The First Vaccination Scandal

Vaccination has always been a divisive issue. As early as 1821, public reaction against inoculation caused the federal government to close down a vaccine program to prevent smallpox.

In its time, smallpox was one of the most fearful illnesses that could strike humans. It could cover a patient’s body in pustules in just 24 hours. If patients were lucky, they suffered for only two to three weeks and were left with depigmented skin and disfiguring scars. The unlucky ones — 30–50 percent of patients — died.

One of the first advocates of inoculation was the influential minister Cotton Mather, who learned about it from his slave Onesimus. He began promoting the idea to New Englanders, and it was largely through his efforts that the 1721 smallpox epidemic in Boston was contained.

But the idea ran into strong resistance. First, there was the vaccine itself. It was made from the serum of cows infected with cowpox that, when injected into healthy people, rendered them immune to smallpox. But people were understandably reluctant to introduce substances from diseased animals into their systems.

Secondly, many American clerics of the early republic denounced inoculation, claiming that it interfered with the Divine will. It might give immunity to sinners whom God was planning to smite as punishment. Cotton Mather received death threats for thwarting the will of God, one critic even attempting to blow up his house.

Lastly, there were the objections of merchants. Worrying that any talk of smallpox would hurt business, they downplayed or dismissed any news of smallpox cases. But in 1777, there was no denying that smallpox was killing the revolutionary army faster than the British. John Adams reported ten soldiers were killed by disease for every one killed in battle. That winter, Washington ordered a mass inoculation of his army.

As a result, the Continental army could remain in the field instead of field hospitals. President James Monroe was reminded of that success in 1813 when smallpox outbreaks began recurring. In response he signed “An Act to Encourage Vaccination.” It established the United States Vaccine Agency “to preserve supplies of genuine vaccine matter and furnish the same to any citizen of the United States.”

Dr. James Smith accepted the position as its director, a decision he might have later regretted. He was given no staff and no funding, and he faced opposition from state governments, which claimed the constitution gave no authority over public health issues to the federal government. Other doctors protested Smith’s agency because it allowed non-physicians to perform vaccination without the hefty fees doctors charged.

And then came the Tarboro Scandal.

In 1821, Dr. John Ward, an “auxiliary vaccine agent” in North Carolina, noted a rising number of smallpox cases in the area around Tarboro. He asked Smith for a supply of vaccines, and Smith promptly responded. But he accidentally sent samples of the smallpox virus. When they arrived, Ward didn’t read the label that would have warned him he’d received the wrong materials. He began inoculating area residents with live smallpox. By late winter, 60 people had contracted smallpox and ten had died.

Dr. Ward shifted all the blame onto Dr. Smith, and his accusations were taken up by Congressman Hutchins Burton of North Carolina. Burton proclaimed that the Vaccine Agency and Dr. Smith had, through indifference, “slaughtered citizens of North Carolina.” He also claimed, falsely, that Smith had also introduced smallpox to the interior of the nation when, previously, it had been confined to coastal cities.

A Congressional investigation into the matter confirmed the mistake, but also exonerated Dr. Smith and praised his agency’s work. Congressman Burton had planned to make political capital on a critical report. So he demanded another committee and this time had himself appointed to it. He wrote its final report, which was, not surprisingly, extremely critical.

Now rumors began circulating that Dr. Smith had been somehow profiting from the vaccine’s use, and was even spreading smallpox on purpose.

Burton had two reasons for attacking Smith. He wanted to show his constituents that he was representing their anger in Washington. But there was also a political reason. Burton, like many anti-Democrats of the period, jealously guarded state sovereignty against perceived federal intrusion. Public health programs should be carried out by state officials, he believed. In the hands of the federal government, these programs led to despotic power

Sensing a “violent prejudice” against Dr. Smith, President Madison removed him from his position.

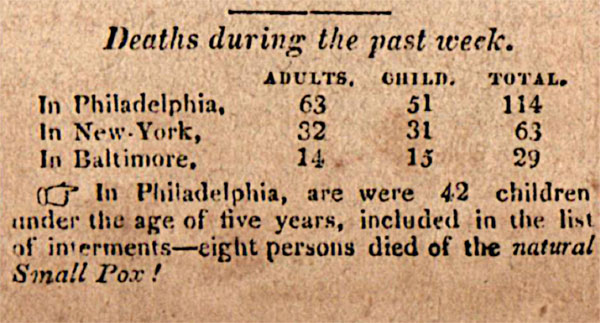

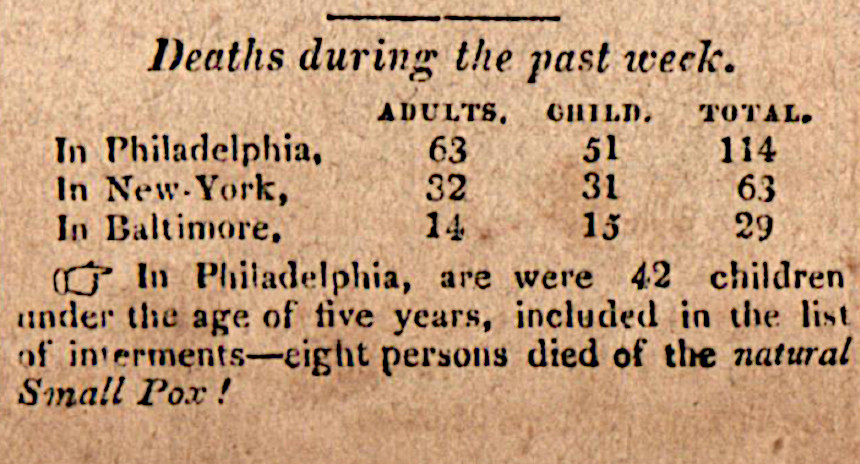

Smith fought to save his reputation. He launched a promotional campaign, publishing pro-vaccination papers and promising to supply vaccines at his own expense. But public resentment proved stronger than his reasons. The outcome was reported in the Saturday Evening Post on April 27, 1822:

In the House of Representatives of the United States, on Tuesday last, the Bill for abolishing the Vaccine Agency was under consideration, and after considerable debate, carried — Ayes 102 — Nays 57.

Epidemics of smallpox were eventually joined by outbreaks of cholera, diphtheria, measles, typhus, anthrax, and yellow fever.

But the federal government avoided any vaccination programs for the rest of the century.

Featured image: Caricature of vaccination scene at the Smallpox and Inoculation Hospital at St. Pancras, showing Dr. Jenner vaccinating frightened young woman, and cows emerging from different parts of people’s bodies (Library of Congress)

The Post Reports on Vaccines

Recent measles outbreaks have brought renewed media attention to and public discussion over vaccination. While the scientific community supports vaccination, some parents have rejected vaccinations for their children.

Yet vaccination has been a part of healthcare since the early 1800s, and The Saturday Evening Post has been reporting on them since the inception of the magazine.

The first Post mention of a vaccine was April 27, 1822, where the magazine noted the repeal of the Vaccine Act of 1813, the first federal law over consumer protection and pharmaceuticals. The act encouraged public vaccination against smallpox but was repealed in order to give the power of regulation to the states, where it has remained since.

A year later, in the November 29, 1823, issue, in a line item warned: “Small pox, it is feared, will prove fatal to many persons in Yarborough, N.C. owing to the use of matter not genuine, which had been forwarded to Dr. Ward by Dr. Smith, the United States’ Agent for vaccination.”

Concerns about the smallpox vaccine’s purity, efficacy, and authenticity persisted. People feared the vaccine would produce a “harmful disease” or “other diseases than vaccinia,” or “that compulsory vaccination is a trespass upon the inherent rights of the individual.” The earliest vaccine protesters believed that “the reduction in smallpox mortality in civilized countries to the generally improved sanitary conditions.” They did not associate lower rates of disease with higher vaccination levels as we do today.

Despite concerns, the smallpox vaccination grew widely. In the early 1800s, the vaccination was mandatory for infants in certain states, but deaths still occurred.

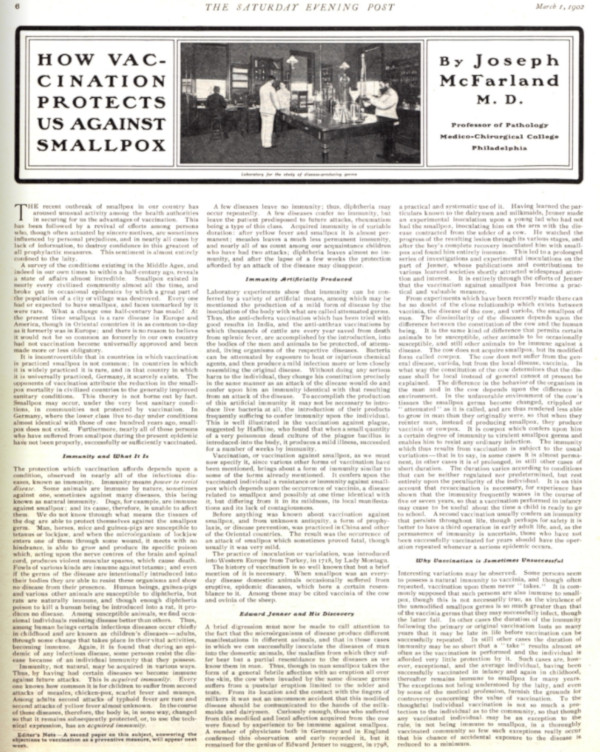

On March 1, 1902, an article titled How Vaccination Protects Us Against Small Pox, written by Joseph McFarland M.D., claimed “To the thoughtful individual vaccination is not so much a protection to the individual as to the community.” Due to their ability to prevent smallpox, the doctor believed the vaccine to be the “greatest of all prophylactic measures” and a great aid to American well-being.

