Rockwell Files: Commuters

Norman Rockwell’s 1946 cover Commuters was a tribute to fellow artist and friend Anna “Grandma” Moses, who painted in a folk-art style, rarely using perspective to convey distance. Hence, her landscapes appeared flattened and tilted forward so everything in the panorama could be seen. Commuters uses a similar style to portray Tuckahoe, New York, a very flat town that rises here like an Alpine village in the background. But the improbable landscape allowed Rockwell to make all the houses and cars of the neighborhood visible.

Grandma Moses, who only took up painting in her 70s, said she wanted her works to capture “how we used to live.” Similarly, Rockwell’s cover evokes a morning rush hour from 74 years ago that takes us back in time. Reflecting the rising postwar flight to the suburbs, Crestwood Station, a stop on the Harlem Line into New York, is crowded with well-dressed commuters. Notice how, in those days, hats were de rigueur out of doors — one exception being the housewife in curlers kissing her husband goodbye (bottom left). For a parallel to the modern commuter, notice the rapt attention each one has to their own newspaper — no socializing, no chatter. Today, of course, all that attention would be devoted to a phone.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell / SEPS

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Cartoons: Getting from Here to There

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

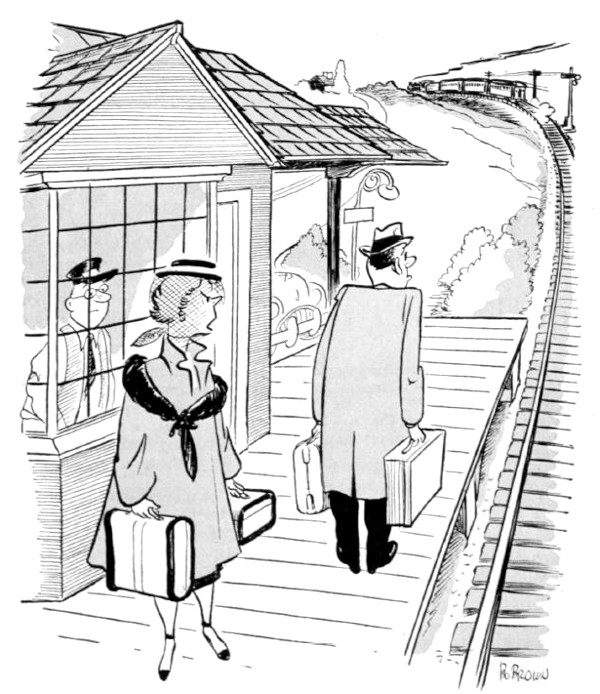

Bo Brown

