For the Love of Streetcars

Peter Kocan—with editor Ashley Halsey, Jr.—describes a purist’s love for the streetcar.

Peter Kocan—with editor Ashley Halsey, Jr.—describes a purist’s love for the streetcar.

Kocan, enthralled with the streetcar, took a 14,300-mile journey on 92 systems throughout the United States. The following excerpt is a bit of this extraordinary journey from a 1947 article in the Post. Three of the cities mentioned in this excerpt still have working streetcars today.

[See also: “The Looming Crisis in Mass Transit” from our Jul/Aug 2012 issue.]

Some of My Best Friends Are Streetcars

December 6, 1947—I began on April Fool’s Day of 1946 after getting out of the Army, which had isolated me on a streetcar-less corner of the island of Ceylon in the Indian Ocean. After landing in San Francisco, I went east to my home in New York and then started out on a transcontinental junket that took me south; west and east again through forty-five cities.

There are only 10 systems in the country that I haven’t ridden, and three of those are small interurbans. My mileage on the tour would have been even higher except for that strike in Los Angeles, which began two days before I arrived there. As the strike kept on, my funds ran low. I finally gave up, but not before setting what may be a world’s record. For eleven days I waited in vain for a streetcar.

Before leaving Southern California, I rode perhaps the chummiest streetcar line in the world-one that very nearly yanks its passengers aboard by the coat collar and helps them to seats. This is the Santa Monica Airline, which treats every straphanger like a stockholder. Despite its high-flown name, the Airline spends much of its time rambling through industrial back yards and darting cautiously across intersections to the shelter of the next alley.

The line is strictly a silent partner in the Pacific Electric Railway, described as the largest interurban system on earth. It does not appear on timetables, is never advertised, and makes only one round trip a day, to hold its franchise.

The same motorman, “Brownie,” has operated its entire rolling stock for years. He believes in giving individual service. While I was on his car, we halted at a corner. Minutes passed. Nobody got on or off.

“Why have we stopped?” somebody asked.

“Mr. Robinson usually gets on here,” Brownie explained. Sure enough, in a couple of minutes Mr. Robinson came tearing around the corner. One regular woman passenger failed to show up at all, however, and Brownie got worried. “Maybe she’s sick,” he fretted. “I certainly hope not. She’s a fine woman.”

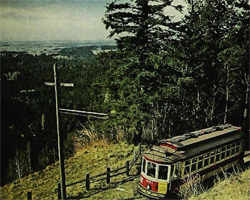

Another traction wonder of the West Coast is a trolley route at Portland, Oregon, which spins the traveler through nearly ten complete circles in two and a third miles. There are sixty-seven merry-go-round curves, or an average of one every 180 feet. The trolley shoots up 1038 feet of mountainside to Council Crest Park along grades sometimes as steep as 12 per cent. To check the cars on their dizzy downward trip, the Portland Traction Company has thoughtfully installed ten derailing switches. Each automatically halts cars for nine seconds.

For truly fancy performances in the field of transit, no place on earth can beat Fort Collins, Colorado, smallest town in the United States to boast a trolley system. The town, population 12,250, owns five streetcars and holds two of them in reserve, It operates three at a time on its three single tracked lines: a large loop through the main section of town, a small loop on the other side of town, and a long connecting line.

If each streetcar stuck to its own back yard, the Fort Collins traction system would be as humdrum as any stay-at-home. To give the longest possible ride for the money, however, the city fathers decreed that two cars should serve both loops via the connecting line while the third circles the large loop. Since these complex gyrations are performed on a single-track system, they might be expected to constitute a triple threat to the future of the streetcar.

Fort Collins solves all its safety, switching and passenger-transfer problems, however, with one ingenious small-town stunt. Every twenty minutes all three trolleys in use confront one another in the town square just a few feet short of a collision. Anyone that arrives ahead of schedule has to wait. At the proper moment, the three motormen exchange greetings and drive ahead. Just as a triple collision of catastrophic proportions seems inevitable, the cars swerve and narrowly pass one another on a wye track in the town square. Big-city folks may compare this comedy act with Toonerville Trolley antics, but the municipally owned Fort Collins system holds two impressive distinctions. It has the lowest trolley fares in the country—five cents a ride, six tokens for a quarter or one dollar for an unlimited monthly pass—and it operates at a profit.