As the years passed, protesters of the smallpox vaccine diminished along with the disease it prevented. Americans put their faith in inoculation and spread the process to other countries. When discussing vaccinating infants against smallpox, typhoid, and diphtheria in a May 16, 1936, article titled The New Machine, the magazine claimed “It may seem to many people that it is cruelty or dangerous to subject a little, delicate organism to the onslaught of these vaccines, but it is far more dangerous to let them go without it.”

Then there was the story of polio.

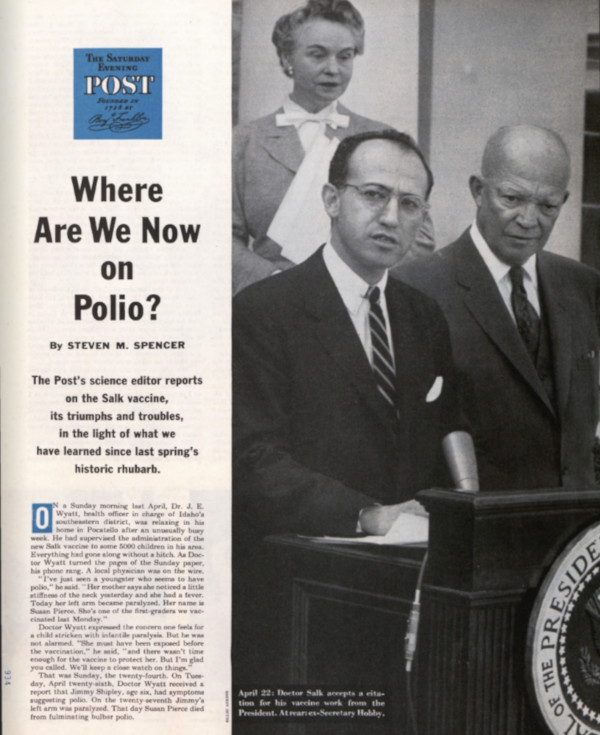

In April of 1955, Dr. Jonas Salk accepted a citation for his vaccine work from President Eisenhower. The new polio vaccine was a beacon of hope in fighting a deadly and terrifying illness. Polio cases in the U.S. fell from 35,000 in 1953 to 5,600 just four years later. In 1955, more than 8 million children had received the vaccine. By 1961, there were only 161 cases.

But the rollout of the vaccine was not without its problems. In the spring of 1955, several children contracted polio a week after receiving the vaccine, and some died. A panel of experts was convened in Washington, where they issued conflicting advice. Some wanted to temporarily halt the program. Others urged that it should move forward. Worried parents didn’t know what to do, and vaccination rates dropped.

Basil O’Connor, the president of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, was eager to see the program continue. He had seen too many children paralyzed or killed by the disease. At the hearing in Washington, he pointed out, “Since the scientific method was established, every important advance in science has met with the twin obstacles —ignorance and envy.”

But no one intended to do away with the polio vaccine. Research efforts continued, and a safer version the vaccine was developed in 1961. Polio was completely eliminated in the U.S. in 1979.

Throughout the century the vaccine saved thousands of lives and prevented countless outbreaks. By 1964 scientists were even wondering if they could vaccinate against cancer.

So why do concerns about vaccinations persist?

After the eradication of small pox and polio and the subsequent reduction of measles, a generation of parents who had never experienced these diseases began to question why their children should be vaccinated.

A now discredited study released in 1998 claimed relationship between vaccines and autism, quickly becoming a topic of great discussion in the United States. The journal retracted the study, but it was too late. Goaded by internet forums and a few strident celebrities, many concerned parents took a stance against vaccination.

Theirs was a movement that had existed in some part since the advent of vaccines. Vigorous protests have led to exemptions to the required vaccinations. While all state laws have “no shots no school” policies that prevent unvaccinated children from attending public schools, there are various exemption practices by state. All states allow medical exemptions for children to whom the vaccine could be harmful, and all but six states (California, Minnesota, Mississippi, West Virginia, New York, and Maine as of June, 2019) allow exemptions on religious grounds. Many states have also included a philosophical exemption for parents who protest vaccination for non-religious reasons. All exemptions can be revoked “during a public health emergency or outbreak of a communicable disease,” such as the recent measles outbreak.

Despite regularly making headlines, the anti-vaccination contingent remains in the far minority of the population. A CDC report published in 2018 revealed that the median percentage of kindergarteners with an exemption from one or more required vaccination was 2.2 percent. The “median percentage of nonmedical exemptions” was 2 percent. Most Americans support vaccination and the preventative power it holds. The vaccine’s long history in this country has saved countless lives and has turned public perception from doubtful to hopeful.

Featured image: At a McLean, VA, school, nurses Lillian Peyton and Mrs. John Lucas help Dr. Richard Mulvaney give Barbara Ann Schmitt a Salk polio vaccination (Photo by Ollie Atkins for the September 11, 1954, issue of The Saturday Evening Post)