Considering History: The Washington Redskins, Oklahoma Territory, and the Myth of the “Vanishing Indian”

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

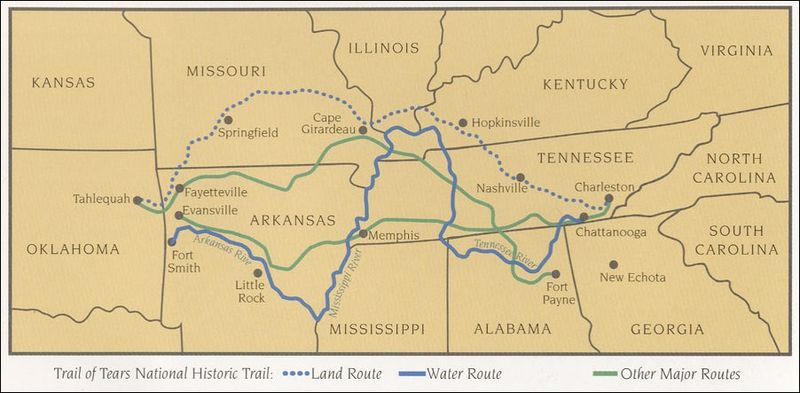

Recently, we have seen two striking decisions on longstanding issues connected to Native American communities. On July 9, in one of its last announced decisions of this session, the Supreme Court ruled that the eastern half of the state of Oklahoma remains “Indian territory” under 19th century treaties that guaranteed the land for tribes forced west on the Trail of Tears, treaties that have never been amended by Congress and so (the Court ruled) continue to hold today. And on July 13, the NFL franchise the Washington Redskins formally announced that the team will be changing its nearly century-old racist name and logo.

The details of these two decisions are quite specific to their respective arenas, and reflect evolving conversations in each case. But taken together, they exemplify two longstanding and contrasting national narratives: those which depict Native Americans through reductive, stereotypical images in order to justify attempts to expel and destroy native communities; and those which recognize instead Native Americans’ foundational and continued presence within America.

In order to justify his proposed, genocidal Indian Removal policy which produced the Trail of Tears, President Andrew Jackson depicted Native Americans through such stereotypical and racist imagery, defining them as savages unable to coexist with European-American communities or indeed exist at all within the expanding Early Republic United States. In his December 1829 first President’s Annual Message to Congress, Jackson argued that “this fate [disappearance] surely awaits them if they remain within the limits of the States.” And in his December 1833 fifth annual message, Jackson went much further, claiming, “That those tribes cannot exist surrounded by our settlements and in continual contact with our citizens is certain…Established in the midst of another and a superior race, and without appreciating the causes of their inferiority or seeking to control them, they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.”

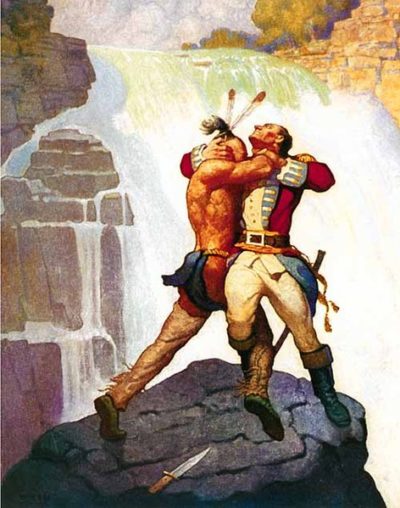

Jackson’s more aggressively racist depictions of Native Americans were complemented by a gentler and more insidious exclusionary perspective that came to be known as the “Vanishing Indian” narrative. Often advanced by figures and communities sympathetic to native rights, this narrative relied on images like the admirable but doomed “Noble Savage” to depict Native Americans as tragically but inevitably disappearing from the continent. James Fenimore Cooper’s bestselling historical novel The Last of the Mohicans (1826) illustrates this trope, arguing from its title on that its heroic Native-American characters are the “last” of a tribe that in fact still existed in Cooper’s era (and still does in our own). Poet Lydia Huntley Sigourney’s “Indian Names” (1834) is even more striking, as Sigourney uses the persistence of Native-American names on the American landscape to angrily (and inaccurately) lament the destruction of native communities: “Ye say they all have passed away,/That noble race and brave/… But their name is on your waters,/Ye may not wash it out.”