June 30, 1951

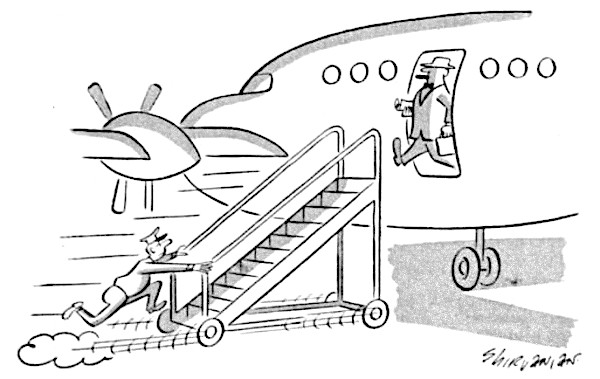

June 21, 1952

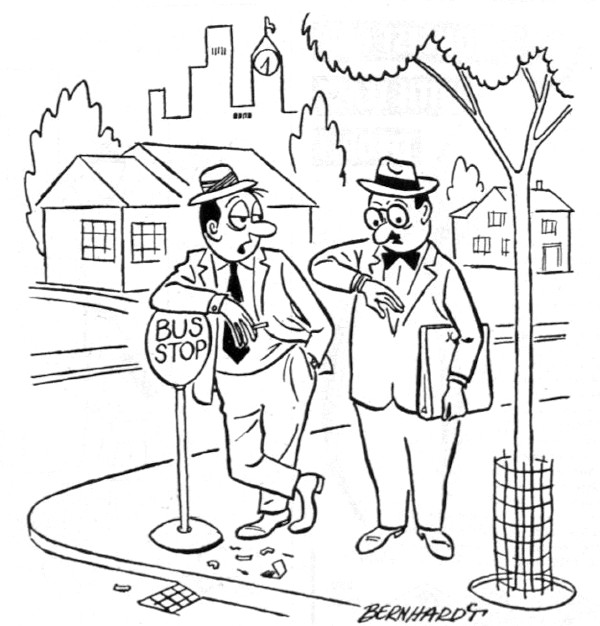

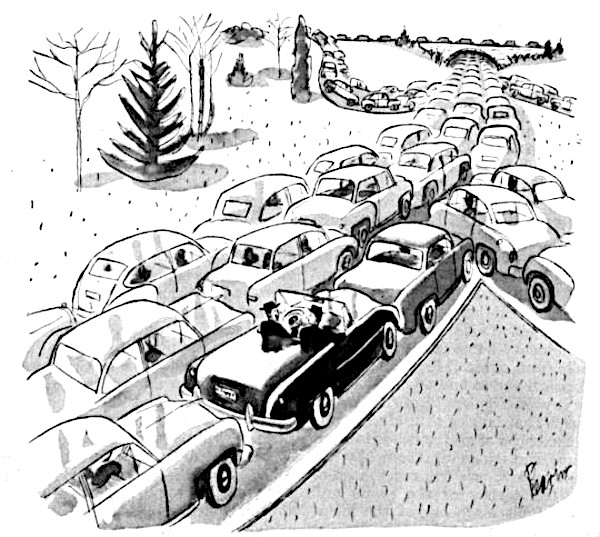

Bernhardt

May 19, 1951

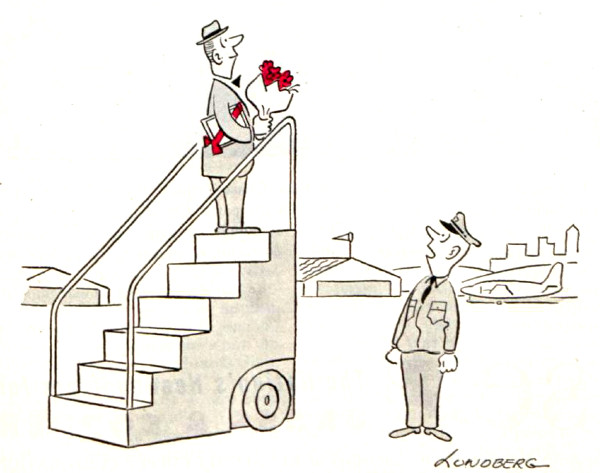

Lundberg

May 10, 1952

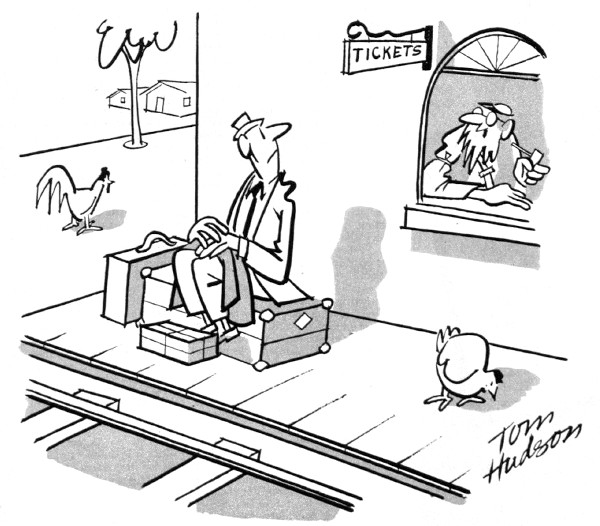

Tom Hudson

May 28, 1951

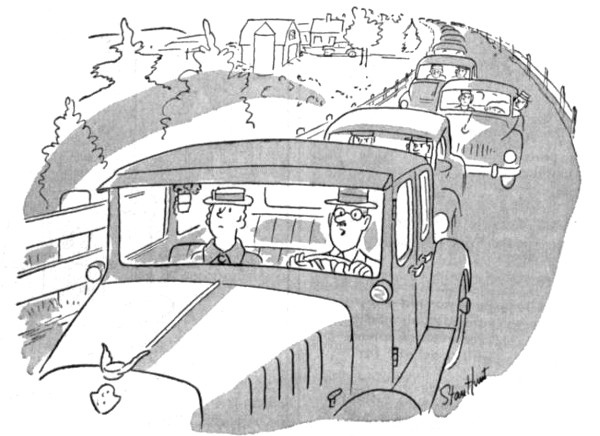

Stan Hunt

November 22, 1952

October 25, 1952

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

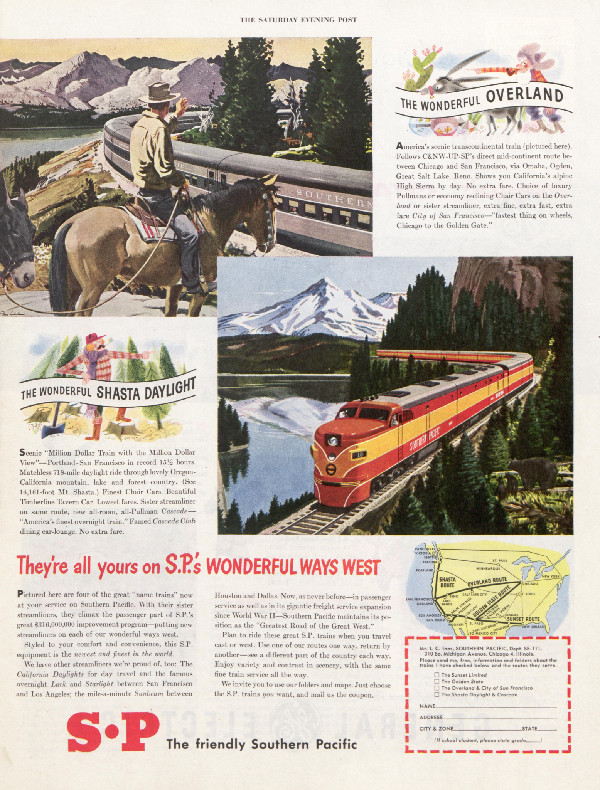

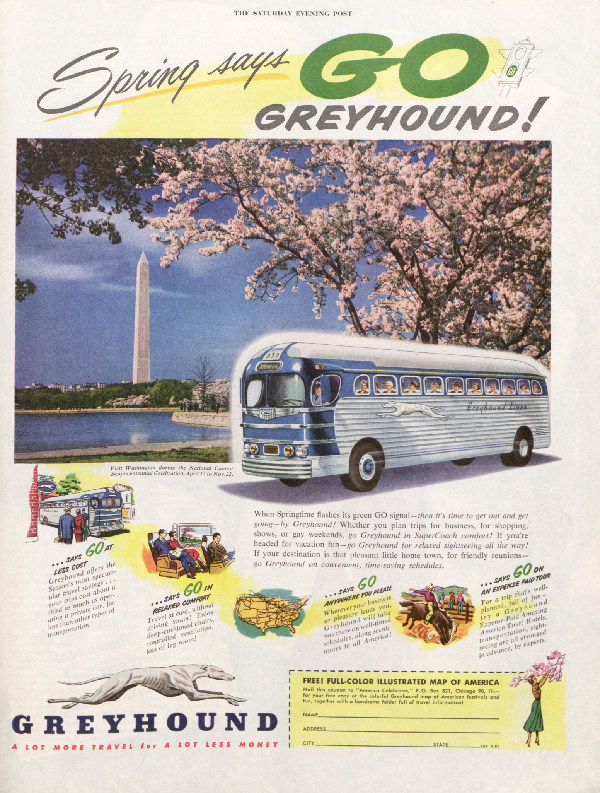

Vintage Ads: Travel in the 1950s

Want to look at all of our ads from the 1950s? Become a member! Members receive 6 issues of The Saturday Evening Post per year plus complete access to our online archive dating back to 1821.

March 3, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

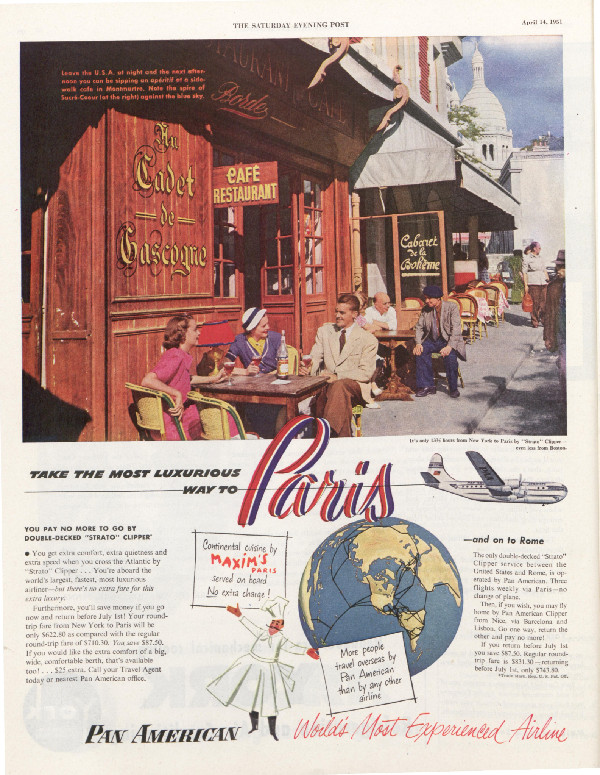

April 14, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

November 25, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

November 18, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

December 1, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

July 1, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

June 24, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

March 25, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

March 1, 1952

(Click to Enlarge)

October 6, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

Want to look at all of our ads from the 1950s? Become a member! Members receive 6 issues of The Saturday Evening Post per year plus complete access to our online archive dating back to 1821.

