is certainly competent enough to handle a heavy workload. She did well in school and earned a master’s degree in human resources; she can focus and finish assignments when they interest her. But around the house, she struggles with such simple tasks as washing dishes after meals. “Every dish in the house has to be dirty before I notice,” says Brook with a sigh. (See also “Symptoms of ADHD.”)

But at least she knows where her demons lie. For adults who were not diagnosed as children—and anyone who was already an adult when ADHD became widely recognized in children in the 1990s is unlikely to have been—having a label affixed to their struggles allows them to finally seek help. Perhaps even more important, it lets them make sense of a lifetime of bewildering experiences, of feeling hopeless or helpless in the face of their mental dysfunction, and, in many cases, wondering why they never achieved what they felt they could have.

“The more she described ADD the more the light bulb lit up for me,” recalls Robin Bellantone, 61, a mental health counselor in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. She had no idea adult ADD existed when she had the life-altering conversation during her graduate-school internship at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 1999. It was there that she heard a fellow staffer who specialized in working with artists with ADHD talking about the disorder: “It explained so much about my own history”—her inability to focus, her difficulty paying attention, her constant search for new stimulation.

Stories of adults who finally learn they have ADHD are as unique as the people themselves, but they have at least one thing in common: a sense that what was once shrouded in mystery is now lit with understanding, that a weight has been lifted and a puzzle solved. The National Institute of Mental Health estimates that 4.1 percent of adults have ADHD in any given 12-month period (compared to 9 percent of children). In the young, three times as many boys as girls have ADHD, but by adulthood the prevalence is the same in both sexes.

For adults, having the ADHD label affixed to their struggles allows them to finally seek help.

If it sometimes seems that everyone has some form of ADHD in today’s disjointed world of smartphones, tablets, and the like, the formal diagnosis is indeed on the verge of becoming more common. The newest edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, scheduled for release in May 2013, is expected to loosen the diagnostic criteria for the disorder substantially, lowering the number of symptoms required. (See chart, “Symptoms of ADHD,” next page.) But, even so, there are misconceptions about what it takes to qualify. For example, inability to focus and being easily distracted—with no other symptoms—wouldn’t be enough. You do not have ADHD if you simply like to flit from task to task at work. You do not have ADHD if you get bored doing housework. You do not have it if your mind wanders when reading dense, boring prose on a topic you have no interest in; if you get fidgety during boring sermons or hours-long presentations from a financial planner; or if you start reading another book or magazine before you finish the previous one you’ve started.

Moreover, the symptoms must appear in at least two settings: If you only show these behaviors at work, then you do not have ADHD. You probably just don’t like your job.

Still, the condition is underdiagnosed. Today, for every adult whose ADHD has been identified, there are at least three adults whose ADHD has not, according to Dr. Mary Solanto of Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. Underdiagnosis reflects that adults can compensate for ADHD by choosing jobs that fit their brains—for instance jobs that present constant new challenges rather than jobs where one does the same task over and over.

That probably explains why Ruth didn’t receive her diagnosis until age 74. As a young woman she had few friends, felt isolated, and often blurted out what she felt without much thought for the consequences. Then, after marrying and raising a family, Ruth—who did not want her full name used—went to nursing school at age 46. She adored her new career. “I was busy all of the time. It’s never boring,” she says.

Tips to Help You Fly Through Airport Security

No time exists on your calendar for lingering in a long airport security line, but if you’re traveling by plane, you can’t avoid security checkpoints. While you’ll be trapped in the line for at least a bit, embrace a few tricks used by veteran travelers to mitigate the waiting.

1. Get to the airport before the sun comes up

Security lines tend to be shorter earlier in the morning. If you can manage to get a very early flight, you’ll find that slipping through security lines is a much quicker process. Just as important, leave yourself plenty of time to get through the lines. If you’re in a rush trying not to miss your flight, your blood pressure will shoot up and your trip could be miserable.

2. Check your luggage at the door

Yes, checking luggage can be a pain in the neck. It takes a little time, it might cost some money, and your unmentionables could find themselves flown to parts unknown. But hauling your luggage through security means that your security check could take longer. If something in your luggage requires inspection, then your time in line just tripled. Don’t rely on odd luggage gimmicks to get you past carry-on restrictions. Just check the bag. Another huge benefit to checking your bags is that you’re not forced to haul all your luggage throughout the airport. It’s just more convenient.

3.Keep carry-on size reasonable

Travelers are constantly trying to sneak larger and larger carry-on bags onto the plane. Don’t do that. Use your carry-on bags only for electronics, medicine, and maybe a change of clothes — you know, the stuff you absolutely need. If you don’t have large carry-ons you’ll need to stuff into an overhead bin in the plane, the chance those bins might be too full isn’t your problem.

4. Open your bags all the way

While checkpoint-friendly bags can make your time in line a little easier, security officers will still occasionally need to get into your bags. Don’t make them unzip, unlatch, or untie the fasteners on your bag. It uses up a bit of time, of course, but it also means the officer needs to manhandle your bags. If you’re worried about popping a zipper, open your bag all the way before the officers have to. After all, if you do happen to get pulled aside for a closer inspection, you won’t be allowed to touch your bags further. Get your bags open all the way before you put them on the conveyor belt.

5. Pack cables separately and unattached

Music players have headphones, and laptops have power cords. Wrap up individual wires separately from one another, and keep the whole bunch as neat as possible. Stow these cables and wires in a separate bag or pocket if you can. This reduces the tangle of wires you’ll have to sort through in line and makes it easier for the security officers to see them on an X-ray screen.

6. Pay attention to the lines, not your music

We couldn’t tell you the number of times we’ve seen TSA officers try to provide instructions, only for their intended recipients to be too busy with a smartphone, MP3 player, or portable video game to actually pay attention. Don’t do that. It makes the process longer for yourself, and it’s frustrating for everyone around you.

7. Don’t wear a belt; do wear slip-on shoes

When you go through the security checkpoint, the officers scan for metal items on your person that hypothetically could be a threat to the flight. That huge archway you walk through is essentially a giant metal detector. That’s why you have to take off your shoes and usually your belt; those accessories tend to have misleading metal included. Your trip through the metal detector will be a little lower on the stress if you can just pop your shoes off without wrestling with laces.

8. Don’t try to bring any prohibited items

While some of the items you can’t carry on a plane are just common sense (knives and weapons, for example, aren’t allowed), some aren’t. Save yourself time by familiarizing yourself with the TSA’s guidelines for prohibited items in advance.

The key to saving time in the security line at the airport is to avoid anything that could turn into a hassle. Extra luggage can be a big deal, so check any bags you don’t absolutely need to keep with you. Keeping your carry-on light and opening it all the way in line will save you some trouble. If you’re not wearing a belt, you won’t have to bother taking it off. Lastly, keep everything organized in your bags. The faster you can open everything up in line, the better off you’ll be.

This story originally appeared on Tecca.

More from Tecca:

Travel Tech Guide: How to travel well with technology