The “Vanishing Indian” narrative became a dominant trope across the 19th century and into the 20th, and in subtle but significant ways informed numerous prominent cultural works, as illustrated by Wellesley Professor Katharine Lee Bates’s 1893 poem “America” that became the lyrics for the song “America the Beautiful” (1910). That trope is most apparent in Bates’s second verse, where she describes America’s origin point: “O beautiful for pilgrim feet/Whose stern, impassioned stress/A thoroughfare for freedom beat/Across the wilderness!” But Bates likewise disappears Native Americans from the idealized images of the national landscape with which her poem opens, and which were inspired by a cross-country train trip from her Massachusetts home to a summer teaching job in Colorado. Bates originally named her poem “Pike’s Peak,” as she wrote it after a day trip ascending the mountain — but, like that name itself, her poem leaves no place for the Ute and Arapaho tribes who had been part of that landscape long before explorer Zebulon Pike arrived.

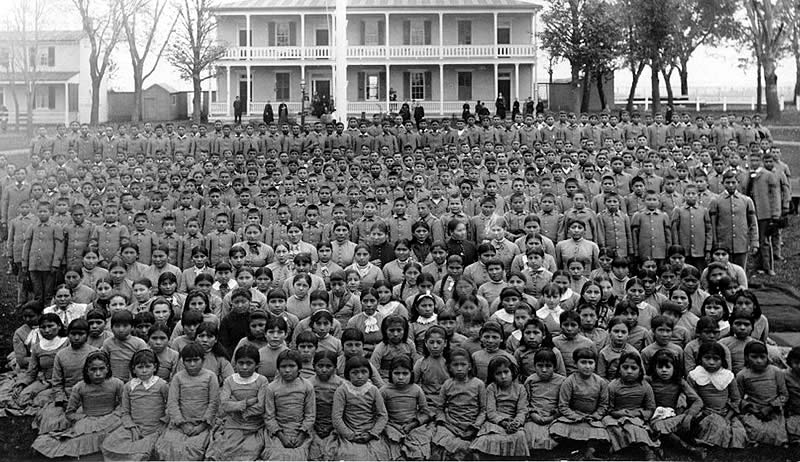

Bates’s 1893 trip took place just two-and-a-half years after the December 1890 Wounded Knee massacre in South Dakota, an exemplification of the far more violent exclusionary attacks upon Native-American communities that continued throughout the 19th century. The late 19th and early 20th century also featured another, even more insidious form of cultural genocide designed to facilitate the disappearance of Native-American cultures: the boarding school movement, which (as Carlisle Indian Industrial School founder and former “Indian Wars” Captain Richard Pratt put it) was intended to “kill the Indian, and save the man.” Both these military and educational efforts illustrate that the “Vanishing Indian” was not just a cultural image, but also and most importantly an ongoing white supremacist goal.

As I wrote in this October 2018 Considering History column, Native-American activists and communities have consistently used legal and political means to challenge such attacks and advocate for their survival and their rights. In response to Jackson’s Indian Removal policy the Cherokee nation did so forcefully, with the tribe’s leaders drafting a series of “Cherokee Memorials” to the U.S. Congress that were published in the tribe’s newspaper The Cherokee Phoenix and submitted to Congress to request their assistance. The Cherokee also took their claims to the court system, and the Supreme Court sided with their rights to their land in the Worcester v. Georgia (1832) decision. Jackson famously ignored the Court and proceeded with removal.

Native-American legal and political efforts continued for the next century-and-a-half, including the two prominent moments I highlighted in my earlier column: Ponca Chief Standing Bear’s legal challenge which resulted in the groundbreaking 1879 decision that “an Indian is a person” for purposes of the law (and otherwise); and the numerous activists, including Zitkala-Ša and Nipo Strongheart, whose advocacy led to the watershed 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

The 1960s and 1970s American Indian Movement, founded in Minneapolis in 1968, continued to utilize the political and legal system to advocate for native lives and rights, while fostering the Red Power and Native-American Renaissance cultural movements of late 20th century America.

These destructive myths and their effects have endured, as illustrated by the horrifically high numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths on Native-American reservations — one more way (among too many, including the kidnappings and murders of native women and the destruction of native lands for pipeline construction) in which native communities continue to face the threat of disappearance. But the Supreme Court decision embodies a perspective in which Native-American rights and presence are seen and supported, and where native communities are defined as foundational and integral parts of America’s history, identity, and future.

Featured image: The delegation of Sioux chiefs to ratify the sale of lands in South Dakota to the U.S. government, December1889 / photo by C.M. Bell, Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress)