A Brief History of the Minimum Wage

Recently, CBS News observed that it’s been 11 years since the last federal minimum wage increase, while in the same time period, the cost of living has risen 20 percent, squeezing low-wage workers who are already struggling during the pandemic. We took a look at the history of the minimum wage, controversies surrounding it, and the chances that Washington will raise it anytime soon.

Over 120 bills were sitting President Franklin Roosevelt’s desk on June 25, 1938, waiting for his signature. Somewhere in that stack was a bill that would have a huge impact on American labor. Called the Fair Labor Standards Act, it would, at first, only apply to businesses engaged in interstate commerce, and affect only 20 percent of America’s work force. But it outlawed child labor, set a maximum of 44 hours for a work week, and it guaranteed a minimum wage.

A similar law had been struck down by the Supreme Court in 1935. But the Court reversed itself two years later, and a new bill was sent through Congress. It met opposition from small manufacturers who declared they couldn’t afford to pay their workers the 40¢ an hour wage the law would require. Roosevelt compromised, setting the minimum hourly wage at 25¢ for the first year.

By this time in his administration, Roosevelt was accustomed to the cries of outrage from his opponents. The night before he signed the bill, he told Americans in one of his fireside chats, “”Do not let any calamity-howling executive with an income of $1,000 a day…tell you…that a wage of $11 a week is going to have a disastrous effect on all American industry.”

The following year, the minimum wage was hiked a nickel, to 30¢ an hour. The next raise came in 1945, when inflation followed the increased money supply circulating in the wartime economy. The wage rose to 40¢ an hour.

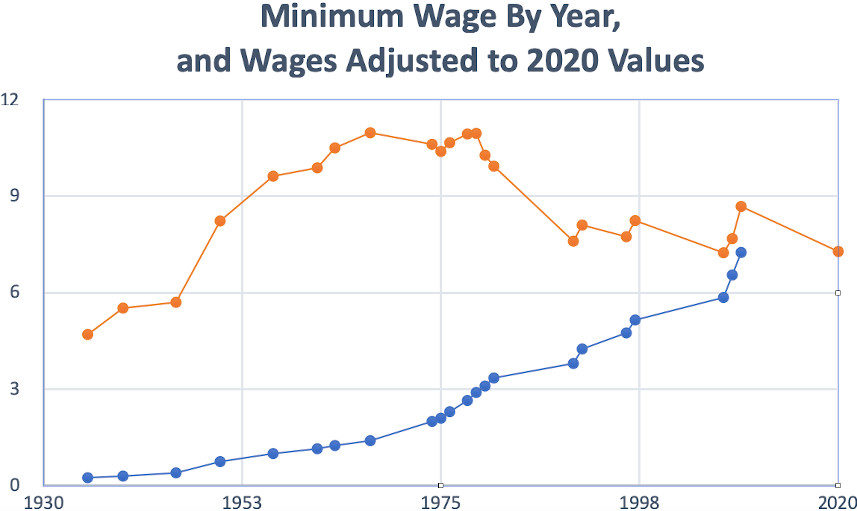

Over the years, the wage level has been lifted to reflect inflation and the rising cost of living. But successive congresses had differing ideas about what a minimum wage should do. Inaction led to the minimum wage often failing to keep pace with inflation, as shown below.

The lower line shows the actual hourly wage over the years. The upper line shown the value of that wage in 2020 dollars. Thus, the purchasing power of the 25¢ earned in an hour’s work in 1938 would be worth $4.70 today.

The highest minimum wage, when you adjust for inflation, was set in 1979, when it reached a value equivalent to $10.95 an hour today. Though increased several times, its relative value has gradually declined in the subsequent 41 years.

Today, a worker earning the federal minimum wage receives $7.28 an hour, before taxes. That wage was established back in 2009, and has set a record for the longest time without a raise. In the 11 years since then, the wage has lost 17 percent of its purchasing power.

Don’t confuse “minimum wage” with a “living wage” — the amount necessary to cover basic living expenses. Professor Amy Glasmeier of MIT has calculated a living wage based on estimated basic costs of food, child care, health care, housing, transportation, and other necessities, and compares it to the local minimum wage and poverty wage.

Poverty wage is lower than the minimum wage. A single person earning less than $12,760 is considered living in poverty. For a family of four, the figure is $26,200.

The poverty line was first calculated in 1955 by determining food expenses took up a third of a family’s budget after taxes. Therefore, the Agriculture Department multiplied food costs by three. The same calculation is used today, though the cost of food is continually adjusted in accordance with the Consumer Price Index.

The poverty wage determination is based on basic living. It doesn’t factor in varying housing or transportation costs. It doesn’t allow for leisure, entertainment, or food outside the Agriculture Department’s regimen of inexpensive meals. It means strict subsistence and no opportunity to save money.

For the average family of two adults and two children in the United States, the living wage is $16.54 per hour, or $68,808 a year. In contrast, the average minimum wage worker earns $15,080 a year.

If you hope to earn the living wage for a family of four, you would need to work almost four full-time jobs. At minimum wage, a single mother of two children would need to work nearly 24 hours a day for six days a week.

According to federal guidelines, two people with a total annual income below $16,910 are legally poor. The New York Times calculated that at least one person would need to earn a minimum of $8.12 an hour to escape the impoverished designation.

Since Washington can’t agree to raise the minimum, many states have stepped in to establish their own. As of 2018, 29 states, including Washington, D.C., have established minimum wages higher than the federal level. For example, Oregon, Washington, and Florida, which adjust their minimum wages to reflect rises in the consumer price index, pay workers between $9.00 and $11.00 an hour.

In addition, some cities have raised their minimum wage even higher. In Seattle, it will be $15.45 per hour next year. Not long ago, San Francisco raised its minimum to $15 per hour, which boosted the salaries of nearly a fourth of the city’s workforce.

There have been repeated efforts to raise the federal minimum wage. Proponents have argued that the current rate does little to help workers. Opponents claim that raising wages would lead to an increase in consumer prices and lay-offs of some workers to pay the higher wages of others. Economists have reported research that both supports and contradicts the various claims.

In 2019, when the House of Representatives passed a bill to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, the Congressional Budget Office predicted the law would increase the wages of 17 million workers, but put another 1.3 million out of work. The Center for Economic and Policy Research, on the other hand, found little or no change in employment resulting from modest increases in the wage.

One benefit to raising the minimum wage could be increased spending among lower income workers, leading to a higher demand for goods. (This was Henry Ford’s thinking when he raised his minimum wage to a record-breaking $5 a day. “The owner, the employees, and the buying public are all one and the same,” he wrote, “and unless an industry can… keep wages high and prices low, it destroys itself, for otherwise it limits the number of its customers.”)

Another unexpected effect of raising the minimum wage could be the reduction in government spending. According to a UC Berkeley study, over half of fast-food workers rely on public assistance checks to get by. Just raising the minimum wage to $10.10 would eliminate $7.6 Billion in income-support programs.

The prospects for increasing the minimum wage don’t appear good. In the current economic climate, with 10 percent unemployment, the supply of labor exceeds the demand. Workers have little leverage over employers. Businesses, particularly those operating on margins made razor-thin by the recession, will have small motive to increase pay.

A further obstacle is indicated by a recent study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which found employers often respond to minimum-wage hikes by bringing automation in to take the place of human workers.

The good news, though, is that fewer and fewer Americans are limited to living on that income. In 1980, 17 percent of workers were receiving minimum wage. In 2018, that percentage had dropped to just only 2 percent.

Featured image: Hyejin Kang / Shutterstock