Where the Civil War was Won

This is the fourth installment of our six-part series on the Battle of Gettysburg. To recap: In part one, “The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move,” we described how the Post reported the initial news of the invasion. In part two, “Scrambling for Soldiers,” we looked at the renewed attention to the draft. And in part three, “Americans United to Support the Civil War Troops,” we covered a special organization of volunteers who helped save thousands of soldiers’ lives.

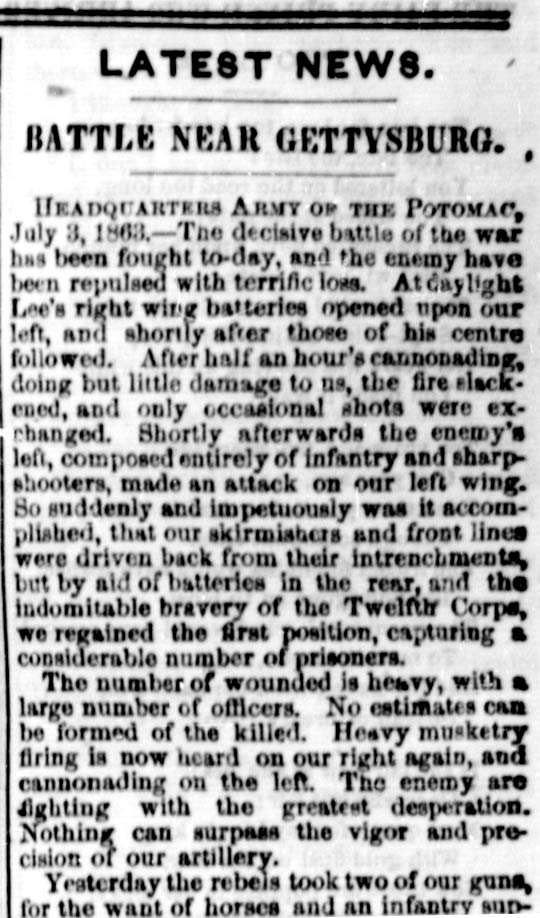

Unfortunately, the Post didn’t have regular reports from correspondents in the field like the major newspapers. So the editors provided bulletins taken from military dispatches telegraphed to Washington, D.C., which were inserted just before the paper went to press. For example, the July 1863 issue included this update:

HARRISBURG, June 28, P.M.—The capital of the state is in danger. The enemy is within four miles of our works and advancing. The cannonading has been distinctly heard for three hours. … Rebels have occupied successively [nine towns] and are now spread over all the region lying between the Susquehanna and Laurel Ridge. Not a single point in that whole section remains in our possession.

Some of the Post’s war coverage reflects the values peculiar of those times. While modern readers might want to know more about the experiences of the fighting men, the Post editors felt it was important to report how many cannons and flags were lost in battle. They also gave much coverage to the cavalry, which was assumed to be essential to an army’s success. A Post writer observed, “On a field of warfare where the distances are so great, the cavalry arm of the service is not only useful but absolutely indispensable.” At Gettysburg, we now know, the cavalry played a minor role, which barely affected the outcome of the battle. The battle was won by the men of the Union infantry and artillery who withstood massive Confederate assaults all along the Union lines.

In hindsight it’s interesting to note that the Post gave slight coverage to what would become one of the most memorable events of the Civil War. Shortly after the shooting had stopped on the battlefield, a correspondent filed this report:

HEADQUARTERS, ARMY OF POTOMAC, JULY 3—At daylight, Lee’s right wing batteries opened upon our left, and shortly after those of his centre followed. After half an hour’s cannonading, doing but little damage to us, the fire slackened, and only occasional shots were exchanged. Shortly afterwards, the enemy’s center, composed entirely of infantry and sharpshooters, made an attack on our left wing. So suddenly and impetuously was it accomplished, that our skirmishers and front lines were driven back from their entrenchments …

With these few words, the reporter covered what would become one of the most famous events of the battle: the attack on Cemetery Ridge by three Confederate Generals: Maj. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble, Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew, and Maj. Gen. George Pickett.

Pickett’s Charge, as it came to be known, began on the afternoon of July 3, 1863, when 13,000 rebel soldiers emerged from the woods west of Emmitsburg Road. They formed themselves into two lines of battle more than 1 mile wide and marched, not charged, straight toward the waiting Yankee line. Before them lay 1,400 yards of open fields that rose gradually to a ridge where the Union infantry and artillery had an unobstructed line of fire. The Confederates tried to hold their formation, but the line became disjointed as the soldiers had to climb fences to proceed. And, as the Union cannon fire began, great holes appeared in the line. The gaps grew wider as the rebels came within range of the Union muskets. Before the Confederates reached the crest of the ridge, half of their number had been killed or wounded. Yet the rebels continued on with a relentless, steady pace until, within yards, they finally broke into a charge. They slammed into the Union line and began a fighting hand-to-hand struggle with the Yankee defenders. For a few minutes, the outcome of the battle and, some say, of the war, hung in the balance as Northern and Southern soldiers crowded at the breached Union line.

For the Confederates, a breakthrough here would cut the Union Army in two, a victory that would culminate two years of fighting in which the Union had not won a single, definitive victory against Lee’s men. Lee wanted this victory, not just to clear the way for marching into Baltimore or Washington, D.C., but to destroy the North’s morale.

For the Union, however, this was not just another battle. The Federals had seen two years of fighting in a long, frustrated struggle to seize the Confederate capitol at Richmond, Virginia. They were well acquainted with defeat; General Lee had defeated them so often that many were starting to believe he was invincible. Now, here was Lee in the North with the 70,000 men of his formidable Army of Northern Virginia.

The Union soldiers knew that the outcome of this fight would decide the fate of their army and their country. On Wednesday and Thursday, they had fought with growing desperation as the rebel army broke through their defenses three times. Each time, Union reserves appeared at the last minute to hold the line. Yet each save had extracted a heavy cost. The divisions on the right and left of the Union line probably wouldn’t withstand one more attack. Fortunately for the Union, on the third day, the rebels had chosen to attack the center of the line.

And so, sometime around 3:30 p.m. on July 3, 1863, a crowd of gray uniforms spilled over the low stone wall on Cemetery Ridge. The Union soldiers gathered to push them back. Soon there was a dense crowd at the wall fighting hand-to-hand, the men were packed so tightly that many of the soldiers couldn’t even use their rifles as clubs.

And then—

… by aid of batteries in the rear, and the indomitable bravery of the Twelfth Corps, we regained the first position, capturing a considerable number of prisoners.

The Post’s correspondent didn’t recognize the history held within that paragraph of news, but he was surprisingly farsighted in his judgment. Because even with the rebel army still on the field, with both armies exhausted and no one quite certain that Lee wouldn’t try another attack, he felt confident to write the enemy had been repulsed in—as he called it—“the decisive battle of the war.”

Coming Next: Little Women in a Military Hospital