The Art of the Post: Painting the Human Circus

Few illustrators could paint the human circus the way Albert Dorne did.

Click to Enlarge.

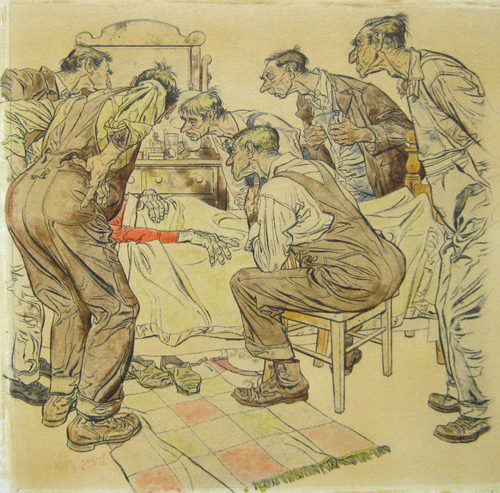

Click to Enlarge.

His illustrations were famous for their parades of colorful and scruffy people—geezers, yokels, oddballs, street urchins, con men, jilted lovers, and lowlifes.

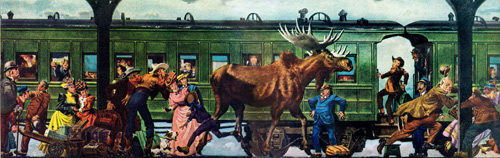

Click to Enlarge.

His sharp eyes noticed and captured a wealth of details—wrinkles, lumps, warts, patches, and folds.

Click to Enlarge.

He was a keen observer of human nature and entertained readers with a front row view of humanity that few had seen before.

How did he understand this world so intimately?

Dorne was born in 1904 in the slums of New York City. His father abandoned the family, leaving Dorne’s mother alone to feed Albert and his three siblings. Dorne’s childhood was wracked with the diseases of dire poverty and despair: anemia, malnutrition, heart ailments, and tuberculosis. More than once, city health officials intervened to remove Dorne from his home and place him in a city sanatorium. By the time he turned nine, the boy realized that he needed to take desperate measures if he was going to escape the slums. Public school seemed like a dead end, but he thought he might have a chance to bring in a little money by selling art.

Dorne began sneaking away from school and spending time in New York’s free museums where he could learn about making pictures. By age ten, Dorne was skipping school two or three days a week. He was frightened to death that the truant officer would find him and took elaborate steps to avoid being caught. His favorite hiding place was the Metropolitan Museum of Art; he later claimed to have taught himself by copying every piece of art in the museum (including the armor and the sculptures). Museum guards took a liking to their small visitor, and soon he became the youngest person ever to receive a permit to draw and paint in the galleries.

In the seventh grade, Dorne stopped going to classes altogether. He felt that as the eldest son, it was his responsibility to support his family. It later turned out that Dorne didn’t even need to hide from the truant officer. His teachers had caught on to what he was up to and agreed among themselves not to turn him in. They admired his pluck and believed his chances for a decent life were better at the museum than they were at school.

Dorne first found a job selling newspapers on street corners. Most paper boys picked corners with the heaviest traffic, but Dorne shrewdly calculated that if he sold papers in front of a fancy restaurant, he might have fewer customers, but he could still make more money because customers who just enjoyed a fine meal were more likely to be big tippers. His plan worked. Before he turned 12, he had staked out four other strategic locations and hired his friends to staff them.

While he worked as a newsboy, Dorne continued to look for more work. He sometimes held three jobs at once. He became a milkman’s helper, an office boy for a chain of movie theaters, a shipping clerk, a salesman, and a loading dock worker. He painted faces on porcelain dolls on a factory assembly line and when he turned sixteen he even became a prizefighter. (After all, Dorne reasoned, he had been involved in street fights with gangs while growing up in the ghetto and had done pretty well.) As a boxer, he won ten consecutive matches before he was knocked out cold by a tough professional fighter. Dorne quickly decided to give up boxing. But the characters he met during his struggle to the top would all come back as material for his illustrations.

Click to Enlarge.

Having taught himself to draw, he found a job illustrating sheet music. He was paid a total of four dollars for his first picture, but he continued to improve and soon he was earning $90 per week as a letterer. He took a full time job in a commercial art studio, drawing low-budget ads for an array of small time clients. This was a high volume business in the melting pot of New York City learning to satisfy clients whose language he often did not speak and whose culture he often did not understand. Dorne called this “hack work of every description,” but it sharpened his business instincts and taught him more about human nature. He worked around the clock doing as many as ten illustrations per day, which taught him to work quickly. He often slept on the floor in the studio.

Even after he became successful, he never stopped hustling for new business. Eventually, Dorne became the wealthiest illustrator in America, the president of the Society of Illustrators, and the founder of the international Famous Artists School. He drove a custom made Mercedes with a burled walnut dashboard and a pull-out bar. His steering wheel featured a silver plaque with Dorne’s initials and a large star sapphire.

When Dorne died in 1965, a friend remarked, “he painted pictures as if the truant officer were chasing him, and he never stopped.”