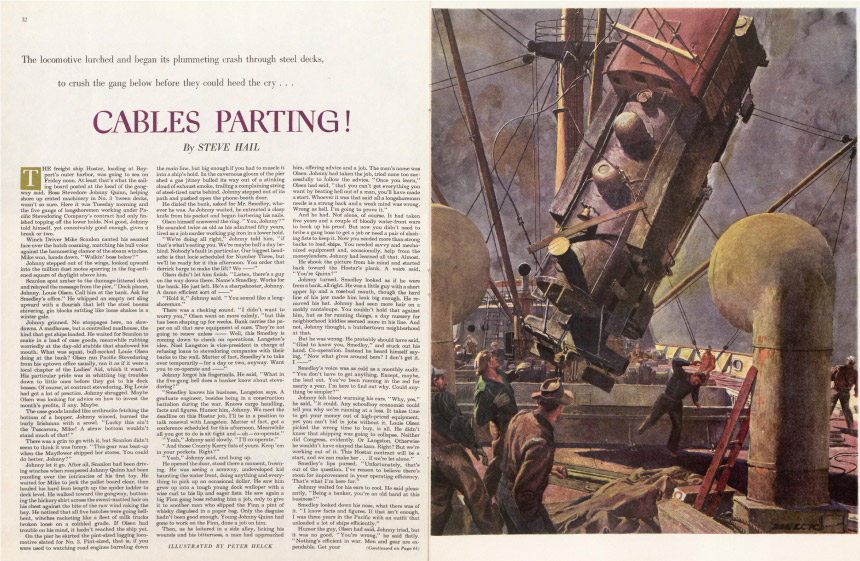

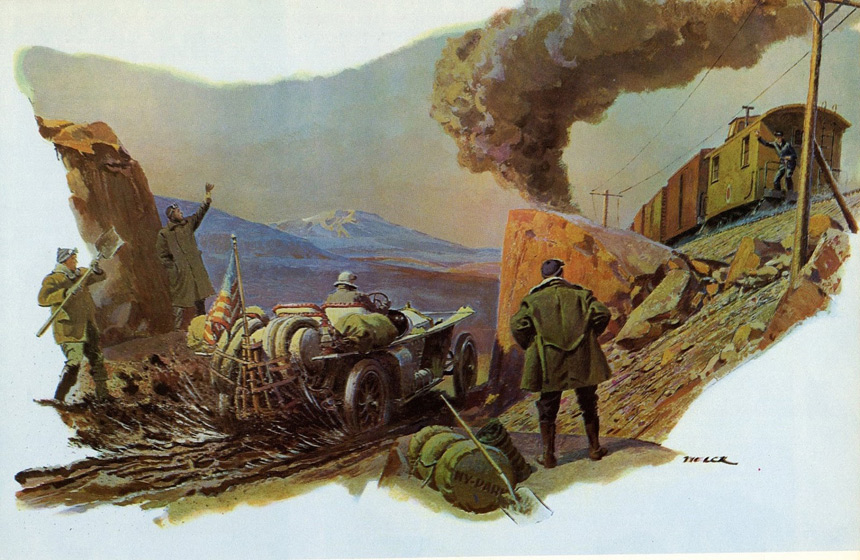

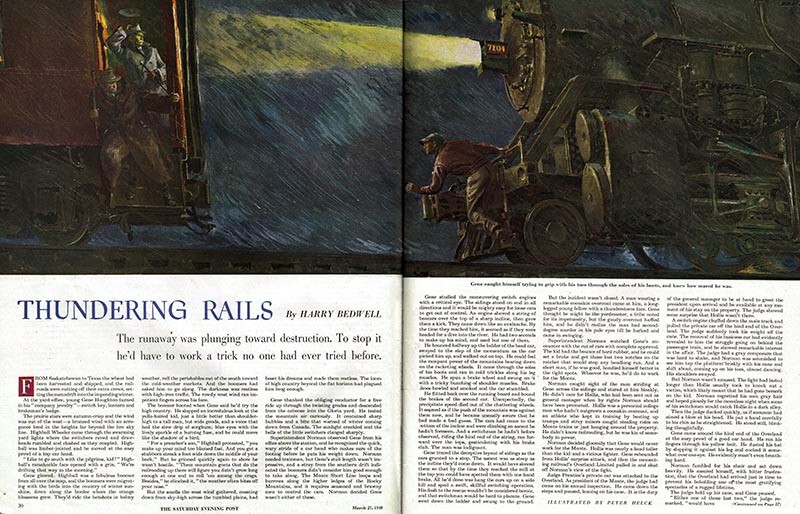

The Art of the Post: The Artist Who Loved Trains

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

Some artists specialize in painting landscapes. Some focus on painting portraits. Peter Helck painted trains.

Helck found as much excitement and inspiration in trains as other artists found in love stories. An article about Helck in American Artist magazine said, “he paints [railroads] with authenticity and with a dramatic power which expresses the romantic appeal these things have for him. He is passionately fond of locomotives; they are frequent subjects of his canvases.” Helck put it more bluntly: “[I’ve been] wacky over steam locomotives all my life.”

Helck was born in New York City in 1893. By the time he was 10 years old, he was spending his allowance each week on the model trains at Coney Island. His first art jobs were working for the art departments of local stores. As his reputation grew, he graduated to illustrating for magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post. Publishers spotted his special talent for painting machinery and industrial equipment, so when an assignment called for a picture of machines such as trains or old cars, Helck became the first artist they called.

At age 30, Helck moved to a large farm in Boston Corners, about 100 miles north of New York City. On his farm he had room to store his growing collection of battered old cars and tractors. When he wasn’t painting, he enjoyed working on them in his barn.

