The Softer Side of Ty Cobb

On July 18, 1927, Ty Cobb became the first baseball player to reach 4,000 hits. Ninety years later, Ty Cobb still holds many records. He also holds onto the reputation of being one mean ballplayer.

Tyrus R. Cobb certainly had a quick temper and was an aggressive athlete. He was argumentative and often engaged in fist fights. But there’s no proof for the stories about him beating up a handicapped man, or of sharpening his spikes so he could sink them into the shins of any opponent who blocked his slide into base.

Many of these stories were fabricated by journalists who knew they could attribute any outrageous actions to Cobb and people would believe them.

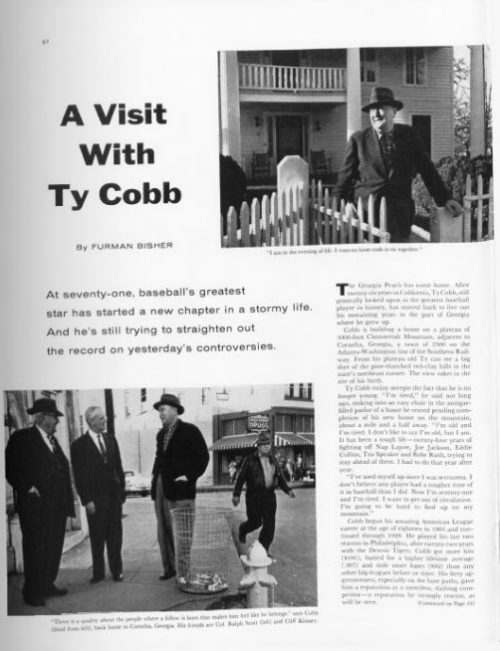

So Post readers familiar with the notorious Cobb would have been surprised to read about the sentimental, soft-hearted philanthropist described in the June 14, 1958, article, “A Visit with Ty Cobb.”

In 1956, Cobb donated $100,000 (worth nearly nine times that amount today) to build a hospital for his small home town. He also established the Ty Cobb Educational Foundation with another $100,000. By 2016, this college fund had disbursed over $16 million to disadvantaged students and is still in operation.

Cobb’s generosity was not a consequence of a large salary. In all his years as a ballplayer, he never earned more than $40,000 a year, even at the height of his 23-year career.

Surprisingly, when he retired in 1928, he was a rich man. During his ball-playing years, he had been wisely investing in rising companies like General Motors and Coca-Cola. When he died, he left an estate worth, in current dollars, over $90 million.

Author Furman Bisher was intent on writing a positive story, which is why he skipped over some unpleasant parts of Cobb’s past. For example, he writes that Herschel Cobb, Ty’s father, “came to an early death at 43 — the victim of an accidental shooting.” What he doesn’t mention is that the shooter was Ty’s mother, who was tried for murder and acquitted.

That story is true.

Featured image: Ty Cobb, 1913 (Library of Congress)

Ty Cobb’s Secret Admirer

This article and other features about baseball can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, Baseball: The Glory Years. This edition can be ordered here.

In the summer of 1904, the youthful sports editor of the Atlanta Journal began receiving an interminable series of telegrams from some anonymous correspondent in Anniston, Alabama, about a local ballplayer named Ty Cobb.

“Cobb clouted a home run and two singles this afternoon — a real comer … ” “Big gun in Anniston attack was Cobb …” “Although hitless, Cobb stole two bases today …” “Cobb, Cobb, Cobb … ”

The sports editor kept throwing these wires in the wastebasket, but finally his resistance broke down. He hopped a train to Anniston, to judge for himself whether this busher really was, by any chance, a phenomenon in the rough.

What he saw convinced him completely. The young Anniston out elder collected five hits in five times at bat, and stole home to assure his team victory. The sports editor headed for the local telegraph office, and put himself on record with a 300-word dispatch to his paper:

“Ty Cobb was a comet with a fiery tail this afternoon. He blazed the Annistons to victory with his booming bat and his fleet base running. Here is a young man who someday may make his mark in the baseball world … ”

This story, ironically, never got into the paper. The sports editor’s assistant, thinking it was just another outburst from Cobb’s unknown Boswell, killed it when it reached the Atlanta Journal office.

However, with the sports editor now sold to the hilt on Cobb, the wires from Anniston began breaking into print with regularity. Cobb’s fame spread through Dixie. Augusta, which had previously discarded Cobb, signed him up again. Late in the 1905 season he moved up to Detroit and, of course, went on to establish himself as the mightiest ballplayer of them all.

The youthful sports editor also reached the heights. He still looks back with pride on his early discovery of Cobb. Today he is the dean of all sports writers, Grantland Rice.

As for Cobb, he remembers those brief 1904 items more vividly than any of the long screeds which have been written about him since. He should. The anonymous Anniston correspondent who sent them in was Cobb himself.

— “Cobb’s Progress” by Ernie Harwell, Sept. 12, 1942