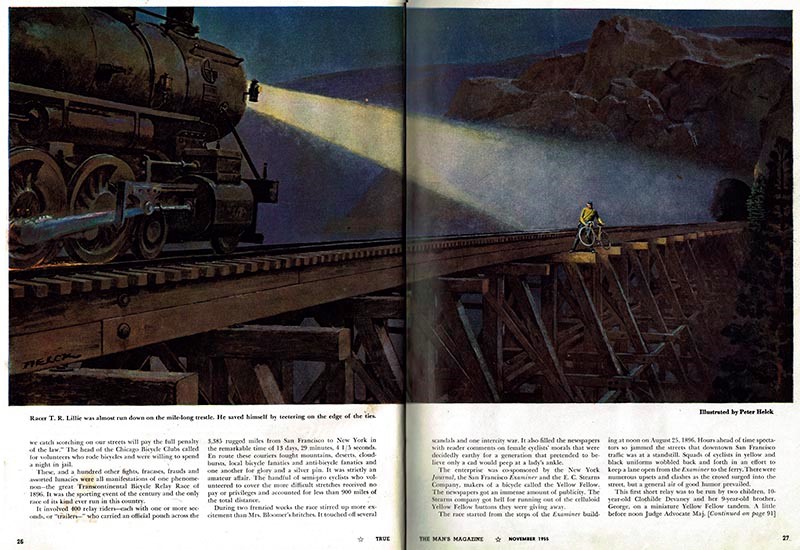

One of Helck’s favorite things about illustrating trains was that he occasionally wrangled permission to ride in the engine cab of real trains, sketching details and getting a sense for the experience. While illustrating the story “Thundering Rails” for the Post (March 27, 1948) Helck was able to ride in the engine cab of a train to Albany, New York.

He recalled breathlessly, “I got to work in an atmosphere gloriously dense with soot and smoke and generously affording the dramatic night lighting effects of which I never tire.” Of course, sometimes he forgot to ask permission. More than once he was kicked out of a train cab for trespassing.

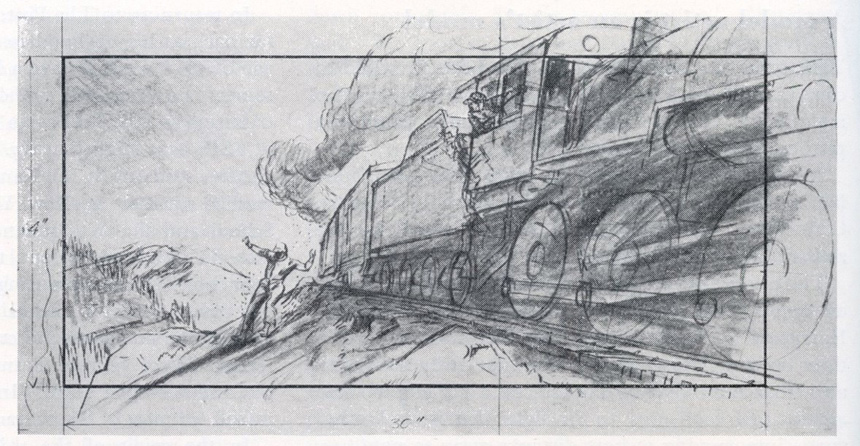

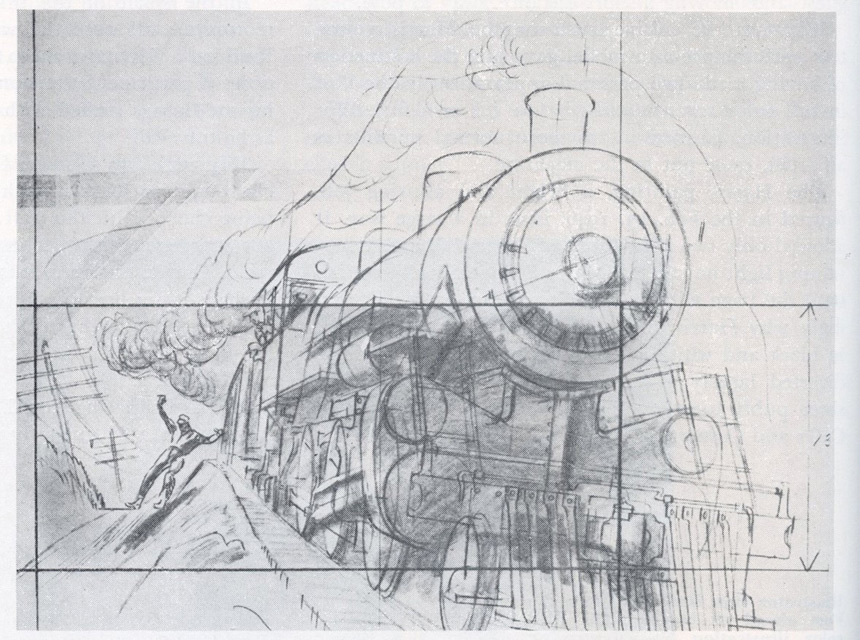

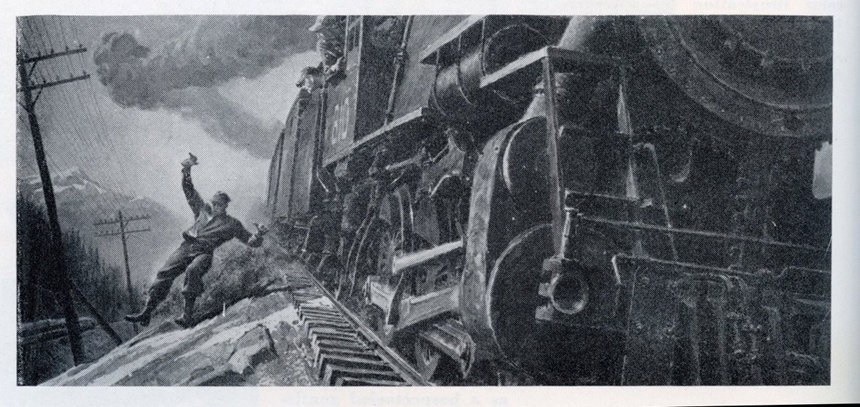

He also ran into trouble because he sometimes made the train, not the people, the star of his painting. As you can see from the following preliminary sketches for the story, “Screaming Wheels,” (The Saturday Evening Post, February 19, 1949) Helck started out by giving the starring role to the train, leaving a only a minor role for the human (who was supposed to be the center of the story).

In the next drawing, Helck was nudged into increasing the importance of the man jumping off the train. Still, the train remained too prominent, so you can see how Helck cropped his beloved train to diminish its role even further.

Here is the final version as it appeared in The Post, with the train veering off to the side and the man in the central role.

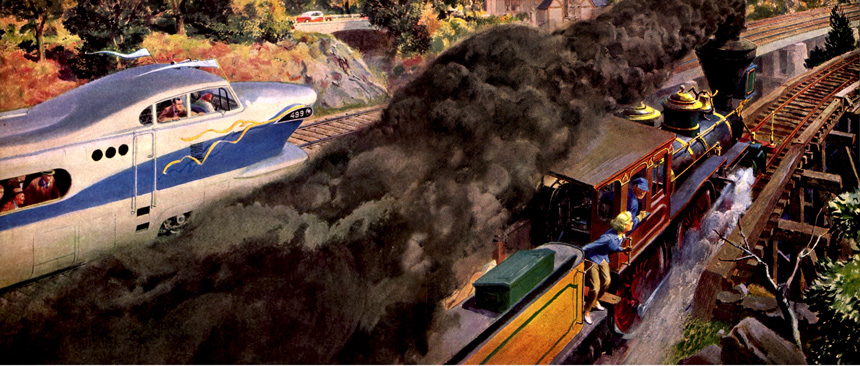

For another assignment, Helck painted a locomotive with smoke belching from the smokestack. When he delivered his finished painting, a junior account executive didn’t care for the dirty smoke, so he rejected the painting. He instructed Helck to take it back and paint a cleaner version minus all the smoke. However, when the art director saw the cleaner version, he was livid. He called Helck and asked him to restore the smoke, grumbling, “I was out of the office, sick, and that so-and-so went over my head. If I send it back will you put the guts in it again?”

Because Helck understood trains from top to bottom, he was even able to imagine how a falling locomotive would look. Obviously, no one could suspend a massive locomotive mid-air for Helck to paint, but he could project one in his mind. What other illustrator could pull off such a feat?

Most artistic traditions have been shaped over thousands of years. Artists in ancient Greece and Rome studied the human body and developed conventions that were passed down by artists through the ages. Renaissance painters made great strides in learning how to paint fabric and metal surfaces. Hundreds of generations have explored different approaches to painting the human face.

But trains were different. Trains were still relatively new when Helck was born, so he could not rely on generations of artistic solutions. Artists were still shaping the basic traditions for painting the speed, power, smoke, and other features of a locomotive. Helck’s love and enthusiasm for trains made him well suited for inventing and popularizing their images.